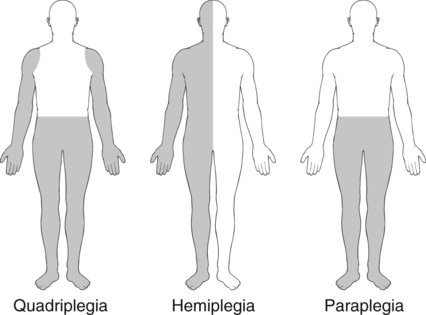

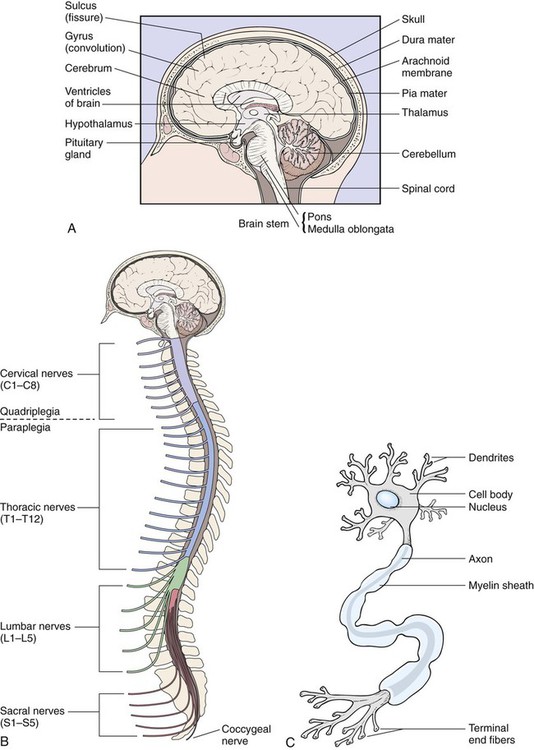

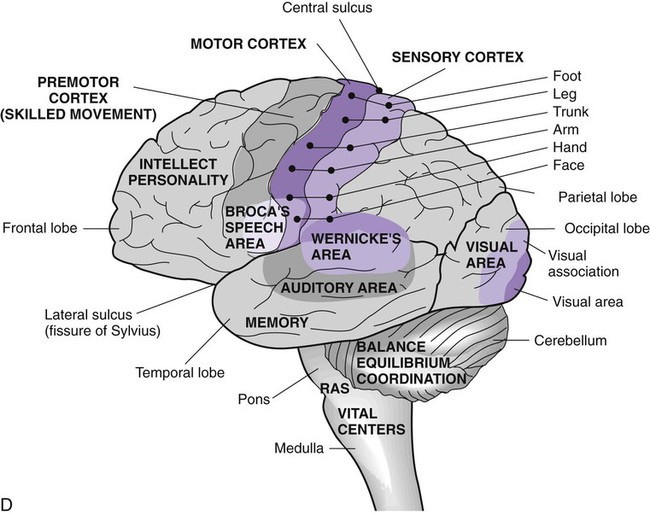

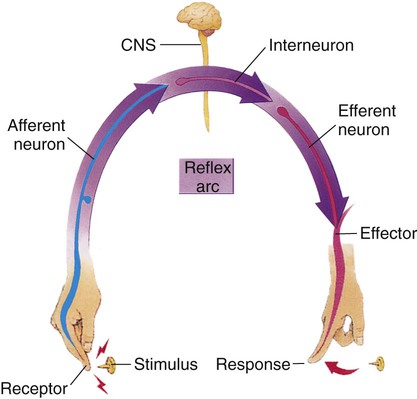

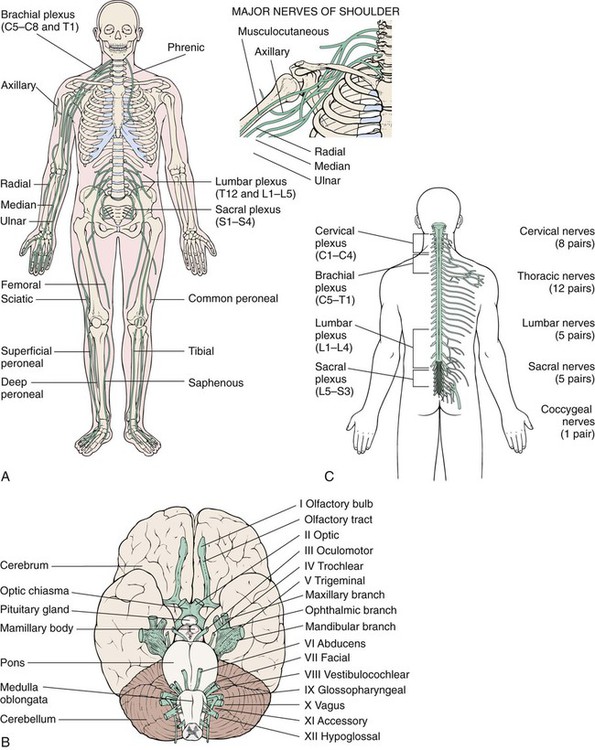

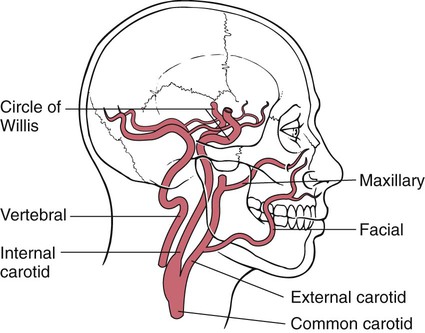

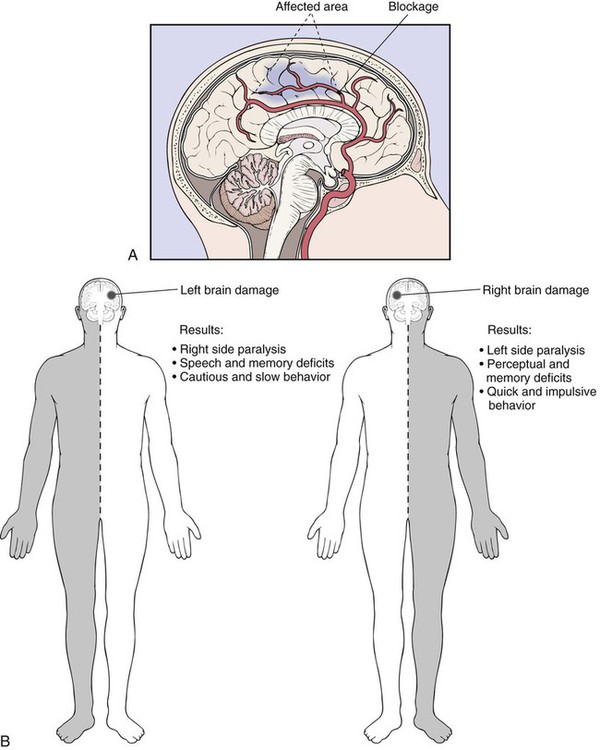

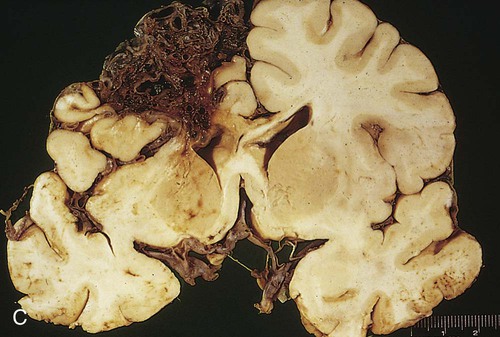

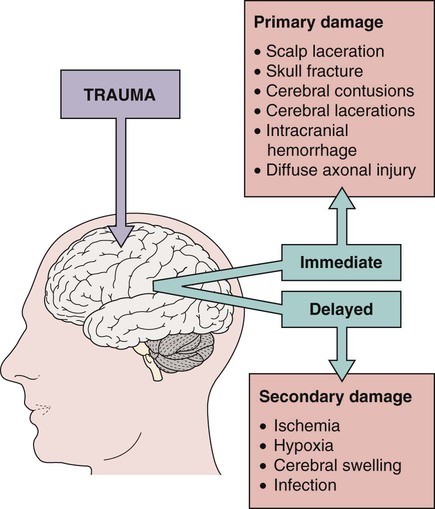

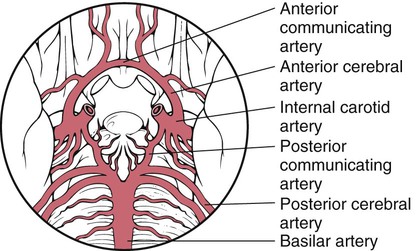

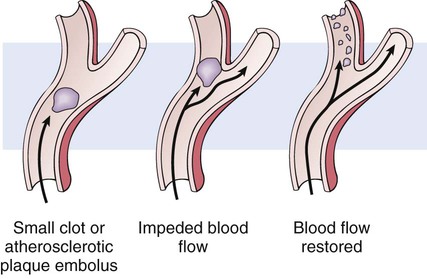

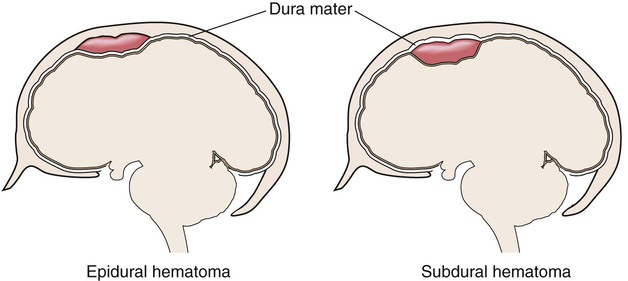

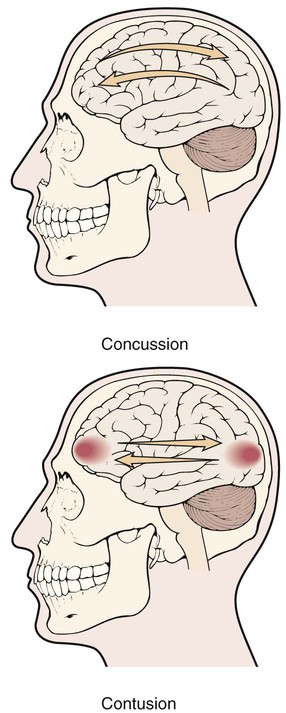

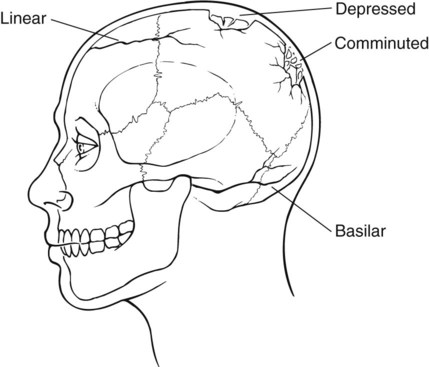

After studying Chapter 13, you should be able to: 1. Name the main components of the nervous system. 2. List some of the problems to which the nervous system is susceptible. 3. Describe how data are collected during a neurologic assessment. 4. Name the common symptoms and signs of a cerebrovascular accident (CVA). 5. Name the three vascular disorders that may cause a CVA. 6. Define a transient ischemic attack (TIA). 7. Distinguish between (a) epidural and subdural hematomas and (b) cerebral concussion and cerebral contusion. 8. Describe three mechanisms of spinal injuries. 9. Name the goals of treatment of spinal cord injuries. 10. Explain the neurologic consequences of the deterioration or rupture of an intervertebral disk. 11. Describe the symptoms of a migraine. 12. Explain why cephalalgia sometimes is considered a symptom of underlying disease. 13. Describe first aid for seizures. 14. Explain how the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease are controlled. 15. Describe the progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). 16. Discuss restless legs syndrome. 17. Discuss transient global amnesia. 18. Distinguish between trigeminal neuralgia and Bell’s palsy. 19. List the diagnostic tests used for meningitis and explain how the causative organism is identified. 20. Name the common causes of encephalitis. 21. Explain the pathologic course of Guillain-Barré syndrome. The nervous system is a complex, sophisticated, and elaborate network of many interlaced nerve cells (neurons) that make up the brain (Figure 13-1, A), the spinal cord (Fig 13-1, B), and the nerves. Electrical impulses are carried throughout the body by the neurons (Figure 13-1, C, and Figure 13-2). This entire system regulates and coordinates the body’s activities and produces responses to stimuli, which help the body adjust to changes in its environment, both internal and external. The nervous system is composed of two divisions: the central nervous system (CNS) and the peripheral nervous system (PNS). The CNS includes the brain and spinal cord. Its function is to process and store sensory and motor information and to govern the state of consciousness. For example, the structures of the brain that control the intellectual functions of thinking, willing, remembering, and deciding, and those that control personality, are located in the frontal lobe of the cerebrum. Coordination, equilibrium, and posture are coordinated in the cerebellum area of the brain. The hypothalamus regulates the secretion of hormones from the pituitary gland and regulates many visceral activities. Five pairs of the 12 cranial nerves originate in the medulla oblongata, an extension of the spinal cord; the medulla also contains vital centers that help regulate heart rate, blood pressure, and respiration. All the sensory and motor nerve fibers pass through the medulla oblongata, connecting the brain and the spinal cord. The spinal cord, a continuation of the medulla oblongata, extends to the first lumbar vertebra. It is divided into 31 segments, each giving rise to a pair of spinal nerves that act like a telephone switchboard, or reflex center, carrying impulses to and from the brain (Figure 13-1, D). The vast network of nerves throughout the rest of the body is part of the PNS (Figure 13-3, A). Peripheral nerves connect with the spinal cord at many levels, and the information (impulses) they carry travels to and from the brain and spinal cord. Sensory (afferent) nerves transmit impulses from parts of the body (e.g., skin, eye, ear, and nose) to the spinal cord and brain. Motor (efferent) nerves transmit impulses away from the CNS and produce responses in muscles and glands. The PNS contains 12 pairs of cranial nerves (Figure 13-3, B), and 31 pairs of spinal nerves (Figure 13-3, C). Refer to Figure 6-12, Dermatomes, to compare innervations of spinal nerves E13-3 and the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves. The sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves make up the autonomic nervous system (ANS), which regulates the involuntary muscle movements and glandular actions of the body. The PNS also controls all conscious activities, which greatly affect unconscious processes, such as the heart rate and bowel functions. E13-4 Four major blood vessels on each side of the head supply the brain with essential oxygen and nutrients. The carotid arteries (two internal and two external) originate from the two common carotid arteries and are located in the anterior portion of the neck; the two vertebral arteries, located within the vertebral column (Figure 13-4), join with the two anterior and posterior cerebral arteries and the two anterior and posterior communicating arteries to form the brain’s vascular system in a roughly circular configuration of arteries known as the circle of Willis. Branches from the circle of Willis supply blood to all portions of the brain (Figure 13-5). Areas of the brain that depend on a single branch for survival are especially vulnerable to any disruption in the blood flow (e.g., thrombus or embolus). (See “Vascular Disorders” section.) • Motor disturbances, other disturbances of movement, or paralysis • Altered levels of consciousness • Sensory disturbances or numbness CVAs are the number one cause of adult disability. Because of the inadequate blood supply, the physical and mental functions controlled by the affected area of the brain fail to operate properly (Figure 13-6, A). The symptoms and signs of a stroke reflect the portion of the brain affected (Figure 13-6, B). Common stroke symptoms include the following: • Sudden aphasia, dysphasia, or difficulty understanding language • Sudden weakness, numbness, or paralysis of the face, including one-sided drooping mouth and eyelid (hemiparesis) • Sudden confusion or impaired consciousness • Sudden loss of vision, blurred vision, unequal pupils, or diplopia • Sudden onset of dizziness, loss of balance, or loss of coordination A CVA is usually the result of one of three types of vascular disorders: occlusion of an artery caused by an atheroma; sudden obstruction by an embolus, including a cerebral thrombosis (clot), embolism (moving clot), or other moving emboli; and a cerebral bleed. E13-6 These vascular disorders most often are caused by atherosclerosis (see “Atherosclerosis” section in Chapter 10) and hypertension (high blood pressure). Strokes also can result from blood disorders, arrhythmias, systemic diseases (e.g., diabetes mellitus and syphilis), hyperlipidemia, rheumatic heart disease, or head trauma. A high-fat diet, lack of exercise, cigarette smoking, obesity, and a family history of atherosclerotic disease are contributing factors. With a cerebral hemorrhage, the cerebral artery is not blocked but instead ruptures, flooding the surrounding brain tissue with blood. E13-7 The initial effects of a hemorrhage may be more severe than those of a thrombosis or embolism, and the long-term effects are much more serious (Figure 13-6, C). (Refer to the Enrichment box on Arteriovenous Malformations [AVM].) The most common cause of TIA is a piece of plaque, formed by atherosclerosis, which breaks away from the wall of an artery or heart valve and travels to the brain (Figure 13-7). This is known as an embolus or moving clot. Platelet fibrin emboli from an arterial ulcer are often the causative factor. Arterial vascular spasms and minute blood clots also may be etiologic factors. Unlike strokes, TIAs do not normally cause permanent damage to the brain tissue. Head trauma usually results in brain injury. Ranging from mild to life-threatening or fatal, traumatic brain injury may be the result of several types of insults to the head. Included in the forms of traumatic brain injury are concussions, contusions, closed head injuries, open head injuries, linear fractures, comminuted fractures, compound fractures, and contrecoup injuries. Concussions, contusions, and injuries where the cranial vault is not violated are types of closed head injuries; fractures to the cranial vault are open head injuries and include linear, depressed, comminuted, compound, and basilar skull fractures (see Figure 13-11). E13-10 An epidural hematoma is a collection or mass of blood that forms between the skull and the dura mater, the outermost of the three meningeal layers covering the brain. With a subdural hematoma, the blood collects or pools between the dura mater and the arachnoid membrane, the second meningeal membrane (Figure 13-8). E13-11 (S06.6X0(7th digit)-S06.6X9(7th digit) = 10 codes of specificity) S06.4X0A (Epidural hemorrhage without loss of consciousness, initial encounter) (S06.4X0(7th digit)-S06.4X9(7th digit) = 10 codes of specificity) S06.5X0A (Traumatic subdural hemorrhage without loss of consciousness, initial encounter) (S06.5X0(7th digit)-S06.5X9(7th digit) = 10 codes of specificity) A cerebral concussion is an injury resulting from impact with a blunt object, either by receiving a blow to the head or by falling. This results in a disruption of the normal electrical activity in the brain, but the brain itself usually is not permanently injured (Figure 13-9). Mild traumatic brain injury (MTBI) is a term that can be applied to this injury. A contusion of the brain is caused by a blow to the head or impacting against a hard surface, as occurs in an automobile accident. The twisting or shearing force against the two hemispheres of the brain that occurs when colliding with the cranial bones may damage structures deep within the brain (see Figure 13-9). A contusion often is associated with a skull fracture. This traumatic brain injury may be observed in child, spouse, partner, or elder abuse. A fractured skull occurs with a break or fracture in one of the bones of the cranium (Figure 13-11). When the skull bones are depressed or torn loose, they are pushed below the normal surface of the skull. When a portion of the skull is broken and is pushed in on the brain, causing injury, it is said to be a depressed skull fracture (see Figure 13-11). The symptoms depend on the site of the fracture. For example, a bone fragment pressing on the motor area of the brain may cause hemiplegia (Figure 13-12). Characteristically, symptoms from a depressed fracture are not progressive. They tend to remain static until the depressed bone is elevated and the pressure is relieved. Epilepsy is a common complication of depressed skull fractures (see Figure 13-11 for additional types of skull fractures)

Neurologic Diseases and Conditions

Orderly Function of the Nervous System

Vascular Disorders

Cerebrovascular Accident (Stroke)

Symptoms and Signs

Etiology

Transient Ischemic Attack

Etiology

Head Trauma

Epidural and Subdural Hematomas

Description

ICD-9-CM Code 852 (Subarachnoid, subdural and extradural hemorrhage, following injury)

ICD-9-CM Code 852 (Subarachnoid, subdural and extradural hemorrhage, following injury)

ICD-10-CM Code S06.6X0A (Traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage without loss of consciousness, initial encounter)

ICD-10-CM Code S06.6X0A (Traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage without loss of consciousness, initial encounter)

Cerebral Concussion

Etiology

Cerebral Contusion

Etiology

Depressed Skull Fracture

Description

Symptoms and Signs