15 Methods of Primary Prevention

Health Promotion

The most fundamental sources of health are food, the environment, and behavior. Whereas public health managers are concerned with the availability of healthy food and the safety of the environment for the population (see Section 4), this chapter and Chapter 16 explore how preventive medicine clinicians can intervene with individual patients for better health. Here we discuss primary prevention of disease through general health promotion and specific protection. General health promotion by preventive medicine practitioners requires effective counseling driven by theories of behavior change. Chapters 16 and 17 discuss secondary and tertiary prevention for the general population. Chapters 18 to 23 discuss clinical prevention specific diseases for particular populations.

I Society’s Contribution to Health

In addition to the sometimes profound effects of genetics, the most fundamental sources of health do not come from access to the health care system, but rather from the following1,2:

The health care system is of vital importance when it comes to treating disease (and injury), but all of society, and personal actions, provide the basic structure for these three sources of health. Examples for societal sources of health include socioeconomic conditions, opportunities for safe employment, environmental systems (e.g., water supply, sewage disposal), and the regulation of the environment, commerce, and public safety. Society also helps to sustain social support systems (e.g., families, neighborhoods) that are fundamental to health and facilitate healthful behaviors.3

Even in reasonably ordered societies, income must be sufficient to allow for adequate nutrition and a safe environment for individuals and families. Education enhances employment opportunities and helps people understand the forces that promote good health. Coordinated systems of resource distribution are needed to avoid disparities and deprivation that compromise health. A landmark study among British civil servants showed that lower socioeconomic status correlates with poorer health, regardless of the country studied.4 This trend applies not only to direct measures of health or lack of health (e.g., death rates), but also to nutrition, health behaviors, fertility, and mental health.5 Debate continues about what factors to consider in defining socioeconomic groups. In the 1990s, using educational background as a measure of socioeconomic status, investigators showed that disparities between socioeconomic groups in the United States persisted.6 Currently, U.S. statistics are stratified by educational attainment and sometimes by income level or poverty status, but not by a comprehensive measure of socioeconomic status. It is becoming increasingly clear that unhealthy lifestyles and access to medical care explain only some of the socioeconomic differences observed in the United Kingdom and the United States.7

Once people have access to adequate nutrition, clean water, and a safe environment, behavior becomes the major determining factor for health (see Chapters 20 and 21). Genetic makeup and behavior also interact; people’s genes may increase their risk of developing certain diseases. However, it is their behavior that can hasten, prevent, or delay the onset of such diseases.

II General Health Promotion

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines health promotion as “the process of enabling people to increase control over their health and its determinants, and thereby improve their health.”8 It is customary to distinguish general health promotion from specific health protection. General health promotion addresses the underpinnings of general health, especially the following six suggested health behaviors9:

Monitoring and limiting dietary fat intake.

Monitoring and limiting dietary fat intake.

Consuming at least 5 servings of fruits and vegetables per day.

Consuming at least 5 servings of fruits and vegetables per day.

Performing regular physical activity and exercise.

Performing regular physical activity and exercise.

Adhering to medication regimen.

Adhering to medication regimen.

III Behavioral Factors in Health Promotion

Human behavior is fundamental to health. The actual, primary causes of death in the United States and most other countries involve modifiable lifestyle behaviors: cigarette smoking, poor diet, and lack of exercise.2 Therefore, efforts to change patients’ behavior can have a powerful impact on their short-term and long-term health. Clinicians may not be aware of individual behavioral choices made by their patients, and if they are aware, they may not feel comfortable in trying to influence patient choices. Clinicians may also be more likely to counsel patients regarding topics with clear scientific support, such as nutrition and exercise, or that require medical techniques, such as screening or family planning. They are more likely to counsel patients when they discover definite risk factors for disease, such as obesity, hypertension, elevated cholesterol levels, or unprotected sexual activity.

Boxes 15-1 and 15-2 provide specific recommendations for promoting a healthy diet and for smoking cessation. The most recent U.S. Preventive Services Task Force report offers recommendations for clinician counseling on a variety of additional topics, including motor vehicle, household, and recreational injury prevention; youth violence; sexually transmitted diseases; unintended pregnancy; gynecologic cancer; low back pain; and dental/periodontal disease.10

Box 15-1 Health-Promoting Dietary Guidelines

With regard to macronutrient distribution, the Institute of Medicine guidelines call for 20% to 35% of total calories from total fat, 45% to 65% from carbohydrates, and 10% to 35% from proteins. The guidelines further emphasize the restriction of saturated and trans fat and their replacement with monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fat. Processed foods should be eaten sparingly. Alcohol consumption should be modest, with ethanol levels not exceeding 15 g/day for women or 30 g/day for men (one drink for women or two drinks for men).*

http://www.iom.edu/About-IOM/Leadership-Staff/Boards/Food-and-Nutrition-Board.aspx

http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/Publications/DietaryGuidelines/2010/PolicyDoc/ExecSumm.pdf

http://fnic.nal.usda.gov/nal_display/index.php?info_center=4&tax_level=3&tax_subject=256&topic_id=1342&level3_id=5140

From Otten JJ, Hellwig JP, Meyers LD, editors: Dietary reference intakes: the essential guide to nutrient requirements, Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, Washington, DC, 2006, National Academies Press.

Box 15-2 The Five “A”s Model for Facilitating Smoking Cessation, with Implementation Suggestions*

1. Ask about tobacco use during every office visit.

2. Advise all smokers to quit.

3. Assess the patient’s willingness to quit.

4. Assist the patient in his or her attempt to quit.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bv.fcgi?rid=hstat2.section.7741, cited from http://www.aafp.org/afp/2006/0715/p262.html#afp20060715p262-b2.

Modified from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and American Lung Association recommendations.

A Theories of Behavior Change

In order to impact behavior, it is helpful to understand how health behavior is shaped and how people change. Behavior change is always difficult. The advantage of intervening in accordance with a valid theory of behavior change is that the intervention has a higher chance of success. Most health behavior models have been adapted from the social and behavioral sciences. Theories also help in targeting interventions, choosing appropriate techniques, and selecting appropriate outcomes to measure.11 We can only sketch out the basics of the most common health theories here. For further details, readers should consult monographs on the topic.11 Other theories support the approach to changing group norms and helping communities identify and address health problems (see Chapter 25).

Knowledge is necessary, but not sufficient, for behavior change.

Knowledge is necessary, but not sufficient, for behavior change.

Behavior is affected by what people know and how they think.

Behavior is affected by what people know and how they think.

Behavior is influenced by people’s perception of a behavior and its risks, their own motivation and skills, and the social environment.

Behavior is influenced by people’s perception of a behavior and its risks, their own motivation and skills, and the social environment.

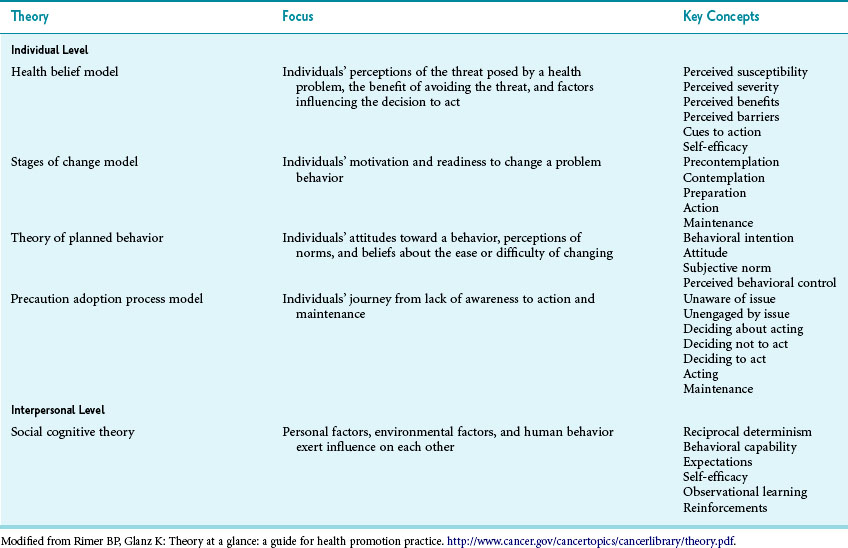

The most common theories for health behavior counseling are the health belief model, transtheoretical model (stages of change), theory of planned behavior, and precaution adoption process model (Table 15-1).

1 Health Belief Model

The health belief model holds that, before seeking preventive measures, people generally must believe the following12:

The disease at issue is serious, if acquired.

The disease at issue is serious, if acquired.

They or their children are personally at risk for the disease.

They or their children are personally at risk for the disease.

The preventive measure is effective in preventing the disease.

The preventive measure is effective in preventing the disease.

There are no serious risks or barriers involved in obtaining the preventive measure.

There are no serious risks or barriers involved in obtaining the preventive measure.

5 Social Learning Theory and Social Cognitive Theory

Behavior and behavior change do not occur in a vacuum. For most people, their social environment is a strong influence to change or maintain behaviors. Social learning theory asserts that people learn not only from their own experiences but also from observing others. Social cognitive theory builds on this concept and describes reciprocal determinism; the person, the behavior, and the environment all influence each other. Therefore, recruiting credible role models who perform the intended behavior may be a powerful influence. This theory has been successfully used to influence condom use.13

B Behavioral Counseling

Many clinicians are uncomfortable with risk factor counseling, thinking they lack counseling skills or time. However, good data show that even brief interventions can have a profound impact on patients. Each year, millions of smokers quit smoking because they want to, because they are concerned about their health, and because their providers tell them to quit. At the same time, even more individuals begin smoking worldwide. Box 15-2 summarizes the approach that the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the American Lung Association recommend for use by clinicians in counseling their patients. Many online training programs are available to assist clinicians in counseling.14

Across a broad area of behavior, patient adherence is based on a functioning physician-patient relationship and skilled physician communication.15 Beyond a good relationship, it matters how clinicians counsel. Despite its venerable tradition, simply giving advice is rarely effective.16 Given the importance of social determinants of health, physician counseling is only one, often minor influence. Even though insufficient to cause change, however, counseling can provide motivation and support behavior change.

1 Motivational Interviewing

Motivational interviewing is a counseling technique aimed at increasing patients’ motivation and readiness to change. It has been shown to be effective across a broad range of addictive and other health behaviors17 and outperforms traditional advice giving.16 Motivational interviewing fits well with the transtheoretical model of change and provides concrete strategies on how to increase people’s motivation toward change. The model rests on three main concepts, as follows:

1. Patients with problem behaviors are ambivalent about their behavior.

2. “I learn what I believe as I hear myself talk.” If the clinician presents one side of the argument and argues for change, it causes the patient to take up the opposite position. It is important to let the patient explore the advantages of changing, and allow the patient to do most of the talking.18

3. Change is motivated by a perceived disconnect between present behavior and important personal goals and values (cognitive dissonance).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree