Non-Neoplastic and Tumor-Like Conditions of the Ovary

Tumor-Like Lesions Associated with Pregnancy

Luteomas of Pregnancy (Nodular Theca–Lutein Hyperplasia of Pregnancy)

Multiple Theca–Lutein Cysts (Hyperreactio Luteinalis)

Solitary Luteinized Follicular Cysts of Pregnancy and Puerperium

Leydig (Hilus) Cell Hyperplasia

Ovarian Granulosa Cell Proliferations of Pregnancy

Primary Ovarian Trophoblastic Disease

Reactive Stromal Tumor-Like Lesions

Ovarian Remnant Syndrome (Residual or Remnant Ovary Syndrome)

Ovarian ‘Drilling’ for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

Iatrogenic Disorders of the Ovaries

Ovarian Hemorrhage and Adnexal Torsion

Dysfunctional Cysts

Definitions

Dysfunctional ovarian cysts derive from the follicular apparatus either before or after ovulation (Table 24.1). They may result from or cause disordered hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian function. Although not always functional in the sense of producing steroid hormones, the cysts all have or have had the potential to do so at some stage in their development.

‘Polycystic ovaries’ is a term that should be reserved for the abnormal ovaries found in association with functional hyperandrogenism (the Stein–Leventhal and related clinical syndromes; see later). The ovaries commonly have thick white capsules, and display multiple cystic follicles and small, luteinized follicular cysts of atretic type, absence of stigmata of recent ovulation, and occur with a characteristic disturbance of hypothalamic–pituitary function. Ovaries displaying several cysts, but otherwise not fitting into this category, should be called ‘multicystic’ to avoid confusion.

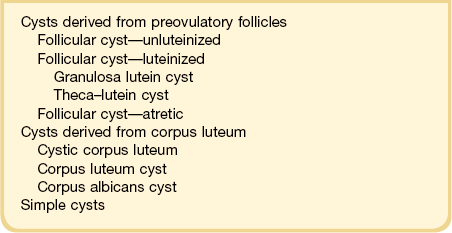

Features distinguishing the various types of cysts derived from the follicular apparatus appear diagrammatically in Figure 24.1.

Cysts Derived From Preovulatory Follicles (Follicular Cysts)

Etiology

The etiology of follicular cysts (by definition ≥3.0 cm) is not always obvious but in most cases reflects disordered function of the pituitary–ovarian axis. Pathologic cystic change may develop either in the follicular growth phase or during atresia. Unluteinized follicular cysts (Figure 24.1A), which produce predominantly estradiol, result from excessive ovarian stimulation (either by endogenous follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) or by ovulation-induction agents) or an abnormal response to normal stimulation.

Granulosa lutein cysts are follicular cysts with predominantly luteinized granulosa cells (which are internal to the basal lamina; see Figure 24.1B). Like corpora lutea, the granulosa cells secrete progesterone. An unknown proportion of granulosa lutein cysts results from failure of follicular rupture at the expected time of ovulation and is the basis of the luteinized unruptured follicle syndrome, which occurs more frequently in infertile than in normal fertile women.1

Theca–lutein cysts are follicular cysts with luteinization predominantly of the theca interna (which is external to the basal lamina; see Figure 24.1C). Androstenedione is the characteristic steroid product. These cysts develop when there is prolonged exposure to luteinizing hormone (LH) or beta human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG), either endogenous, such as in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS; see later) or hyperreactio luteinalis syndrome of pregnancy (multiple theca–lutein cysts), or exogenous, as in the ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Atretic follicular cysts can also elaborate androstenedione.

Clinical Features

Ovarian cysts in the fetus are more frequent than were once thought, with an estimated incidence of about one in 2500 births. They are usually diagnosed in the third trimester by ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).2 A cyst size below 4–5 cm usually carries a low risk of torsion, whereas larger cysts have a high risk, and therefore may warrant decompression. However, the criteria and recommendations for therapy vary widely.2–4 Since torsion can lead to ovarian loss and thus impact future fertility, the goal of intervention is to preserve fertility.2,6 Therapeutic intervention is usually prompted by acute torsion in the newborn or persistent cysts exceeding 5 cm in diameter in children older than 6 months of age.

In prepubertal girls, follicular cysts form a significant proportion of ovarian lesions that come to surgical intervention. Common clinical presentations are pain, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation, sometimes precipitated by ovarian torsion. A less common but well-recognized association is with isosexual pseudoprecocity, either idiopathic or associated with hypothyroidism or the McCune–Albright syndrome (polyostotic fibrous dysplasia, cutaneous melanin pigmentation, and endocrine organ hyperactivity).7,8

During the reproductive years, unluteinized follicular cysts may produce sufficient estradiol to cause irregular or prolonged (dysfunctional) uterine bleeding. The endometrium in such cases may show disordered proliferative phase changes or hyperplasia. Granulosa lutein cysts secrete progesterone, but rarely in sufficient amounts to disturb the menstrual cycle. Atretic cysts, if numerous (as in the PCOS), may synthesize sufficient androstenedione to produce hirsutism or virilization. Observation shows that most regress spontaneously over a few cycles and that therapy with contraceptive agents does not accelerate this process.9,10 Persistence should raise the suspicion of neoplasia.

Microscopic Features

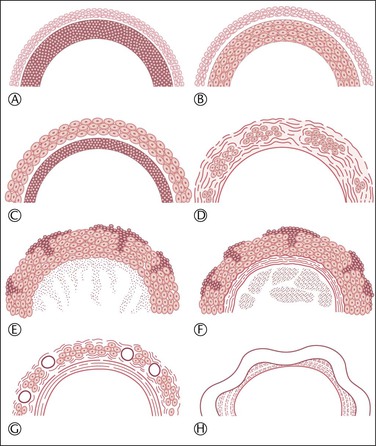

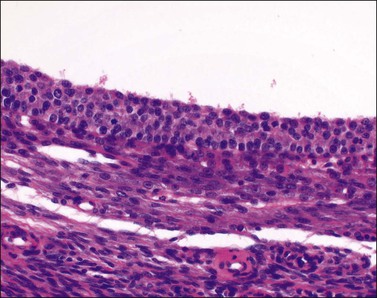

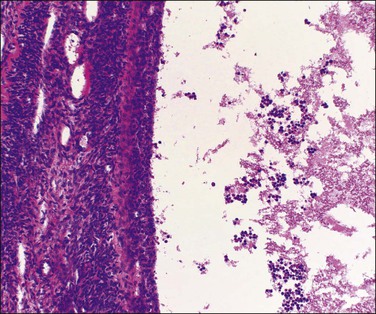

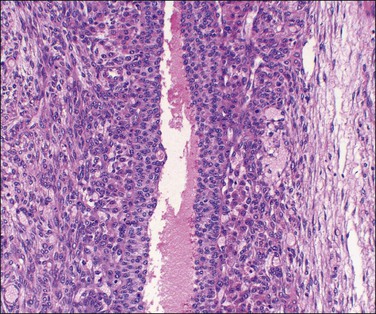

Unluteinized follicular cysts show the microscopic features of physiologic growing cystic follicles, with well-preserved granulosa and theca layers separated by a basal lamina (Figure 24.2). However the cumulus oophorus and oocyte are no longer present. The lining may be somewhat attenuated secondary to dilatation. There is no trace of the festooned pattern of a corpus luteum. During involution the lining is often incomplete and later appears as small clusters of lutein cells in the compressed ovarian stroma, which becomes progressively fibrotic. As involution continues, distinguishing features become increasingly difficult to identify and definitive diagnosis may not be possible (Figure 24.3); in this situation the cyst is better designated ‘simple’ (see later).

Figure 24.2 Unluteinized follicular cyst. About four layers of uniform small granulosa cells are present above the basal lamina.

Figure 24.3 Involuting follicular cyst. Smooth internal contour and inapparent lining cells of follicular origin. Shed granulosa cells in the lumen are a useful guide to diagnosis.

Luteinized follicular cysts show the general features of unluteinized follicular cysts as described above, but in addition some of the cells in the cyst wall are luteinized. The granulosa (granulosa lutein cyst; see Figure 24.4) or theca layer (theca–lutein cyst; see Figures 24.5 and 24.6), or occasionally both, luteinize, although the cyst is classified according to the layer predominantly affected. Luteinization appears as enlarged cells with increased eosinophilic or finely vacuolated cytoplasm. The changes are similar to those in a corpus luteum.

Figure 24.4 Granulosa lutein cyst lined by large eosinophilic cells. The thecal layer is relatively inconspicuous.

Figure 24.5 Theca–lutein cyst. Thick lining of small granulosa cells with large luteinized theca cells beneath basal lamina (from patient with PCOS).

Cytologically, luteinized follicular cysts contain single and/or clusters of luteinized granulosa cells with round to oval nuclei, coarse chromatin, and small prominent nucleoli. Cell cytoplasm is ample and foamy. Mitotic figures may be found. The cells lack pleomorphism. Degenerative changes may be present in single cells with obvious nuclear pyknosis.

Corpus Luteum Cysts

Gross Features

Corpora lutea of menstruation rarely exceed 3 cm (average size 2 cm) but may do so if there is an unusually large fluid-filled central cavity. Cystic corpora lutea of pregnancy often exceed 5 cm and may exceed 10 cm in diameter. They are not infrequently identified on routine ultrasound examination in early pregnancy. They contain clear fluid or altered blood. Rupture may be evident. They are generally smooth lined with an incomplete band of yellow tissue in the wall.

Microscopic Features

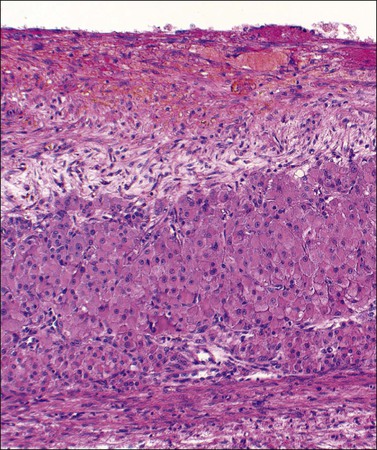

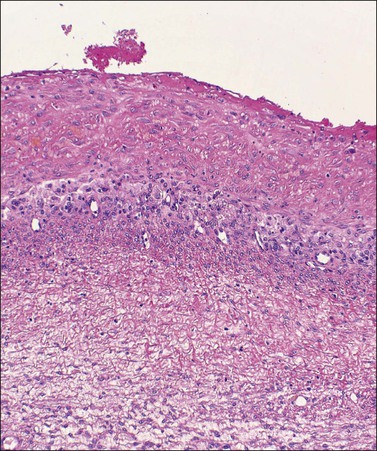

Cystic corpora lutea display the same features as their non-cystic counterparts. The distension leads to some attenuation of the convolutions but without loss of distinctive cell layers. The fibrous tissue lining contains mature collagen demonstrable with a trichrome connective tissue stain. Peripheral clusters of small paralutein (theca–lutein) cells may still be seen between larger groups of granulosa lutein cells (Figure 24.7). The granulosa and theca–lutein cells are smaller than those seen in a fresh corpus luteum. The nuclei are small, hyperchromatic, and lack mitotic activity, while the cytoplasm is usually finely vesicular. With progressive involution, fewer and smaller islands of lutein cells are found within the increasingly fibrotic wall, but a well-defined zone of small blood vessels remains to mark the phase of vascularization (Figure 24.8).

Figure 24.7 Early corpus luteum cyst. Organizing hematoma at top and thin zone of involuting vacuolated luteinized cells below.

Figure 24.8 Late corpus luteum cyst. Inner zone of fibrous tissue with involuting vacuolated luteinized cells beneath.

Simple (Unclassified) Cysts

Microscopic Features

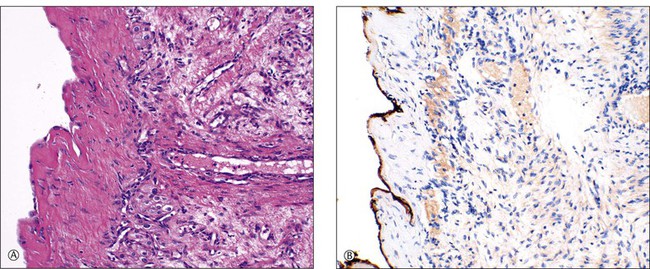

The lining usually consists only of a narrow band of dense fibrous tissue or compressed ovarian stroma. There may be occasional small clusters of involuting lutein cells in the cyst wall, suggesting an origin from the follicular apparatus. Sometimes there is a complete or partial lining of apparent epithelial cells that are too attenuated for their origin to be identified (Figure 24.9A) but, even here, persistent reactivity for α-inhibin may be present (Figure 24.9B). Some cysts undoubtedly represent epithelial cystomas. Some are lined by granulation tissue or organizing hematoma. Such lesions may be endometriotic in origin but lack overall the necessary diagnostic features. There is probably no benefit in precisely categorizing ‘simple’ cysts. All are benign and most are non-neoplastic.

Figure 24.9 Simple cyst. (A) A dense fibrous tissue wall is lined by barely perceptible ‘epithelial’ cells. Occasional lutein-like cells beneath this fibrous layer suggest origin from the follicular apparatus. (B) Persistent α-inhibin reactivity in the lining cells (as well as the lutein-like cells in the wall) support this interpretation.

Tumor-Like Lesions Associated with Pregnancy

Luteomas of Pregnancy (Nodular Theca–Lutein Hyperplasia of Pregnancy)

Microscopic Features

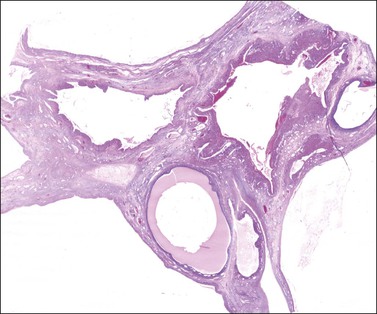

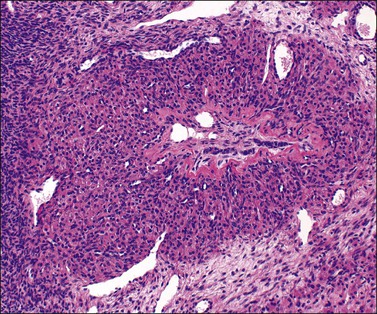

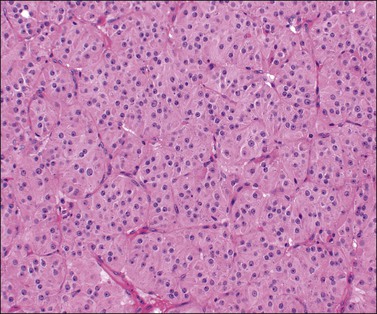

Luteomas display sheets of large eosinophilic cells that are broken up into groups by numerous delicate blood vessels. An organoid pattern (Figure 24.10) is common. A trabecular arrangement is less frequently seen. The cell size is intermediate between that of granulosa and theca–lutein cells. The reticulin pattern of fibers around groups rather than individual cells is also intermediate between the abundant pericellular distribution of reticulin fibers in the theca interna and the paucity of fibers in the granulosa layer. Follicular spaces containing colloid-like material may be present but the intracellular hyaline droplets (‘colloid bodies’) typical of corpora lutea of pregnancy are rare. The cytoplasm is eosinophilic and sometimes finely vacuolated but contains little stainable lipid. The round central nuclei have a prominent nucleolus and abundant euchromatin. There may be mild nuclear pleomorphism and some mitotic figures (<3 per 10 HPF) (Figure 24.10). The remainder of the ovary shows the physiologic changes of pregnancy but small theca–lutein cysts may be evident as well. Early involutional changes include nuclear pyknosis and increased cytoplasmic vacuolization. Eventually the luteoma is reduced to sheets of necrotic cells (Figure 24.11). Even at this late stage, the typical reticulin pattern may still be useful diagnostically.

Figure 24.10 Luteoma of pregnancy. Distinctly organoid pattern with cell groups separated by delicate vessels. Note mild nuclear variation.

Differential Diagnosis

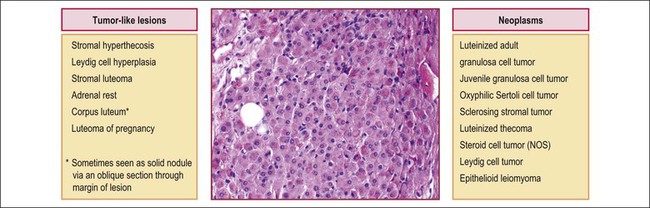

Non-cystic aggregates of large lutein-like cells include a plethora of entities in the differential diagnosis, some neoplastic, some not (Figure 24.12). The clinical context and gross features of the lesions all contribute to their separation.

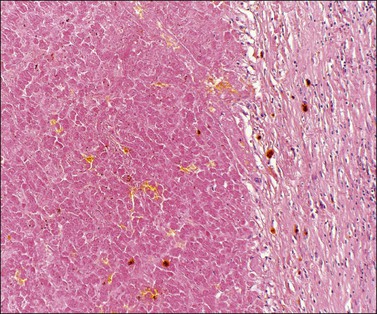

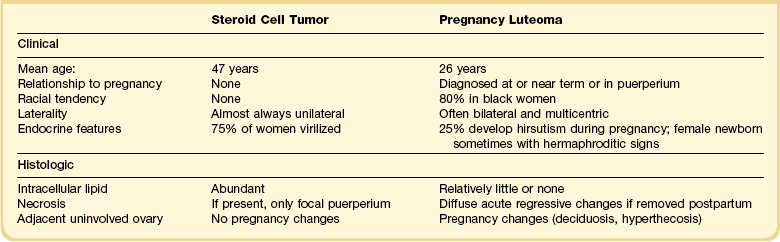

Steroid cell tumors are almost always unilateral (excepting for stromal luteomas) and sometimes arise in the ovarian hilus. They are solid, lobulated tumors composed of eosinophilic or finely vacuolated cells arranged in a diffuse or, less commonly, a trabecular pattern—not dissimilar to that of luteomas. Reticulin surrounds single cells or small groups. Mitotic activity is variable but rarely as prominent as in luteomas of pregnancy. The most helpful distinguishing microscopic features are the abundant stainable intracytoplasmic lipids in all steroid cell tumors and the presence of crystalloids of Reinke in Leydig cell tumors (Table 24.2).

Multiple Theca—Lutein Cysts (Hyperreactio Luteinalis)

Etiology and Clinical Features

While theca–lutein cysts (luteinized follicular cysts) occur at any age and in many different clinical situations, multiple bilateral theca–lutein cysts are classically associated with molar pregnancies or choriocarcinoma, occurring in 25% of such cases. They also occur with Rh isoimmunization, nonimmune hydrops, chronic renal failure,11 multiple pregnancies,12 and even apparently normal singleton pregnancies.13,14 Rarely, a similar clinicopathologic picture results from ovarian hyperstimulation, provoked by ovulation-induction agents (see later), a condition occasionally associated with clinical evidence of hyperglycemia or virilization.15 Although multiple bilateral theca–lutein cysts are usually associated with abnormally elevated β-hCG levels, additional factors may be necessary for their genesis. The cysts may persist into, or appear first, in the puerperium when β-hCG levels have fallen. In the latter situation the cysts probably initially developed during pregnancy under the influence of β-hCG but were then maintained by the FSH and LH levels that rose soon after parturition if lactation was not established. The condition almost always regresses within a few weeks after parturition. For this reason surgery during pregnancy, which is often required for diagnostic purposes or management of acute abdomen or shock, should be as conservative as possible. Intraoperative frozen-section examination of an incisional ovarian biopsy may obviate unnecessarily extensive surgery based on the erroneous presumption of malignant disease.

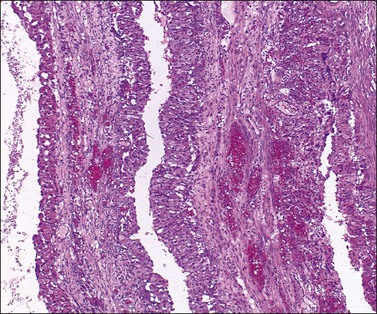

Gross and Microscopic Features

Both ovaries are involved and measure up to 15 cm across. Sectioning shows multiple cysts 1–4 cm in diameter that contain yellowish fluid or blood, separated by edematous stroma (Figure 24.13). The follicular cysts show hyperplasia and prominent luteinization of the theca interna layer; the granulosa is often luteinized as well (Figures 24.6 and 24.14). The edematous stroma may also contain large clusters of luteinized stromal cells.

Figure 24.13 Multiple theca–lutein cysts in pregnancy. Multiple cysts and intervening hemorrhagic edematous stroma.

Figure 24.14 Hyperreactio luteinalis. Detail of Figure 24.6. Luteinization of both theca and granulosa with some early necrosis (cytoplasmic eosinophilia) of the lining (at top).

Solitary Luteinized Follicular Cysts of Pregnancy and Puerperium

Definition

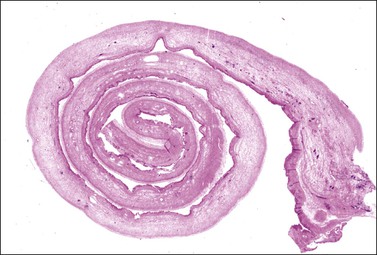

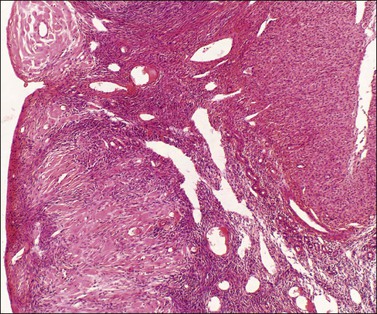

A large, distinctive follicular cyst of the ovary may occur during pregnancy.16,17 Such cysts present as adnexal masses in the third to fourth months of pregnancy or postpartum, or are incidental findings at cesarean section. The involved ovaries exhibit large (average diameter 25 cm), unilocular, thin-walled cysts (Figure 24.15), which contain clear or mucoid fluid. The pathogenesis is unknown, but β-hCG stimulation is probably important.

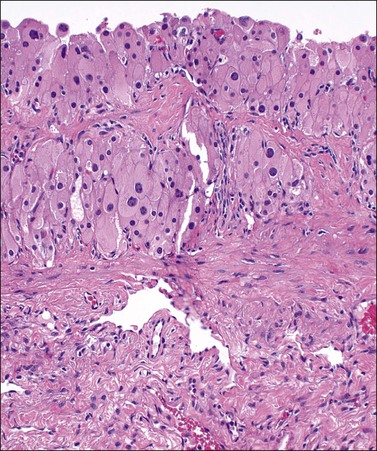

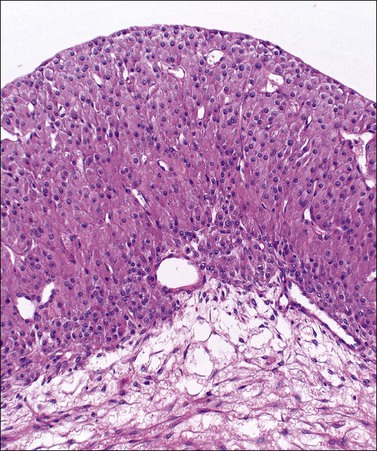

Microscopic Features

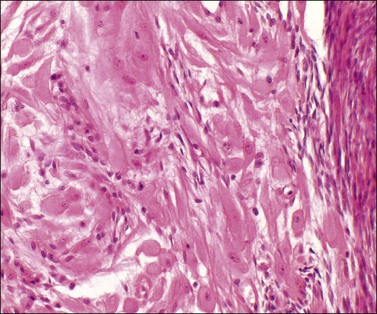

Microscopically, a single layer or multiple layers of large luteinized cells line the cysts, with only a sparse reticulin network. Similar cells are sometimes also present in the fibrous wall of the cysts but these cells are not obviously thecal in type, i.e., there is no clear definition of the granulosa and theca elements of the cyst wall usually seen in cysts of follicular origin. A striking feature is the focal presence of large, pleomorphic and hyperchromatic nuclei in the luteinized cells (Figure 24.16). This feature, together with the remarkably large cyst size and lack of recognizable separation of lining cells into granulosa and theca layers, distinguish this entity morphologically from the follicular cysts of non-pregnant women. Mitotic figures are lacking.

Deciduosis (Ectopic Decidua)

Gross and Microscopic Features

Deciduosis appears as serosal macules 1–5 mm across, which are flat or slightly raised in contour. Decidual foci consist of superficial discrete collections of cells cytologically similar to the decidual cells of gestational endometrium, i.e., distinct cell margins, abundant, slightly eosinophilic, finely granular cytoplasm, and central, small, round pale nuclei with conspicuous nucleoli. Capillaries are prominent and the decidual cells sometimes appear to sheathe them. A sprinkling of lymphocytes may be present (Figures 24.17 and 24.18). Most commonly the foci are nodular or plaque-like but some lie just beneath the serosal surface and are surrounded by edematous stroma. Decidual foci may become confluent.

Figure 24.17 Ovarian deciduosis. Subserosal plaque, with central capillary, plus clustered decidual cells in adjacent cortex. Note stromal luteinization below.

Figure 24.18 Detail of deciduosis (same case as Figure 24.17). Decidual cells showing abundant cytoplasm, round to oval nuclei with prominent nucleoli. Occasional lymphocytes present.

Ovarian Granulosa Cell Proliferations of Pregnancy

Definition

Proliferations of granulosa cells occur rarely as incidental findings in pregnant women. The lesions are usually multiple and are present within atretic follicles.18

Microscopic Features

The arrangement of the granulosa cells mimics similar patterns seen with granulosa cell tumors, i.e., solid, microfollicular, trabecular, or insular (Figure 24.19). Usually, the granulosa cells contain scanty cytoplasm and grooved nuclei resembling the cells of the adult-type granulosa cell tumor. Less commonly, the cells are luteinized with non-grooved nuclei of variable size, or sertoliform with vacuolated cytoplasm suggestive of lipid.

Ovarian Pregnancy

Definition

• The tube must be intact and clearly separate from the ovary.

• The fetal sac should occupy the normal position of the ovary and be connected to the uterus by the utero-ovarian ligament.

• Definite ovarian tissue must be present in the sac wall. These criteria obviously become more difficult to establish in more advanced gestations. In these cases confirmation of ovarian pregnancy requires the demonstration of ovarian tissue at several places in the fetal sac wall.

• The serum β-hCG should fall to non-pregnant levels upon removal of the ovarian lesion.

Etiology

Ovarian nidation occurs about once in every 10,000 pregnancies and accounts for 0.5–3% of ectopic gestations.19–21 Exceptionally rarely, the ovarian nidation may be multiple,22 or occur with a synchronous intrauterine pregnancy.23,24 A strong relationship exists between ovarian ectopic pregnancies and use of intrauterine contraceptive devices, but the nature of this relationship remains unclear.20 In marked contrast to patients with tubal ectopics, patients with ovarian pregnancies are highly fertile and have a lower than average incidence of pelvic inflammatory disease and endometriosis. The pathogenesis is best explained by chance fertilization of an unexpectedly mature ovum within the fimbriae, or on the ovarian surface, and subsequent implantation in the ovarian parenchyma. Intrafollicular implantation and development of the conceptus within the corpus luteum itself is considered highly unlikely. This is not only because the ovum would not have completed its first meiotic division and matured to the point of being able to accept fertilization, but also because of the inhospitable environment in the hemorrhagic corpus luteum. Ovarian endometriosis is thought to play no role in local nidation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree