central nervous system (CNS): the control center, made up of the brain, the brain stem, and the spinal cord

peripheral nervous system: motor and sensory nerves that connect the CNS to remote body parts and relay and receive messages from them

autonomic nervous system (part of the peripheral nervous system): regulates involuntary functioning of the internal organs and vascular system.

The dura mater, or outer sheath, is made of tough white fibrous tissue.

The arachnoid membrane, the middle layer, is delicate and lacelike.

The pia mater, the inner meningeal layer, is made of fine blood vessels held together by connective tissue. It’s thin and transparent and clings to the brain and spinal cord surfaces, carrying branches of the cerebral arteries deep into the brain’s fissures and sulci.

The pyramidal system (corticospinal tract) is responsible for fine, skilled movements of skeletal muscle. An impulse in this system originates

in the frontal lobe’s motor cortex and travels downward to the pyramids of the medulla, where it crosses to the opposite side of the spinal cord.

The extrapyramidal system (extracorticospinal tract) controls gross motor movements. An impulse traveling in this system originates in the frontal lobe’s motor cortex and is mediated by basal ganglia, the thalamus, cerebellum, and reticular formation before descending to the spinal cord.

|

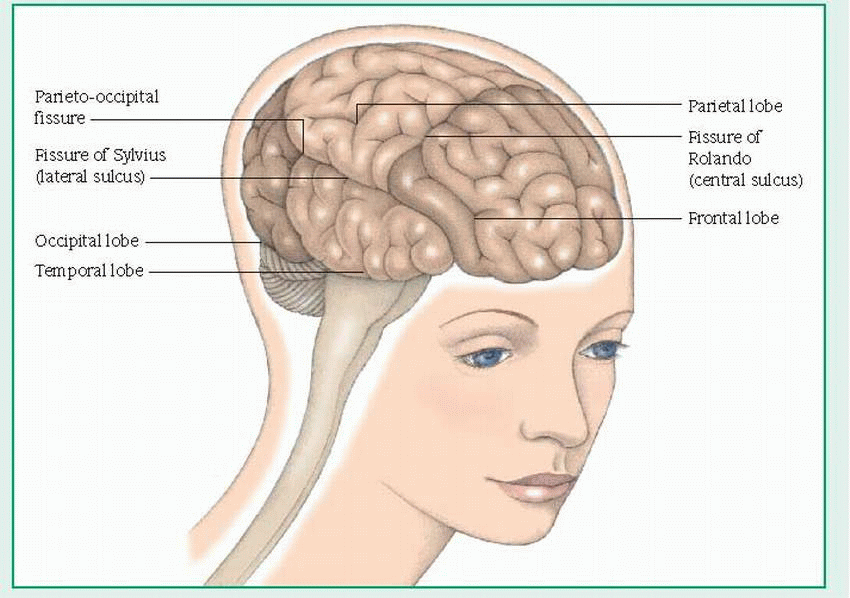

The frontal lobe controls voluntary muscle movements and contains motor areas (including the motor area for speech, or Broca’s area). It’s the center for personality, behavioral, and intellectual functions, such as judgment, memory, and problem solving; for autonomic functions; and for cardiac and emotional responses.

The temporal lobe is the center for taste, hearing, and smell; in the brain’s dominant hemisphere, it interprets spoken language.

The parietal lobe coordinates and interprets sensory information from the opposite side of the body.

The occipital lobe interprets visual stimuli.

8 cervical: C1 to C8

12 thoracic: T1 to T12

5 lumbar: L1 to L5

5 sacral: S1 to S5

1 coccygeal.

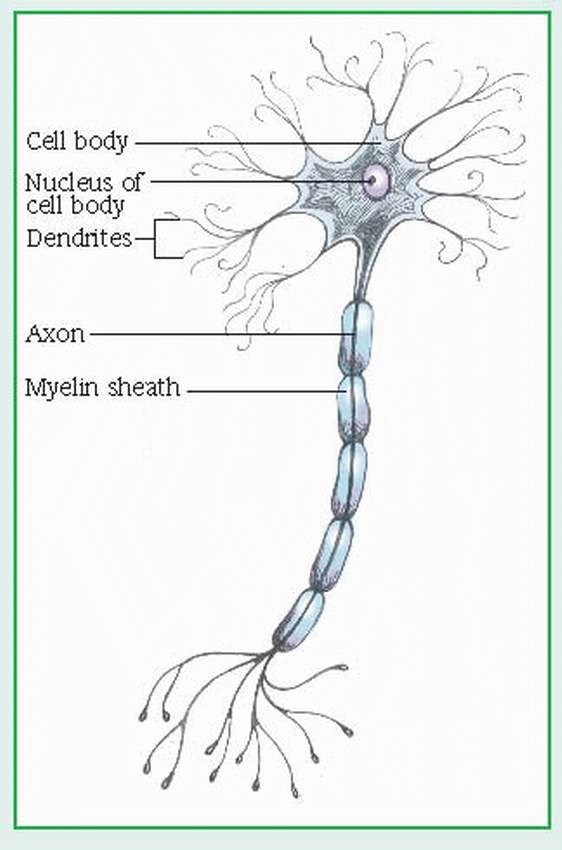

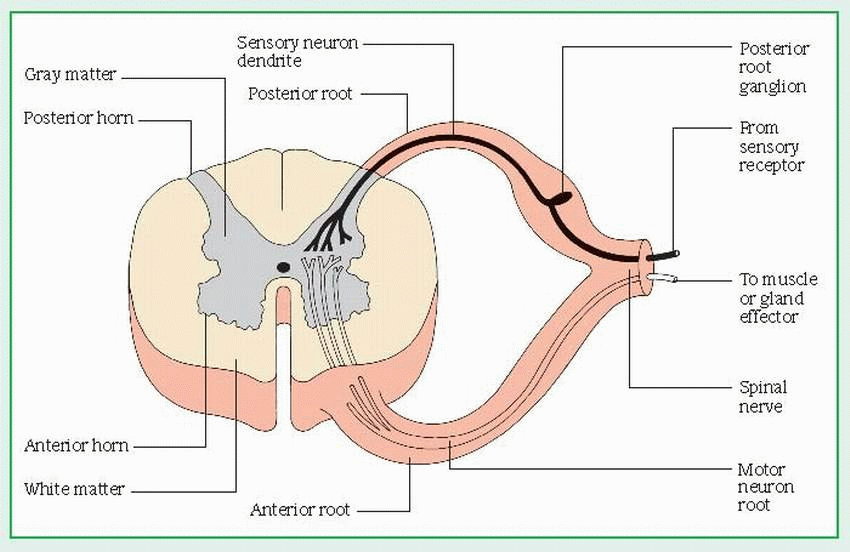

The anterior, or ventral, root consists of motor fibers that relay impulses from the cord to glands and muscles.

The posterior, or dorsal, root consists of sensory fibers that relay sensory information from receptors to the cord. The posterior root has an enlarged area — the posterior root ganglion — which is made up of sensory neuron cell bodies.

The somatic (voluntary) nervous system is activated by will but can also function independently. It’s responsible for all conscious and higher mental processes and for subconscious and reflex actions such as shivering.

The autonomic (involuntary) nervous system regulates unconscious processes to control involuntary body functions, such as digestion, respiration, and cardiovascular function. It’s usually divided into two competing systems: The sympathetic nervous system controls energy expenditure, especially in stressful situations, by releasing adrenergic catecholamines. The parasympathetic nervous system helps conserve energy by releasing the cholinergic neurohormone acetylcholine. These systems balance each other to support homeostasis under normal conditions.

Patient history: In addition to the usual information, try to elicit the patient’s and his family’s perception of the disorder. Use the patient interview to make observations that help evaluate mental status and behavior.

Physical examination: Pay particular attention to obvious abnormalities that may signal serious neurologic problems; for example, fluid draining from the nose or ears. Check for these significant symptoms:

headaches, especially if they’re more severe in the morning, wake the patient, or the pain is unusually intense

change in visual acuity, especially sudden change

numbness or tingling in one or more extremities

clumsiness or complete loss of function in an extremity

mood swings or personality changes

any new onset of seizures or change in seizure activity.

Neurologic examination: Determine cerebral, cerebellar, motor, sensory, and cranial nerve function.

Ask the patient to touch his nose with each index finger, alternating hands. Repeat this test with his eyes closed.

Instruct the patient to tap the index finger and thumb of each hand together rapidly.

Have the patient draw a figure eight in the air with his foot.

To test tandem walk, ask the patient to walk heel to toe in a straight line.

To test balance, perform the Romberg test: Ask the patient to stand with feet together, eyes closed, and arms outstretched without losing balance.

To check gait, ask the patient to walk while you observe posture, balance, and coordination of leg movement and arm swing.

To check muscle tone, palpate muscles at rest and in response to passive flexion. Look for flaccidity, spasticity, and rigidity. Measure muscle size, and look for involuntary movements, such as rapid jerks, tremors, or contractions.

To evaluate muscle strength, have the patient grip your hands and squeeze. Then ask him to push against your palm with his foot. Compare muscle strength on each side, using a 5-point scale (5 is normal strength, 0 is complete paralysis). Also test the patient’s ability to extend and flex the neck, elbows, wrists, fingers, toes, hips, and knees; to extend the spine; to contract and relax the abdominal muscles; and to rotate the shoulders.

Rate reflexes on a 4-point scale (4 is clonus, 0 is absent reflex). Before testing reflexes, make sure that the patient is comfortable and relaxed. Then, to test superficial reflexes, stroke the skin of the abdominal, gluteal, plantar, and scrotal

regions with a moderately sharp object that won’t puncture the skin. (Don’t use the same pin to test another patient.) A normal response to this stimulus is flexion. To test deep reflexes, use a reflex hammer to briskly tap the biceps, the triceps, and the brachioradialis, patellar, and Achilles tendon regions. A normal response is rapid extension and contraction.

Test | Patient’s reaction | Score |

Best eye opening response | Open spontaneously Open to verbal command Open to pain No response | 4 3 2 1 |

Best motor response | Obeys verbal command Localizes painful stimuli Flexion-withdrawal Flexion-abnormal (decorticate rigidity) Extension (decerebrate rigidity) No response | 6 5 4 3 2 1 |

Best verbal response | Oriented and converses Disoriented and converses Inappropriate words Incomprehensible sounds No response | 5 4 3 2 1 |

Total | 3 to 15 |

Superficial pain perception: Lightly press the point of an open safety pin against the patient’s skin. Don’t press hard enough to scratch the skin. Discard pin after use.

Thermal sensitivity: The patient tells what he feels when you place a test tube filled with hot water and one filled with cold water against his skin.

Tactile sensitivity: Ask the patient to close his eyes and tell you what he feels when touched lightly on hands, wrists, arms, thighs, lower legs, feet, and trunk with a wisp of cotton.

Sensitivity to vibration: Place the base of a vibrating tuning fork against the patient’s wrists, elbows, knees, or other bony prominences. Hold it in place, and ask the patient to tell you when it stops vibrating.

Position sense: Hold the lateral medial portion of the patient’s fingers and toes and move them up, down, and to the side. Ask the patient to tell you the direction of movement.

Discriminatory sensation: Ask the patient to close his eyes and identify familiar textures (velvet or burlap) or objects placed in his hand or numbers and letters traced on his palm.

Two-point discrimination: Using calipers or other sharp objects, touch the patient in two different places simultaneously. Ask if he can feel one or two points. Record how many millimeters of separation are required for the patient to feel two points.

Olfactory nerve (I): Have the patient close his eyes and, using each nostril separately, try to identify common nonirritating smells, such as cinnamon, coffee, or peppermint.

Optic nerve (II): Examine the patient’s eyes with an ophthalmoscope, and have him read a Snellen eye chart or a newspaper. To test peripheral vision, ask him to cover one eye and fix his other eye on a point directly in front of him. Then, ask if he can see you wiggle your finger in the four quadrants; you’d expect him to see your finger in all four.

Oculomotor nerve (III): Compare the size and shape of the patient’s pupils and the equality of pupillary response to a small light in a darkened room. Shine the light from a lateral position, not directly in front of the patient’s eyes.

Trochlear nerve (IV) and abducens nerve (VI): To assess for conjugate and lateral eye movement, ask the patient to follow your finger with his eyes as you slowly move it from his far left to his far right.

Trigeminal nerve (V): To test all three portions of this cranial nerve, test facial sensation by stroking the patient’s jaws, cheeks, and forehead with a cotton swab, the point of a pin, or test tubes filled with hot or cold water. Because testing for a blink reflex is irritating to the patient, it’s not commonly done. If you must test for this response (it may be decreased in patients who wear contact lenses), touch the cornea lightly with a wisp of cotton or tissue, and avoid repeating the test, if possible. To test for jaw jerk, ask the patient to hold his mouth slightly open; then tap the middle of his chin lightly with a reflex hammer. The jaw should jerk closed.

Facial nerve (VII): To test upper and lower facial motor function, ask the patient to raise his eyebrows, close his eyes, wrinkle his forehead, and show his teeth. To test sense of taste, ask him to identify the taste of salty, sour, sweet, and bitter substances, which you have placed on his tongue.

Acoustic nerve (VIII): Ask the patient to identify common sounds such as a ticking clock. With a tuning fork, test for air and bone conduction.

Glossopharyngeal nerve (IX): To test gag reflex, touch a tongue blade to each side of the patient’s pharynx.

Vagus nerve (X): Observe ability to swallow, and watch for symmetrical movements of soft palate when the patient says, “Ah.”

Spinal accessory nerve (XI): To test shoulder muscle strength, palpate the patient’s shoulders, and ask him to shrug against a resistance.

Hypoglossal nerve (XII): To test tongue movement, ask the patient to stick out his tongue. Inspect it for tremor, atrophy, or lateral deviation. To test for strength, ask the patient to move his tongue from side to side while you hold a tongue blade against it.

Skull X-ray identifies skull malformations, fractures, erosion, or thickening. Changes in landmarks may indicate a space-occupying lesion.

Computed tomography (CT) scan produces three-dimensional images that can identify hemorrhage, intracranial tumors, malformation, and cerebral atrophy, edema, calcification, and infarction. If a contrast medium is used, the procedure is invasive.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) views the CNS in greater detail than a CT scan and is the procedure of choice for detecting multiple sclerosis; intraluminal clots and blood flow in arteriovenous malformations and aneurysms; brain stem, posterior fossa, and spinal cord lesions; early cerebral infarction; and brain tumors. A noniodinated contrast medium may be used to enhance lesions. Advances in MRI allow visualization of cerebral arteries and venous sinuses without administration of a contrast medium.

EEG detects abnormal electrical activity in the brain (for example, from a seizure, metabolic disorder, or drug overdose).

Ultrasonography detects carotid lesions or changes in carotid blood flow and velocity. High-frequency sound waves reflect back the velocity of blood flow, which is then reported as a graphic recording of a waveform.

Evoked potentials evaluate the visual, auditory, and somatosensory nerve pathways by measuring the brain’s electrical response to stimulation of the sensory organs or peripheral nerves.

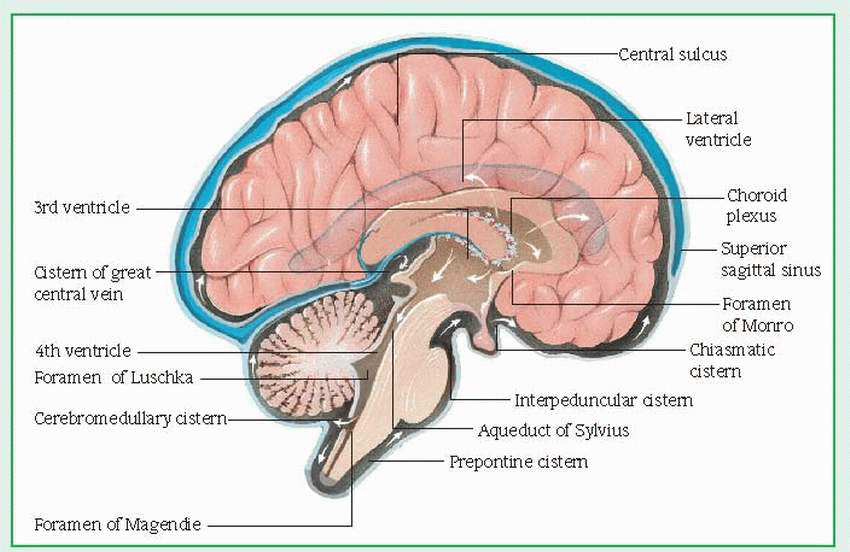

In lumbar puncture, a needle is inserted into the subarachnoid space of the spinal cord,

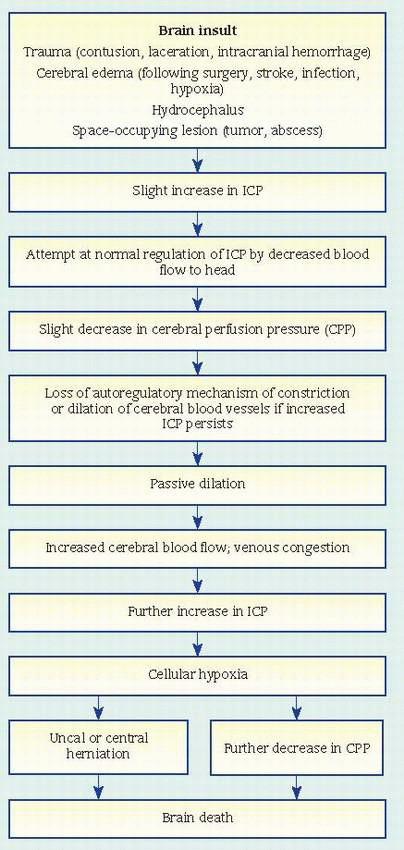

usually between L3 and L4 (or L4 and L5). This allows aspiration of CSF for analysis to detect infection or hemorrhage; to determine cell count and glucose, protein, and globulin levels; and to measure CSF pressure. Lumbar puncture is usually contraindicated in hydrocephalus and in increased intracranial pressure (ICP) because a quick pressure reduction may cause brain herniation. (See What happens in increased ICP.)

limiting blood flow to the head

displacing CSF into the spinal canal

increasing absorption or decreasing production of CSF — withdrawing water from brain tissue into the blood and excreting it through the kidneys. When compensatory mechanisms become overworked, small changes in volume lead to large changes in pressure.

|

Myelography follows a lumbar puncture and CSF removal. In this procedure, a radiologic dye is instilled and X-rays show spinal abnormalities and determine spinal cord compression related to back pain or extremity weakness.

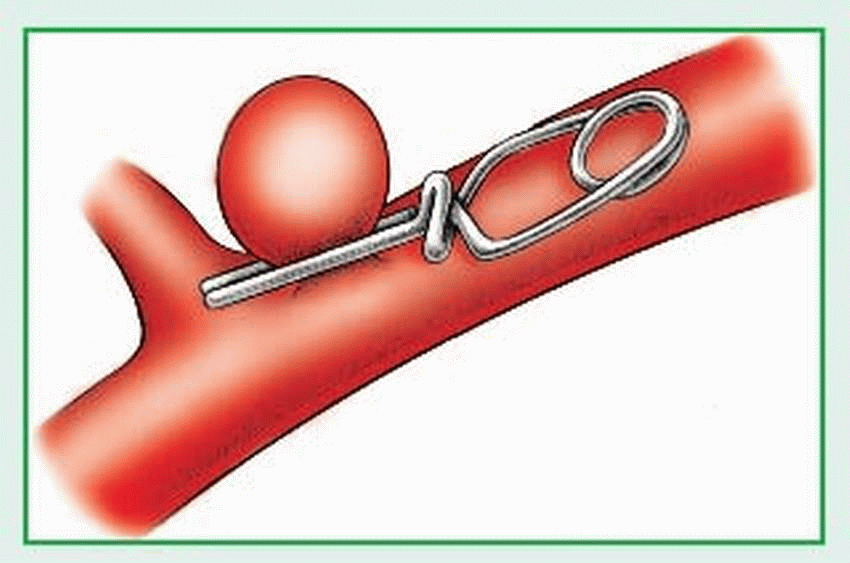

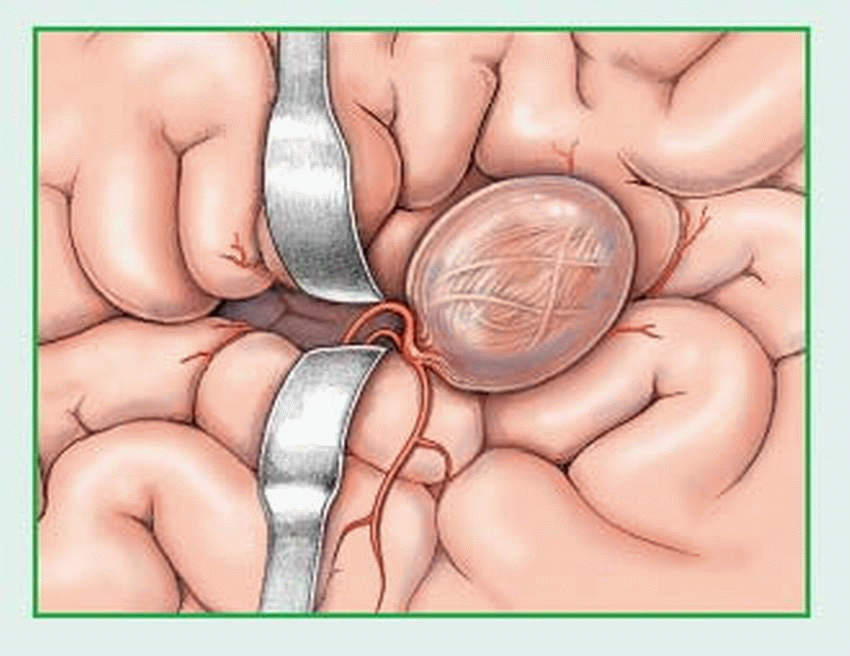

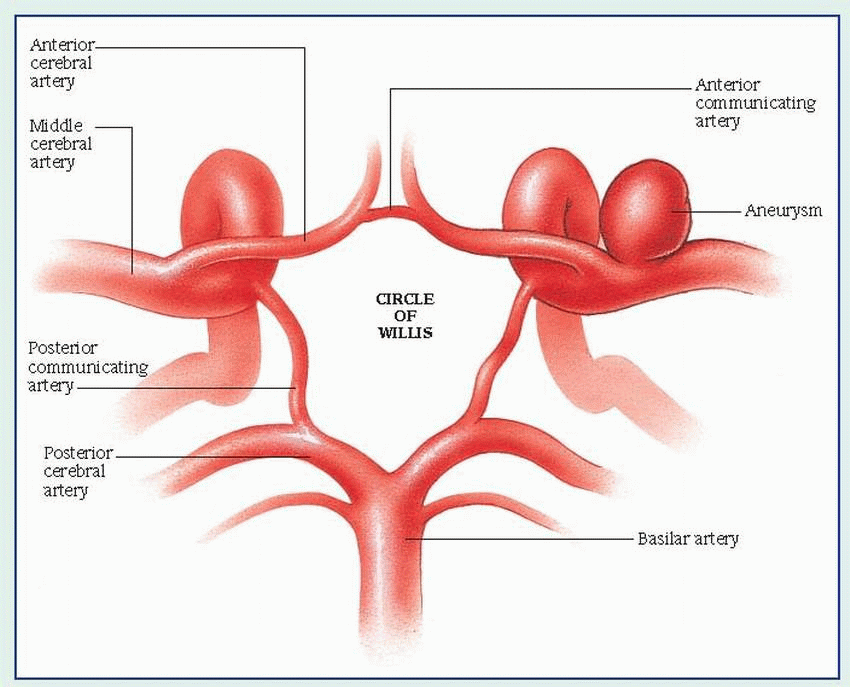

In cerebral arteriography, also known as angiography, a catheter is inserted into an artery — usually the femoral artery — and is threaded up to the carotid artery. Then a radiopaque dye is injected, allowing X-ray visualization of the cerebral vasculature. Sometimes the catheter is threaded directly into the brachial or carotid artery. This test can show cerebrovascular abnormalities and spasms plus arterial changes due to a tumor, arteriosclerosis, hemorrhage, an aneurysm, or blockage. A patient undergoing this procedure is at risk for a stroke and for increased ICP.

Digital subtraction angiography visualizes cerebral vessels using contrast medium administered I.V., after which computer-assisted precontrast and postcontrast images are compared. The first image is “subtracted” from the second, which highlights the cerebral vessels.

Brain scan measures gamma rays produced by a radioisotope injected I.V. Uptake and distribution of the isotope in the brain highlights intracranial masses, vascular lesions, and other problems.

ICP monitoring can be a direct, invasive method of identifying trends in ICP. A subarachnoid screw and an intraventricular catheter convert CSF pressure readings into waveforms that are displayed digitally on an oscilloscope monitor. Another method uses a fiber-optic catheter inserted in the subdural space; with this indirect method, pressure changes are reported digitally or in waveform.

Electromyography detects lower motor neuron disorders, neuromuscular disorders, and nerve damage. A needle inserted into selected muscles at rest and during voluntary contraction picks up nerve impulses and measures nerve conduction time.

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy provides a measure of brain chemistry. It can be used to monitor biochemical changes in tumors, epilepsy, metabolic disorders, infection, and neurodegenerative diseases.

Seizure disorder

Injuries from falls

Speech, vision, and hearing problems

Language and perception deficits

Respiratory problems (poor swallowing and gag reflexes)

Dental problems

Mental retardation

legs; involuntary facial movements may make speech difficult. These athetoid movements become more severe during stress, decrease with relaxation, and disappear entirely during sleep.

has difficulty sucking or keeping the nipple or food in his mouth

seldom moves voluntarily or has arm or leg tremors with voluntary movement

crosses his legs when lifted from behind rather than pulling them up or “bicycling” like a normal infant

has legs that are difficult to separate, making diaper changing difficult

persistently uses only one hand or, as he gets older, uses hands well but not legs.

Prenatal conditions that may increase risk of CP: maternal infection (especially rubella), maternal drug ingestion, radiation, anoxia, toxemia, maternal diabetes, abnormal placental attachment, malnutrition, and isoimmunization

Perinatal and birth difficulties that increase the risk of CP: forceps delivery, breech presentation, placenta previa, abruptio placentae, metabolic or electrolyte disturbances, abnormal maternal vital signs from general or spinal anesthetic, prolapsed cord with delay in delivery of head, premature birth, prolonged or unusually rapid labor, and multiple birth (especially infants born last in a multiple birth)

Infection or trauma during infancy: poisoning, severe kernicterus resulting from erythroblastosis fetalis, brain infection, head trauma, prolonged anoxia, brain tumor, cerebral circulatory anomalies causing blood vessel rupture, and systemic disease resulting in cerebral thrombosis or embolus

Braces or splints and special appliances, such as adapted eating utensils and a low toilet seat with arms, help these children perform activities independently.

An artificial urinary sphincter may be indicated for the incontinent child who can use the hand controls.

Range-of-motion stretches minimize contractures.

Orthopedic surgery may be indicated to correct contractures. Botulinum toxin has been shown to reduce or delay the need for surgery.

Phenytoin, phenobarbital, or another anticonvulsant may be used to control seizures.

Muscle relaxants or neurosurgery may be required to decrease spasticity.

A child with CP may be hospitalized for orthopedic surgery or for treatment of other complications.

Speak slowly and distinctly. Encourage the child to ask for things he wants. Listen patiently and don’t rush him.

Plan a high-calorie diet that’s adequate to meet the child’s high-energy needs.

During meals, maintain a quiet, unhurried atmosphere with as few distractions as possible. The child should be encouraged to feed himself and may need special utensils and a chair with a solid footrest. Teach him to place food far back in his mouth to facilitate swallowing.

Encourage the child to chew food thoroughly, drink through a straw, and suck on lollipops to develop the muscle control needed to minimize drooling.

Allow the child to wash and dress independently, assisting only as needed. The child may need clothing modifications.

Give all care in an unhurried manner; otherwise, muscle spasticity may increase.

Encourage the child and his family to participate in the plan of care so they can continue it at home.

Care for associated hearing or visual disturbances, as necessary.

Give frequent mouth care and dental care, as necessary.

Reduce muscle spasms that increase postoperative pain by moving and turning the child carefully after surgery; provide analgesics as needed.

After orthopedic surgery, provide cast care. Reposition the child often, check for foul odor, and ventilate under the cast with a cool air blow-dryer. Use a flashlight to check for skin breakdown beneath the cast. Help the child relax, perhaps by giving a warm bath, before reapplying a bivalved cast.

Encourage them to set realistic individual goals.

Assist in planning crafts and other activities.

Stress the child’s need to develop peer relationships; warn the parents against being overprotective.

Identify and deal with family stress. The parents may feel unreasonable guilt about their child’s handicap and may need psychological counseling.

Refer the parents to supportive community organizations. For more information, tell them to contact the United Cerebral Palsy Association or their local chapter.

Mental retardation

Impaired motor function

Vision loss

Death

include widening and bulging of the fontanels; distended scalp veins; thin, shiny, and fragile-looking scalp skin; and underdeveloped neck muscles. In severe hydrocephalus, the roof of the orbit is depressed, the eyes are displaced downward, and the sclerae are prominent. Sclera seen above the iris is called the setting-sun sign. A high-pitched, shrill cry; abnormal muscle tone of the legs; irritability; anorexia; and projectile vomiting commonly occur. In adults and older children, indicators of hydrocephalus include decreased level of consciousness (LOC), ataxia, incontinence, loss of coordination, and impaired intellect.

|

procedure is insertion of a ventriculoatrial shunt, which drains fluid from the brain’s lateral ventricle into the right atrium of the heart, where the fluid makes its way into the venous circulation.

On initial assessment, obtain a complete history from the patient or his family. Note general behavior, especially irritability, apathy, or decreased LOC. Perform a neurologic assessment. Examine the eyes: pupils should be equal and reactive to light. In adults and older children, evaluate movements and motor strength in extremities. Watch especially for ataxia, confusion, and incontinence. Ask the patient if he has headaches, and watch for projectile vomiting; both are signs of increased ICP. Also watch for seizures. Note changes in vital signs.

Encourage maternal-infant bonding when possible. When caring for the infant yourself, hold him on your lap for feeding; stroke and cuddle him, and speak soothingly.

Check fontanels for tension or fullness, and measure and record head circumference. On the patient’s chart, draw a picture showing where to measure the head so that other staff members measure it in the same place, or mark the forehead with ink.

To prevent postfeeding aspiration and hypostatic pneumonia, place the infant on his side and reposition every 2 hours, or prop him up in an infant seat.

To prevent skin breakdown, make sure his earlobe is flat, and place a sheepskin or rubber foam under his head.

When turning the infant, move his head, neck, and shoulders with his body to reduce strain on his neck.

Feed the infant slowly. To lessen strain from the weight of the infant’s head on your arm while holding him during feeding, place his head, neck, and shoulders on a pillow.

Place the infant on the side opposite the operative site with his head level with his body unless the physician’s orders specify otherwise.

Check temperature, pulse rate, blood pressure, and LOC. Also check fontanels for fullness daily. Watch for vomiting, which may be an early sign of increased ICP and shunt malfunction.

Watch for signs of infection, especially meningitis: fever, stiff neck, irritability, or tense fontanels. Also watch for redness, swelling, or other signs of local infection over the shunt tract. Check dressing often for drainage.

Listen for bowel sounds after ventriculoperitoneal shunt.

Check the infant’s growth and development periodically, and help the parents set goals consistent with ability and potential. Help parents focus on their child’s strengths, not his weaknesses. Discuss special education programs, and emphasize the infant’s need for sensory stimulation appropriate for his age. Teach parents to watch for signs of shunt malfunction, infection, and paralytic ileus. Tell them that surgery for lengthening the shunt will be required periodically as the child grows older. Surgery may also be required to correct shunt malfunctioning or to treat infection. Emphasize that hydrocephalus is a lifelong problem and that the child will require regular, continuing evaluation.

|

Subarachnoid hemorrhage Brain-tissue infarction Rebleeding

Meningeal irritation

Hydrocephalus

Grade I (minimal bleed): Patient is alert with no neurologic deficit; he may have a slight headache and nuchal rigidity.

Grade II (mild bleed): Patient is alert, with a mild to severe headache, nuchal rigidity and, possibly, third-nerve palsy.

Grade III (moderate bleed): Patient is confused or drowsy, with nuchal rigidity and, possibly, a mild focal deficit.

Grade IV (severe bleed): Patient is stuporous, with nuchal rigidity and, possibly, mild to severe hemiparesis.

Grade V (moribund; commonly fatal): If nonfatal, patient is in deep coma or decerebrate.

Death from increased ICP: Increased ICP may push the brain downward, impair brain stem function, and cut off blood supply to the part of the brain that supports vital functions.

Rebleed: Generally, after the initial bleeding episode, a clot forms and seals the rupture, which reinforces the wall of the aneurysm for 7 to 10 days. However, after the 7th day, fibrinolysis begins to dissolve the clot and increases the risk of rebleeding. Signs and symptoms are similar to those accompanying the initial hemorrhage. Rebleeds during the first 24 hours after initial hemorrhage aren’t uncommon, and they contribute to cerebral aneurysm’s high mortality.

Vasospasm: Why this occurs isn’t clearly understood. Usually, vasospasm occurs in blood vessels adjacent to the cerebral aneurysm, but it may extend to major vessels of the brain, causing ischemia and altered brain function.

(fasudil hydrochloride and colforsin daropate) are under investigation.

careful control of blood pressure (Calcium antagonists are preferred.)

bed rest and avoidance of head-down position

avoidance of stimulants, including caffeine and catecholamines

avoidance of platelet inhibitors such as aspirin

corticosteroids (sometimes used to decrease edema but studies are not conclusive)

anticonvulsants

sedatives.

An accurate neurologic assessment, good patient care, patient and family teaching, and psychological support can speed recovery and reduce complications.

During initial treatment after hemorrhage, establish and maintain a patent airway if the patient needs supplementary oxygen. Position the patient to promote pulmonary drainage and prevent upper airway obstruction. If he’s intubated, administering 100% oxygen before suctioning to remove secretions will prevent hypoxia and vasodilation from carbon dioxide accumulation. Suction no longer than 20 seconds to avoid increased ICP. Give frequent nose and mouth care.

Impose aneurysm precautions to minimize the risk of rebleed and to avoid increased ICP. Such precautions include bed rest in a quiet, darkened room (keep the head of the bed flat or under 30 degrees, as ordered); limited visitors; avoiding strenuous physical activity and straining with bowel movements; and restricted fluid intake. Be sure to explain why these restrictive measures are necessary.

Turn the patient often. Encourage occasional deep breathing and leg movement. Warn the patient to avoid all unnecessary physical

activity. Assist with active range-of-motion exercises; if the patient is paralyzed, perform regular passive range-of-motion exercises.

Monitor ABG levels, LOC, and vital signs often, and accurately measure intake and output. Avoid taking temperature rectally because vagus nerve stimulation may cause cardiac arrest.

Watch for these danger signals, which may indicate an enlarging aneurysm, rebleeding, intracranial clot, vasospasm, or other complication: decreased LOC, unilateral enlarged pupil, onset or worsening of hemiparesis or motor deficit, increased blood pressure, slowed pulse, worsening of headache or sudden onset of a headache, renewed or worsened nuchal rigidity, and renewed or persistent vomiting. Intermittent signs such as restlessness, extremity weakness, and speech alterations can also indicate increasing ICP.

Give fluids as ordered, and monitor I.V. infusions to avoid increased ICP.

If the patient has facial weakness, assess the gag reflex and assist him during meals, placing food in the unaffected side of his mouth. If he can’t swallow, insert a nasogastric tube as ordered, and give all tube feedings slowly. Prevent skin breakdown by taping the tube so it doesn’t press against the nostril. If the patient can eat, provide a high-fiber diet to prevent straining at stool, which can increase ICP. Obtain an order for a stool softener, such as dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate, or a mild laxative, and administer as ordered. Don’t force fluids. Implement a bowel program based on previous habits. If the patient is receiving steroids, check the stool for blood.

With third or facial nerve palsy, administer artificial tears or ointment to the affected eye, and tape the eye shut at night to prevent corneal damage.

To minimize stress, encourage relaxation techniques. If possible, avoid using restraints because these can cause agitation and raise ICP.

Administer antihypertensives as indicated. Carefully monitor blood pressure and immediately report any significant change, but especially a rise in systolic pressure.

Prevent deep vein thrombosis by applying antiembolism stockings or sequential compression sleeves.

If the patient can’t speak, establish a simple means of communication, or use cards or a notepad. Try to limit conversation to topics that won’t frustrate the patient. Encourage his family to speak to him in a normal tone, even if he doesn’t seem to respond.

Provide emotional support, and include the patient’s family in his care as much as possible. Encourage family members to adopt a realistic attitude, but don’t discourage hope.

Before discharge, make a referral to a visiting nurse or a rehabilitation center when necessary, and teach the patient and his family how to recognize signs of rebleeding.

rupture — causing hemorrhage into the brain or subarachnoid space.

Aneurysm and subsequent rupture

Intracerebral, subarachnoid, or subdural hemorrhage

Hydrocephalus

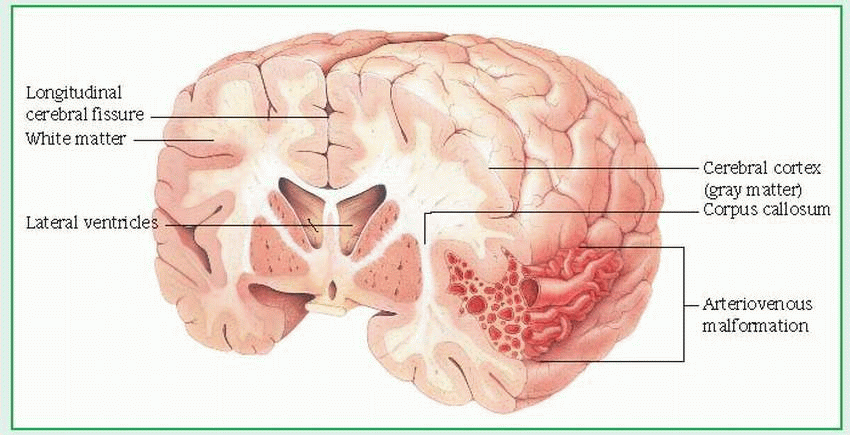

cerebral AVM. In some cases, symptoms may also occur due to lack of blood flow to an area of the brain (ischemia), compression or distortion of brain tissue by large AVMs, or abnormal brain development in the area of the malformation. Progressive loss of nerve cells in the brain may occur, caused by mechanical (pressure) and ischemic (lack of blood supply) factors.

Monitor vital signs and adjust medications to control hypertension.

Monitor neurologic status.

Monitor for seizure activity and institute seizure precautions.

Maintain a quiet atmosphere and provide relaxation techniques.

Discuss the importance of reporting any signs of intracranial bleeding immediately (sudden severe headache, vision changes, decreased movement in extremities, and change in LOC).

Refer to social service for support services if neurologic deficits have occurred from a ruptured AVM.

and tumor, intracranial bleeding, abscess, or aneurysm.

Worsening of preexisting hypertension

Photophobia

Emotional lability

Motor weakness

Headaches seldom require hospitalization unless caused by a serious disorder. If that’s the case, direct your care to the underlying problem.

Obtain a complete patient history: duration and location of the headache; time of day it usually begins; nature of the pain; concurrence with other symptoms such as blurred vision;

precipitating factors, such as tension, menstruation, loud noises, menopause, or alcohol; medications taken such as oral contraceptives; or prolonged fasting. Exacerbating factors can also be assessed through ongoing observation of the patient’s personality, habits, activities of daily living, family relationships, coping mechanisms, and relaxation activities.

Clinical features of migraine headaches

Type

Signs and symptoms

Common migraine (most prevalent)

Usually occurs on weekends and holidays

▪ Prodromal symptoms (fatigue, nausea, vomiting, and fluid imbalance) precede headache by about 1 day.

▪ Sensitivity to light and noise (most prominent feature)

▪ Headache pain (unilateral or bilateral, aching or throbbing)

Classic migraine

Usually occurs in compulsive personalities and within families

▪ Prodromal symptoms include visual disturbances, such as zigzag lines and bright lights (most common), sensory disturbances (tingling of face, lips, and hands), or motor disturbances (staggering gait).

▪ Recurrent and periodic headaches

Hemiplegic and ophthalmoplegic migraine (rare)

Usually occurs in young adults

▪ Severe, unilateral pain

▪ Extraocular muscle palsies (involving third cranial nerve) and ptosis

▪ With repeated headaches, possible permanent third cranial nerve injury

▪ In hemiplegic migraine, neurologic deficits (hemiparesis, hemiplegia) may persist after the headache subsides.

Basilar artery migraine

Occurs in young women before their menstrual periods

▪ Prodromal symptoms usually include partial vision loss followed by vertigo, ataxia, dysarthria, tinnitus and, sometimes, tingling of the fingers and toes, lasting from several minutes to almost an hour.

▪ Headache pain, severe occipital throbbing, vomiting

Cluster headaches

Occur in men more commonly than women and occur at all ages, but more commonly in adolescents and middle-age people

▪ Episodic type (more common) and involves one to three short-lived attacks of periorbital pain per day over a 4- to 8-week period followed by a pain-free interval averaging 1 year. Chronic type occurs after an episodic pattern is established.

▪ Unilateral pain occurs without warning, reaching a crescendo within 5 minutes, and is described as excruciating and deep, with attacks lasting from 30 minutes to 2 hours.

▪ Associated symptoms may include tearing, reddening of the eye, nasal stuffiness, lid ptosis, and nausea.

Using the history as a guide, help the patient avoid exacerbating factors. Advise him to lie down in a dark, quiet room during an attack and to place ice packs on his forehead or a cold cloth over his eyes.

Instruct the patient to take the prescribed medication at the onset of migraine symptoms, to prevent dehydration by drinking plenty of fluids after nausea and vomiting subside, and to use other headache relief measures.

The patient with a migraine headache usually needs to be hospitalized only if nausea and vomiting are severe enough to induce dehydration and possible shock.

Avoid repeated use of narcotics if possible.

get adequate sleep

eat a well-balanced diet and drink plenty of water

do upper-body stretching exercises

quit smoking

learn relaxation techniques such as yoga, medication, and deep breathing

avoid known causative triggers.

birth trauma (inadequate oxygen supply to the brain, blood incompatibility, or hemorrhage)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree