Epidermal tumors

Epithelial cysts

Appendageal tumors (i.e., follicular, sebaceous, apocrine, and eccrine)

Dermal and/or subcutaneous tumors (including fibrous tissue tumors, vascular tumors, neural tumors, and tumors of fat, muscle, cartilage, and bone)

Nonlymphoid infiltrative disorders (composed of “histiocytes” [macrophages] and mast cells)

Lymphoid infiltrates (including lymphomas and leukemias)

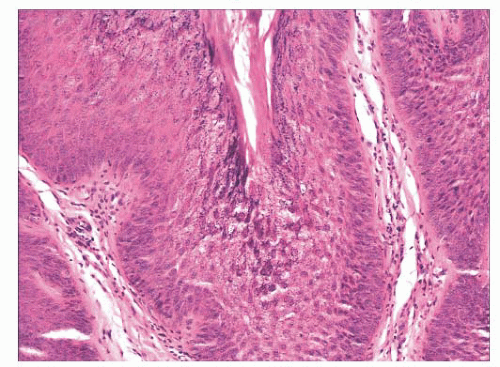

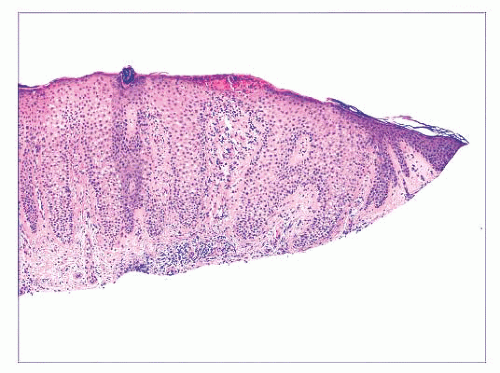

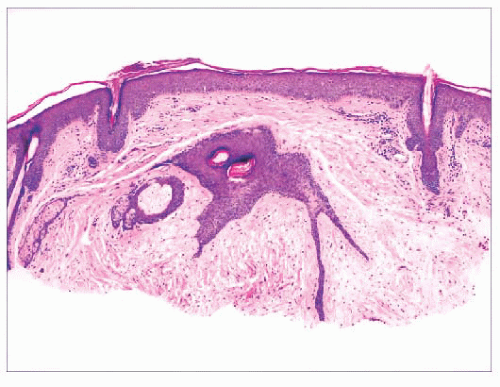

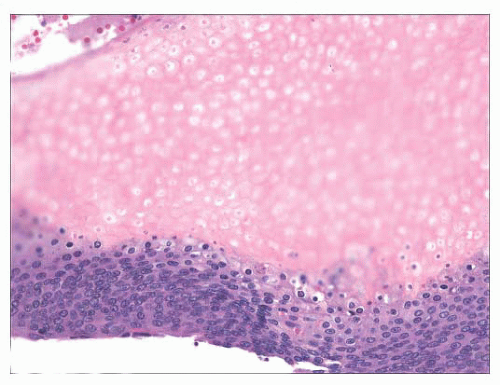

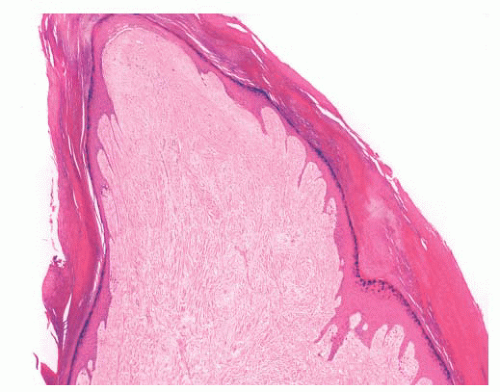

FIGURE 2.1 Epidermal nevus, showing papillomatosis and acanthosis. Note that the surface papillations are focally flattened. |

FIGURE 2.6 “Clonal” or nested seborrheic keratosis. The nests do not truly indicate a separate genetic clone of cells and are probably a manifestation of irritation. |

FIGURE 2.7 Prurigo nodularis, a reactive cutaneous lesion displaying pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. |

almost completely obscures the single-cell atypical junctional melanocytic proliferation. If the latter is suspected, additional levels or staining for MART-1 may be useful (19).

TABLE 2.1 Epidermoid Cysts of Follicular Origin/Differentiation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

degree of differentiation and by the appendage to which they appear to be differentiating (33). These schemes have been satisfying in many ways because they at least provide scaffolding upon which to build one’s understanding of these tumors. However, problems have arisen with this method, which can be summarized in the following manner:

The degrees of differentiation are subject to debate. For example, should syringocystadenoma papilliferum be grouped with the adenomas rather than the epitheliomas? Should poroma be considered an epithelioma rather than an adenoma?

The original grouping of sweat gland tumors into either the apocrine or eccrine category was based on a technique called enzyme histochemistry as well as conventional microscopic morphology. In recent years, réévaluation of these tumors both morphologically and by immunohistochemical methods has resulted in reclassification of many of the sweat gland tumors. Thus, many chondroid syringomas (cutaneous mixed tumors) are now regarded as apocrine rather than eccrine in differentiation (34), and although acrospiromas can be either apocrine or eccrine, apocrine differentiation is favored for most of them (35,36).

Although there are certainly many “classic” examples of adnexal tumors, others defy categorization because a given lesion may not only show different lines of differentiation but also different degrees of differentiation. This seems to be a common problem in consultation practice.

Adnexal carcinomas do not always fit comfortably into existing classification schemes.

TABLE 2.2 Ciliated Cysts of the Skin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

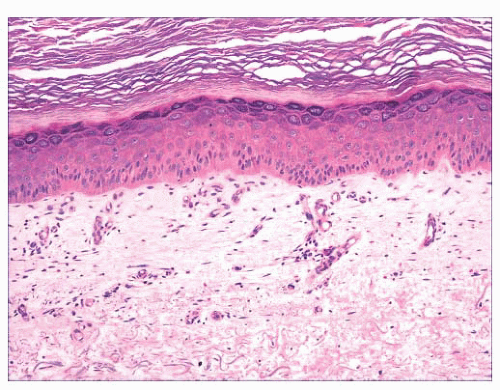

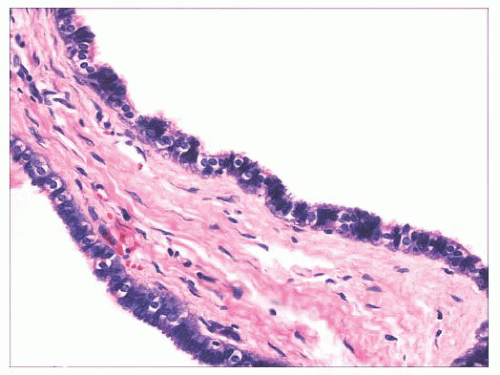

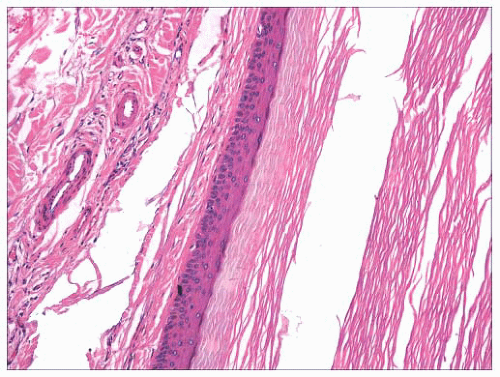

FIGURE 2.12 Epidermal (infundibular) cyst. The lining is composed of stratified squamous epithelium with a granular cell layer. Keratin contents are identified in the right portion of the figure. |

of clinical management. However, some of these tumors have a close relationship to genetically determined syndromes that may have significance in terms of proneness to internal malignancy or other health issues. Examples include multiple trichodiscomas and fibrofolliculomas (Fig. 2.15) (Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome) (37), trichilemmomas (Fig. 2.16) (Cowden syndrome) (38), or sebaceous tumors (Muir-Torre syndrome) (39). Progression of apparently benign adnexal tumors to malignancy has been reported in several instances (examples include pilomatrixoma, acrospiroma, and poroma). Finally, although knowledge of the precise differentiation pathway may not make a difference in the immediate clinical situation, an understanding of these tumors may lead to discoveries that could have significant impact in other areas of medicine.

mitoses can be observed in certain sweat gland tumors, such as acrospiroma, and some proliferating trichilemmal tumors can show both mitoses and foci of nuclear pleomorphism (43). Therefore, it is important to interpret these features in the overall context of the lesion, keeping in mind both the overall level of differentiation and the presence or absence of infiltration of the surrounding stroma. Second, intermediate levels of malignancy are increasingly being recognized among cutaneous adnexal tumors. An “intermediate-grade” lesion shows infiltration of connective tissues at the periphery of the tumor, whereas other histopathologic characteristics of malignancy (e.g., pleomorphism, cell necrosis, mitotic activity) may be less apparent. There is evidence that such tumors are prone to recurrences, sometimes accompanied by greater degrees of

cytologic atypia. Examples of such tumors have been seen in association with pilomatrixomas, proliferating trichilemmal tumors, clear cell hidradenomas (acrospiromas), and poromas.

FIGURE 2.17 Syringoma is a common adnexal tumor of eccrine differentiation often seen in the infraorbital region. |

FIGURE 2.18 Trichoepithelioma, desmoplastic type. Cords of epithelial cells and calcified horn cysts are identified. This is a tumor with follicular differentiation. |

TABLE 2.3 The Benign Adnexal Tumors | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

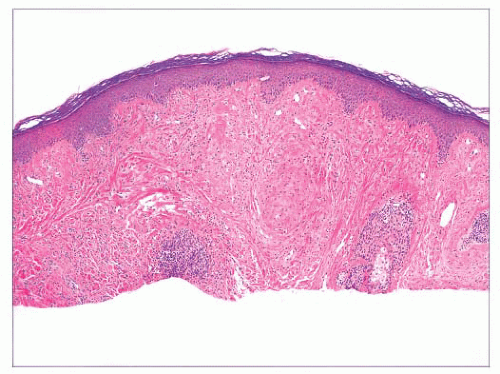

keratoses have arisen in individuals exposed to inorganic pentavalent arsenic. Actinic keratoses can progress to invasive squamous cell carcinoma at rates ranging from 0.1% to 10% (44). Metastases from actinic keratosis-related squamous cell carcinomas are uncommon, ranging in incidence from 0.5% to 3.0% (45,46). Microscopically, actinic keratoses often show atypia of the basilar or immediately suprabasilar keratinocytes, with nuclear crowding, pleomorphism, and irregular epithelial budding. Surface maturation of the involved epidermis is often preserved, at least initially, and adnexal epithelium is spared; in fact, it is believed that cells derived from these adnexal structures (e.g., hair follicles, eccrine sweat ducts) are responsible for the preservation of normal-appearing surface epidermis (Fig. 2.24) (47). However, with progression, greater involvement of the adnexa and surface epidermis occurs, so that eventually the entire thickness of epidermis may become atypical. Clinical and microscopic variants include bowenoid actinic keratosis, an actinic keratosis that has achieved full-thickness epithelial atypia (i.e., squamous cell carcinoma in situ) and resembles Bowen disease (see next section); atrophic or hypertrophic actinic keratosis; the spreading, pigmented actinic keratosis (showing overlapping features with solar lentigo) (48,49); and the acantholytic actinic keratosis, in which loss of cohesion among atypical basilar keratinocytes creates an image resembling various acantholytic dermatoses (50). The latter lesion can evolve into an invasive, acantholytic (“pseudoglandular”) squamous cell carcinoma. Lichenoid actinic keratoses combine the elements of typical actinic keratosis with a bandlike infiltrate that may partly obscure the dermal-epidermal interface (51). Diagnostic challenges may arise when attempting to distinguish actinic keratosis variants from nonmalignant acantholytic dermatoses (e.g., Grover disease, Darier disease), benign lichenoid keratosis, large cell acanthoma, solar lentigo, or early lentigo maligna. Other malignant or premalignant dermatoses that can microscopically resemble actinic keratosis include superficial basal cell carcinoma and forms of porokeratosis. It is not clear whether there is a difference in prognosis between the bowenoid actinic keratosis and true Bowen disease. One study has shown a similar histochemical profile for Bowen disease and bowenoid actinic keratosis using markers for p53 and p16 (52).

FIGURE 2.20 Eccrine poroma. Close-set basaloid cells with ductal differentiation are connected to the surface epidermis. |

FIGURE 2.21 Pilomatrixoma. This appendageal tumor with hair matrix differentiation features aggregates of basaloid cells with transition to eosinophilic keratinous material containing “shadow cells.” |

TABLE 2.4 Adnexal Carcinomas | ||

|---|---|---|

|

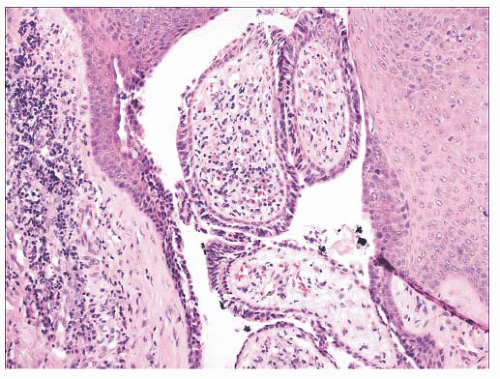

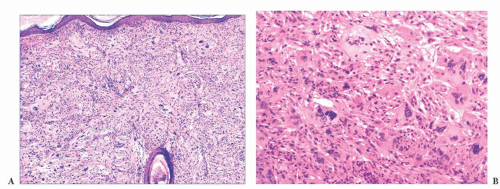

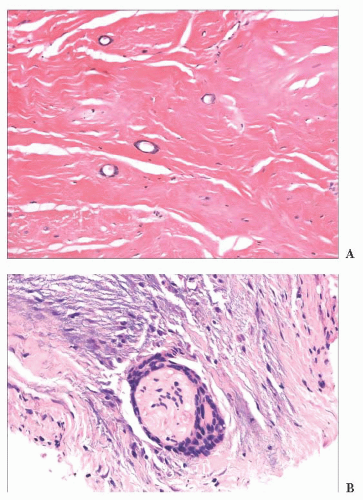

FIGURE 2.23 Microcystic adnexal carcinoma. (A). Small aggregates of duct-forming epithelial cells extend into the deep dermis. (B) Perineural invasion—a frequent finding in this tumor. |

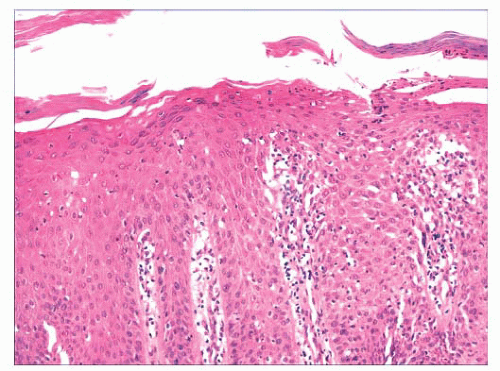

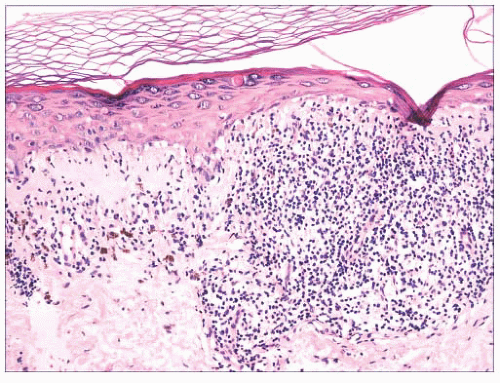

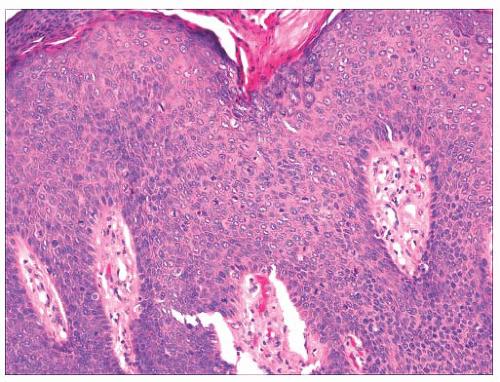

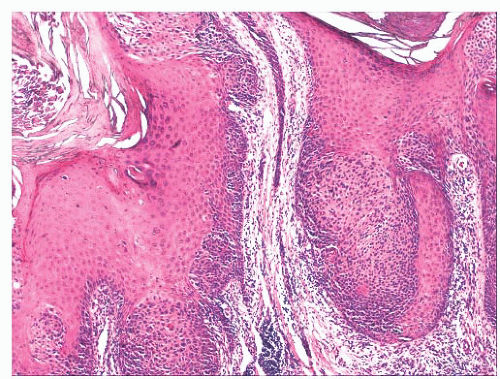

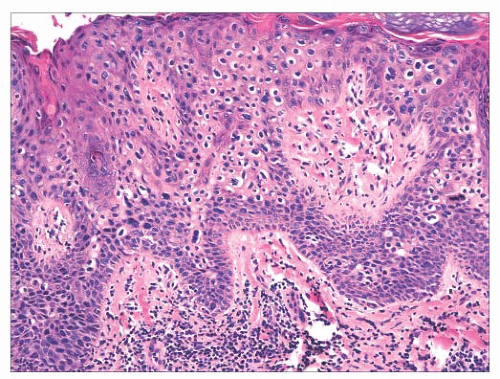

FIGURE 2.25 Bowen disease (squamous cell carcinoma in situ) showing full-thickness epithelial atypia. |

This has occurred, in part, because some lesions initially considered keratoacanthomas have metastasized (61) and, in part, because many immunohistochemical, ultrastructural, and genetic investigations have failed to reveal reliable differences from squamous cell carcinoma (62,63 and 64). Follicular derivation and a relationship to HPV infection has been supported by some studies (65).

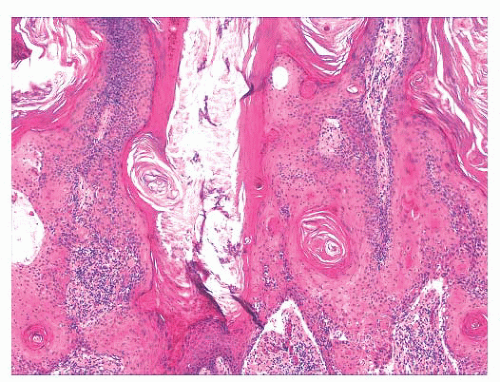

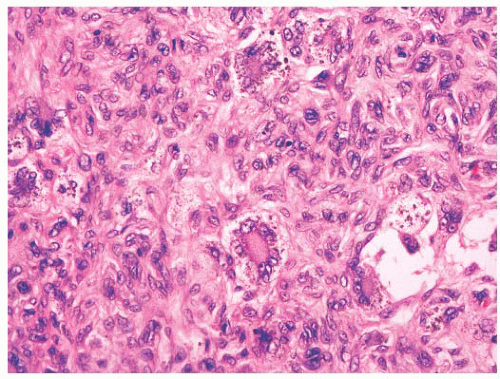

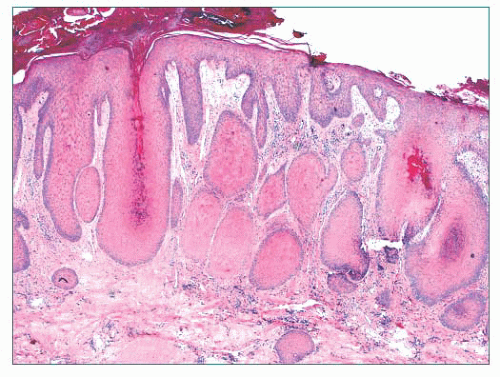

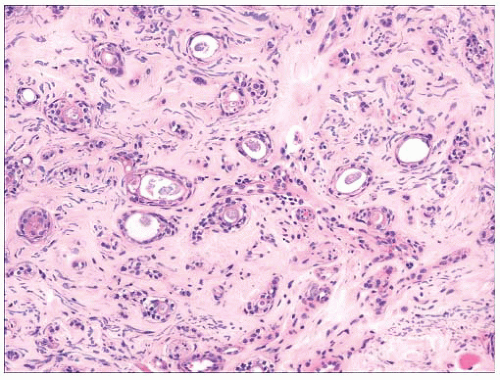

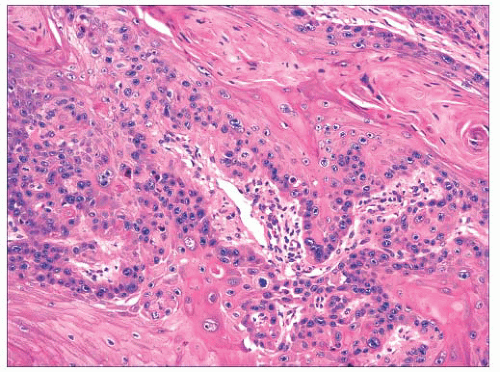

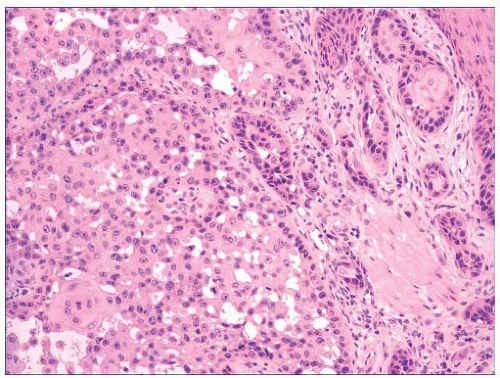

FIGURE 2.28 Squamous cell carcinoma. Masses of epithelial cells with cytologic atypia and foci of incomplete keratinization are shown. |

FIGURE 2.29 Pseudoglandular squamous cell carcinoma. Acantholysis of neoplastic cells produces a glandlike appearance, seen on the right of the figure. |

of cases, with involvement of regional lymph nodes, lung, or bone (77). This event is more likely among neglected tumors.

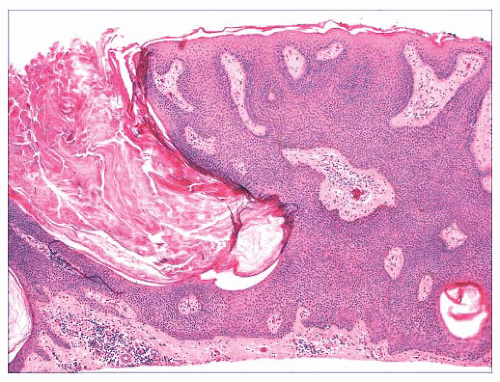

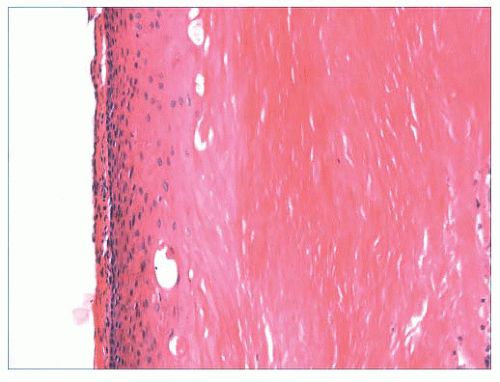

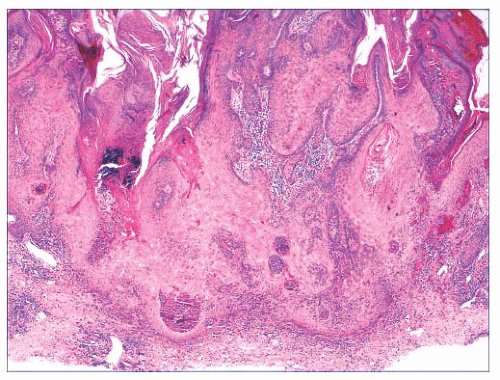

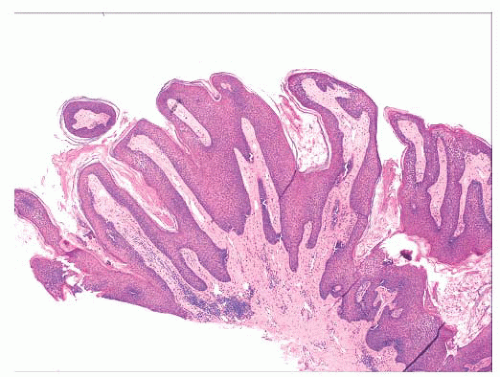

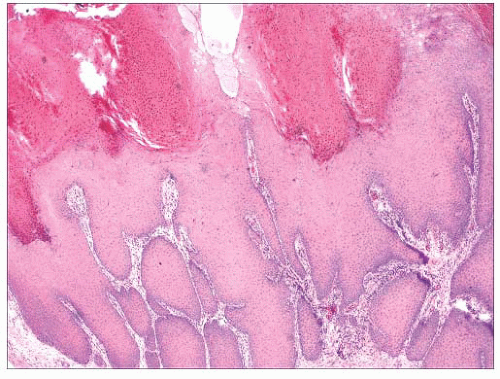

FIGURE 2.30 Verrucous carcinoma. Marked acanthosis with blunt, “pushing” margins and keratin-filled crypts can be seen. |

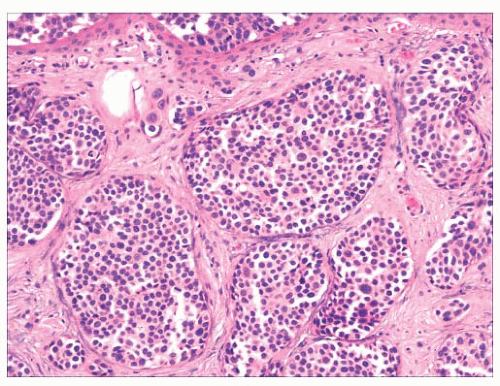

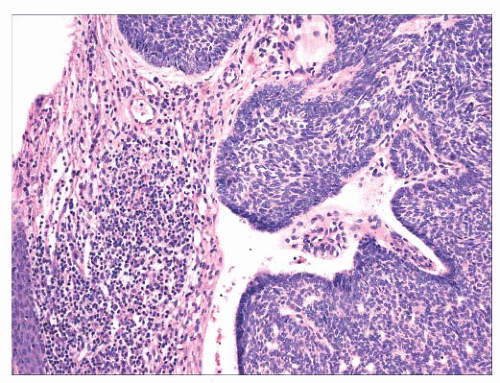

FIGURE 2.31 Basal cell carcinoma. Macronodular lesion features islands of basaloid cells, peripheral palisading, and cleftlike separations from the adjacent connective tissue. |

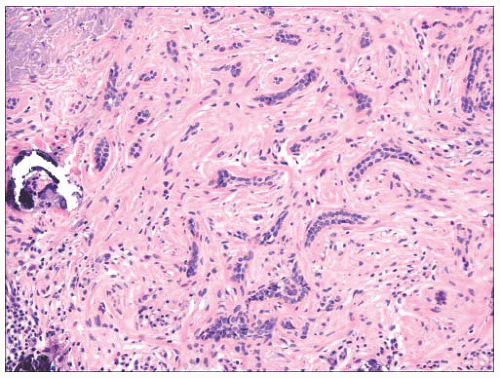

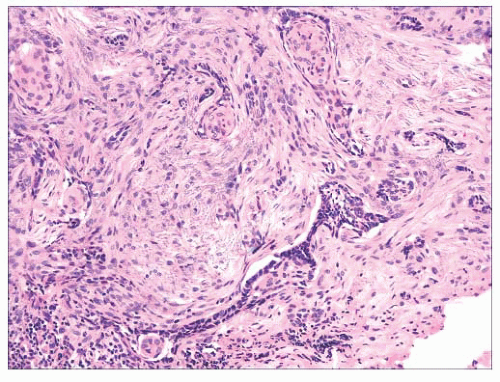

FIGURE 2.32 Infiltrative basal cell carcinoma showing cords of tumor cells within a cellular stroma. |

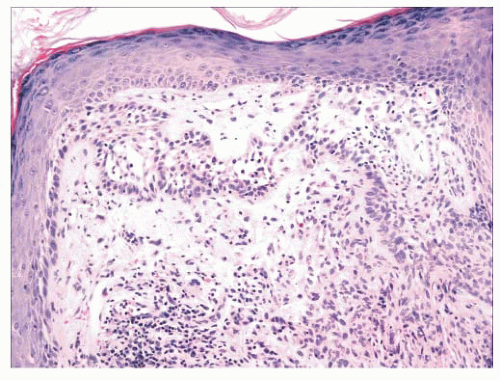

FIGURE 2.33 Superficial basal cell carcinoma. Islands of basaloid cells are closely associated with the surface epidermis. |

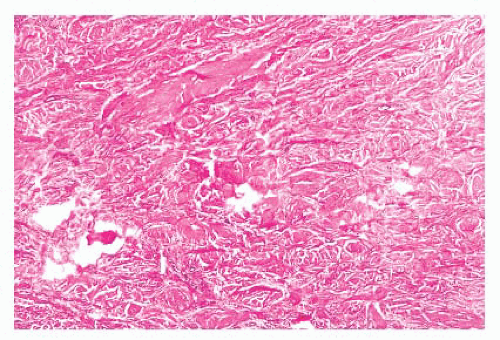

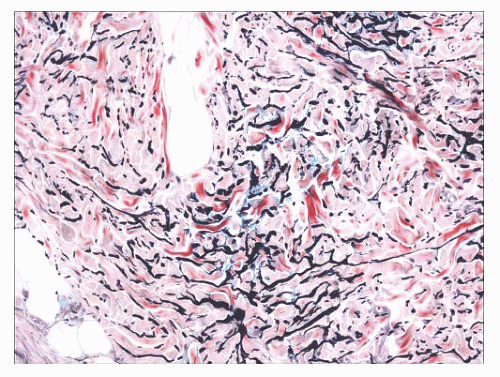

indurated papules (90,91) or nodules that may be organized in plaques or appear in disseminated form. The epidermis tends to be uninvolved, although lesions with combined features of epidermal nevus or Becker nevus have also been reported (92). In one variant, the Buschke-Ollendorff syndrome, connective tissue nevi are associated with osteopoikilosis—sclerotic, stippled densities in long, round, and flat bones. Microscopically, thickened collagen bundles are observed, either in compact or complexly interwoven form (Fig. 2.34). Stains such as Verhoeffvan Gieson often show elastic fibers that are abnormally distributed; increased in number and density (nevus elasticus); or fragmented, diminished, or even absent (nevus anelasticus) (93,94). Increased quantities of mucin can sometimes be identified (nevus mucinosus) (95), and we have observed a few cases in which patchy increases of elastic fibers have been associated with increased quantities of mucin deposition in the same locations (Fig. 2.35). The changes in connective tissue nevi can be subtle, especially in hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections. One must also take into account the anatomic region from which a biopsy has been obtained, because dermal collagen may be particularly thick in portions of the trunk or overlying large joints. Therefore, the diagnosis depends heavily on a high index of suspicion and a good clinical history.

for hemangiomas, telangiectasias, and atypical melanocytic lesions; the latter occurs especially when there is overlying junctional melanocytic hyperplasia, which is a finding that is not unusual in fibrous papules.

FIGURE 2.37 Digital fibrokeratoma, featuring hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, thick collagen bundles, and vasodilatation. |

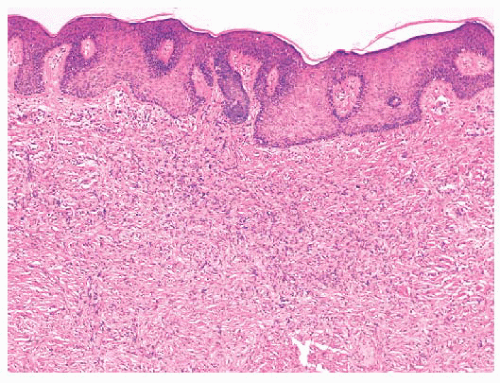

FIGURE 2.38 Dermatofibroma. Dermal proliferations of small spindled cells with overlying acanthosis are seen. |

accompanying the tumor rather than the major constituent cells (122). This marker also may not be expressed in the aneurysmal variant (122). On the other hand, the cells of epithelioid cell histiocytoma are often strongly factor XIIIa positive. CD68 and smooth muscle actin may be expressed as well, the latter often in tumors with a myofibroblastic component. The differential diagnosis in a given case can include neurofibroma or spindle cell melanocytic lesions (S-100 positive), leiomyoma (muscle-specific actin and desmin positive), or dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (CD34+).

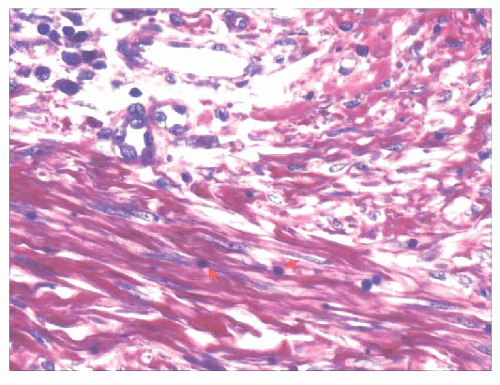

FIGURE 2.40 Infantile digital fibroma. There are thick, intersecting collagen bundles and accompanying spindled cells, many of which are myofibroblasts. |

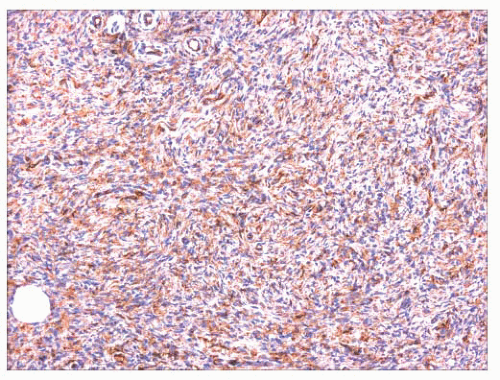

flattening of the tips of rete ridges, is rarely observed. Little or no polarizable collagen can be found among neoplastic cells (131). A pigmented variant, known as the Bednar tumor, also features scattered dendritic melanocytes (132). Occasionally, myxoid changes are seen, sometimes, but not invariably, in recurrent lesions (133,134). Fibrosarcoma-like areas occur, and their presence has been associated with local recurrence and metastasis (135,136). CD34 positivity of tumor cells is considered an immunohistochemical hallmark of DFSP (Fig. 2.43) (137). Fusion of the collagen gene COL1A1 to the plateletderived growth factor beta-chain (PDGFB) gene has been repeatedly described and is considered a characteristic genetic marker of DFSP (138).

FIGURE 2.41 Infantile digital fibroma. Phosphotungstic acidhematoxylin stain shows purple-staining paranuclear inclusion bodies that are about the size of erythrocytes (arrows). |

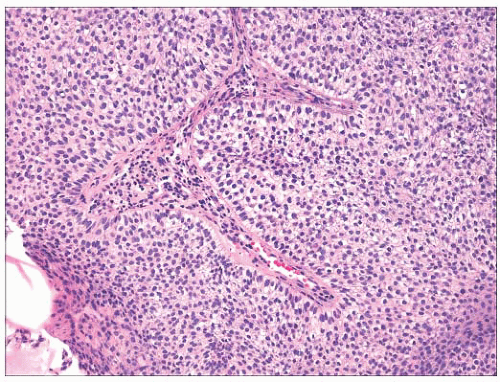

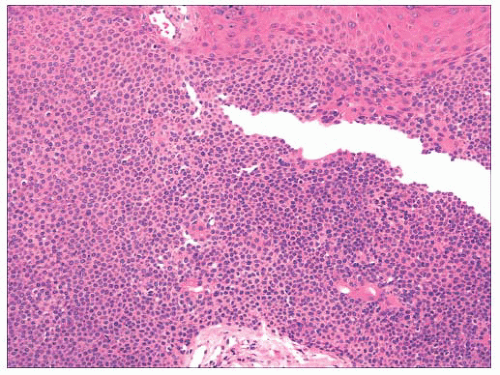

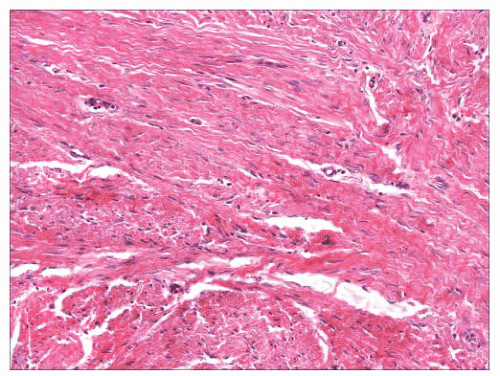

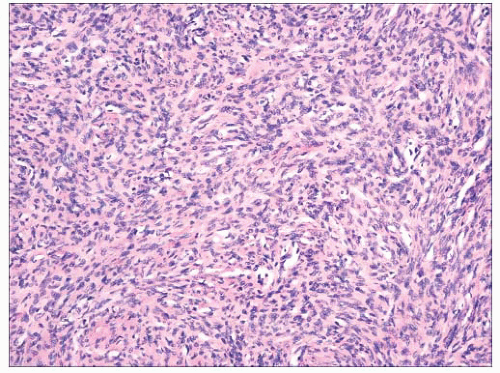

FIGURE 2.42 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dense aggregates of spindled cells forming “cartwheel arrangements.” The cells have a monotonous appearance. |

FIGURE 2.43 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. The constituent cells are CD34+, a hallmark of this neoplasm. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree