Minimally Invasive Esophagectomy

Benjamin We

Robert J. Cerfolio

Mary T. Hawn

DEFINITION

The incidence of esophageal cancer, especially adenocarcinoma, has increased dramatically over the past decades. This phenomenon is secondary to the increasing incidence of obesity contributing to rising rates of reflux and Barrett’s esophagus in the United States.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients with esophageal malignancy present with progressive dysphagia and weight loss. The incidence is higher in men and in smokers. Patients often have a long-standing history of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. The physical examination is usually unremarkable.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

All patients with dysphagia should be evaluated with an upper endoscopy and biopsy of suspicious lesions. Patients with biopsy-proven carcinoma are staged to determine treatment. The staging process includes computed tomography (CT) of the chest and abdomen, an integrated positron emission tomography (PET)/CT, and endoscopic ultrasound. Patients with T3 or N1 disease are treated with neoadjuvant chemoradiation and restaged prior to resection.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

If the patient is unable to maintain adequate nourishment during neoadjuvant therapy or is malnourished and too weak for resection, we place a jejunostomy tube (J-tube), preferably with a laparoscopic approach. This allows for staging and the ability to rule out metastatic disease. A percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube should be avoided in any patient that is being considered for esophageal resection. Additionally, having the J-tube placed up front minimizes the abdominal portion of the esophageal resection procedure.

Positioning for the Abdominal Portion

The patient is positioned in the supine position with both arms tucked and a Foley catheter in place. We do not routinely use an arterial line or a central line. A nasogastric tube (NGT) is routinely placed. If one is placed, care must be taken to pull it far back into the esophagus as well as to remove all esophageal temperature probes or other devices prior to stapling the stomach. If body habitus or other concerns prevent arm tucking, it is not a necessity.

TECHNIQUES

PORT PLACEMENT

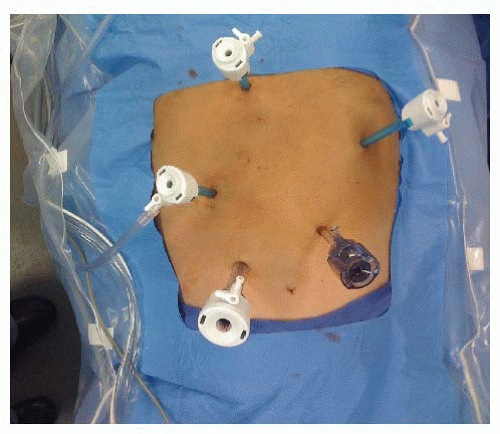

A Veress needle entry technique is used to place a 5-mm trocar approximately 15 cm inferior to the xiphoid and 3 cm to the left of the midline. The abdomen is then inspected for evidence of distant disease and any suspicious areas are biopsied and sent for frozen section. Four additional trocars are placed: (1) 12-mm trocar is placed 7 cm inferior to the right costal margin and 3 cm from the midline, (2) 5-mm trocar is placed 6 cm superior to the 12-mm trocar and usually to the right of the falciform ligament, (3) 5-mm trocar just off midline to the right and inferior to the base of the xiphoid to retract the left lateral segment of the liver. A 5-mm locking grasper positioned underneath the left lateral segment of the liver and the diaphragm is grasped anterior and to the right of the esophageal hiatus taking care to avoid the phrenic vein, and (4) 5-mm trocar 2 cm below the left costal margin in the anterior axillary line (FIG 1).

The patient is positioned in moderate reverse Trendelenburg position. The surgeon stands on the patient’s right side and uses the two right-sided ports. The assistant stands on the patient’s left and uses the left subcostal port and camera port.

CRURAL DISSECTION AND ESOPHAGEAL MOBILIZATION

The gastrohepatic ligament is divided using an ultrasonic dissector. The right crus of the diaphragm can then be identified at the esophageal hiatus. The phrenoesophageal ligament is divided anteriorly, taking care to follow the stomach toward the angle of His, lateral and inferior to the left esophageal crus. The crura are dissected circumferentially and the esophagus is isolated.

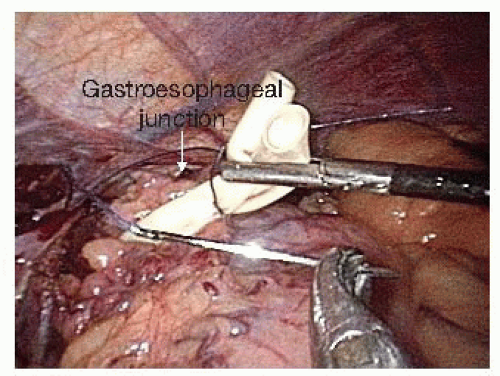

Once the retroesophageal window is completed, a Penrose drain is placed around the gastroesophageal junction. The two tails are sutured together with a single 2-0 Vicryl stitch to use as a handle to assist in the crural dissection and for intrathoracic pull-up and manipulation during the second portion of the procedure (FIG 2). Dissection of the lower 5 to 7 cm of the esophagus is then performed while the assistant places the Penrose on traction. This can mostly be performed with blunt dissection. If the left pleural space is entered, we place a chest tube at the completion of the abdominal portion of the operation. Radiation changes can make this part of the dissection more difficult.

GREATER CURVATURE DISSECTION

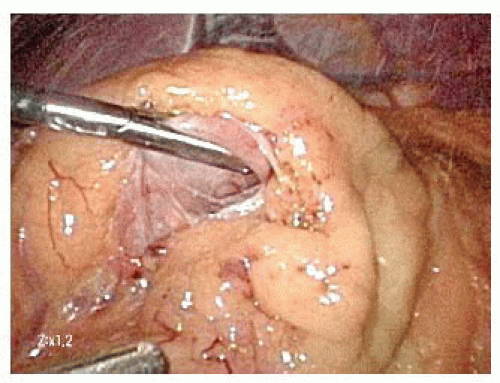

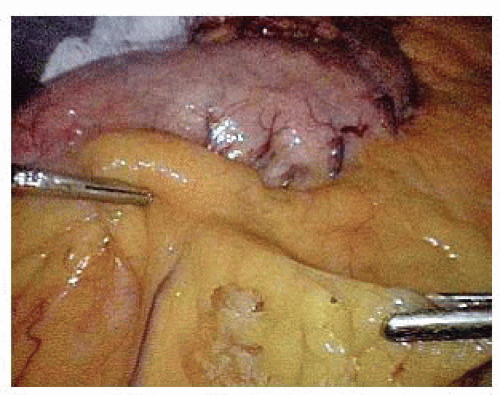

On the distal aspect of the greater curvature of the stomach approximately 5 cm proximal to the pylorus, the greater curvature is grasped and elevated anteriorly by the surgeon’s left hand and the assistant places the transverse colon on downward traction. The surgeon divides the gastrocolic ligament well inferior to the projected course of the right gastroepiploic vessels. Because the right gastroepiploic vessels will serve as the primary blood supply for the gastric conduit, great care is taken to avoid injuring these vessels during greater curvature dissection (FIG 3).

The lesser sac is entered at least 1 to 2 cm inferior to the right gastroepiploic vessels projected course. Once the lesser sac is entered, the posterior stomach wall is grasped and elevated anteriorly and to the patient’s right side with the surgeon’s left hand to open the dissection tension plane. This maneuver positions the gastroepiploic vessels anteriorly and helps protect them from injury due to inadvertent grasping (FIG 4).

Dissection is then carried proximally, taking care to stay superior to the transverse colon as it courses toward the splenic flexure. This is accomplished by lifting the posterior stomach wall anteriorly and toward the patient’s right side with the surgeon’s left hand while the assistant retracts the greater omentum inferiorly and to the patient’s left. The proximal aspect of the greater curvature is mobilized by dividing all short gastric vessels until the left crus of the diaphragm is reached. If there is excess omentum impeding the view, we will place a “fat stay” using a 2-0 Vicryl suture on an MH needle. The suture is placed through the fat, the needle is removed, and the assistant grasps both ends of the suture and extracts them through the left-sided trocar. The trocar is then removed and reinserted so that the suture comes through the track but not the trocar. Tension is placed on the suture until the fat is retracted; then, the suture is secured with a hemostat at the level of the skin.

We leave some omentum along the superior aspect of the greater curvature of the stomach to be used to buttress the intrathoracic anastomosis.

FIG 3 • Identification of the right gastroepiploic vessels adjacent to the greater curvature and entering the lesser sac. |

LESSER SAC AND LEFT GASTRIC PEDICLE DISSECTION

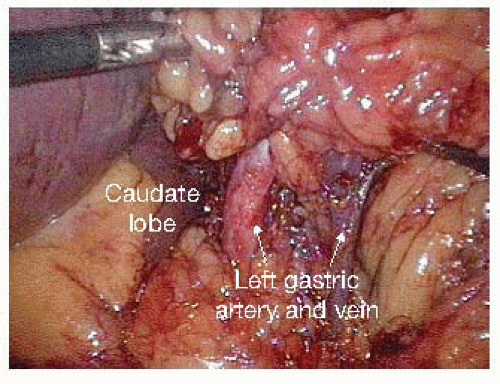

The posterior attachments to the stomach are divided, exposing the origin of the left gastric vessels along the lesser curvature. In exposing the left gastric artery, the adjacent fat and lymph nodes should be elevated anteriorly to allow for resection with the specimen.

The left gastric vessels are then identified on the medial aspect of the lesser curvature. Once these vessels are skeletonized, a white vascular (2.5 mm) staple load is fired across the left gastric artery at its origin from the celiac axis (FIG 5).

THE PYLORUS

The gastrocolic ligament is divided beyond the pylorus with care of staying away from the origin of the right gastroepiploic vessels.

A Kocher maneuver is performed to further mobilize the pylorus. One good assessment of mobility of the stomach is whether the pylorus can be placed adjacent to the right crus.

We do not perform a pyloromyotomy or pyloroplasty and instead inject botulinum toxin into the anterior wall of the pylorus.

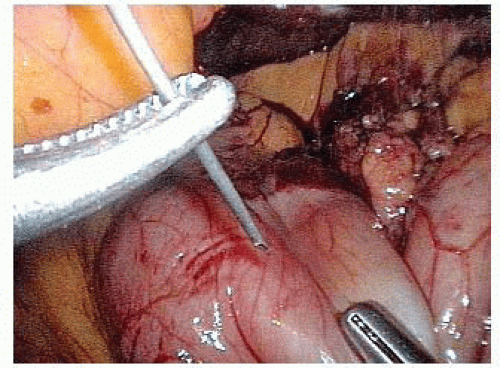

Botulinum toxin (100 units) is diluted into 5 mL of saline and drawn into a syringe. A 20-gauge spinal needle is inserted into the anterior aspect of the pylorus (FIG 6). The total volume of botulinum toxin is divided into at least three to four separate injection sites along the anterior pylorus.

CREATION OF THE GASTRIC CONDUIT

The lesser curvature is cleared of omentum at approximately the level of the incisura to allow for an avascular landing zone for the first staple load on the stomach (FIG 7).

The conduit is created with sequential applications of a 60-mm stapler using green (4.8 mm) loads aiming toward the angle of His. The goal is to create a conduit that is 6 to 8 cm in width. Once divided, staple-line integrity and hemostasis are verified.

The conduit is then sutured to the proximal stomach remnant using two interrupted 2-0 Vicryl stitches of alternate color to facilitate orientation following the thoracic pull-up (FIG 8). The tails are left at least 5 cm long to assist in intrathoracic location/manipulation and the first stitch is always placed at the superior apex of the conduit to diminish pull-up tension.

The surgeon then places the Penrose drain and proximal stomach into the posterior mediastinum. We do not routinely enlarge the hiatus unless there appears to be constriction of the conduit.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree