Obstetric and Gynecologic Disorders

INTRODUCTION

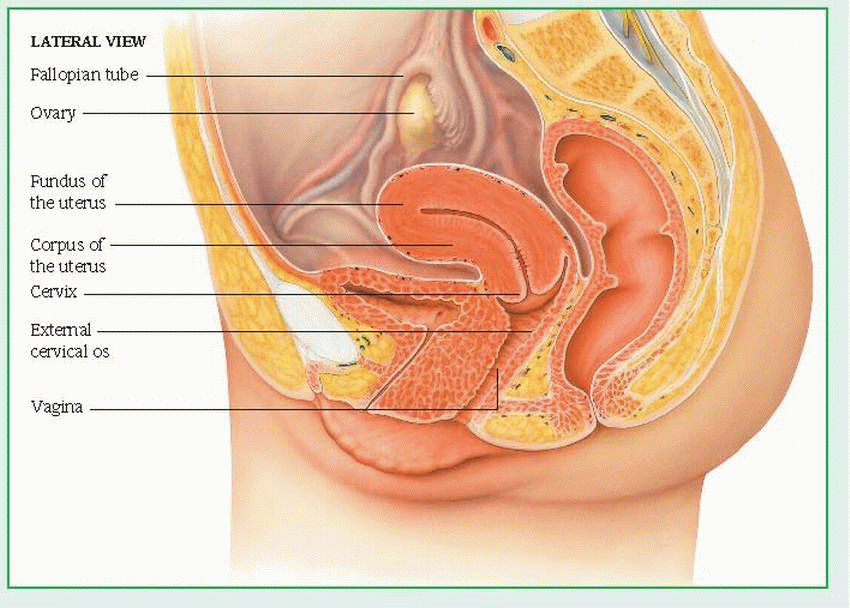

Medical care of the obstetric or gynecologic patient reflects a growing interest in improving the quality of health care for women. Skills are needed to assess, counsel, teach, and refer patients, while weighing such relevant factors as the patient’s desire to have children, sexual adjustment problems, and self-image. Often, this care is complicated by multiple obstetric and gynecologic abnormalities occurring simultaneously. For example, a patient with dysmenorrhea may also have trichomonal vaginitis, dysuria, and unsuspected infertility. Her condition may be further complicated by associated urologic disorders, due to the proximity of the urinary and reproductive systems. This tendency for multiple and complex disorders is readily understandable upon review of the female genitalia’s anatomic structure. (See External and internal female genitalia.)

EXTERNAL STRUCTURES

Female genitalia include the following external structures, collectively known as the vulva: mons pubis (or mons veneris), labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, and the vestibule. The perineum is the external region between the vulva and the anus. The size, shape, and color of these structures—as well as pubic hair distribution and skin texture and pigmentation—vary greatly among individuals. Furthermore, these external structures undergo distinct changes during the life cycle.

The mons pubis is the pad of fat over the symphysis pubis (pubic bone), which is usually covered by the base of the inverted triangular patch of pubic hair that grows over the vulva after puberty.

The labia majora are the two thick, longitudinal folds of fatty tissue that extend from the mons pubis to the posterior aspect of the perineum. The labia majora protect the perineum and contain large sebaceous glands that help maintain lubrication. Virtually absent in the young child, their development is a characteristic sign of puberty’s onset. The skin of the more prominent parts of the labia majora is pigmented and darkens after puberty.

The labia minora are the two thin, longitudinal folds of skin that border the vestibule. Firmer than the labia majora, they extend from the clitoris to the fourchette.

The clitoris is the small, protuberant organ located just beneath the arch of the mons pubis. The clitoris contains erectile tissue, venous cavernous spaces, and specialized sensory corpuscles that are stimulated during coitus.

The vestibule is the oval space bordered by the clitoris, labia minora, and fourchette. The urethral meatus is located in the anterior portion of the vestibule; the vaginal meatus, in the posterior portion. The hymen is the elastic membrane that partially obstructs the vaginal meatus in virgins.

Several glands lubricate the vestibule. Skene’s glands open on both sides of the urethral meatus; Bartholin’s glands, on both sides of the vaginal meatus.

The fourchette is the posterior junction of the labia majora and labia minora. The perineum, which includes the underlying muscles and fascia, is the external surface of the floor of the pelvis, extending from the fourchette to the anus.

INTERNAL STRUCTURES

The following internal structures are included in the female genitalia: vagina, cervix, uterus, fallopian tubes (or oviducts), and ovaries.

The vagina occupies the space between the bladder and the rectum. A muscular, membranous tube that’s about 3” (7.5 cm) long, the vagina connects the uterus and the vestibule of the external genitalia. It serves as a passageway for sperm to the fallopian tubes, for the discharge of menstrual fluid, and for childbirth.

The cervix, or neck of the uterus, protrudes at least 3/4” (2 cm) into the proximal end of the vagina. A rounded, conical structure, the cervix joins the uterus and the vagina at a 45- to 90-degree angle.

The uterus is the hollow, pear-shaped organ in which the conceptus grows during pregnancy. The part of the uterus above the junction of the fallopian tubes is called the fundus; the part below this junction is called the corpus The junction of the corpus and cervix forms the lower uterine segment.

The thick uterine wall consists of mucosal, muscular, and serous layers. The inner mucosal lining—the endometrium—undergoes cyclic changes to facilitate and maintain pregnancy.

The smooth muscular middle layer—the myometrium—interlaces the uterine and ovarian arteries and veins that circulate blood through the uterus. During pregnancy, this vascular system expands dramatically. After abortion or childbirth, the myometrium contracts to constrict the vasculature and control blood loss.

The outer serous layer—the parietal peritoneum—covers all of the fundus, part of the corpus, but none of the cervix. This incompleteness allows surgical entry into the uterus without

incision of the peritoneum, thereby reducing the risk of peritonitis.

incision of the peritoneum, thereby reducing the risk of peritonitis.

The fallopian tubes extend from the sides of the fundus and terminate near the ovaries. Through ciliary and muscular action, these small tubes (31/4” to 51/2” [8 to 14 cm] long) carry ova from the ovaries to the uterus and facilitate the movement of sperm from the uterus toward the ovaries. Fertilization of the ovum normally occurs in a fallopian tube. The same ciliary and muscular action helps move a zygote (fertilized ovum) down to the uterus, where it implants in the blood-rich inner uterine lining, the endometrium.

The ovaries are two almond-shaped organs, one on either side of the fundus, that are situated behind and below the fallopian tubes. The ovaries produce ova and two primary hormones—estrogen and progesterone—in addition to small amounts of androgen. These hormones, in turn, produce and maintain secondary sex characteristics, prepare the uterus for pregnancy, and stimulate mammary gland development.

The ovaries are connected to the uterus by the utero-ovarian ligament and are divided into two parts: the cortex, which contains primor dial and graafian follicles in various stages of development, and the medulla, which consists primarily of vasculature and loose connective tissue.

A normal female is born with at least 400,000 primordial follicles in her ovaries. At puberty, these ova precursors become graafian follicles, in response to the effects of pituitary gonadotropic hormones—follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). In the life cycle of a female, however, less than 500 ova eventually mature and develop the potential for fertilization.

THE MENSTRUAL CYCLE

Maturation of the hypothalamus and the resultant increase in hormone levels initiate puberty. In the young girl, breast development—the first sign of puberty—is followed by the appearance of pubic and axillary hair and the characteristic adolescent growth spurt. The reproductive system begins to undergo a series of hormoneinduced changes that result in menarche, onset of menstruation (or menses). In North American females, menarche usually occurs at about age 13 but may occur between ages 9 and 18. Menstrual periods initially are irregular and

anovulatory, but after a year or so, they become more regular. (See Menstrual cycle.)

anovulatory, but after a year or so, they become more regular. (See Menstrual cycle.)

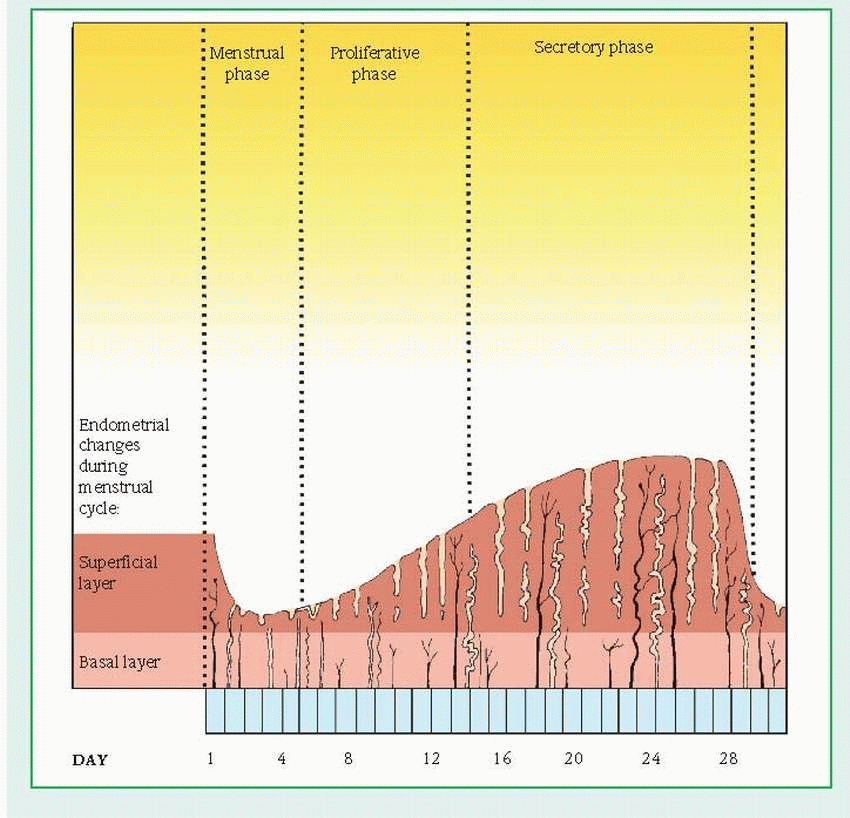

Menstrual cycle

The menstrual cycle is divided into three distinct phases:

The menstrual phase starts on the first day of menstruation. The top layer of the endometrium (the material lining the uterus) breaks down and flows out of the body. This flow, called the menses, consists of blood, mucus, and unneeded tissue.

During the proliferative phase, the endometrium begins to thicken, and the estrogen level in the blood rises.

In the secretory phase, the endometrium continues to thicken to nourish an embryo should fertilization occur. Without fertilization, the top layer of the endometrium breaks down, and the menstrual phase of the cycle begins again.

|

The menstrual cycle consists of three different phases: menstrual, proliferative (estrogendominated), and secretory (progesteronedominated). These phases correspond to the phases of ovarian function. The menstrual and proliferative phases correspond to the follicular ovarian phase; the secretory phase corresponds to the luteal ovarian phase.

The menstrual phase begins with day 1 of menstruation. During this phase, low estrogen and progesterone levels stimulate the hypothalamus to secrete gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH). This substance, in turn, stimulates pituitary secretion of FSH and LH. When the FSH level rises, LH output increases.

The proliferative (follicular) phase lasts from cycle day 6 to day 14. During this phase, LH and FSH act on the ovarian follicle, causing

estrogen secretion, which in turn stimulates the buildup of the endometrium. Late in this phase, estrogen levels peak, FSH secretion declines, and LH secretion increases, surging at midcycle (around day 14). Then estrogen production decreases, the follicle matures, and ovulation occurs.

estrogen secretion, which in turn stimulates the buildup of the endometrium. Late in this phase, estrogen levels peak, FSH secretion declines, and LH secretion increases, surging at midcycle (around day 14). Then estrogen production decreases, the follicle matures, and ovulation occurs.

During the secretory phase, FSH and LH levels drop. Estrogen levels decline initially, then increase along with progesterone levels as the corpus luteum begins functioning. During this phase, the endometrium responds to progesterone stimulation by becoming thick and secretory in preparation for implantation of a fertilized ovum. About 10 to 12 days after ovulation, the corpus luteum begins to diminish, as do estrogen and progesterone levels, until hormone levels are insufficient to sustain the endometrium in a fully developed secretory state. Then the endometrial lining is shed (menses). Subsequently decreasing estrogen and progesterone levels stimulate the hypothalamus to produce Gn-RH, which in turn begins the cycle again.

In the nonpregnant female, LH controls the secretions of the corpus luteum; in the pregnant female, human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) controls them. At the end of the secretory phase, the uterine lining is ready to receive and nourish a zygote. If fertilization doesn’t occur, increasing estrogen and progesterone levels decrease LH and FSH production. Because LH is necessary to maintain the corpus luteum, a decrease in LH production causes the corpus luteum to atrophy and stop secreting estrogen and progesterone. The thickened uterine lining then begins to slough off, and menstruation begins again.

If fertilization and pregnancy do occur, the endometrium grows even thicker. After implantation of the zygote (about 5 or 6 days after fertilization), the endometrium becomes the decidua. Chorionic villi produce hCG soon after implantation, stimulating the corpus luteum to continue secreting estrogen and progesterone, which prevents further ovulation and menstruation.

HCG continues to stimulate the corpus luteum until the placenta—the vascular organ that develops to transport materials to and from the fetus—forms and starts producing its own estrogen and progesterone. After the placenta takes over hormonal production, secretions of the corpus luteum are no longer needed to maintain the pregnancy, and the corpus luteum gradually decreases its function and begins to degenerate.

PREGNANCY

Cell multiplication and differentiation begin in the zygote at the moment of conception. By about 17 days after conception, the placenta has established circulation to what is now an embryo (the term used for the conceptus between the 2nd and 7th weeks of pregnancy). By the end of the embryonic stage, fetal structures are formed. Further development now consists primarily of growth and maturation of already formed structures. From this point until birth, the conceptus is called a fetus

FIRST TRIMESTER

Normal pregnancies last an average of 280 days. Although pregnancies vary in duration, they’re conveniently divided into three trimesters.

During the first trimester, a female usually experiences physical changes, such as amenorrhea, urinary frequency, nausea and vomiting (more severe in the morning or when the stomach is empty), breast swelling and tenderness, fatigue, increased vaginal secretions, and constipation.

Within 7 to 10 days after conception, pregnancy tests, which detect hCG in the urine and serum, are usually positive. A pelvic examination at this stage can yield various findings, such as Hegar’s sign (cervical and uterine softening), Chadwick’s sign (a bluish coloration of the vagina and cervix resulting from increased venous circulation), and enlargement of the uterus. A pelvic examination will help estimate gestational age, but vaginal sonography is more accurate.

The first trimester is a critical time during pregnancy. Rapid cell differentiation makes the developing embryo or fetus highly susceptible to the teratogenic effects of viruses, alcohol, cigarettes, caffeine, and other drugs.

SECOND TRIMESTER

From the 13th to the 28th week of pregnancy, uterine and fetal size increase substantially, causing weight gain, a thickening waistline, abdominal enlargement and, possibly, reddish streaks as abdominal skin stretches (striation). In addition, pigment changes may cause skin alterations, such as linea nigra, melasma (mask of pregnancy), and a darkening of the areolae of the nipples.

Other physical changes may include diaphoresis, increased salivation, indigestion, continuing constipation, hemorrhoids, nosebleeds, and some dependent edema. The breasts become larger and heavier, and about

19 weeks after the last menstrual period, they may secrete colostrum. By about the 18th to the 20th week of pregnancy, the fetus is large enough for the mother to feel it move (quickening).

19 weeks after the last menstrual period, they may secrete colostrum. By about the 18th to the 20th week of pregnancy, the fetus is large enough for the mother to feel it move (quickening).

THIRD TRIMESTER

During this period, from the 28th week to term, the mother feels Braxton Hicks contractions—sporadic episodes of painless uterine tightening—which help strengthen uterine muscles in preparation for labor. Increasing uterine size may displace pelvic and intestinal structures, causing indigestion, protrusion of the umbilicus, shortness of breath, and insomnia. The mother may experience backaches because she walks with a swaybacked posture to counteract her frontal weight. By lying down, she can help minimize the development of varicose veins, hemorrhoids, and ankle edema.

LABOR AND DELIVERY

About 2 to 4 weeks before birth, lightening—the descent of the fetal head into the pelvis—shifts the uterine position. This relieves pressure on the diaphragm and enables the mother to breathe more easily.

Onset of labor characteristically produces low back pain and passage of a small amount of bloody “show.” A brownish or blood-tinged plug of cervical mucus may be passed up to 2 weeks before labor. As labor progresses, the cervix becomes soft, then effaces and dilates; the amniotic membranes may rupture spontaneously, causing a gush or leakage of amniotic fluid. Uterine contractions become increasingly regular, frequent, intense, and long.

Labor is usually divided into four stages:

Stage I, the longest stage, lasts from onset of regular contractions until full cervical dilation (4” [10 cm]). Average duration of this stage is about 12 hours for a primigravida and 6 hours for a multigravida.

Stage II lasts from full cervical dilation until delivery of the infant—about 1 to 3 hours for a primigravida, 30 to 60 minutes for a multigravida.

Stage III, the time between delivery and expulsion of the placenta, usually lasts several minutes (duration varies widely) but may last up to 30 minutes.

Stage IV is a period of recovery during which homeostasis is re-established. This final stage lasts 1 to 4 hours after the placenta is expelled.

SOURCES OF PATHOLOGY

In no other body part do so many interrelated physiologic functions occur so close together as in the area of the female reproductive tract. Besides the internal genitalia, the female pelvis contains the organs of the urinary and the GI systems (bladder, ureters, urethra, sigmoid colon, and rectum). The reproductive tract and its surrounding area are thus the site of urination, defecation, menstruation, ovulation, copulation, impregnation, and parturition. It’s easy to understand how an abnormality in one pelvic organ can readily induce abnormality in another.

When conducting a pelvic examination, therefore, you must consider all possible sources of pathology. Remember that some serious abnormalities of the pelvic organs can be asymptomatic. Remember, too, that some abnormal findings in the pelvic area may result from pathologic changes in other organ systems, such as the upper urinary and GI tracts, the endocrine glands, and the neuromusculoskeletal system. Pain symptoms are often associated with the menstrual cycle; therefore, in many common diseases of the female reproductive tract, such pain follows a cyclic pattern. A patient with pelvic inflammatory disease, for example, may complain of increasing premenstrual pain that’s relieved by onset of menstruation.

PELVIC EXAMINATION

A pelvic examination and a thorough patient history are essential for any patient with symptoms related to the reproductive tract or adjacent body systems. Document any history of pregnancy, miscarriage, and abortion. Ask the patient if she has experienced any recent changes in her urinary habits or menstrual cycle. If she practices birth control, find out what method she uses and whether she has experienced any adverse effects.

Then prepare the patient for the pelvic examination as follows:

Ask the patient if she has douched within the past 24 hours. Explain that douching washes away cells or organisms that the examination is designed to evaluate.

Check weight and blood pressure.

For the patient’s comfort, instruct her to empty her bladder before the examination. Provide a urine specimen container if needed.

To help the patient relax, which is essential for a thorough pelvic examination, explain what the examination entails and why it’s necessary.

If the patient is scheduled for a Papanicolaou (Pap) test, inform her that another smear may have to be taken later if there are abnormal findings with the first test. Reassure her that this is done to confirm the first test’s results. If she has never had a Pap test before, tell her it may be uncomfortable.

After the Pap test, a bimanual examination is performed to assess the size and location of the ovaries and uterus.

After the examination, offer the patient premoistened tissues to clean the vulva.

OTHER DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

Diagnostic measures for gynecologic disorders also include the following tests, which can be performed in the physician’s office:

wet smear to examine vaginal secretions for specific organisms, such as Trichomonas vaginalis, bacterial vaginosis, and Candida albicans, or to evaluate semen specimens collected in connection with rape or infertility cases

endometrial biopsy to assess hormonal secretions of the corpus luteum, to determine whether normal ovulation is occurring, and to check for neoplasia

dilatation and curettage with hysteroscopy to evaluate atypical bleeding and to detect carcinoma

Laparoscopy, used to evaluate infertility, dysmenorrhea, and pelvic pain, and as a means of sterilization, is usually performed in a health care facility while the patient is under anesthesia. Increasingly, however, it’s being performed as a less invasive procedure under conscious sedation in an office setting using microlaparoscopic technique.

GYNECOLOGIC DISORDERS

Premenstrual syndrome

Also designated late luteal phase dysphoric disorder (LLPD) in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision, premenstrual syndrome (PMS) is characterized by varying symptoms that appear 7 to 14 days before menses and usually subside with its onset. The effects of PMS range from minimal discomfort to severe, disruptive symptoms and can include nervousness, irritability, depression, and multiple somatic complaints.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

The list of biological theories offered to explain the cause of PMS is impressive. It includes such conditions as a progesterone deficiency in the menstrual cycle’s luteal phase and vitamin deficiencies. Although there’s no evidence that PMS is hormonally mediated, failure to identify a specific disorder with a specific mechanism suggests that PMS represents a variety of manifestations triggered by normal physiologic hormonal changes. Researchers believe that 70% to 90% of women experience PMS at some time during their childbearing years, usually between ages 25 and 45.

COMPLICATIONS

Depression

Inability to function at home, work, or school

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Clinical effects vary widely among patients and may include any combination of the following:

behavioral—mild to severe personality changes, nervousness, hostility, irritability, agitation, sleep disturbances, fatigue, lethargy, and depression

somatic—breast tenderness or swelling, abdominal tenderness or bloating, joint pain, headache, edema, diarrhea or constipation, and exacerbations of skin problems (such as acne or rashes), respiratory problems (such as asthma), or neurologic problems (such as seizures)

PMS may need to be differentiated from premenstrual dysphoric disorder, which is a more severe form of PMS that’s marked by severe depression, irritability, and tension before menstruation. (See Premenstrual dysphoric disorder, page 1030.)

DIAGNOSIS

The patient history shows typical symptoms related to the menstrual cycle. To help ensure an accurate history, the patient may be asked to record menstrual symptoms and body temperature on a calendar for 2 to 3 months prior to diagnosis. Estrogen and progesterone blood levels may be evaluated to help rule out hormonal imbalance. A psychological evaluation is also recommended to rule out or detect an underlying psychiatric disorder.

TREATMENT

Educating and reassuring patients that PMS is a real physiologic syndrome are important parts of treatment. Because treatment is predominantly symptomatic, each patient must learn to cope with her own individual set of symptoms.

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is a severe form of premenstrual syndrome (PMS) that has a cyclical occurrence of psychiatric symptoms that starts after ovulation (usually the week before the onset of menstruation) and ends within the first day or two of menses. Its underlying cause and pathophysiology remain unclear. However, researchers theorize that normal cyclic changes in the body cause abnormal responses to neurotransmitters, such as serotonin, resulting in physical and behavioral signs and symptoms.

PMDD affects as many as 1 in 20 American women who have regular menstrual periods. It’s unclear why some women are affected while others aren’t.

How PMDD and PMS differ

PMDD is characterized by severe monthly mood swings and physical signs and symptoms that interfere with everyday life. Compared to PMS, its signs and symptoms are abnormal and unmanageable. Although depression, anxiety, and sadness are common with PMS, in PMDD, these symptoms are extreme. Some women may feel the urge to hurt or kill themselves or others.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision, sets these criteria for diagnosing PMDD:

functional impairment

predominant mood symptoms, with one being affective

symptoms beginning 1 week before the onset of menstruation

symptoms that aren’t due to any underlying primary mood disorder.

In addition, at least five of the following symptoms must be present:

appetite changes

decreased interests

difficulty concentrating

fatigue

feelings of being overwhelmed

insomnia or hypersomnia

irritability

“low mood”

mood swings

physical symptoms

tension

Treatment may include calcium and magnesium supplementation, vitamins (such as B complex), prostaglandin inhibitors, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Diuretics may be prescribed for patients who experience significant weight gain due to fluid retention. Psychiatric medications and therapy may be prescribed for women who develop anxiety, irritability, or depression. Hormonal therapy may include a trial on hormonal contraceptives, which may either decrease or increase PMS symptoms. The use of progesterone vaginal suppositories during the second half of the menstrual cycle is still controversial.

For treatment to be effective, the patient may have to maintain a diet that’s low in simple sugars, caffeine, and salt.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Inform the patient that self-help groups exist for women with PMS; help her contact such a group if appropriate.

Obtain a complete patient history to help identify any emotional problems that may contribute to PMS. Refer the patient for psychological counseling if necessary.

Suggest that the patient seek further medical consultation if symptoms are severe and inter fere with her normal lifestyle.

♦ If possible, discuss with your patient ways she can modify her lifestyle, such as making changes in her diet and avoiding stimulants and alcohol

♦Encourage your patient to get regular exercise and adequate rest.

Dysmenorrhea

Dysmenorrhea—painful menstruation—is the most common gynecologic complaint and a leading cause of absenteeism from school (affecting 10% of high school girls each month) and work (causing about 140 million lost work hours annually). Dysmenorrhea can occur as a primary disorder or secondary to an underlying disease. Because primary dysmenorrhea is self-limiting, the prognosis is generally good. The prognosis for secondary dysmenorrhea depends on the underlying disorder.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

Although primary dysmenorrhea has no known single cause, possible contributing factors include hormonal imbalances and psychogenic factors. The pain of dysmenorrhea probably results from increased prostaglandin secretion, which intensifies normal uterine contractions. (See Causes of pelvic pain.) Dysmenorrhea may also be secondary to such gynecologic disorders as endometriosis, cervical stenosis, uterine leiomyomas, uterine malposition, pelvic inflammatory disease, pelvic tumors, or adenomyosis.

Because dysmenorrhea almost always follows an ovulatory cycle, both the primary and secondary forms are rare during the anovulatory cycles of menses. After age 20, dysmenorrhea is generally secondary.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Dysmenorrhea produces sharp, intermittent, cramping lower abdominal pain, which usually radiates to the back, thighs, groin, and vulva. Such pain—sometimes compared to labor pains—typically starts with or immediately before menstrual flow and peaks within 24 hours. Dysmenorrhea may also be associated with the characteristic signs and symptoms of premenstrual syndrome (urinary frequency, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, chills, abdominal bloating, painful breasts, depression, and irritability).

DIAGNOSIS

Pelvic examination and a detailed patient history may help suggest the cause of dysmenorrhea.

Primary dysmenorrhea is diagnosed when secondary causes are ruled out. Appropriate tests (such as laparoscopy, dilatation and curettage, and pelvic ultrasound) are used to diagnose underlying disorders in secondary dysmenorrhea.

TREATMENT

Initial treatment aims to relieve pain. Pain-relief measures may include:

analgesics (such as aspirin) for mild to moderate pain (most effective when taken 24 to 48 hours before onset of menses; are especially effective for treating dysmenorrhea because they also inhibit prostaglandin synthesis; stronger anti-inflammatories may be used).

opioids if pain is severe (infrequently used).

prostaglandin inhibitors (such as naproxen and ibuprofen) to relieve pain by decreasing the severity of uterine contractions.

heat applied locally to the lower abdomen (may relieve discomfort in mature women but isn’t recommended in young adolescents because appendicitis may mimic dysmenorrhea).

Causes of pelvic pain

The characteristic pelvic pain of dysmenorrhea must be distinguished from the acute pain caused by many other disorders, such as:

GI disorders: appendicitis, acute diverticulitis, acute or chronic cholecystitis, chronic cholelithiasis, acute pancreatitis, peptic ulcer perforation, intestinal obstruction

pregnancy disorders: impending abortion (pain and bleeding early in pregnancy), ectopic pregnancy, abruptio placentae, uterine rupture, leiomyoma degeneration, toxemia

reproductive disorders: acute salpingitis, chronic inflammation, degenerating fibroid, ovarian cyst torsion

urinary tract disorders: cystitis, renal calculi

Other conditions that may mimic dysmenorrhea include ovulation and normal uterine contractions experienced in pregnancy. Emotional conflicts can cause psychogenic (functional) pain.

For primary dysmenorrhea, administration of sex steroids is an effective alternative to treatment with antiprostaglandins or analgesics. Such therapy usually consists of hormonal contraceptives to relieve pain by suppressing ovulation. However, patients who are attempting pregnancy should rely on antiprostaglandin therapy instead of hormonal contraceptives to relieve symptoms of primary dysmenorrhea.

Because persistently severe dysmenorrhea may have a psychogenic cause, psychological evaluation and appropriate counseling may be helpful.

In secondary dysmenorrhea, treatment is designed to identify and correct the underlying cause. This may include surgical treatment of underlying disorders, such as endometriosis or uterine leiomyomas. However, surgical treatment is recommended only after conservative therapy fails.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Effective management of the patient with dysmenorrhea focuses on relief of symptoms, emotional support, and appropriate patient teaching, especially for the adolescent.

Obtain a complete history, focusing on the patient’s gynecologic complaints, including detailed information on any signs and symptoms of pelvic disease, such as excessive bleeding, changes in bleeding pattern, vaginal discharge, and dyspareunia.

Provide thorough patient teaching. Explain normal female anatomy and physiology to the patient, as well as the nature of dysmenorrhea. This may be a good opportunity, depending on circumstances, to provide the adolescent patient with information on pregnancy and contraception.

Encourage the patient to keep a detailed record of her menstrual symptoms and to seek medical care if her symptoms persist.

Instruct the patient on some home care remedies that may be helpful in relieving discomfort, such as applying a heating pad to the lower abdomen, taking warm showers or baths, drinking warm beverages, and performing circular massage with the fingertips around the lower abdomen.

Encourage the patient to walk or exercise regularly. Recommend pelvic rocking exercises and relaxation techniques, such as meditation or yoga. Let her know that keeping her legs elevated while lying down or lying on her side with her knees bent may also increase comfort.

Instruct the patient to eat light but frequent meals and to follow a diet rich in foods high in complex carbohydrates, such as whole grains, fruits, and vegetables. Tell her to avoid alcohol and foods high in salt, sugar, and caffeine.

Vulvovaginitis

Vulvovaginitis is inflammation of the vulva (vulvitis) and vagina (vaginitis). Because of the proximity of these two structures, inflammation of one occasionally causes inflammation of the other. Vulvovaginitis may occur at any age and affects most females at some time. The prognosis is excellent with treatment.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

Common causes include:

infection with Trichomonas vaginalis, a protozoan flagellate usually transmitted through sexual intercourse.

infection with Candida albicans, a fungus that requires glucose for growth. Incidence rises during the menstrual cycle’s secretory phase. (Such infection occurs twice as often in pregnant females as in nonpregnant females. It also commonly affects users of hormonal contracep tives, patients who are diabetic, and patients receiving systemic therapy with broad-spectrum antibiotics [incidence may reach 75%])

excess of nonspecific vaginal bacteria with little or absent inflammation, commonly referred to as Gardnerella vaginalis or nonspecific vaginitis.

parasitic infection (Phthirus pubis [crab louse]).

trauma (skin breakdown may lead to secondary infection).

poor personal hygiene.

chemical irritations, or allergic reactions to hygiene sprays, douches, detergents, clothing, or toilet paper.

vulval atrophy in menopausal women due to decreasing estrogen levels.

retention of a foreign body, such as a tampon or diaphragm.

COMPLICATIONS

Infection

Perineal inflammation and edema

Skin breakdown

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

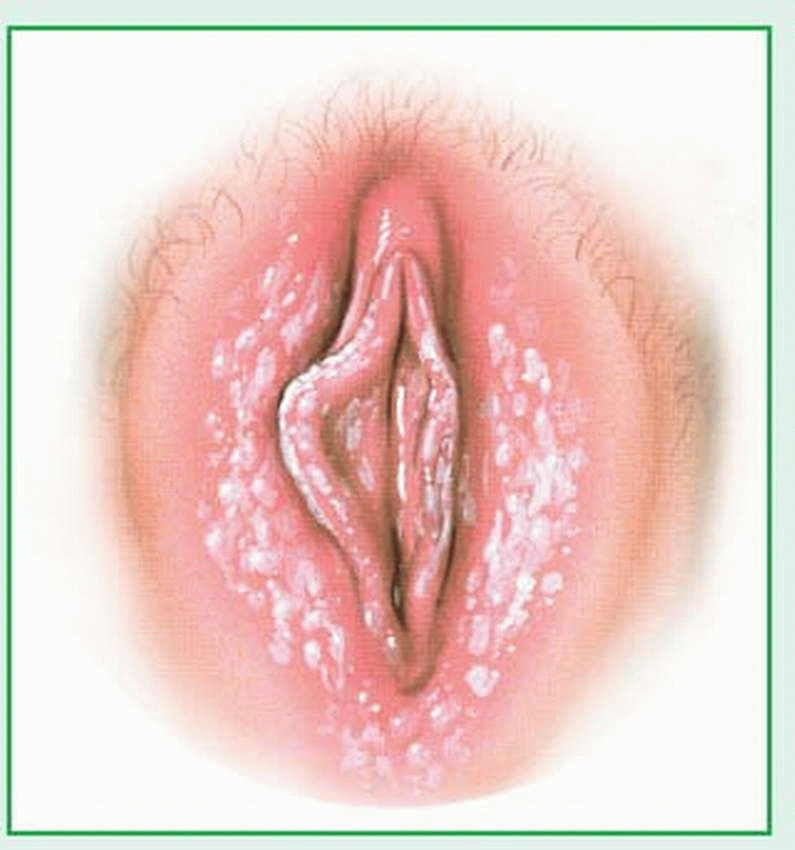

In trichomonal vaginitis, vaginal discharge is thin, bubbly, green-tinged, and malodorous. This infection causes marked irritation and itching, and urinary symptoms, such as burning and frequency. Candidal vaginitis produces a thick, white, cottage cheese-like discharge and red, edematous mucous membranes, with white flecks adhering to the vaginal wall, and is often accompanied by intense itching. (See Candida infection.) G. vaginalis produces a gray, foul, “fishy” smelling discharge.

Acute vulvitis causes a mild to severe inflammatory reaction, including edema, erythema, burning, and pruritus. Severe pain on urination and dyspareunia may necessitate immediate treatment. Herpes infection may cause painful ulceration or vesicle formation during the active phase.

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis of vulvovaginitis requires identification of the infectious organism during microscopic examination of vaginal discharge on a wet slide preparation (a drop of vaginal discharge placed in normal saline solution). In some cases, a culture of the vaginal discharge may identify the organism causing the infection.

TREATMENT

The cause of vulvovaginitis determines the appropriate treatment. It may include oral or topical antibiotics, antifungal creams, antibacterial creams, or similar medications. An antihistamine may be prescribed for allergic reactions. Cold compresses or cool sitz baths may provide relief from pruritus in acute vulvitis; severe inflammation may require warm compresses. Other therapy includes avoiding drying soaps, wearing loose clothing to promote air circulation, and applying topical corticosteroids to reduce inflammation. Chronic vulvitis may respond to topical hydrocortisone or antipruritics and good hygiene (especially in elderly or incontinent patients). Topical estrogen ointments may be used to treat atrophic vulvovaginitis. No cure exists for herpesvirus infections; however, oral and topical acyclovir decreases the duration and symptoms of active lesions.

If in STD is diagnosed, it’s very important that partners also receive treatment, even if there are no symptoms. Failure of partners to receive treatment can lead to continual reinfection, which may eventually lead to infertility and affect the patient’s overall health.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Ask the patient if she has any drug allergies. Stress the importance of taking the medication for the length of time prescribed, even if symptoms subside.

Teach the patient how to insert vaginal ointments and suppositories. Tell her to remain prone for at least 30 minutes after insertion to promote absorption (insertion at bedtime is ideal). Suggest she wear a pad to prevent staining her underclothing.

Report notifiable cases of STD to local public health authorities.

Tell the patient that persistent, recurring candidiasis may suggest diabetes, undiagnosed pregnancy, or immunologic issues.

Encourage good hygiene.

Advise the patient with a history of recurrent vulvovaginitis to wear all-cotton underpants. Advise her to avoid wearing tight-fitting pants and panty hose, which encourage the growth of the infecting organisms. Removing underpants at night is also helpful

Encourage the use of condoms to avoid contracting an STD

Advise the patient to avoid the use of irritants such as scented soaps and feminine hygiene products.

Advise the patient to avoid baths, douching, and the use of hot tubs

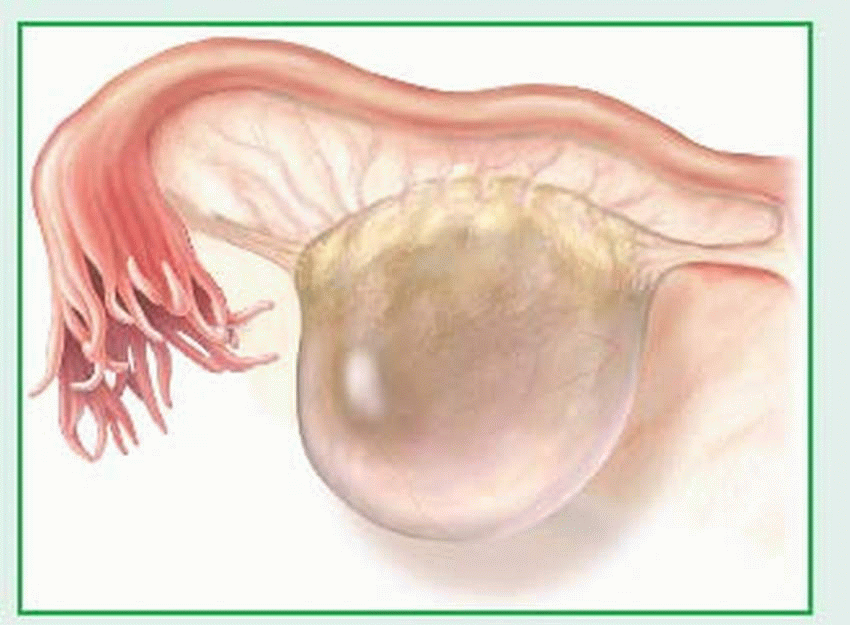

Ovarian cysts

Ovarian cysts are usually nonneoplastic sacs on an ovary that contain fluid or semisolid material. Although these cysts are usually small and produce no symptoms, they generally require thorough investigation as possible sites of malignant change. Common ovarian cysts include follicular cysts, lutein cysts (granulosa-lutein [corpus luteum] and thecalutein cysts), and polycystic ovarian disease. Ovarian cysts can develop at any time between puberty and menopause, including during pregnancy. Granulosa-lutein cysts occur infrequently, usually during early pregnancy. The prognosis for nonneoplastic ovarian cysts is excellent.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

Follicular cysts are generally very small and arise from follicles that overdistend. When such cysts persist into menopause, they secrete excessive amounts of estrogen in response to the hypersecretion of follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone that normally occurs during menopause. (See Follicular cyst, page 1034.)

Granulosa-lutein cysts, which occur within the corpus luteum, are functional, nonneoplastic enlargements of the ovaries caused by excessive accumulation of blood during the hemorrhagic phase of the menstrual cycle. The-ca-lutein cysts are commonly bilateral and filled with clear, straw-colored fluid; they’re often associated with hydatidiform mole, choriocarcinoma, or hormone therapy (with human chorionic gonadotropin [hCG] or clomiphene citrate).

COMPLICATIONS

Amenorrhea

Infertility

Oligomenorrhea

Secondary dysmenorrhea

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Small ovarian cysts (such as follicular cysts) usually don’t produce symptoms unless torsion or rupture causes signs of an acute abdomen (vomiting, abdominal tenderness, distention, and rigidity). Large or multiple cysts may induce mild pelvic discomfort, low back pain, dyspareunia, or abnormal uterine bleeding secondary to a disturbed ovulatory pattern. Ovarian cysts with torsion induce acute abdominal pain similar to that of appendicitis.

Granulosa-lutein cysts that appear early in pregnancy may grow as large as 2” to 21/2” (5 to 6 cm) in diameter and produce unilateral pelvic discomfort and, if rupture occurs, massive intraperitoneal hemorrhage. In nonpregnant women, these cysts may cause delayed menses, followed by prolonged or irregular bleeding. Polycystic ovary syndrome may also produce secondary amenorrhea, oligomenorrhea, or infertility.

DIAGNOSIS

Generally, characteristic clinical features suggest ovarian cysts.

Visualization of the ovary through ultrasound, computed tomography scan, magnetic resonance imaging, laparoscopy, or surgery (often for another condition) confirms ovarian cysts.

Extremely elevated hCG titers strongly suggest theca-lutein cysts. Pregnancy, including molar pregnancy, must be ruled out.

TREATMENT

Follicular cysts generally don’t require treatment because they tend to disappear spontaneously within 60 to 90 days. However, if they interfere with daily activities, clomiphene citrate by mouth for 5 days or progesterone I.M. (also for 5 days) re-establishes the ovarian hormonal cycle and induces ovulation. Hormonal contraceptives haven’t been proven to accelerate involution of functional cysts (including both types of lutein cysts and follicular cysts).

Treatment for granulosa-lutein cysts that occur during pregnancy is aimed at relieving symptoms because these cysts diminish during the third trimester and rarely require surgery. Theca-lutein cysts disappear spontaneously after elimination of the hydatidiform mole, destruction of choriocarcinoma, or discontinuation of hCG or clomiphene citrate therapy.

Surgery, in the form of laparoscopy or exploratory laparotomy with possible ovarian cystectomy or oophorectomy, may become necessary if an ovarian cyst is found to be persistent or suspicious.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Thorough patient teaching is a primary consideration. Carefully explain the cyst’s nature, the type of discomfort the patient may experience, and how long the condition is expected to last.

Preoperatively, watch for signs of cyst rupture, such as increasing abdominal pain, distention, and rigidity. Monitor vital signs for fever, tachypnea, or hypotension, which may indicate peritonitis or intraperitoneal hemorrhage. Administer sedatives, as ordered, to ensure adequate rest before surgery.

Postoperatively, encourage frequent movement in bed and early ambulation, as ordered. Early ambulation prevents pulmonary embolism.

Provide emotional support. Offer appropriate reassurance if the patient fears cancer or infertility.

Before discharge, advise the patient to in crease her activities at home gradually—prefer ably over 4 to 6 weeks. Tell her to abstain from sexual intercourse and not to use tampons and douches during this period.

Polycystic ovary syndrome

Polycystitic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a metabolic syndrome characterized by multiple ovarian cysts. It produces a syndrome of hormonal disturbances that includes insulin resistance, obesity, hirsutism, acne, and ovulation and fertility problems. With proper treatment, the prognosis for ovulation and fertility is good.

As with all anovulation syndromes, the pulsatile release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone is lacking. This allows for the initial ovarian follicle development to be normal, but many small follicles begin to accumulate because there’s no selection of a dominant follicle. These follicles then respond abnormally to hormonal stimulation, causing an abnormal estrogen secretion during the menstrual cycle.

Insulin, along with other hormones, plays a role in regulating ovary function. Insulin resistance results in high levels of circulating insulin. The high levels of insulin affect the function of cells, including ovary cells. This can lead to anovulation and infertility.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

The precise cause of PCOS isn’t known. There are several theories regarding the cause, including abnormal enzyme activity triggering excess androgen secretion from the ovaries and adrenal glands, as well as endocrine abnormalities or genetic links.

It’s most common in women under age 30. In the United States it affects 4% to 12% of women of childbearing age.

COMPLICATIONS

Hypertension

Increased risk of breast or endometrial cancer

Infertility

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Signs and symptoms of PCOS include mild pelvic discomfort, lower back pain, and dyspareunia caused by multiple ovarian cysts, abnormal uterine bleeding secondary to disturbed ovulatory pattern, hirsutism and malepattern hair loss that result from abnormal patterns of estrogen secretion, obesity caused by abnormal hormone regulation, and acne caused by excess sebum production that results from disturbed androgen secretion.

DIAGNOSIS

In PCOS, bilaterally enlarged polycystic ovaries can be seen on ultrasound examination. Tests reveal slight elevation of urinary 17-ketosteroids and anovulation (shown by basal body temperature graphs and endometrial biopsy). Blood testing reveals an elevated luteinizing hormone to follicle-stimulating hormone ratio (usually 3:1 or greater), and elevated testosterone, androstenedione, and glucose levels. Direct observation must rule out paraovarian cysts of the broad ligaments, salpingitis, endometriosis, and neoplastic cysts. Ultrasonography, abdominal magnetic imaging, or surgery (commonly done for another condition) allows visualization of the ovary, which may confirm the presence of ovarian cysts.

TREATMENT

Treatment of PCOS may include use of such drugs as clomiphene citrate to induce ovulation or medroxyprogesterone acetate for 10 days of every month for the patient who doesn’t want to become pregnant. For the patient who needs reliable contraception, a low-dose hormonal contraceptive is used to treat abnormal bleeding. Surgical treatment may involve a hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy for refractory pain and bleeding.

Drugs such as metformin, pioglitazone, or rosiglitazone can be used to make cells more insulin-sensitive.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Provide appropriate postoperative care, including the following:

Watch for signs of cyst rupture, such as increasing abdominal pain, distention, and rigidity.

Monitor the patient’s vital signs for fever, tachypnea, or hypotension (possibly indicating peritonitis or intraperitoneal hemorrhage).

Encourage frequent movement in bed and early ambulation, as ordered, to prevent pulmonary embolism.

Provide emotional support, offering appropriate reassurance if the patient fears cancer or infertility.

Before discharge, if the patient is overweight, discuss the importance of weight reduction and the role it may play in reducing insulin resis tance.

Endometriosis

Endometriosis is the presence of endometrial tissue outside the lining of the uterine cavity. Such ectopic tissue is generally confined to the pelvic area, most commonly around the ovaries, uterovesical peritoneum, uterosacral ligaments, and cul-de-sac, but it can appear anywhere in the body. This ectopic endometrial tissue responds to normal stimulation in the same way that the endometrium does. During menstruation, the ectopic tissue bleeds, which causes inflammation of the surrounding tissues. This inflammation causes fibrosis, leading to adhesions that produce pain and infertility.

Active endometriosis usually occurs between ages 20 and 40; it’s uncommon before age 20. Severe symptoms of endometriosis may have an abrupt onset or may develop over many years. This disorder usually becomes progressively severe during the menstrual years; after menopause, it may subside.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

The mechanisms by which endometriosis causes symptoms, including infertility, are unknown. The main theories to explain this disorder are:

transtubal regurgitation of endometrial cells and implantation at ectopic sites

coelomic metaplasia (repeated inflammation may induce metaplasia of mesothelial cells to the endometrial epithelium)

lymphatic or hematogenous spread to explain extraperitoneal disease

Endometriosis occurs in 10% of women during the reproductive years. Prevalence may be as high as 25% to 35% among infertile women. A woman with a mother or sister with endometriosis is six times more likely to develop endometriosis than a woman without this familial history.

COMPLICATIONS

Anemia

Infertility

Spontaneous abortion

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

The classic symptom of endometriosis is acquired dysmenorrhea, which may produce constant pain in the lower abdomen and in the vagina, posterior pelvis, and back. This pain usually begins from 5 to 7 days before menses reaches its peak and lasts for 2 to 3 days. It differs from primary dysmenorrheal pain, which is more cramplike and concentrated in the abdominal midline. However, the pain’s severity doesn’t necessarily indicate the extent of the disease.

Other clinical features depend on the location of the ectopic tissue:

ovaries and oviducts: infertility and profuse menses

ovaries or cul-de-sac: deep-thrust dyspareunia

bladder: suprapubic pain, dysuria, hematuria

small bowel and appendix: nausea and vomiting, which worsen before menses, and abdominal cramps

cervix, vagina, and perineum: bleeding from endometrial deposits in these areas during menses

The primary complications of endometriosis are infertility and chronic pelvic pain.

DIAGNOSIS

Pelvic examination may suggest endometriosis. Palpation may detect multiple tender nodules on uterosacral ligaments or in the rectovaginal septum in one-third of patients. These nodules enlarge and become more tender during menses. Palpation may also uncover ovarian enlargement in the presence of endometrial cysts on the ovaries or thickened, nodular adnexa (as in pelvic inflammatory disease). Laparoscopy must confirm the diagnosis and determine the disease’s stage before treatment is started. Endometriosis is classified in stages: Stage I, mild; Stage II, moderate; Stage III, severe; and Stage IV, extensive.

TREATMENT

Treatment varies according to the disease’s stage and the patient’s age and desire to have children. Conservative therapy for young women who want to have children includes androgens, such as danazol, which produce a temporary remission in Stages I and II. Progestins and hormonal contraceptives also relieve symptoms. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, by inducing a pseudomenopause and, thus, a “medical oophorectomy,” may cause a remission of disease and are commonly used. However, medical therapy remains inadequate.

When ovarian masses are present, surgery must rule out cancer. Conservative surgery includes laparoscopic removal of endometrial

implants with conventional or laser techniques and presacral neurectomy for severe dysmenorrhea. The treatment of choice for women who don’t want to bear children or for extensive disease is a total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

implants with conventional or laser techniques and presacral neurectomy for severe dysmenorrhea. The treatment of choice for women who don’t want to bear children or for extensive disease is a total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Because infertility is a possible complication, advise the patient who wants children not to postpone childbearing.

Recommend an annual pelvic examination and Papanicolaou test to all patients.

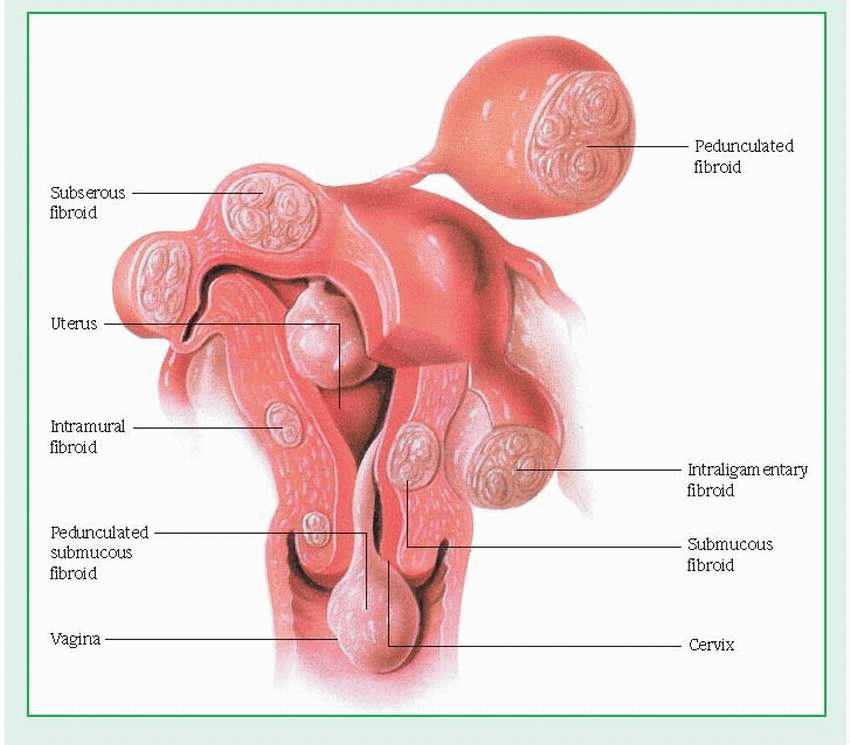

Uterine leiomyomas

The most common benign tumors in women, uterine leiomyomas, also known as myomas, fibromyomas, or fibroids, are smooth-muscle tumors. They usually occur in multiples in the uterine corpus, although they may appear on the cervix or on the round or broad ligament. Though uterine leiomyomas are often called fibroids, this term is misleading because they consist of muscle cells and not fibrous tissue.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

The cause of uterine leiomyomas is unknown, but steroid hormones, including estrogen and progesterone, and several growth factors, including epidermal growth factor, have been implicated as regulators of leiomyoma growth. Leiomyomas typically arise after menarche and regress after menopause, implicating estrogen as a promoter of leiomyoma growth.

Uterine leiomyomas occur in 20% to 25% of women of reproductive age and reportedly affect three times as many Black women as White women. The tumors become malignant (leiomyosarcoma) in only 0.1% or less of patients.

COMPLICATIONS

Anemia

Dystocia

Infertility

Intestinal obstruction

Preterm labor

Spontaneous abortion

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Leiomyomas may be located within the uterine wall or may protrude into the endometrial cavity or from the serosal surface of the uterus. (See Uterine fibroids, page 1038.) Most leiomyomas produce no symptoms. The most common symptom is abnormal bleeding, which typically presents clinically as menorrhagia. Uterine leiomyomas probably don’t cause pain directly except when associated with torsion of a pedunculated subserous tumor. Pelvic pressure and impingement on adjacent viscera are common indications for treatment. Other symptoms may include urine retention, constipation, or dyspareunia.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical findings and patient history may suggest uterine leiomyomas. Bimanual examination may reveal an enlarged, firm, nontender, and irregularly contoured uterus. Ultrasound (transvaginal or pelvic) or magnetic resonance imaging allows accurate assessment of the dimensions, number, and location of tumors. Other diagnostic procedures include hysterosalpingography, dilatation and curettage, endometrial biopsy, and laparoscopy.

TREATMENT

Treatment depends on the symptoms’ severity, the tumors’ size and location, and the patient’s age, parity, pregnancy status, desire to have children, and general health.

Treatment options include nonsurgical as well as surgical procedures. Nonsurgical methods include taking serial histories and performing physical assessments at clinically indicated intervals and administering gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues, which are capable of rapidly suppressing pituitary gonadotropin release, leading to profound hypoestrogenemia and a 50% reduction in uterine volume. The peak effects of these GnRH analogues occur in the 12th week of therapy. The benefits are reduction in tumor size before surgery, reduction in intraoperative blood loss, and an increase in preoperative hematocrit. GnRH analogues aren’t curative.

Surgical procedures include abdominal, laparoscopic, or hysteroscopic myomectomy— for patients who want to preserve fertility. Myolysis and uterine artery embolization can successfully treat fibroids without hysterectomy or major surgery. Performed on an outpatient basis, this laparoscopic procedure coagulates the fibroids and preserves the uterus and the patient’s childbearing potential. Hysterectomy is the definitive treatment for symptomatic women who have completed childbearing, but uterine artery embolization may be an alternative in some situations.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Tell the patient to report any abnormal bleeding or pelvic pain immediately.

If a hysterectomy or oophorectomy is indicated, explain the operation’s effects on menstruation, menopause, and sexual activity to the patient.

Reassure the patient that she most likely won’t experience premature menopause if her ovaries are left intact.

If it’s necessary for the patient to have a multiple myomectomy, make sure she understands pregnancy is still possible. Explain that a cesarean delivery may be indicated.

Precocious puberty

In females, precocious puberty is the early onset of pubertal changes: breast development, pubic and axillary hair development, and menarche before age 9. (Normally, the mean age for menarche is 13.) In true precocious puberty, the ovaries mature and pubertal changes progress in an orderly manner. In pseudoprecocious puberty, pubertal changes occur without corresponding ovarian maturation.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

About 85% of all cases of true precocious puberty in females are constitutional, resulting from early development and activation of the endocrine glands without corresponding abnormality. Other causes of true precocious puberty are pathologic and include central nervous system (CNS) disorders resulting from tumors, trauma, infection, or other lesions. These CNS disorders include hypothalamic tumors, intracranial tumors (pinealoma, granuloma, hamartoma), hydrocephaly, degenerative encephalopathy, tuberous sclerosis, neurofibromatosis, encephalitis, skull injuries, meningitis, and peptic arachnoiditis. McCune-Albright syndrome,

Silver’s syndrome, and juvenile hypothyroidism are conditions often associated with female precocity.

Silver’s syndrome, and juvenile hypothyroidism are conditions often associated with female precocity.

Pseudoprecocious puberty may result from increased levels of sex hormones due to ovarian and adrenocortical tumors, adrenocortical virilizing hyperplasia, or ingestion of estrogens or androgens. It may also result from increased end-organ sensitivity to low levels of circulating sex hormones, whereby estrogens promote premature breast development and androgens promote premature pubic and axillary hair growth.

Risk factors include race (more Blacks are affected than Whites), sex (more girls are affected than boys), and obesity.

Other signs may include underarm hair growth, acne, and adult-type body odor.

COMPLICATIONS

Polycystic ovary syndrome

Short stature

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

The usual pattern of precocious puberty in females is a rapid growth spurt, thelarche (breast development), pubarche (pubic hair development), and menarche—all before age 9. These changes may occur independently or simultaneously.

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis requires a complete patient history, a thorough physical examination, and special tests to differentiate between true and pseudoprecocious puberty and to indicate what treatment may be necessary. X-rays of the hands, wrists, knees, and hips determine bone age and possible premature epiphyseal closure. Other tests detect abnormally high hormonal levels for the patient’s age: vaginal smear for estrogen secretion, urinary tests for gonadotropic activity and excretion of 17-ketosteroids, and radioimmunoassay for both luteinizing and folliclestimulating hormones.

As indicated, ultrasound, laparoscopy, or exploratory laparotomy may verify a suspected abdominal lesion; EEG, ventriculography, pneumoencephalography, computed tomography scan, or angiography can detect CNS disorders.

TREATMENT

Treatment of constitutional true precocious puberty may include medroxyprogesterone to reduce secretion of gonadotropins and prevent menstruation. Other therapy depends on the cause of precocious puberty and its stage of development:

Adrenogenital syndrome necessitates cortical or adrenocortical steroid replacement.

Abdominal tumors necessitate surgery to remove ovarian and adrenal tumors. Regression of secondary sex characteristics may follow such surgery, especially in young children.

Choriocarcinomas require surgery and chemotherapy.

Hypothyroidism requires thyroid extract or levothyroxine to decrease gonadotropic secretions.

Drug ingestion requires that the medication be discontinued.

In precocious thelarche and pubarche, no treatment is necessary.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

The dramatic physical changes produced by precocious puberty can be upsetting and alarming for the child and her family. Provide a calm, supportive atmosphere, and encourage the patient and her family to express their feelings about these changes. Explain all diagnostic procedures and tell the patient and her family that surgery may be necessary.

Explain the condition to the child in terms she can understand to prevent feelings of shame and loss of self-esteem. Provide appropriate sex education, including information on menstruation and related hygiene.

Tell parents that, although their daughter seems physically mature, she isn’t psychologically mature, and the discrepancy between physical appearance and psychological and psychosexual maturation may create problems. Warn them against expecting more of her than they would expect of other children her age.

Suggest that parents continue to dress their daughter in clothes that are appropriate for her age and that don’t call attention to her physical development.

Reassure parents that precocious puberty doesn’t usually precipitate precocious sexual behavior.

Menopause

Menopause is the cessation of menstruation. It results from a complex syndrome of physiologic changes—the climacteric—caused by declining ovarian function. The climacteric produces various body changes, the most dramatic being menopause.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

Physiologic menopause, the normal decline in ovarian function due to aging, begins in most

women between ages 45 and 55, on average 51, and results in infrequent ovulation, decreased menstrual function and, eventually, cessation of menstruation.

Pathologic (premature) menopause, the gradual or abrupt cessation of menstruation before age 40, occurs idiopathically in about 1% of women in the United States. However, cer tain diseases, especially severe infections and reproductive tract tumors, may cause patho logic menopause by seriously impairing ovar ian function. Other factors that may precipitate pathologic menopause include malnutrition, chemotherapy, debilitation, extreme emotional stress, excessive radiation exposure, and surgi cal procedures that impair ovarian blood supply.

COMPLICATIONS

Atherosclerosis

Osteoporosis

Urinary incontinence

Weight gain

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Many menopausal women are asymptomatic but some have severe symptoms. The decline in ovarian function and consequent decreased estrogen level produce menstrual irregularities: a decrease in the amount and duration of menstrual flow, spotting, and episodes of amenorrhea and polymenorrhea (possibly with hypermenorrhea). Irregularities may last a few months or persist for several years before menstruation ceases permanently.

The following body system changes may occur (usually after the permanent cessation of menstruation):

▪ Reproductive system—Menopause may cause shrinkage of vulval structures and loss of subcutaneous fat, possibly leading to atrophic vulvitis; atrophy of vaginal mucosa and flatten ing of vaginal rugae, possibly causing bleeding after coitus or douching; vaginal itching and discharge from bacterial invasion; and loss of capillaries in the atrophying vaginal wall, caus ing the pink, rugal lining to become smooth and white. Menopause may also produce excessive vaginal dryness and dyspareunia due to de creased lubrication from the vaginal walls and decreased secretion from Bartholin’s glands; smaller ovaries and oviducts; and progressive pelvic relaxation as the supporting structures lose their tone due to the absence of estrogen.

As a woman ages, atrophy causes the vagina to shorten and the mu cous lining to become thin, dry, less elastic, and pale as a result of decreased vascularity. In addition, the pH of vaginal secretions increases, making the vaginal environment more alkaline The type of flora also changes, increasing the older woman’s chance of vaginal infections

Urinary system—Atrophic cystitis due to the effects of decreased estrogen levels on bladder mucosa and related structures may cause pyuria, dysuria, and urinary frequency, urgency, and incontinence. Urethral carbuncles from loss of urethral tone and mucosal thinning may cause dysuria, meatal tenderness, and hematuria.

Mammary system—Breast size decreases.

Integumentary system—The patient may experience loss of skin elasticity and turgor due to estrogen deprivation, loss of pubic and axillary hair and, occasionally, slight alopecia.

Autonomic nervous system—The patient may exhibit hot flashes and night sweats (in 75% of women), vertigo, syncope, tachycardia, dyspnea, tinnitus, emotional disturbances (irritability, nervousness, crying spells, fits of anger), and exacerbation of pre-existing depression, anxiety, and compulsive, manic, or schizoid behavior.

Menopause may also induce atherosclerosis, and a decrease in estrogen level contributes to osteoporosis.

Ovarian activity in younger women is believed to provide a protective effect on the cardiovascular system, and the loss of this function at menopause may partly explain the increased death rate from myocardial infarction in older women. Also, estrogen has been found to increase levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

DIAGNOSIS

Patient history and typical clinical features suggest menopause. A Papanicolaou (Pap) test may show the influence of estrogen deficiency on vaginal mucosa. Radioimmunoassay (RIA) may be performed, but because of the expense involved, it isn’t necessary to confirm a diagnosis of menopause. If done, RIA shows the following blood hormone levels:

estrogen: 0 to 14 ng/dl

plasma estradiol: 15 to 40 pg/ml

estrone: 25 to 50 pg/ml

RIA also shows the following urine values:

estrogen: 6 to 28 mcg/24 hours

pregnanediol (urinary secretion of progesterone): 0.3 to 0.9 mg/24 hours

Follicle-stimulating hormone production may increase as much as 15 times its normal level; luteinizing hormone production, as much as 5 times.

Pelvic examination, endometrial biopsy, and dilatation and curettage may rule out organic disease in patients with abnormal menstrual bleeding.

TREATMENT

Menopause is a natural process that doesn’t require treatment unless menopausal symptoms, such as hot flashes or vaginal dryness, are particularly bothersome. Hormonal agents for patients with a uterus include estrogen with progesterone to prevent endometrial cancer. If the patient doesn’t have a uterus, progesterone isn’t necessary.

The Women’s Health Initiative has led physicians to revise their recommendations regarding hormone replacement therapy (HRT). Health risks (increased incidence of breast cancer, heart attacks, strokes, and blood clots) outweigh the health benefits (decreased osteoporosis) for women taking both estrogen and progesterone. If symptoms are severe, HRT may be considered for short-term use (2 to 4 years) to reduce vaginal dryness, hot flashes, and other symptoms. If this is used, frequent pelvic examinations, Pap smears, physical examinations, breast examinations, and mammograms are indicated to reduce the risks of estrogen replacement therapy while still gaining the treatment’s benefits.

Medications may be prescribed to help with mood swings, hot flashes, and other symptoms. These include low doses of antidepressants, such as paroxetine, venlafaxine, and fluoxetine, or clonidine, which is normally used to control high blood pressure.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Provide the patient with all the facts about HRT, if used. Make sure she realizes the need for regular monitoring.

Before HRT begins, have the patient undergo a baseline physical examination, Pap test, and mammogram.

Advise the patient not to discontinue contraceptive measures until cessation of menstruation has been confirmed.

Tell the patient to immediately report vaginal bleeding or spotting after menstruation has ceased.

Discuss alternatives to HRT, which can help with the discomforting symptoms of menopause:

Advise the patient to dress lightly and in layers.

Tell the patient to avoid caffeine, alcohol, and spicy foods. Encourage soy-based foods.

Instruct the patient to practice slow, deep breathing whenever a hot flash starts to come on, or to try other relaxation techniques, such as yoga, tai chi, or meditation. Tell her that acupuncture may also be helpful.

If the patient is in a sexually active relationship, tell her to remain sexually active to preserve vaginal elasticity. Water-based lubricants can be used during sexual intercourse to decrease dryness.

Instruct the patient that Kegel exercises may be performed daily to strengthen the vaginal and pelvic muscles.

Female infertility

Primary infertility is the inability to conceive after regular intercourse for at least 1 year without contraception. Secondary infertility occurs in couples who have previously been pregnant at least once, but are unable to achieve another pregnancy. About 30% to 40% of all infertility is attributed to the male, and 40% to 50% to the female; about 10% to 30% is due to a combination of male and female factors. Following extensive investigation and treatment, about 50% of these infertile couples achieve pregnancy. Of the 50% who don’t, 10% have no pathologic basis for infertility; the prognosis for this group becomes extremely poor if pregnancy isn’t achieved within 3 years.

CAUSES AND INCIDENCE

The causes of female infertility may be functional, anatomic, or psychosocial:

Functional causes: complex hormonal interactions determine the normal function of the female reproductive tract and require an intact hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis—the system that stimulates and regulates the hormone production necessary for normal sexual development and function. Any defect or malfunction of this axis can cause infertility due to insufficient gonadotropin secretions (both luteinizing hormone [LH] and follicle-stimulating hormone). The ovary controls, and is controlled by, the hypothalamus through a system of negative and positive feedback mediated by estrogen production. Insufficient gonadotropin levels may result from infections, tumors, or neurologic disease of the hypothalamus or pituitary gland. Hypothyroidism also impairs fertility.

Anatomic causes include the following:

Ovarian factors are related to anovulation and oligo-ovulation (infrequent ovula tion) and are a major cause of infertility.

Pregnancy or direct visualization provides irrefutable evidence of ovulation. Presumptive signs of ovulation include regular menses, cyclic changes reflected in basal body temperature readings, postovulatory progesterone levels, and endometrial changes due to the presence of progesterone. Absence of presumptive signs suggests anovulation. Ovarian failure, in which no ova are produced by the ovaries, may result from ovarian dysgenesis or premature menopause. Amenorrhea is often associated with ovarian failure. Oligoovulation may be due to a mild hormonal imbalance in gonadotropin production and regulation and may be caused by polycystic ovary syndrome or abnormalities in the adrenal or thyroid gland that adversely affect hypothalamic-pituitary functioning.

Uterine fibroids or uterine abnormalities rarely cause infertility; however, uterine abnormalities may include congenitally absent uterus, bicornuate or double uterus, leiomyomas, or Asherman’s syndrome, in which the anterior and posterior uterine walls adhere because of scar tissue formation.

Tubal and peritoneal factors are due to faulty tubal transport mechanisms and unfavorable environmental influences affecting the sperm, ova, or recently fertilized ovum. Tubal loss or impairment may occur secondary to ectopic pregnancy.

Frequently, tubal and peritoneal factors result from anatomic abnormalities: bilateral occlusion of the tubes due to salpingitis (resulting from gonorrhea, tuberculosis, or puerperal sepsis), peritubal adhesions (resulting from endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease [PID], diverticulosis, or childhood rupture of the appendix), and uterotubal obstruction (due to tubal spasm).

Cervical factors may include malfunctioning cervix that produces deficient or excessively viscous mucus and is impervious to sperm, preventing entry into the uterus. In cervical infection, viscous mucus may contain sper micidal macrophages. Cervical antibodies have also been found to immobilize sperm.

Psychosocial problems probably account for relatively few cases of infertility. Occasionally, ovulation may stop under stress due to failure of LH release. The frequency of intercourse may be related. More often, however, psychosocial problems result from, rather than cause, infertility.

About 10% to 20% of couples will be unable to conceive after 1 year of attempting to become pregnant. Healthy couples who are younger than age 30 and having intercourse regularly only have a 25% to 30% change of getting pregnant each month. A woman’s peak fertility is in her early 20s. As a woman ages beyond 35 (and particularly beyond 40), the likelihood of conception is less than 10% per month.

COMPLICATION

▪ Depression

DIAGNOSIS

Inability to achieve pregnancy after having regular intercourse without contraception for at least 1 year suggests infertility. (In women older than age 35, many clinicians use 6 months rather than 1 year as a cutoff point.)

Diagnosis requires a complete physical examination and health history, including specific questions on the patient’s reproductive and sexual function, past diseases, mental state, previous surgery, types of contraception used in the past, and family history. Irregular, painless menses may indicate anovulation. A history of PID may suggest fallopian tube blockage. Sometimes PID is silent, and no history may be known.

The following tests assess ovulation:

Basal body temperature graph shows a sustained elevation in body temperature postovulation until just before the onset of menses, indicating the approximate time of ovulation.

Endometrial biopsy, done on or about day 26, provides histologic evidence that ovulation has occurred. However, endometrial biopsy is retrospective, which diminishes its utility.

Progesterone blood levels, measured when they should be highest, can show a luteal phase deficiency or presumptive evidence of ovulation.

The following procedures assess structural integrity of the fallopian tubes, the ovaries, and the uterus:

Urinary LH kits, available without a prescription, can sensitively detect the LH surge about 24 hours preovulation, allowing couples to time coitus.

Hysterosalpingography provides radiologic evidence of tubal obstruction and uterine cavity abnormalities by injecting radiopaque contrast fluid through the cervix.

Male-female interaction studies include the following:

Postcoital test (Sims-Huhner test) examines the cervical mucus for motile sperm cells following intercourse that takes place at midcycle (as close to ovulation as possible).

Immunologic or antibody testing detects spermicidal antibodies in the female’s sera.

Several things can be done to help prevent infertility. Advise your patient about the following:

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs)

Gonorrhea and chlamydia are the two most common STI-related causes of infertility. These STIs can lead to ectopic pregnancy and scarring of the fallopian tubes. Practicing safe sex can help prevent STIs.

Endometriosis

The early detection and treatment of endometriosis can eliminate the scarring that leads to infertility.

Lifestyle changes

Advise your patient to get regular moderate exercise, not intense exercise, which can lead to amenorrhea. Advise her to maintain adequate weight. Being underweight or overweight can affect hormones. Advise her to avoid using alcohol and illegal drugs, and if she smokes, suggest that she quit; these substances may have an effect on fertility. Suggest that she discuss with her practitioner the use of prescription over-the-counter drugs and the possible effects they may have on fertility.

TREATMENT

Treatment depends on identifying the underlying abnormality or dysfunction within the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. In hyperactivity or hypoactivity of the adrenal or thyroid gland, hormone therapy is necessary; progesterone deficiency requires progesterone replacement. Anovulation necessitates treatment with clomiphene, human menopausal gonadotropins, or human chorionic gonadotropin; ovulation usually occurs several days after such administration. If mucus production decreases (an adverse effect of clomiphene), small doses of estrogen to improve the quality of cervical mucus may be given concomitantly; however, such intervention remains unproven.

Surgical restoration may correct certain anatomic causes of infertility such as fallopian tube obstruction. Surgery may also be necessary to remove tumors located within or near the hypothalamus or pituitary gland. Endometriosis requires drug therapy (danazol or medroxyprogesterone, gonadotropin-releasing hormone [GnRH] analogues or noncyclic administration of hormonal contraceptives), surgical removal of areas of endometriosis, or a combination of both.

Other options, often controversial and involving emotional and financial cost, include surrogate mothering, frozen embryos, or in vitro fertilization (IVF). In view of the good success rate of IVF (about 20%), IVF may be used instead of surgery in many cases.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Management includes providing the infertile couple with emotional support and information about diagnostic and treatment techniques. (See Preven ting infertility.)

An infertile couple may suffer loss of self-esteem; they may feel angry, guilty, or inadequate, and the diagnostic procedures for this disorder may intensify their fear and anxiety. You can help by explaining these procedures thoroughly. Above all, encourage the patient and her partner to talk about their feelings, and listen to what they have to say with a nonjudgmental attitude.

If the patient requires surgery, tell her what to expect postoperatively; this, of course, depends on which procedure is to be performed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree