Modified Hill Repair for Gastroesophageal Reflux

Donald E. Low

Madhankumar Kuppusamy

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is the most common gastrointestinal problem in humans. Currently, 44% of the U.S. population experience heartburn at least once per month. In addition, more money is spent on heartburn medication than any other drug class other than the cholesterol-lowering agents. The goal of antireflux surgery is to control the symptoms and the secondary complications of reflux. Of the four most popular antireflux operations (Nissen fundoplication, Belsey Mark IV, Toupet, and Hill procedures), the Hill procedure is the only operation that originated in the United States. Unlike the more common Nissen fundoplication, the Hill repair has undergone very little modification since its inception at the Virginia Mason Medical Center in Seattle by Dr. Lucius Hill in 1959. The unique feature of the Hill repair is the fact that the operation is based on reestablishing normal anatomy and the normal barriers to gastroesophageal (GE) reflux. These normal anatomic barriers include the presence of a segment of intra-abdominal esophagus, the GE flap valve apparatus, and a competent lower esophageal sphincter.

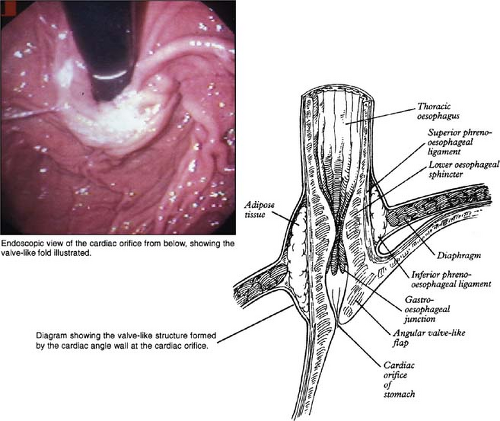

The least understood of these natural antireflux mechanisms and the one most amenable to surgical restoration is the gastroesophageal flap valve (Fig. 1). All three of the standard operations restore this anatomic structure; however, the Hill operation does so by restoring the normal posterior attachments and tightening the collar-sling musculature, thereby reestablishing the acute angle of His between the esophagus and stomach. Alternatively, the Nissen and Belsey operations restore the valve by horizontal or vertical fundoplications, which rely on more tenuous sutures between the fundus and the esophagus to stabilize the repair (see Fig. 2). This is an important adaptation to the original description of the Hill repair as it simplifies the repair sutures, as many surgeons were not willing to consider the increased difficulty and risk involved with dissecting out the celiac axis and median arcuate ligament.

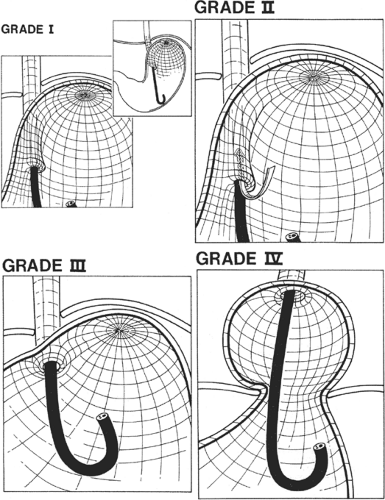

In our institution, healthy volunteers and those with documented GERD were examined with retroflexed inspection of the GE junction at the time of upper endoscopy. A grading system for the gastroesophageal valve was established from these findings (Fig. 3). This grading system has been shown to be highly accurate when used in preoperative assessment of the patients with GERD. It has also led to a greater understanding of esophageal anatomy as reflected by a cited alteration to the description of the gastroesophageal junction in Gray’s Anatomy (Fig. 1).

The Hill repair is a transabdominal repair and is the only repair that firmly anchors the GE junction in the abdomen to the strong crural musculature and underlying preaortic fascia. Originally, Dr. Hill recommended the placement of anchoring sutures through the median arcuate ligament. This aspect of the repair, which involves dissection and suture placement to the median arcuate ligament fascia, with its close proximity to the celiac axis, has intimidated surgeons who are not familiar with this anatomy and may explain why this operation has not been as widely accepted as the Nissen fundoplication. The median arcuate ligament is formed by the condensation of the preaortic fascia and is located on the anterior surface of the aorta just superior to the celiac axis. We have advocated an approach using the more easily accessible crural musculature with retrocrural preaortic fascia as the anchor for the repair.

Previous reports have suggested a higher incidence of dysphagia, gas bloat, and recurrent GERD after the Nissen repair. These concerns have often been associated with slipped repairs or recurrent hiatal hernia resulting from the lack of a strong posterior fixation of the GE junction. With the Hill procedure, any tendency of the repair to be pulled up into the chest is significantly reduced because of the dependable fixation of the GE junction within the abdominal cavity. This posterior fixation is particularly important in patients with

Barrett’s esophagus, chronic esophagitis and esophageal stricture, and paraesophageal hernia, which has been associated with shortening of the esophagus. Many surgeons advocate the Collis modifications of the standard Belsey and Nissen operations to avoid recurrent hiatal hernia when esophageal shortening is suspected pre-operatively or discovered intra-operatively. In our experience, adequate length of intra-abdominal esophagus can virtually always be obtained and maintained without the need for any esophageal lengthening techniques by appropriate extensive mobilization of the esophagus from the abdomen and use of the firmly anchored Hill operation. This issue strongly suggests that the Hill repair has significant advantages over the other repairs, particularly when dealing with short esophagus and paraesophageal hernias.

Barrett’s esophagus, chronic esophagitis and esophageal stricture, and paraesophageal hernia, which has been associated with shortening of the esophagus. Many surgeons advocate the Collis modifications of the standard Belsey and Nissen operations to avoid recurrent hiatal hernia when esophageal shortening is suspected pre-operatively or discovered intra-operatively. In our experience, adequate length of intra-abdominal esophagus can virtually always be obtained and maintained without the need for any esophageal lengthening techniques by appropriate extensive mobilization of the esophagus from the abdomen and use of the firmly anchored Hill operation. This issue strongly suggests that the Hill repair has significant advantages over the other repairs, particularly when dealing with short esophagus and paraesophageal hernias.

We continue to advocate the routine use of intraoperative manometry to control the degree of plication at the level of the GE junction to minimize the incidence of postoperative dysphagia and to eliminate the need for inserting a bougie when constructing the repair. The routine application of intraoperative manometry allows modification of the repair (see Surgical Technique) to obtain

lower esophageal sphincter pressures between 25 and 55 mm Hg. These intraoperative pressures have been shown to translate postoperatively to pressures in the normal range, between 15 and 30 mm Hg.

lower esophageal sphincter pressures between 25 and 55 mm Hg. These intraoperative pressures have been shown to translate postoperatively to pressures in the normal range, between 15 and 30 mm Hg.

Patient Selection

Appropriate patient selection is essential to help ensure good outcomes, including improvement in quality of life. The majority of operative candidates should have typical symptoms that are chronic and refractory to standard medical therapy. With the increasing application of the laparoscopic approach to the treatment of GERD, an ever-increasing temptation is to offer surgical treatment to the patients who are asymptomatic but require regular or high-dose medications. This can be acceptable, especially in young patients who wish to avoid lifetime dependence on medications. If a good outcome is to be achieved in these asymptomatic patients, however, attention to patient selection and operative approach must be particularly meticulous.

All patients being considered for antireflux surgery should undergo preoperative endoscopy and manometry to document the presence of Barrett’s esophagus or significant motility disorder. Our practice continues to utilize 24-hour pH studies in the majority (more than 90%) of patients to confirm the diagnosis by verifying an abnormal level of gastroesophageal reflux and, more important, to demonstrate a high level of correlation between symptoms and reflux episodes.

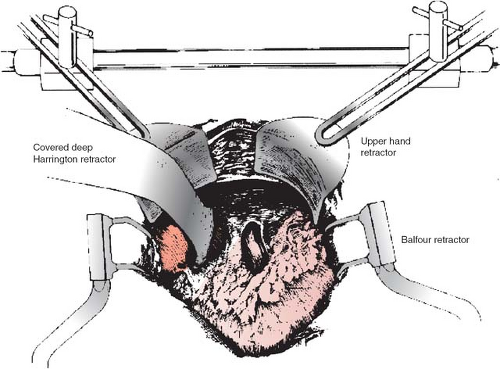

The operation is performed with the use of both general and epidural anesthesia whenever possible. The epidural is continued postoperatively in a patient-controlled mode, which has greatly facilitated early patient mobilization and discharge. The patient is positioned supine with the right arm tucked and left arm abducted at 90 degrees. A limited upper abdominal midline incision is made from the xiphisternum to 4 to 6 cm above the umbilicus, with the xiphoid process excised if necessary. The “upper hand” retractor system (V. Mueller, Allegiance, Deerfield, IL) is used throughout the procedure and utilizes two right-angled retractor blades suspended from a transverse bar positioned 3 to 4 cm above the patient’s chest. The blades of the retractor are placed under the right and left costal margins, which are retracted superiorly and laterally. This retraction results in a verticalization of the diaphragm, which allows the operating team to work straight down on the GE junction rather than struggling under the diaphragm. The lower aspect of the incision is held open with a Balfour retractor (Fig. 4). The left lateral segment of the liver is then mobilized from the diaphragm, with the triangular ligament taken down and the inferior phrenic vein carefully avoided. The gastrohepatic ligament including the hepatic branches of the vagus nerves is incised. This allows retraction of the caudate lobe and the lateral segment of the left lobe of the liver to the right using a deep Harrington retractor (Fig. 4). The dissection then proceeds over the anterior aspect of the esophageal hiatus. Any hiatal hernia is reduced and the peritoneal reflection is incised to identify the anterior surface of the esophagus. Gentle finger dissection along the right and left crux of the diaphragm facilitates delineation of the esophagus, which is manually encircled; the posterior vagus nerve is kept closely applied to the esophagus. This dissection should be easy to perform in a virtually bloodless plane when done correctly. A 1-in Penrose drain is

then passed around the esophagus and both vagus nerves to facilitate retraction through the remainder of the mobilization of the esophagogastric (EG) junction. Dissection proceeds inferiorly along the medial aspect of the right crus to the point where it converges with the left crus. The esophagus is gently retracted anteriorly and to the patient’s left, and the lower aspect of the left crus is mobilized. The peritoneal coverings of the left and right crus should be preserved. The fundus is completely mobilized from the EG junction to the level of the first short gastric vessel. A significant advantage of the Hill operation over the classic Nissen fundoplication is that there is no need to take down the short gastric vessels. If any indication is seen of esophageal shortening at this point, the distal esophagus can be mobilized for a variable distance to facilitate complete reduction of the EG junction into the abdomen. The mobilization can involve up to 10 to 12 cm of distal esophagus when necessary.

then passed around the esophagus and both vagus nerves to facilitate retraction through the remainder of the mobilization of the esophagogastric (EG) junction. Dissection proceeds inferiorly along the medial aspect of the right crus to the point where it converges with the left crus. The esophagus is gently retracted anteriorly and to the patient’s left, and the lower aspect of the left crus is mobilized. The peritoneal coverings of the left and right crus should be preserved. The fundus is completely mobilized from the EG junction to the level of the first short gastric vessel. A significant advantage of the Hill operation over the classic Nissen fundoplication is that there is no need to take down the short gastric vessels. If any indication is seen of esophageal shortening at this point, the distal esophagus can be mobilized for a variable distance to facilitate complete reduction of the EG junction into the abdomen. The mobilization can involve up to 10 to 12 cm of distal esophagus when necessary.

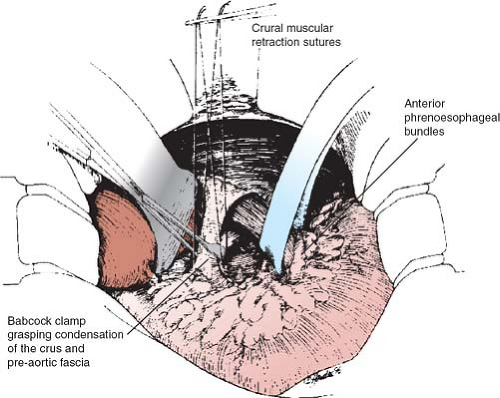

If the esophagus is mobilized as described along its normal anatomic planes, both the anterior and posterior phrenoesophageal bundles will be intact and easily visible at the level of the EG junction. The Hill repair uses these strong tissue bundles to re-create the angle of His and reestablish the esophageal flap valve apparatus while anchoring the repair in the abdomen. The phrenoesophageal bundles are composed of fibrofatty tissue and vary significantly in size and bulk according to the patient’s body habitus. They form the natural attachments of the EG junction to the diaphragm (Fig. 2).

Fig. 4. The retraction apparatus used to provide exposure of the esophageal hiatus. The setup facilitates the “verticalization” of the diaphragm so the surgical team can look straight down to the operative field.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|