Nomenclature and Classification of Lymphomas

Traditionally, tumors of various organs have been named and classified according to their histogenesis. This concept is based on the assumption that tumors originate in the cells and tissues that they resemble morphologically, and further, that the degree of resemblance indicates the stage of tumor-cell differentiation as reflected in the qualifiers “well” and “poorly differentiated.”

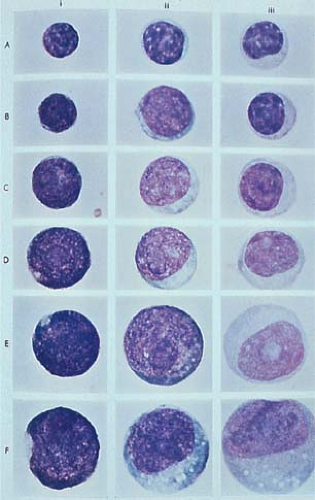

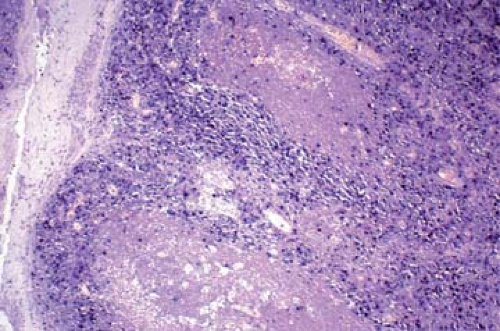

In the past two decades, the rapid progress achieved in immunology and molecular biology has led to important discoveries related to the origin and function of lymphocytes. These in turn were reflected in conceptual changes in the nomenclature and classification of lymphomas. The earlier observation that small, mature-looking circulating lymphocytes, when stimulated by lectins or antigens (4), can transform into large, immature-looking blast cells involved in DNA synthesis and mitotic activity (Fig. 56.2) brought into question the appropriateness of estimating cellular differentiation on the basis of morphology alone (5). Activated lymphocytes or immunoblasts that, according to their size and structure, in the past were considered to represent reticulum cells, histiocytes, or primitive stem cells are, in fact, transformed lymphocytes engaged in protein production and immune activity. Similarly deceiving are small lymphocytes, which appear as “mature, well-differentiated, end-of-the-line cells,” yet can change both their structure and function to the level of primitive blast cells (see Figs. 1.12 and 1.13).

The heterogeneity of lymphocytes is another major discovery that has made a lasting impact on our understanding of lymphomas (6,7). With the aid of newly developed methods, T- and B-cell types of lymphocytes can be identified, and subpopulations of these groups can be recognized by their surface markers and secretory products. Again, the microscopic appearance of cells is deceiving, because distinct populations of lymphocytes may be morphologically indistinguishable.

In the 1970s, numerous investigators applied modern immunologic methods to the study of lymphoma, resulting in important contributions to the recognition of new types of neoplasms (5,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18). Before this, the classification of Rappaport (Table 56.1) (18) had been used internationally since its publication in 1966, having received broad acceptance for its high reproducibility and good clinicopathologic correlations (18). Lukes and Collins (5,19) and Lennert and associates (8,20) were the first to develop classifications based on the evidence of lymphocyte transformation and on the existence of the T- and B-cell systems. Subsequent additional classifications were proposed, considerably increasing the terminology used in this field (21,22,23,24). The large number of publications on lymphomas has added to the inherent complexity of the subject, making the understanding of this group of neoplasms particularly difficult. The classic Rappaport classification was modified to include newly described entities and to correct terms such as nodular lymphoma and histiocytic lymphoma, which were no longer in agreement with the new conceptual changes (24). Lukes and collaborators, in multiparameter studies of large numbers of cases correlating morphologic features with immunophenotypes, showed that, in the Western world, most NHLs—between 75% and 81% in their series—are of B-cell origin, a conclusion confirmed by all subsequent studies (25,26,27). The Kiel classification, based on the concepts introduced by Lennert, was updated to incorporate new data on histogenesis, morphology, and immunologic cell function (28). The Kiel classification was widely used in Europe, but remained largely unfamiliar in the United States. The classification published in 1976 by the World Health Organization was criticized for reintroducing previously abandoned histogenetic terms (23). The British classification proposed by Bennett et al. (21), and classifications by Dorfman (22) and by Mann et al. (29), replaced many of the discredited histogenetic names with new terms and definitions yet did not achieve broad acceptance.

The profusion of nomenclatures and classifications has contributed to the forbidding image of lymphomas, an idea that not infrequently discouraged their study. The lack of agreement and the use of different classifications in textbooks, laboratory investigations, and clinical trials prevented effective communication between workers in the field, and particularly between pathologists and clinicians. Yet, as a critical analysis of this subject by Nathwani pointed out, there were far more similarities than differences between the various classifications in use, which indicated the possibility of achieving consensus on

one classification system (30). A major effort in this sense was the elaborate study of 1,175 NHLs by a panel of international experts, which resulted in a new classification known as the Working Formulation for Clinical Usage (Table 56.2) (31). The NHLs were categorized according to the classifications most commonly used at the time. A large part of the nomenclature used by the Working Formulation was derived from the concepts of Lukes and Collins (19). As previously attempted by Lennert’s group (8), it added an important clinical feature by

dividing the lymphomas into low-, intermediate-, and high-grade categories, which have prognostic implications. The stated goal at the time of its publication was that the Working Formulation was proposed, not as a new classification, but as a means of “translating” among the various systems in existence, to facilitate clinical comparisons of case reports and therapeutic trials (31). In the years since 1982, mainly due to its clinical correlations, the Working Formulation became the classification of NHLs generally used in the United States and in many other countries.

one classification system (30). A major effort in this sense was the elaborate study of 1,175 NHLs by a panel of international experts, which resulted in a new classification known as the Working Formulation for Clinical Usage (Table 56.2) (31). The NHLs were categorized according to the classifications most commonly used at the time. A large part of the nomenclature used by the Working Formulation was derived from the concepts of Lukes and Collins (19). As previously attempted by Lennert’s group (8), it added an important clinical feature by

dividing the lymphomas into low-, intermediate-, and high-grade categories, which have prognostic implications. The stated goal at the time of its publication was that the Working Formulation was proposed, not as a new classification, but as a means of “translating” among the various systems in existence, to facilitate clinical comparisons of case reports and therapeutic trials (31). In the years since 1982, mainly due to its clinical correlations, the Working Formulation became the classification of NHLs generally used in the United States and in many other countries.

Figure 56.1. Epstein-Barr virus-encoded RNA strongly positive in the nuclei of tonsil in infectious mononucleosis. Epstein-Barr virus-encoded RNA in situ hybridization (EBER). |

TABLE 56.1 CLASSIFICATION OF NON-HODGKIN LYMPHOMAS | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

TABLE 56.2 A WORKING FORMULATION OF NON-HODGKIN LYMPHOMAS FOR CLINICAL USAGE: RECOMMENDATIONS OF AN EXPERT INTERNATIONAL PANEL | ||

|---|---|---|

|

In the past two decades unprecedented technological progress made possible detailed analyses of cellular biochemistry, immunology, and genetics. Materials and methods for probing nuclear DNA, determining immunophenotypic profiles, and detecting chromosome translocations became available and led to expanded knowledge and improved diagnosis. In the field of lymphomas, the existence of new populations of lymphoid cells was recognized, and new types of neoplasms were described. Among these were mantle cell lymphoma and marginal zone lymphomas as new types of B-cell neoplasms, and peripheral T-cell lymphoma, adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, and anaplastic large-cell lymphoma as new types of T-cell neoplasms.

Including the newly described forms of lymphomas in the existing classifications proved difficult: awkward terms and ambiguous categories, noted by various authors, often resulted (32,33). To incorporate the new knowledge, an updated Kiel classification, in which the NHLs are divided into B- and T-cell types, was published in 1989 (Table 56.3) (28). However, criticism was directed at the reproducibility of diagnosis and the clinical relevance of the group of T-cell lymphomas in the updated Kiel classification (32).

Changes in the Working Formulation, originally a purely morphologic classification, were also advocated to account for new entities and to reflect the immunophenotypes of lymphomas. But here, again, the B-cell lymphomas proved easier to include, because at the time of its creation the Working Formulation was defined in accordance with already known categories of B-cell lymphomas. In the case of the later described T-cell lymphomas, the maturation scheme of normal T-cell counterparts on which the classification rests was far less defined.

In 1994, an international group of hematopathologists with particular interest and expertise in lymphomas published a proposal for a new classification of lymphomas under the title: A Revised European-American Classification of Lymphoid Neoplasms: A Proposal from the International Lymphoma Study Group (34) (Table 56.4). Generally known by its acronym REAL, the new classification has been widely publicized and generally accepted on both sides of the Atlantic. As stated in its introduction, the REAL classification was not based on the histogenesis of lymphoma cells. Although this would be a desirable mode for a scientific classification, it is recognized that this is not entirely possible at present. Not all types of lymphomas can be traced to specific stages in the differentiation of normal lymphoid cells and, not infrequently, some well-defined lymphomas cannot be matched to any normal cell counterpart. Instead, the REAL classification took the practical approach of categorizing lymphomas not by their presumed cell of origin but by their morphologic, immunologic, and genetic features. In this way, the REAL classification became “a list” of well defined clinicopathologic entities (34). Some categories were provisional depending on further progress in their definition; others that did not fit into the categories of the list “are best left unclassified, reflecting the fact that we do not yet understand completely lymphomas or the immune system” (34). In the future, newly recognized entities can be readily added to the list. The REAL proposal raised some concerns among clinicians, who argued that a classification based on the separation of lymphomas according to their origin as B cells or T cells is not clinically useful (35,36). They also were concerned about some entities that had no good clinical correlation, as well as the fact that identification of various entities in many cases relied on specialized techniques, such as molecular pathology and cytogenetics, that are not widely available (35,36). Some pathologists expressed concerns relative to inconsistencies in the nomenclature, in the absence of tumor grading, and in the equal listing of frequent and rare types of lymphomas (37). However, the REAL classification presented important advantages, among them the inclusion of newly described types of lymphomas, the definition of generally recognized clinicopathologic entities, and the unification of American and European classifications. Although generally based on the updated Kiel classification, the REAL proposal also had features of the Lukes-Collins classification, thus conferring on it an international character. To evaluate the reproducibility and clinical relevance of the REAL proposal, a study of 1,403 cases of NHL at nine locations around the world was organized and classified by five expert hematopathologists (38). Using the new classification, a diagnostic accuracy of 85% and a reproducibility of diagnosis of 85% were achieved for the major lymphoma types. Immunophenotyping improved the diagnostic accuracy by 10% to 45% for some types of lymphoma (38). These results were considered satisfactory for the practical use of the proposed classification. Subsequently, the REAL classification (with modifications suggested by the clinical study) was adopted as the new WHO classification of lymphomas and is presently used world wide (Table 56.5) (39).

TABLE 56.3 UPDATED KIEL CLASSIFICATION OF NON-HODGKIN LYMPHOMAS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TABLE 56.4 LIST OF LYMPHOID NEOPLASMS RECOGNIZED BY THE INTERNATIONAL LYMPHOMA STUDY GROUP | ||

|---|---|---|

|

TABLE 56.5 WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION CLASSIFICATION OF LYMPHOID NEOPLASMS | |

|---|---|

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree