Minimally Invasive Total Gastrectomy

Elliot Newman

Marcovalerio Melis

DEFINITION

Please refer to the Minimally Invasive Distal Gastrectomy chapter for details on definitions and indications.

Currently, total gastrectomy is indicated for adenocarcinoma of the stomach where the proximal location precludes a lesser resection with a proximal 5- to 6-cm grossly negative margin.

Randomized trials have shown that total gastrectomy offers no oncologic value over a distal gastrectomy as long as a negative margin can be obtained.1,2

Occasionally, gastrointestinal stromal tumors located near the gastroesophageal junction may also require a total gastrectomy to achieve negative resection margins.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Following the diagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma, accurate clinical staging is necessary.

Endoscopic ultrasound will evaluate depth of tumor invasion and possible lymph node metastases

Computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest abdomen and pelvis will evaluate for metastatic disease.

Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT is recommended if no metastatic disease is detected by the CT.

Diagnostic laparoscopy can be considered for advanced tumors (e.g., T3N1) to rule out subradiographic peritoneal dissemination.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

Same as Minimally Invasive Distal Gastrectomy. Please refer to the appropriate chapter.

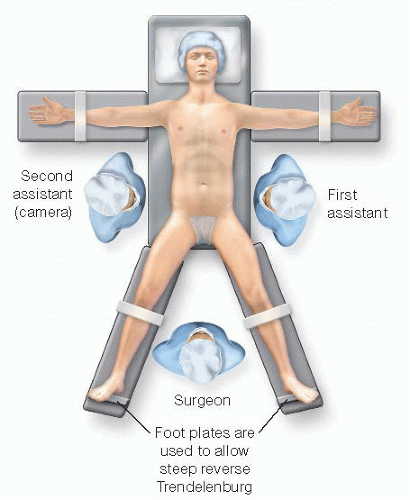

Positioning

Same as Minimally Invasive Distal Gastrectomy (FIG 1)

Please refer to the appropriate chapter for further details.

TECHNIQUES

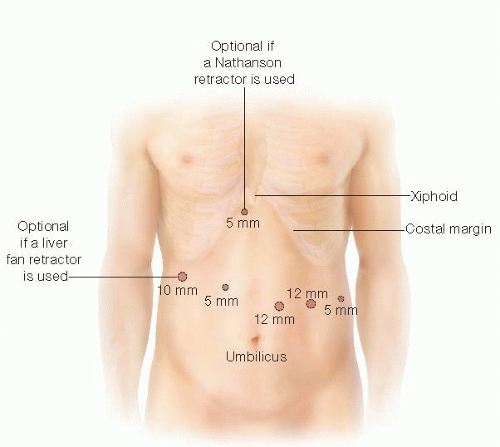

ACCESS AND PORT PLACEMENT

Same as Minimally Invasive Distal Gastrectomy, except for the camera port, which is placed routinely two to three fingerbreadths above the umbilicus and to the left of the midline, and a 15-mm trocar used for the most lateral trocar site on the left (FIG 2).

Please refer to the appropriate chapter for further details.

DISSECTION OF THE GREATER CURVE

Retract the transverse colon and the greater omentum caudally.

Access the lesser sac by entering the gastrocolic ligament in an avascular area with ultrasonic shears.

Extend the dissection of the gastrocolic ligament distally toward the pylorus and cephalad toward the spleen with the ultrasonic shears.

Continue the dissection of the gastrocolic ligament along the upper third of the greater curvature with the division of the left gastroepiploic vessels and then the gastrosplenic ligament including the short gastric vessels. This portion of the dissection is greatly facilitated by bringing the stomach down and rolling it up to expose the back wall of the stomach.

By performing the dissection of the greater curvature lateral to the gastroepiploic arcade, the lymph nodes along the gastroepiploic vessels (stations 4d and 4sb) are included in the specimen.

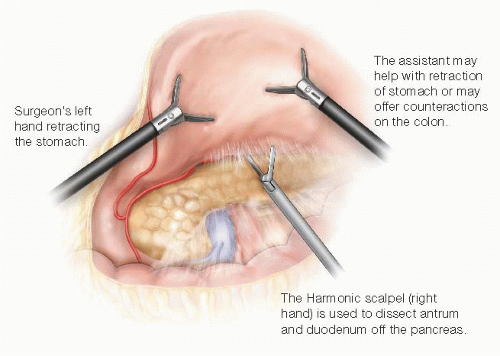

In order to expose the lesser cavity in its entirety, divide the avascular posterior gastropancreatic adhesions that are almost always present between the posterior wall of the stomach and the anterior surface of the pancreas. Division of those adhesions will also facilitate anterior retraction of the stomach (FIG 3).

FIG 3 • The stomach is retracted anteriorly to the patient’s right, and adhesions between pancreas and posterior aspect of the stomach are divided.

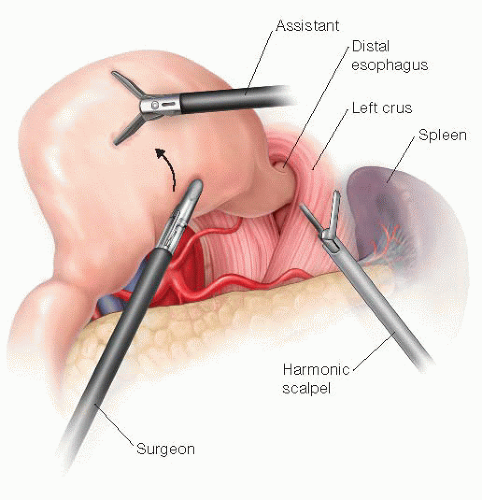

Next, continue the dissection more cranially along the greater gastric curvature, until all of the short gastric vessels are divided and the fundus is completely mobilized. At this time, the left crus and the hiatus with the distal esophagus should be visualized (FIG 4). Having the operating surgeon retract the anterior fundus toward the anterior abdominal wall and to the patient’s right with the assistant retracting the posterior fundus in the same direction can improve the exposure.

Using the ultrasonic dissector, divide the lateral portion of the phrenoesophageal ligament and expose the fibers of the left crus.

FIG 4 • The greater curvature is completely dissected off the spleen and the stomach is elevated and rotated to the right, exposing the diaphragmatic hiatus. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree