Patient Story

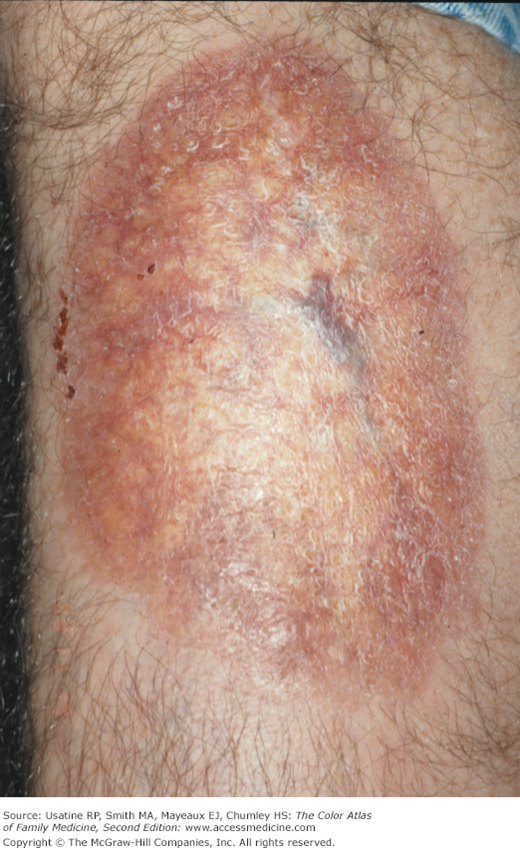

A 30-year-old woman presents with discoloration on both lower legs. She has no personal history of diabetes; however, type 2 diabetes does run in her family. Visible inspection of the lesions is highly suggestive of necrobiosis lipoidica (NL) (Figure 222-1). There is hyperpigmentation, yellow discoloration, atrophy, and telangiectasias. The patient is not overweight and had no symptoms of diabetes. Her blood sugar at this visit is 142 after eating lunch 1 hour prior to testing. The following day, the patient’s fasting blood sugar is 121, with a glycosylated hemoglobin of 6.1. The patient is informed of her borderline diabetes, and diet and exercise are prescribed. She is disturbed by her skin appearance and chooses to try a moderate-strength topical corticosteroid for treatment.

Introduction

Epidemiology

- NL is a rare condition that occurs in approximately 1% (0.3% to 2.3%) of patients with DM.1–4

- NL primarily affects women (80%), particularly those with type 1 DM, but it can occur with type 2 DM.1,2 Approximately 75% of patients with NL have or will develop DM.5

- Average age of onset is 34 years.1,2

- In a study comparing young patients with type 1 DM (N = 212, ages 2 to 22 years) with sex- and age-matched control patients, most (68% vs. 26.5% of controls) had at least 1 cutaneous disorder, with 2.3% versus 0% of control patients having NL.4

- NL has also been reported in patients with Hashimoto thyroiditis.3

- Cases of familial NL not associated with DM have also been reported.6

Etiology and Pathophysiology

- The cause of NL remains unknown.

- Angiopathy leading to thrombosis and occlusion of the cutaneous vessels has been implicated in its etiology. However, microangiopathic changes are less common in lesions on areas other than the shins and, therefore, are not necessary for developing the lesions.2 In addition, one study found that NL lesions exhibited significantly higher blood flow rates than areas of unaffected skin close to the lesions.7

- Antibodies and C3 have been found at the dermal-epidermal junction, suggesting vasculitis.

- The presence of fibrin in these lesions associated with palisading histiocytes may indicate a delayed hypersensitivity reaction.

- In a study using focus-floating microscopy, a modified immunohistochemical technique was developed to detect Borrelia spirochetes. Borrelia was detected in 75% of NL lesions overall and 92.7% of inflammatory-rich (38 of 41) versus inflammatory-poor (4 of 15, 26.7%) cases.8 The authors posit that these findings indicate a potential role for Borrelia burgdorferi or other similar strains in the development of or trigger for NL.

Diagnosis

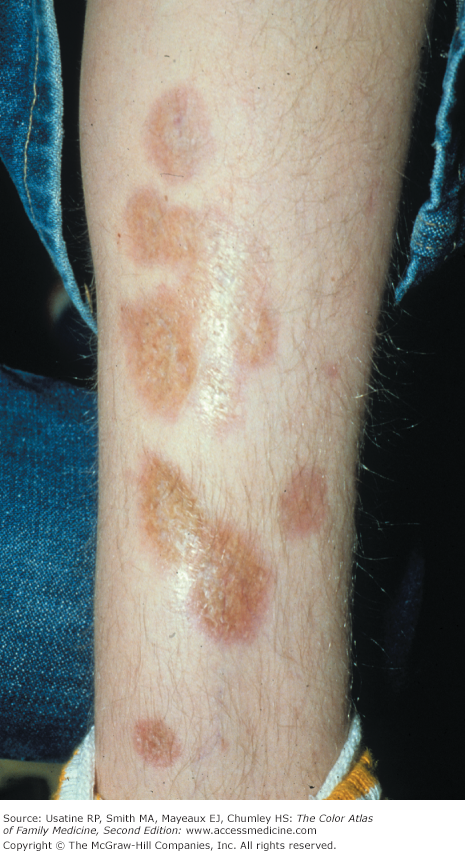

- The lesions begin as erythematous papules or plaques in the pretibial area and become larger and darker with irregular margins and raised erythematous borders (Figures 222-1, 222-2, 222-3, and 222-4). The lesion’s center atrophies and turns yellow in color, appearing waxy (Figures 222-3, 222-4, and 222-5A).

- There is often a prominent brown color or hyperpigmentation visible (Figures 222-1, 222-2, 222-3, and 222-4).

- The lesions may ulcerate (occurs in approximately one-third) and become painful (Figure 222-5B).

- Telangiectasias and prominent blood vessels may be seen within the lesions (Figures 222-1, 222-2, 222-3, and 222-4).

- The yellow color may be because of lipid deposits or beta-carotene.

- The lesions are usually located on the shins (90%) (Figures 222-1, 222-2, 222-3, and 222-4).

- NL lesions have been reported on many skin areas, including the face, scalp, and penis.9,10

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree