Models of International Operations

A method developed on one continent has difficulty being accepted on another.

–Fritz Beller

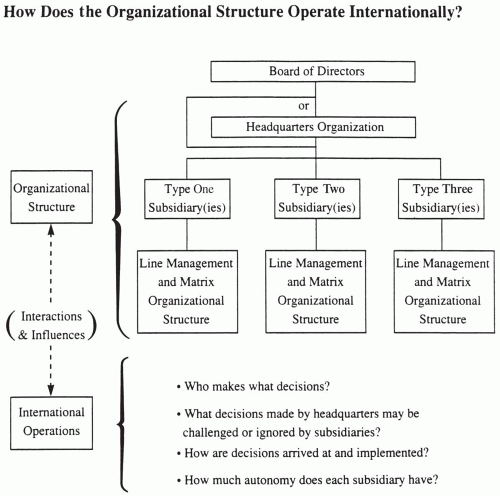

The term international operations is used in this chapter to describe how a multinational pharmaceutical company functions when it has sites in two or more countries that are actively involved in discovering and developing new drugs. Another way of expressing this concept is to examine how the organizational structure actually works. Although this question is important to consider at all levels of a company (e.g., individual scientist, department, large division such as marketing, overall), this chapter focuses particularly on the overall company level. The major distinctions between organizational structure and international operations are shown in Fig. 18.1.

Numerous models exist of how a multinational pharmaceutical company is organized or structured (Chapter 19). The overall organizational structure of a company may or may not reflect the nature of its international operations. A company’s organizational chart describes reporting relationships but does not necessarily indicate how decisions are made. For example, it is important for subsidiary companies to know what degree of input they have into major decisions reached at headquarters that affect them and what type of decisions the subsidiaries may make independent of the parent company. This chapter discusses operations at the overall company level and does not discuss organizational structure in any detail. While it may initially appear that the operations and the styles of an organization are more or less fixed, most organizations operate in a state of flux. Many move in a narrow area around a fixed concept or anchor, while others appear to wander aimlessly from one style or approach to another, and still others move in a predetermined direction toward a goal.

This chapter does not discuss reporting relationships, matrix versus line management concepts, or whether to organize a group by functions and responsibilities or according to the skills and personalities of the senior managers. Those concepts are discussed in Chapter 19 and in Guide to Clinical Trials (Spilker 1991).

This chapter describes the manner and style by which the overall company functions.

This chapter describes the manner and style by which the overall company functions.

TYPES OF SUBSIDIARIES AND DRUG DEVELOPMENT SITES

Before describing five basic models of international pharmaceutical operations, it is important to describe the concept and range of subsidiaries. A headquarters is defined as the place where the multinational company has its major or parent offices. Subsidiaries are defined as those company sites that are wholly, primarily, or partly owned by the parent organization. Only one subsidiary of a single company is said to exist within a single country. If a company owns a manufacturing plant in one city, a research facility in another city within the same country, and a sales office in a third city, all three together are considered a single subsidiary. Joint ventures, comarketing activities, and licensed activities are not specifically described in this chapter.

This particular discussion is limited to human pharmaceutical products (i.e., drugs) to simplify the points to be made, although the descriptions may apply to other products made by pharmaceutical companies (e.g., agricultural products, veterinary products) or to related industries (e.g., medical devices). Three different types of subsidiaries are described based on the scope of their functions.

Type One Subsidiary: A Fully Functional Research and Development Site

The most complete pharmaceutical subsidiary is one that conducts all three basic functions of industrial research and development (i.e., discovers new drugs, develops new drugs, and expands the drugs’ characteristics or product line after initial marketing). This site also markets the company’s drugs and may or may not be involved in their manufacture. It is not necessary that a site at this level be 100% able to conduct every step in the discovery-development-marketing chain, although many multinational pharmaceutical companies have at least one subsidiary that is able to achieve this scope of

activities. This type of subsidiary is referred to as a major subsidiary throughout this chapter.

activities. This type of subsidiary is referred to as a major subsidiary throughout this chapter.

Type Two Subsidiary: A Group that Functions at a Lower Level Overall or Less Broadly Than a Type One Subsidiary

This type of a pharmaceutical subsidiary has somewhat limited functions. The subsidiary may solely conduct discovery research, technical development, or clinical activities, in addition to the critically important function of marketing the company’s products. This subsidiary may even conduct all of these activities but is not considered a Type One subsidiary because of its small size, limited expertise, or limited range of activities. It may be highly specialized in a single therapeutic area. The subsidiary is generally viewed by headquarters as an important subsidiary that contributes in a substantial way to the development of a specific type of drug or in a specific technical area (e.g., the subsidiary represents the core of a certain expertise within the company).

Type Three Subsidiary: A Group that Functions at a Limited or Less Complete Level Than Type One or Two Subsidiaries

The third type of subsidiary primarily markets the company’s products and, in addition, may conduct a clinical trial on an investigational or marketed drug within a single country. The clinical trials conducted by the subsidiary may be proposed by the medical director or staff within the subsidiary or by the headquarters staff. The trial is approved (a) solely by the headquarters, (b) jointly by the headquarters and subsidiary, or (c) solely within the subsidiary. The choice among these approaches is generally, but not necessarily, based on the operational model used by the specific company. This type of subsidiary rarely, if ever, participates in developing the overall clinical plan on a new investigational drug. Many subsidiaries of this type are solely sales organizations and never conduct any clinical trials.

Regulatory affairs personnel within this type of subsidiary may take the headquarters’ dossier on a new drug, add on any nationally conducted clinical trials or studies, and rework the dossier for submission to their national regulatory authorities. On the other hand, the regulatory affairs group within this subsidiary is sometimes instructed to submit the dossier prepared for them by the headquarters staff. In that situation, the local regulatory affairs personnel are still often responsible for interacting with their regulatory agency personnel when questions arise.

Major versus Minor Subsidiaries

The most common distinction made between major (i.e., Type One) and minor (i.e., Type Three) subsidiaries is between those groups conducting research and drug development and those that are not. This distinction may be adequate for some pharmaceutical companies, but for others, greater clarity is desired, particularly for considering Type Two subsidiaries. Type Two subsidiaries are not purely major or minor subsidiaries. Finer distinctions between major and minor subsidiaries for Type Two could include consideration of the following two questions.

Does the subsidiary conduct research directed toward discovery of new drugs? Companies usually limit the number of countries in which significant discovery activities occur. There is currently some controversy whether multinational pharmaceutical companies should seek to centralize this function or divide it into two or more distinct parts. This issue is not discussed in this chapter, although it is clear that there is no consensus on this question and different companies are moving in different directions. Most of the largest corporations have moved to conduct their research and development on two or sometimes more continents.

Does the subsidiary conduct development activities on investigational drugs that are intended to help achieve regulatory authority approval to launch the drug in major territories? This consideration may be used to distinguish between subsidiaries that conduct marketing-oriented studies (on investigational drugs) primarily or solely intended for their own market. These studies are usually included in a regulatory dossier to provide the regulatory authorities of that country with an enhanced “comfort level” that patients within their own country have been treated with a new drug and respond similarly to the drugs as do patients from other countries.

MODELS OF INTERNATIONAL OPERATIONS AND STYLES OF DECISION MAKING

A single spectrum of international pharmaceutical company operations and styles is described, ranging from highly centralized to highly decentralized operations. Five models along that spectrum are illustrated and discussed (see Fig. 18.2).

A centralized international operation with a dictatorial one-way style of decision making that flows from headquarters to all subsidiaries

A centralized international operation with a collaborative style of decision making involving headquarters and the major subsidiary(ies)

A balanced international operation with a style emphasizing equality in decision making between headquarters and the major subsidiary(ies)

A decentralized international operation with a semiautonomous style of decision making for the headquarters and major subsidiary(ies)

A decentralized international operation with an independent style of decision making for the major subsidiary(ies)

Major pharmaceutical companies may be identified that match or approximate each of these five styles, but this information is not presented for several reasons, one being that some of the examples the author was aware of ten to 20 years ago have changed markedly.

Model 1: Centralized International Operations with a Dictatorial Decision-making Style

In many ways, this model is the easiest one for a company to establish and maintain. This model is implemented so that a single site controls all of the major decisions and subsidiaries are provided (hopefully) with clear directions to follow. Assuming that each of the five models has been sensibly established and is being efficiently run, fewer questions or issues generally arise with this model as compared with the others.

The major disadvantage of this model is that the managers of the major subsidiaries are removed from the major decision-making process. This is often demotivating for highly competent

managers, even if all decisions made by the parent organization are correct and appropriate. Any mistakes by the parent group will be magnified because of lack of “buy-in” and shared decision making by the subsidiaries. This should be avoided as much as possible by the parent group that uses this model through informal discussions with subsidiary managers prior to announcing and implementing decisions. Nonetheless, the subsidiary managers recognize their lack of decision-making ability at the highest levels and must be content with their power within limits established by the headquarters.

managers, even if all decisions made by the parent organization are correct and appropriate. Any mistakes by the parent group will be magnified because of lack of “buy-in” and shared decision making by the subsidiaries. This should be avoided as much as possible by the parent group that uses this model through informal discussions with subsidiary managers prior to announcing and implementing decisions. Nonetheless, the subsidiary managers recognize their lack of decision-making ability at the highest levels and must be content with their power within limits established by the headquarters.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree