Learning Outcomes

After completing this chapter, you will be able to

Define compounding.

Define compounding.

Describe the steps involved in the compounding process.

Describe the steps involved in the compounding process.

Describe the equipment commonly used when compounding preparations.

Describe the equipment commonly used when compounding preparations.

Identify the types of preparations commonly compounded.

Identify the types of preparations commonly compounded.

Explain the concept of and reasons for repackaging medications.

Explain the concept of and reasons for repackaging medications.

Explain the importance of record keeping for compounding and repackaging.

Explain the importance of record keeping for compounding and repackaging.

Key Terms

| active ingredient | Ingredient in the compounded preparation that is responsible for the therapeutic or pharmaceutical action of the medication. |

| batch record (or batch log) | The compounding record for a batch, usually filed by lot number. |

| batch repackaging | The periodic repackaging of large quantities of medications in unit-dose or single-unit packages. |

| beyond-use labeling | A date that is given to a medication noting when it should no longer be used, also referred to as the expiration date. |

| blister packages | Often called “bubble packs.” Composed of a plastic bubble that forms a cavity for the medication. The package is then sealed with a backing material that also acts as a label. |

| compounding | Usually takes place in a pharmacy and includes the preparation, mixing, packaging, and labeling of a small quantity of a drug based on a practitioner’s prescription or medication order for a specific patient. |

| compounding environment | Includes the facilities (i.e., compounding area) and equipment in the pharmacy. |

| compounding record | The log or record of an actual compounded preparation or batch that was prepared. |

| extemporaneous repackaging | Repackaging quantities of medications that will be used within a short period of time. |

| formulation record | An individual record (like a recipe) for a preparation. It includes a listing of the ingredients, compounding equipment, and instructions for preparing the compound. A formulation record may also be referred to as a formula or master formula. |

| geometric dilution | Compounding technique used to ensure the uniform mixing when there is a wide discrepancy in amounts of individual ingredients. The preparer starts with the smallest ingredient amount and mixes it with an equal amount (estimated by sight) of the next smallest ingredient amount and continues adding and doubling the size until all ingredients are integrated. |

| graduates | Compounding equipment used to measure the volume of liquid ingredients; generally glass or plastic cylinders and conicals. |

Overview of Prescription Compounding

Stability of Compounded Preparations

Compounding Records and Documents

Compounding Equipment and Procedures

Commonly Compounded Preparations

Additional Compounded Preparations

Extemporaneous Versus Batch Repackaging

Beyond-Use Dating and Labeling Personnel Training and Competency |

|

As the benefits of individualized drug therapy have been recognized over the past few decades, prescription compounding has experienced renewed popularity. It is estimated that 30 million compounded prescriptions are prepared each year, which comprises 1% of all dispensed prescriptions.1 Several thousand pharmacies have thriving practices in human and veterinary compounding; in fact, some are compounding-only pharmacies. Providing individualized patient care through compounding offers a unique clinical experience through the patientphysician-pharmacist triad.

When commercial medications are available but not in the packaging best suited to the needs of the patient or staff, repackaging offers a convenient, costeffective method of providing medications to the patient. The role of technicians in the preparation of nonsterile compounds and repackaging medications is very important.

While pharmacists evaluate patient needs, counsel patients, interact with other health care professionals, and perform other clinically oriented activities, technicians perform much of the actual dosage form preparation through compounding and repackaging medications.

While pharmacists evaluate patient needs, counsel patients, interact with other health care professionals, and perform other clinically oriented activities, technicians perform much of the actual dosage form preparation through compounding and repackaging medications.

Overview of Prescription Compounding

Prescription compounding allows the prescriber and the pharmacist to meet the unique needs of a patient. For example, a physician may determine that a patient requires a medication in a strength or dosage form that is not commercially available. Compounding is often associated with several specialty practice areas, including veterinary medicine, dermatology, hormone replacement therapy, pain management, hospice, and home care.

It is important to differentiate between compounding and manufacturing. Compounding involves the preparation, mixing, packaging, and labeling of a small quantity of a drug based on a practitioner’s prescription or medication order for a specific patient. This is contrasted with manufacturing, which is the production, conversion, and/or processing of a drug, generally in bulk quantities and without a prescription or medication order. In other words, compounding a preparation for a specific patient usually takes place in a pharmacy, whereas manufacturing products in bulk typically occurs in licensed manufacturing facilities.

It is also necessary to understand that sterile compounding is different from nonsterile compounding. Sterile compounds must be prepared using strict aseptic technique and include preparations such as injections, ophthalmic solutions, and irrigation solutions. Sterile compounding is explained in Chapter 16, Aseptic Technique, Sterile Compounding, and IV Admixture Programs. This chapter focuses on nonsterile compounding, which includes preparations such as oral and topical medications. The topics of pharmacy calculations ( Chapter 14) and processing medication orders and prescriptions (Chapter 13) are also important to understand in relation to compounding.

USP-NF Chapter 795

The United States Pharmacopeia and The National Formulary (USP-NF) offers guidelines and an enforceable set of standards describing procedures and requirements for compounding in Chapter 795 (Pharmaceutical Compounding–Nonsterile Preparations).2 The intent of the USP is to protect both patients and pharmacists.

Once a technician’s knowledge and proficiency have been demonstrated and documented, they are allowed to participate in the compounding process. The pharmacist is responsible for the finished product and quality assurance in all aspects of the compounding process. The intent and emphasis of USP Chapter 795 is summarized here in relation to nonsterile compounding.

RX for Success

All technicians involved in compounding must be properly trained, knowledgeable about USP Chapter 795 (Pharmaceutical Compounding–Nonsterile Preparations), and proficient with pharmaceutical calculations.

Compounding Environment

The compounding environment includes the facilities (i.e., compounding area) and equipment. The compounding area should have adequate space for the orderly placement and storage of equipment and support materials. Controlled temperature and lighting are needed for chemicals and finished medications. The area must be kept clean for sanitary reasons and to prevent crosscontamination. A sink with hot and cold running water is essential for hand washing and equipment cleaning. Compounding equipment must be appropriate in design and size for its intended purpose and must always be cleaned immediately after use. Equipment must be properly maintained and calibrated.

Some pharmacies compound both sterile and nonsterile preparations. In these pharmacies, the compounding area for sterile preparations is separate and distinct from the area used for compounding nonsterile preparations.

Some pharmacies compound both sterile and nonsterile preparations. In these pharmacies, the compounding area for sterile preparations is separate and distinct from the area used for compounding nonsterile preparations.

Stability of Compounded Preparations

Stability is defined in USP-NF as “the extent to which a preparation retains, within specified limits, and throughout its period of storage and use, the same properties and characteristics that it possessed at the time of compounding.”2 Primary packaging of the finished medication is of utmost importance. The choice of the proper container is guided by the physical and chemical characteristics of the finished medication. Whether the medication is light sensitive or binds to the container are examples of considerations in maximizing stability. Beyond-use labeling (i.e., the preparation is labeled with a beyond-use date) should be included on all medications. The beyond-use date is the date after which a preparation is not to be used and is calculated from the date it was compounded. Things to consider for determining beyond-use dates include whether the medication is aqueous (water-based) or nonaqueous, the expiration dates of the ingredients used, the storage temperature, and the references documenting the stability of the finished medication. Expiration dates apply to manufactured products.

Ingredient Selection

Sources of ingredients vary widely. USP or National Formulary (NF) chemicals are the preferred chemicals for compounding. Other sources may be used, but the pharmacist is responsible for ensuring that the chemical meets purity and safety standards. Manufactured medications (prescription and nonprescription drugs) are another acceptable source of ingredients. Any drug that is withdrawn from the market by the FDA should not be used.

Compounded Preparations

Preparations should contain at least 90%, but not more than 110%, of the labeled active ingredient, unless more restrictive guidelines apply. Compounding guidelines in USP-NF specifically address the following dosage forms: capsules, powders, lozenges, tablets, emulsions, solutions, suspensions, suppositories, creams, topical gels, ointments, and pastes.

Compounding Process

The goal of the compounding process is to “minimize error and maximize the prescriber’s intent.”2 Depending upon state laws and regulations, technicians who are trained in preparing compounded prescriptions may be involved in the steps listed in this section.

As stated in USP Chapter 795, the compounding process includes several steps and for quality assurance, it is suggested that the steps be accomplished in an orderly and methodical manner.

As stated in USP Chapter 795, the compounding process includes several steps and for quality assurance, it is suggested that the steps be accomplished in an orderly and methodical manner.

Prior to the technician compounding the preparation, the pharmacist clinically evaluates the appropriateness of the prescription or drug order in terms of safety and intended use for the patient. In addition, as these steps are reviewed, it is important to understand that only one preparation should be compounded at one time in the compounding area to avoid errors and cross-contamination.

1. Calculate the amount of ingredients needed for the preparation.

2. Identify equipment needed to compound the preparation. Compounding equipment is discussed later in this chapter.

3. Wash hands and wear proper attire. Clean clothing with a clean laboratory jacket is considered proper attire for most nonsterile compounding. It may, however, be necessary to wear head covering, safety glasses, gloves, mask, gown, and foot covers if the ingredient(s) in the compound are considered potentially hazardous. An example of compounding attire is shown in figure 15-1. These precautions are for the safety and protection of the individual preparing the compound. Procedures for working with an ingredient can be found in the Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS), which are forms readily accessible to all employees in the pharmacy (electronically or in hardcopy) for each drug substance in the compound. Pharmacists are responsible for instructing technicians on how to retrieve and interpret needed information from the MSDS.

4. Clean the compounding area and needed equipment.

5. Collect all materials and ingredients needed.

6. Compound the preparation following a formulation record (file of individually compounded preparations) or prescription and according to the art and science of pharmacy. Compounding procedures are discussed later in this chapter.

7. Document name on the compounding record/log. In addition to the name of the technician preparing the compound, the compounding record also includes the name, strength, and amount of preparation, formulation record reference, lot numbers of ingredients, name of the pharmacist checking the compound, date of preparation, prescription number (or other assigned identification number), and beyond use date.

8. Label the final preparation appropriately. The label should include the name of the preparation, strength, dosage form, quantity, beyond-use date, initials of the pharmacist checking the preparation, storage requirements, and any other statements or information that may be required by law.

9. Properly clean and store all equipment.

Figure 15–1. An example of compounding attire (laboratory jacket, gloves, and mask).

The pharmacist is responsible for checking the final preparation for weight variation, proper mixing, odor, color, consistency, and pH as appropriate. In addition, the pharmacist is responsible for signing and dating the prescription or drug order documenting and ensuring quality.

RX for Success

The pharmacist reviews each step in the compounding process and is responsible for accuracy, quality, completeness, and final checks prior to dispensing the prescription to the patient.

Compounding Records and Documents

Each step of the compounding process should be documented. USP Chapter 795 requires pharmacies to maintain a formulation record, also known as the master formula, and a compounding record for each compounded preparation. The formulation record is an individual record (like a recipe) that is stored in a file with other formulas. These are usually filed alphabetically, so it is easy to find the desired formula. This record includes a listing of the ingredients, compounding equipment, and instructions for preparing the formula.

The goal of documentation is for quality purposes, to allow another individual to reproduce the same formulation at a later date, and to trace each ingredient in the compound, if necessary.

The goal of documentation is for quality purposes, to allow another individual to reproduce the same formulation at a later date, and to trace each ingredient in the compound, if necessary.

The compounding record is the log (or record) of an actual compounded preparation (i.e., based on an individual prescription or drug order) or batch being prepared (i.e., for compounds prepared in anticipation of orders). It includes manufacturer and lot numbers of chemicals used, the date of preparation, an internal identification number (commonly called a lot number), a beyond-use date, the names of the individuals who prepared and verified the preparation, and any other pertinent information regarding the preparation. The compounding record for a batch (batch record) is usually filed by lot number, whereas the compounding record for an individual prescription or drug order is a chronological list of preparations made. Depending upon state laws and regulations, the formulation and compounding records may be maintained as paper copies or electronically in the pharmacy.

RX for Success

Always remember that accurate and complete documentation is essential in all aspects and areas of pharmacy.

Quality Control

Quality control is the final check on the preparation to ensure its safety and quality. The pharmacist must evaluate the finished preparation both physically and by reviewing the compounding procedure to be certain the preparation is accurate. Discrepancies should be noted and evaluated to determine if the preparation is acceptable.

Patient Counseling

Patient counseling is important with all medications, including compounded formulations. The patient should be counseled by the pharmacist on the correct use, storage, beyond-use date, and evidence of instability in the compounded medication.

Inactive Ingredients

In addition to the active, or therapeutic, ingredient(s), compounded medications may contain a number of inactive, or nontherapeutic, ingredients. Inactive ingredients are needed to prepare the formulation, but are not intended to cause a pharmacologic response. Inactive ingredients are also referred to as inert ingredients, added ingredients or substances, or excipients.

Examples of categories of inactive ingredients used in compounded prescriptions include diluents or fillers, binders, colorants, lubricants, flavorants, sweeteners, suspending agents, emulsifying agents or surfactants, coating agents, preservatives, perfumes, acidifying agents, alkalizing agents, vehicles, and wetting agents. Although they do not cause pharmacologic activity, inactive ingredients are a necessary part of the product, and the specific chemicals used as excipients must be named in the formula.

Compounding Equipment and Procedures

The compounding equipment found in a pharmacy depends upon the type and scope of compounding performed. The most common types of equipment are those used to weigh and measure ingredients in the preparation. An electronic or class A torsion balance is used to weigh solids (i.e., powders, crystals) needed for the compound (figure 15-2 A and B). The surface on which the balance rests must be stable and solid. It is essential that technicians develop a proficient and accurate technique when using balances. Powder papers or weigh boats are used to hold the solid being weighed and help to keep the balance pans clean and free of corrosion. Brass weight sets are used with class A torsion balances.

The balance must be maintained and calibrated regularly.

The balance must be maintained and calibrated regularly.

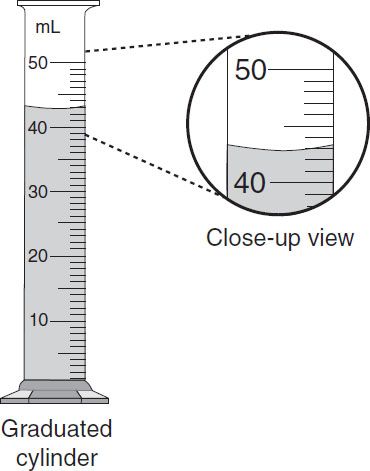

Graduates (i.e., glass or plastic cylinders and conicals) are used to measure the volume of liquid ingredients. Various sizes of graduates (e.g., 5 mL, 10 mL, 25 mL, 100 mL, 250 mL, etc.) are used when compounding (figure 15-3). It is recommended to use the smallest graduate that will hold the volume to be measured. In addition, it is important to measure the volume of liquid accurately by placing the graduate on a stable surface (i.e., counter top of work area) and read the measurement at the bottom of the meniscus. The meniscus is the natural curvature of the surface of the liquid and it is lower in the middle than at the edges. The bottom of the meniscus should be read at eye level. Do not look down or up at the bottom of the meniscus as this will yield an inaccurate reading (figure 15-4). In terms of graduates, the cylinder shaped graduates usually yield more accurate readings. Conical shaped graduates are often used when mixing liquids. The likelihood of error in accurately reading the bottom of the meniscus in a conical graduate increases as the sides flare. Pipets and calibrated syringes are used to accurately measure very small volumes of liquids.

Figure 15–2A. Class A torsion balance and weight set.

Figure 15–2B. Electronic balance with weigh boat.

Figure 15–3. Graduates (conicals and cylinders).

Figure 15–4. Measuring using a graduated cylinder. Read the bottom of the meniscus at eye level.

RX for Success

As part of quality assurance, it is essential to develop correct and accurate technique with all compounding equipment.