Minimally Invasive Distal Gastrectomy

John K. Saunders

Marcovalerio Melis

DEFINITION

The indications for minimally invasive distal gastrectomy (MIDG) do not differ from the indications for open gastrectomy and include both benign and malignant diseases.

Gastric malignancies (adenocarcinomas, neuroendocrine tumors, gastrointestinal stromal tumors [GIST], and other submucosal neoplasms) account for the single largest indication for gastric resection and will be the focus of this chapter.

MIDG performed for malignancies should follow the same standard oncologic principles generally followed during open resections.

For adenocarcinomas, gastric resection should be extended proximally for 5 to 6 cm from the gross tumor margins. For tumors of the distal stomach, this is generally achievable with a partial gastrectomy. Randomized trials have shown that total gastrectomy offers no oncologic value over a distal gastrectomy as long as a negative margin can be obtained.1,2 Appropriate extent of lymphadenectomy for gastric adenocarcinoma in the western population is a topic of great debate and beyond the scope of the present chapter. In our practice, we usually perform a D2 lymph node dissection. A recent meta-analysis has shown that MIDG for gastric adenocarcinoma is safe and associated with reduced overall morbidity.3 Comparative studies with long-term follow-up are still lacking, but available evidence suggests that oncologic outcomes are comparable after either MIDG or open distal gastrectomy. Perioperative chemotherapy is indicated for any gastric adenocarcinoma stage T2N0M0 or greater as recommended by National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines.

For GIST, gastric resection follows different oncologic principles. A lymph node dissection is not required and surgery is considered curative as long as the resection margins are negative. Therefore, more limited resections (e.g., wedge resections) are appropriate for GIST. Partial gastrectomies may still be required for large tumors or when the gastroesophageal junction or the pylorus is involved.

Although decreasing in frequency, complications of peptic ulcer disease (bleeding, gastric outlet obstruction, failure of medical treatment) are still significant indications for distal gastrectomy. The same technique described in this chapter may be used for benign pathologies, omitting the lymphadenectomy.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Following the diagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma, accurate clinical staging is necessary.

Endoscopic ultrasound will evaluate depth of tumor invasion and possible lymph node metastases.

Computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest abdomen and pelvis will assess metastatic disease.

Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT is recommended if no metastatic disease is detected by the CT.

Diagnostic laparoscopy can be considered for advanced tumors (e.g., T3N1) to rule out subradiographic peritoneal dissemination but not routinely indicated.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

The choice of laparoscopic versus open techniques should be at the discretion of the surgeon.

Regardless of the technique, the primary goals of the operation are the same: resection of the cancer with negative margins and restoration of intestinal continuity.

The patient should be medically optimized for surgery. Special attention needs to be given to malnourished patients.

Preoperative nutritional panels are mandatory, and occasionally, the placement of a preoperative feeding jejunostomy is warranted. Consider preoperative tube feedings in patients with significant weight loss or other evidence of malnutrition, especially if candidates for neoadjuvant treatment.

Consider neoadjuvant treatment for lesions T2 or greater and/or for suspected lymph node involvement.

Insist on smoking cessation to reduce postoperative pulmonary and wound complications.

Consider a preoperative liquid protein diet to improve steatohepatitis in obese patients.

Perioperative antibiotic should be given within 30 minutes prior to the initial skin incision.

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis with calf length pneumatic compression devices or subcutaneous heparin (or both) should be instituted prior to induction of anesthesia.

General anesthesia may be supplemented with epidural analgesia.

The bladder is decompressed with a Foley catheter.

An orogastric or a nasogastric tube is inserted.

Positioning

Use an operating room (OR) table that may accommodate very steep reverse Trendelenburg position.

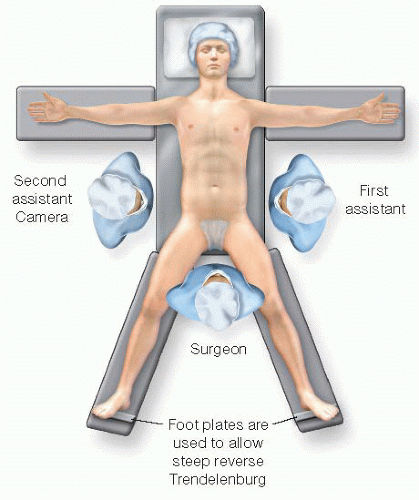

Preferred position is supine split leg with foot plate attachments to prevent patient migration. The foot plates should be snugly placed with the toes pointing slightly outward (FIG 1).

Pad pressure points along arms and legs and secure the knees in the locked position. Pillow cases or folded sheets and 2-in silk tape can be used to keep the knees from buckling. Arms are secured either by Kerlix™ gauze wrapped around the armboard or by commercially made arm straps.

Prior to prepping and draping, check the positioning by manipulating the bed in all of the positions that will be used during the operation.

TECHNIQUES

ACCESS AND PORT PLACEMENT

Port placement is dictated by the body habitus of the patient. The umbilical trocar is generally used for the camera. In obese patients, or with an unusually low umbilicus, the camera port may need to be more cephalad, often two or three fingerbreadths above the umbilicus and left to the midline.

Place a 10-mm trocar at the umbilicus with usual Hassan technique.

Establish a 15 mmHg pneumoperitoneum and perform a diagnostic laparoscopy to rule out peritoneal or hepatic metastases. If metastatic lesions are suspected, they should be biopsied and sent for frozen section prior to committing to gastrectomy. If ascites is present, washings should be performed.

Identify the neoplasm by visualization or by palpation. If unsuccessful, intraoperative endoscopy is encouraged.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree