Definitions

A merger is a “combination of two or more companies, either through a pooling of interests, where the accounts are combined; a purchase, where the amount paid over and above the acquired company’s book value is carried on the books of the purchaser as goodwill; or a consolidation, where a new company is formed to acquire the net assets of the combining companies.” An acquisition

is “one company taking over controlling interest in another company” (

US Congress Office of Technology Assessment 1991).

A pharmaceutical company may consider merging with another company for any of a number of reasons. These reasons can be classified into two groups: (a) general industry-wide concepts and (b) company-specific reasons.

General Industry Concepts that Promote Mergers

Some of the general concepts that encourage pharmaceutical companies to merge are independent of the specific companies involved. These include the “bigger is better” concept, the “only the large will survive” concept and the “we’re in trouble and need to fill or expand our pipeline” concept.

Many professionals accept the common belief that “bigger is better” when it comes to pharmaceutical companies. Implicit in this belief is the notion that economies of scale and greater efficiencies are present in very large companies. The advocates of this belief reject the concept that companies have an optimal size that they should not grow beyond. A related corollary is the idea that stockholders reject the concept of limiting growth and wish companies to grow as large as possible in terms of their profits because any cap on growth eventually places a cap on profits.

Many people both within and outside the pharmaceutical industry have the attitude that only extremely large pharmaceutical companies will survive current and future pressures and, ultimately, prosper as research-based companies. These pressures come from many sources, including regulatory authorities, legislators, other companies, and consumer advocates, although there are some who deny this principle. A merger helps ensure that the new larger company will be a survivor in this hostile environment—even though the new company may survive in an altered form and in an industry that is itself greatly altered.

Given the shrinking of the portfolio of many large companies over the past decade, there has been increased focus on trying to identify blockbusters at an earlier and earlier stage so that the company can acquire the rights to many projects of high commercial value to keep its pipeline full. Of course, the number of approved drugs of high medical and also commercial value has shrunk over the past decade and this has increased the importance of a company’s search for both partners and acquisition targets.

Specific Company Factors that Promote Mergers or Acquisitions

Some or all of the following more specific reasons may operate for a company considering a merger. Each reason should be evaluated in terms of the strengths and weaknesses of the two independent companies and also of the single, combined group that will result. This analysis will facilitate a judgment on the quality of the proposed match and the degree of fit.

Many of the following specific goals might be achieved through a merger. These goals may be summarized as searches for (a) increased productivity in research, development, and marketing; (b) greater efficiencies in conducting business (overlapping programs and unneeded positions are eliminated or reassigned); and (c) improved company strengths that increase the likelihood of surviving a hostile regulatory and commercial environment.

To improve the company’s cash flow situation. One of the companies may have chronic (or just acute) cash flow problems and is seeking a partner who has sufficient money to invest in worthwhile projects. The cash-rich company may need something the poorer company has. This may be (a) research staff, (b) manufacturing facilities, (c) well-trained sales force, (d) valuable portfolio of marketed drugs, (e) valuable portfolio of investigational drugs, (f) experienced management team, (g) tax incentives, or (h) something else. Alternatively, the earnings of a pharmaceutical company may fluctuate from year to year more than is desirable and a merger with a wealthy partner is viewed as a means of preventing or at least reducing this fluctuation.

To improve the size of the company’s sales force. A merger is a rapid means of increasing the size of a company’s sales force, particularly when the company that seeks to gain the larger sales force has something of value to the other to bring to the negotiations. Various pressures may exist in other areas of marketing that encourage the merger (e.g., long history of successful marketing and launches of projects).

To improve the quality of the company’s portfolio of drugs. This may be with regard to marketed or investigational drugs, or with regard to prescription or over-the-counter drugs. Given the escalating costs of conducting research and development, a merger may help bring this aspect under greater control through the development of only those projects of highest medical and commercial value.

To improve technical expertise or to increase the number of professional staff in important areas. A common example of this type of acquisition is for a large pharmaceutical company to acquire a biotechnology firm. This has colloquially been referred to as “achieving critical mass,” a popular term for having sufficient capability to conduct a defined set of activities. Most companies have a different idea about what quantity of staff is necessary to achieve a critical mass, and also what activities one should be able to handle within the organization. Given the increasing complexity of innovation in discovery research, it is progressively more difficult to attract and retain top-class creative researchers in all disease areas being investigated.

To increase the number of therapeutic or disease areas the company can research. A merger with a company that has experienced and productive staff actively conducting research in different therapeutic areas is a rapid means of expanding into new areas and increasing the chances of making a new discovery.

To expand the geographic scope of the company. A company may desire to expand its operations into new territories but has not done so for various reasons. The merger may be a straightforward means to achieve this goal.

To expand the number of businesses that the company is engaged in. The company may seek diversification into new business areas and see the merger as a means of accomplishing this goal.

To form a “whole” pharmaceutical company. Two companies focused on different activities that complement each other could merge and, thus, be capable of more activities than was possible as single separate entities. For example, a

well-established company that solely licenses in and develops drugs could merge with a company that focuses on research and discovery activities to enlarge the scope of both activities.

To acquire an important technology. A company may adopt the merger approach to acquire an important technology (e.g., drug delivery system, sustained-release formulation, or soft gelatin capsule formulation) rather than license it. The acquisition of a unique technology could provide an important competitive advantage.

Evaluating Partners for a Possible Merger or Acquisition

The initial stage is for a company to have a clear objective or goal in mind that it wishes to achieve through a merger or acquisition, and also a focused strategy of how it is seeking to address that objective. While a company can “fall” into a perfect match by chance, the likelihood of that happening is small. The second stage is to evaluate each organization’s strengths and weaknesses and compare these to the strengths and weaknesses with the combined “parent” company. The major areas to assess are finances, patents, product portfolio of marketed and investigational drugs, market positions in important disease and therapeutic areas in important markets, and the nature of the research and development groups. Although this may be interpreted as an evaluation of the pharmaceutical business, all other businesses owned by the proposed partner must be carefully assessed as well. If there are redundant assets can they be disposed of readily? The cultures of the two organizations must be carefully considered, whether the merger is friendly or represents a hostile takeover. Surprisingly, there have been recent mergers between French and

US companies that have worked out better than mergers between two American companies where there was a major clash in corporate cultures (i.e., one company was more regimented and the other extremely informal).

Alternatives to a Merger or Acquisition

Even when a merger is a suitable option for a company, other alternatives should be considered and evaluated. Five alternatives are:

Strategic alliances. The term strategic alliance is a general one and includes alternatives 3 and 5. Formal alliances with other companies or institutions can provide a company with some of the benefits of a merger without many of the risks. This approach is discussed later.

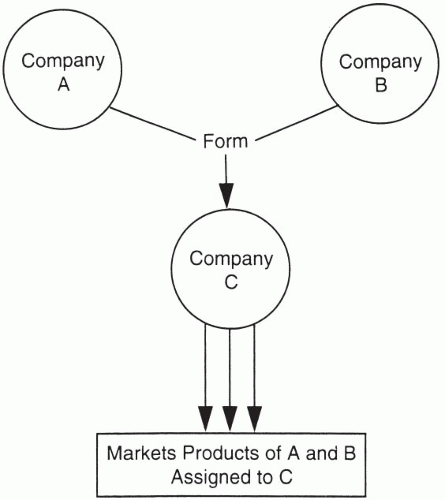

Form a separate company. A company that wants to preserve its identity, size, and culture may expand boldly using this approach as modeled in

Fig. 27.1. The parent company could “divest” itself of one or more of its ancillary business activities that might flourish in this new relationship. Alternatively, the new company could be allowed to remain in the pharmaceutical business along with one or both parents.

Comarket an important product. Joint marketing activities can greatly enhance sales and commercial benefits for appropriate products. This subject is also discussed later.

Purchase a subsidiary. This could be done to achieve the type of experience or technology (e.g., biotechnology) sought in the merger. A biotechnology company could be purchased and retained as a subsidiary. One advantage of this approach is that it retains the scientific expertise within the company for consulting, biological manufacturing, or other needs.

Loose or tight alliance. This alternative is really a joint venture. A valuable advantage could be gained by two companies from different cultures (e.g., France and the United States or Japan and England) agreeing to work together on many joint projects, but not to exchange any capital. Each company would preserve its cash flow in the major markets, but would be able to (or would be committed to) enter more and more projects as partners.