Overview

Neoplasia is new growth. The terms benign and malignant correlate to the course of the neoplasm. Benign neoplasms stay localized in one place; malignant neoplasms invade surrounding tissue and, in most cases, can metastasize to distant organs. To become neoplastic, a normal cell must develop mutations that allow it to no longer obey boundaries of adjacent cells, thus allowing for uncontrolled growth, and the neoplasm must be able to produce its own blood supply. If the neoplasm is malignant, the cells must also gain the ability to invade the basement membrane and surrounding tissue, enter the blood stream, and spread to and grow within distant organs.

This chapter will discuss the basic terms associated with neoplasia, features used to distinguish benign neoplasms from malignant neoplasms, epidemiology and etiology of neoplasms, effects of tumors (including paraneoplastic syndromes), basic carcinogenesis (including proto-oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes), diagnosis (including tumor markers and immunohistochemistry), and basic grading and staging.

Terminology of Neoplasia

Overview: The terms tumor, nodule, and mass are nonspecific terms that refer to an abnormal proliferation of cells. The term neoplasm means new growth and does not imply benign or malignant (i.e., there are benign neoplasms, and there are malignant neoplasms).

- Adenoma: Benign neoplasm derived from glandular cells.

- Carcinoma: Malignant neoplasm derived from epithelial cells (Figures 4-1 and 4-2).

- Sarcoma: Malignant neoplasm derived from mesenchymal cells (e.g., fat, muscle).

- Lymphoma: Malignant neoplasm derived from lymphocytes.

- Melanoma: Malignant neoplasm derived from melanocytes.

- Germ cell tumor: Malignant neoplasm derived from germ cells.

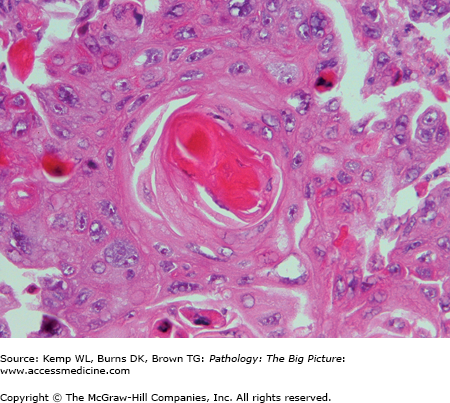

Figure 4-1.

Squamous cell carcinoma. Squamous cell carcinoma is one of the major forms of carcinoma, occurring within many organs including the mouth, upper respiratory tract, and lungs. In the center of the photomicrograph is a keratin pearl, a characteristic feature of a well or moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. Hematoxylin and eosin, 400×.

- Examples: Adenoma (benign neoplasm of glandular epithelium), fibroadenoma (benign neoplasm of the breast), and leiomyoma (benign neoplasm of smooth muscle).

- Some exceptions: Hepatoma (malignant neoplasm of liver), melanoma (malignant neoplasm of melanocytes), mesothelioma (malignant neoplasm of mesothelial cells), and seminoma (malignant germ cell neoplasm of testis).

- Examples: Adenocarcinoma (malignant neoplasm of glandular tissue), rhabdomyosarcoma (malignant neoplasm of skeletal muscle), and leiomyosarcoma (malignant neoplasm of smooth muscle).

- Differentiation: How histologically similar to the normal tissue the neoplasm is (i.e., how analogous the neoplastic cells look to the tissue type from which they arose)—terms used are well differentiated, moderately differentiated, or poorly differentiated (Figures 4-3 and 4-4). Differentiation is a subjective determination made by the pathologist.

- Anaplasia: Lack of differentiation.

- Dysplasia: Disordered growth of epithelium. There is a loss of cellular uniformity and architectural orientation. The cells may have an increased number of mitotic figures. Dysplasia does not necessarily form a mass or tumor. In many cases, dysplasia is a precursor of malignancy, but dysplasia does not always progress to malignancy. Dysplasia can be reversible, if the inciting agent is removed (Figure 4-5).

- Carcinoma in situ: Full-thickness dysplasia of the epithelium.

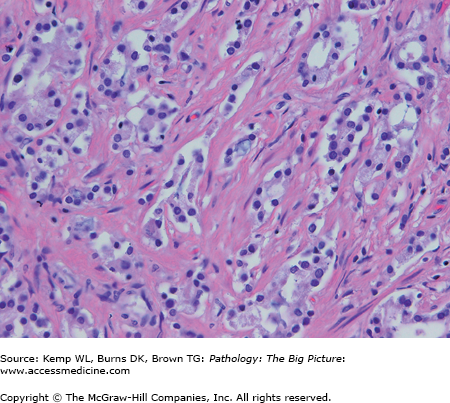

Figure 4-3.

Well to moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. The cell of origin for this tumor (squamous cell) can be determined from the histologic appearance of the tumor. The arrow indicates the interconnecting nature of the cells. Keratin pearls and intercellular bridges are characteristic of well to moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. Hematoxylin and eosin, 400×.

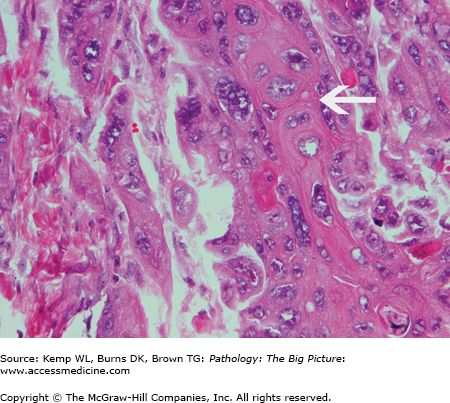

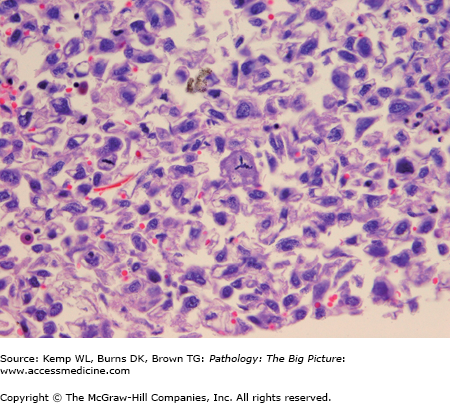

Figure 4-4.

Poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. Unlike the neoplasm illustrated in Figure 4-3, the cell of origin for this tumor cannot be adequately determined from the histologic appearance alone. No keratin pearls or intercellular bridges are apparent. Hematoxylin and eosin, 200×.

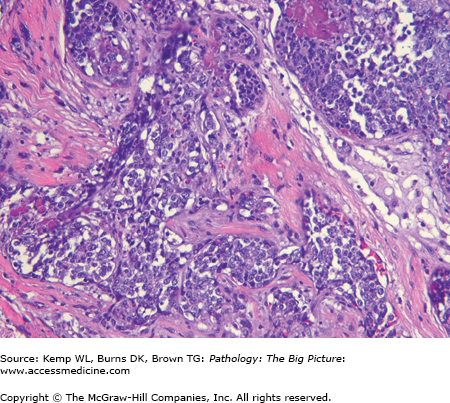

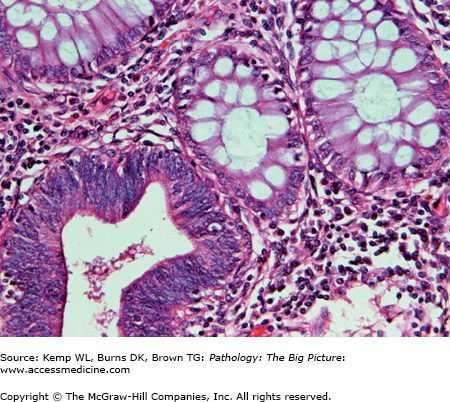

Figure 4-5.

Dysplasia. This photomicrograph illustrates colonic dysplasia in a tubular adenoma. The gland in the left lower corner is dysplastic. The epithelial cells have features of neoplasia (i.e., increased cellularity, hyperchromatic nuclei, and mitotic figures). The remainder of the glands shown in the photomicrograph are histologically normal. Dysplasia is often a precursor of malignancy. Hematoxylin and eosin, 400×.

- Hamartoma: A disorganized collection of tissue, with the tissue composing the mass being tissue that is normally found in the organ in which the mass occurred; a hamartoma is not a neoplasm.

- Choristoma: A mass composed of ectopic tissue (i.e., otherwise fairly normal tissue located at a site where it normally is not found). A choristoma is not a neoplasm.

- Polyp: Mass projecting from a mucosal surface. A polyp is a descriptive term; the mass causing the polyp may or may not be a neoplasm.

Features Used to Distinguish Benign Neoplasms from Malignant Neoplasms

Histologic features are reliable indicators of malignancy in many organs, although in some sites (e.g., the endocrine system), histologic features do not always distinguish benign neoplasms from malignant neoplasms (Figures 4-6 and 4-7). The histologic features of malignancy are listed below.

- Pleomorphism: Variation in nuclear and cytoplasmic shape between cells.

- Abnormal mitotic figures and increased numbers of mitotic figures.

- Hyperchromasia: Increased basophilia of the nucleus.

- Hypercellularity, with a loss of normal polarity.

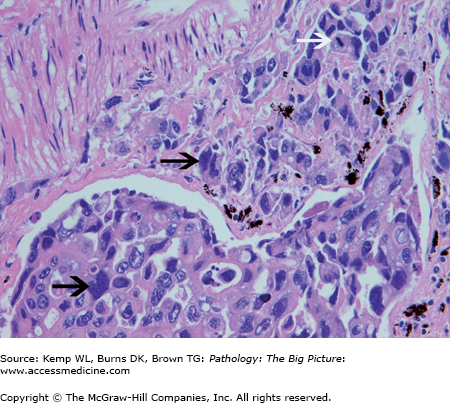

Figure 4-6.

Cellular features of malignancy. The photomicrograph illustrates an anaplastic neoplasm with hypercellularity, nuclear hyperchromasia (black arrows), and mitotic figures (white arrow). However, in most cases, cellular features alone cannot distinguish a benign neoplasm from a malignant neoplasm. Hematoxylin and eosin, 400×.

Figure 4-7.

Abnormal mitotic figure. In the center of this photomicrograph is a neoplastic cell with a tripolar mitotic figure. Although increased numbers of mitotic figures can be seen in non-neoplastic cells (e.g., normal epithelial cells and reactive processes), abnormal mitotic figures usually indicate a neoplastic process, and most often a malignant process. Hematoxylin and eosin, 400×.

- Benign neoplasms tend to grow slower; malignant neoplasms tend to grow more quickly, often at a rate corresponding to their degree of anaplasia.

- Growth fraction: The proportion of neoplastic cells in the proliferative phase. At the point when most malignant tumors are clinically detected, the growth fraction is usually less than 20% (i.e., most neoplasms have their most rapid rate of growth prior to detection).

- Histologic features and rate of growth alone cannot always distinguish between benign and malignant neoplasms. The two features that reliably distinguish benign from malignant neoplasms are (1) invasion, or the infiltration of tumor cells into surrounding organs; and (2) metastases, or the spread of tumor cells to distant organs through the blood, which is characteristic of sarcomas, or through the lymphatics, which is characteristic of carcinomas (Figure 4-10).

- Some malignancies do not metastasize (e.g., gliomas and basal cell carcinoma of the skin), but they do invade.

- Overall, 30% of malignant solid tumors have metastases at the time they are clinically detected.

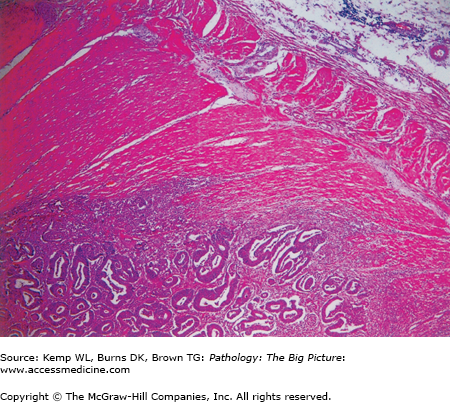

Figure 4-8.

Colonic adenocarcinoma with invasion into the muscularis propria. This low-power photomicrograph of the colonic muscularis propria illustrates invasion into the wall by a colonic adenocarcinoma. Invasion as well as metastases is a definite indicator of a malignant neoplasm. Hematoxylin and eosin, 40×.

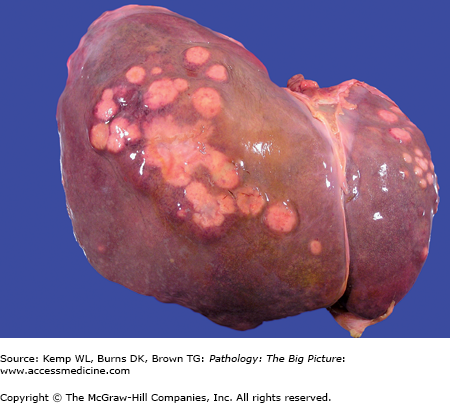

Figure 4-9.

Colonic adenocarcinoma metastases to the liver. The tan-yellow nodules in the left and right lobes of this liver are metastases from a colonic adenocarcinoma. Metastasis as well as invasion is a definite indicator of a malignant neoplasm. The most common malignant neoplasm of the liver is a metastasis; however, the most common malignancy that metastasizes to the liver is a pulmonary neoplasm.

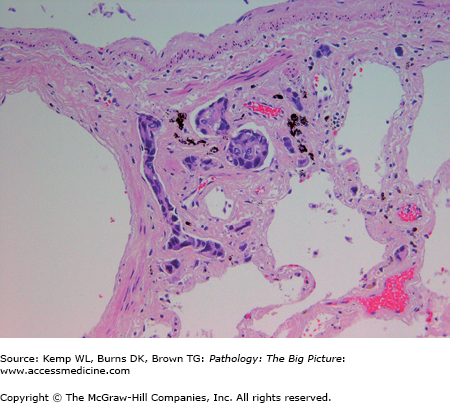

Figure 4-10.

Lymphatic invasion by a carcinoma. The clusters of neoplastic cells in the center of this photomicrograph represent lymphatic invasion by a carcinoma (the lymphatics are within the lung). Malignant neoplasms most commonly metastasize via lymphatic or hematogenous routes. Lymphatic metastases are most commonly associated with carcinomas, and hematogenous metastases are most commonly associated with sarcomas. Hematoxylin and eosin, 400×.

Cancer Stem Cells

Epidemiology and Etiology of Cancer

Overview: In descending order of frequency, the most frequently diagnosed neoplasms (i.e., incidence) in males are carcinomas of the prostate, lung, and colon. In females, the most frequently diagnosed neoplasms are carcinomas of the breast, lung, and colon. Mortality due to neoplasms varies slightly from the incidence, with carcinomas of the lung accounting for the most frequent cause of cancer deaths in males and females, followed by prostatic and colonic neoplasms in males and breast and colonic carcinomas in females.

Although the development of many neoplasms is a sporadic event, certain heritable conditions predispose to the development of malignancy. These hereditary causes of neoplasms may be grouped into autosomal dominant neoplasia syndromes (Table 4-1) and defective DNA repair syndromes (Table 4-2), most of which are autosomal recessive. Importantly, although certain mutations are associated with the development of certain malignancies, one mutation alone is NOT enough to result in the development of a neoplasm.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree