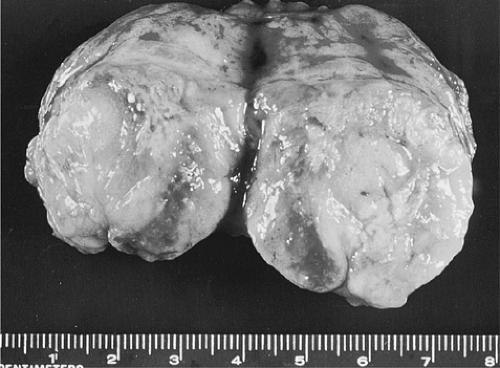

Metastatic Melanoma

Definition

Lymph node metastases of melanoma.

Epidemiology

The incidence of melanoma is increasing rapidly among Caucasians in America, Europe, and Australia. In the US, melanoma is increasing at a rate that exceeds all other neoplasms except for lung cancer in women (1). The skin pigmentation is protective and incidence rates are considerably lower in African-American, Hispanics, and Asians (1). In 2001, the estimates in the US were for 51,800 new cases and 7800 deaths (1). Melanoma is rare in children, median age at diagnosis is 53 years (1).

Pathogenesis

Sunlight, immunological conditions, and genetic abnormalities are the major factors in the origin of melanomas (2). As they evolve, after variable amounts of time, some malignant tumors acquire the ability to disseminate and form new tumors at distant sites. Clark (3), who has studied melanocytic neoplasia extensively, have offered concepts of tumor progression derived from this system that may be applicable to all malignant neoplasia. Melanocytic lesions are pigmented and superficial, and therefore readily apparent and easy to follow. According to his concepts, melanomas arise by generic steps of tumor progression, from melanocytic hyperplasia in the acquired nevus, to aberrant differentiation marked by abnormal hyperplasia and nuclear atypia in the dysplastic nevus, to a primary malignant neoplasm that lacks the ability to metastasize in the radial growth phase, and eventually to a malignant neoplasm endowed with the capacity to metastasize in the vertical growth phase. Morphologically, this crucial transformation occurs when radial growth changes to vertical growth. Thus, for a primary neoplasm to become metastatic, a critical and qualitative change must take place, in which a new population of cells with new properties originates within the neoplasm (3). In most instances, the melanocytes of an acquired nevus follow a pathway of differentiation that leads to their disappearance (3). The transformation from non-neoplastic to neoplastic, from noninvasive to invasive, and eventually from nonmetastatic to metastatic occurs in the melanoma system, as in most other cancers, by processes of mutation and clonal selection.

In the skin, each melanocyte contacts through dendritic processes about 20 to 30 keratinocytes (2). As in other cancers progression to invasion is characterized by changes in cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesion and communication. A main feature in this process is the loss of E-cadherin expression and increase in N-cadherin which coincides with the escape of melanocytes from keratinocyte control and further progress to invasion and metastasis (4).

The studies of Breslow have shown that when the thickness of a cutaneous melanoma exceeds 0.76 mm, the risk for the development of metastases increases in proportion to tumor thickness (5). In Breslow’s series of 138 patients, 39% had primary lesions with a thickness of less than 0.76 mm, and all survived free of disease for 5 years or more, whereas metastases developed in 33% to 84% of those with lesions thicker than 0.76 mm.

The prognostic criteria based on these observations have been confirmed repeatedly. In a large study of prognostic factors in cutaneous melanoma, 90% of patients with superficially invasive, thin primary tumors were alive without recurrence 5 years after surgical excision of the skin lesion (6). In a minority of patients, metastases develop in the regional lymph nodes and, when they do, their chances of survival drop to only 40% at 5 years after lymphadenectomy. In almost all cases, when a cutaneous melanoma reaches the phase of dissemination, it spreads to the regional lymph nodes before it spreads to more distant sites (9,10). Therefore, the progression from stage I to stage II is a very important step in the evaluation of melanoma that must be documented by careful investigation of the regional lymph nodes. A study of 2,227 lymph nodes from 100 patients with clinical stage I cutaneous melanoma revealed no metastases on sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin, yet melanoma cells were detected in 16 nodes from 14 patients when immunostaining with antibody to S100 protein was used (8). A possible pitfall in applying this technique to identify metastatic melanoma cells is that they can be confused with nodal interdigitating reticulum cells, which also express S100 protein (8,11).

Sentinel Lymph Nodes

The status of regional lymph nodes, whether free of tumor or involved by tumor metastasis, is the most important prognostic factor in melanoma, as in many other solid tumors (6). Regional lymphadenectomy provides important staging information and, because tumor metastases are removed, may improve survival. However, it is associated with some morbidity and, as presently practiced, provides only an approximate evaluation of the extent of a tumor. When one or two sections of the central part of a lymph node are obtained and stained with hematoxylin and eosin, according to the standard procedure, only 1% to 5% of the lymph node tissue is examined, so that underestimation can be substantial (12). In studies of breast cancer performed as early as 1948, metastases were demonstrated in 10% to 20% of axillary lymph nodes apparently free of tumor on standard methods of examination when they were processed by serial sectioning (13,14). However, serial sectioning of all regional lymph nodes is too laborious and expensive to be adopted as a routine procedure. The technique of sentinel lymph node biopsy was developed as a minimally invasive method that is associated with low morbidity and is capable of identifying micrometastases (15). In a study of 235 sentinel lymph nodes obtained from 94 patients with primary cutaneous melanoma, 2,700 sections were cut, immunostained with antibodies against melanocytes, and examined (16). In this way, melanoma micrometastases were identified in 12% of patients whose lymph nodes had appeared tumor-free when processed by the routine procedure. In the commonly used sentinel lymph node biopsy procedure, sulfur colloid labeled with

technetium 99 m is injected 3 hours before surgery into the dermis around the primary melanoma or the biopsy scar (13). In addition to or instead of the radioactive substance, a blue dye, isosulfan blue (Lymphazurin), can be injected. The radioactive sentinel lymph nodes are located with a hand-held γ detector and/or by following the blue-colored lymphatics during the operation, which is performed 1 to 3 hours later. In the study in which a 12% increase in the number of positive lymph nodes was noted, three serial tissue sections, each with a thickness of 4 μm and at levels 80 μm apart, were obtained and immunostained with S100, HMB-45, and MART-1 antibodies (16). All the additional lymph node metastases were microscopic and located in the subcapsular sinuses.

technetium 99 m is injected 3 hours before surgery into the dermis around the primary melanoma or the biopsy scar (13). In addition to or instead of the radioactive substance, a blue dye, isosulfan blue (Lymphazurin), can be injected. The radioactive sentinel lymph nodes are located with a hand-held γ detector and/or by following the blue-colored lymphatics during the operation, which is performed 1 to 3 hours later. In the study in which a 12% increase in the number of positive lymph nodes was noted, three serial tissue sections, each with a thickness of 4 μm and at levels 80 μm apart, were obtained and immunostained with S100, HMB-45, and MART-1 antibodies (16). All the additional lymph node metastases were microscopic and located in the subcapsular sinuses.

The number of sentinel lymph nodes can be minimized without influencing the reliability of staging was shown by a study of the lymph nodes involved by metastasis (17). Only nodes with the hottest radioactivity and those with more than 70% of that value as recorded with the hand-held gammaprobe were examined resulting in 1.3 sentinel lymph nodes dissected per patient. The results were 22% positive lymph nodes which was 100% successful in identifying the metastses and decreasing the cost of the procedure (18).

In the largest trial of sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma conducted to date, 1,269 patients with an intermediate thickness melanoma were randomly assigned to sentinel node biopsy followed, if positive, by immediate lymphadenectomy or to observation until palpable lymph nodes were detected (18). The 5-year survival was substantially greater in the first group. Consequentially, the concept of the sentinel lymph node biopsy in melanoma was endorsed by most oncologic societies and is now a well established procedure.

Frozen sections in sentinel lymph nodes are discouraged because trimming the specimens wastes valuable tissues that may be the only ones containing metastases. The use of frozen sections in the analysis of sentinel lymph nodes in patients with melanoma was investigated in a study of 58 patients (19). Although no false-positive diagnoses were obtained with frozen sections, the rate of false-negatives was 38%, too high to be useful. This high rate was a consequence of the inability to detect on frozen sections small metastases that became apparent on permanent section and immunohistochemistry. It is concluded from this and other observations that, given the important therapeutic consequences of the sentinel lymph node diagnosis, frozen section should no longer be part of the procedure, which therefore must be performed in two separate steps (19).

Clinical Syndrome

Patients with stage II melanoma present with a painless mass that in one study ranged in size from 1 to 18 cm in diameter (median, 4 cm) (20) (Fig. 87.1). A particular aspect of melanomas that causes major difficulties in diagnosis and prognosis is occasional spontaneous regression. This phenomenon, probably related to complex interrelations with tissue immunity, is more common in melanomas than in any other malignant tumor. As a result, some cutaneous melanomas with a thickness of less than 0.76 mm are associated with lymph node metastases (21). Even more difficult to interpret are metastatic melanomas with occult primary tumors, estimated to represent about 4% of cases (22,23). In general, metastatic cancers with an unknown primary site are not uncommon and may pose an extremely frustrating problem. They were ranked as the eighth most common site of cancer in a large series of cases accounting for 10% to 15% of referred patients with solid tumors (24,25). In a study of 1,539 patients with an unknown primary cancer, melanomas represented 2.9% of cases (26). The male-to-female ratio was 1.6:1.0 and the median age was 48 years (no patient was younger than 15 years) in a series of 166 cases of lymph node metastases with an unknown primary (20). In descending order of frequency, the lymph node groups involved by metastatic melanoma were axillary (47%), inguinal (20%), and cervical (24%). In women, inguinal metastases were almost as common as axillary metastases (15). The 5- and 10-year survival rates of patients with lymph node metastatic melanoma were 46% and 41%, respectively. These were not influenced by age of the patient, size of the metastases, or pigmentation (melanotic vs. amelanotic). However, patients with axillary metastases had consistently better survival rates than those with metastases in other locations (20). Patients with metastases to a single lymph node had significantly better 5-year survival rates than those with more than one involved lymph node (21). In a retrospective study of 3,805 patients

with melanomas at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, 166 had no known primary tumor, a prevalence of 4.4% (20). The 5-year survival rates of patients who had metastatic melanoma in one group of regional lymph nodes and were treated by lymphadenectomy were similar for those with a known and those with an unknown primary (22). This finding, subsequently confirmed by others (23), suggests that the occult primaries must have been melanomas that regressed, precluding the occurrence of additional metastases. A rare exception is a primary melanoma in a lymph node arising from a prior lymph node nevus, documented in a case report (28).

with melanomas at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, 166 had no known primary tumor, a prevalence of 4.4% (20). The 5-year survival rates of patients who had metastatic melanoma in one group of regional lymph nodes and were treated by lymphadenectomy were similar for those with a known and those with an unknown primary (22). This finding, subsequently confirmed by others (23), suggests that the occult primaries must have been melanomas that regressed, precluding the occurrence of additional metastases. A rare exception is a primary melanoma in a lymph node arising from a prior lymph node nevus, documented in a case report (28).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree