21 Mental and Behavioral Health

Depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, and substance abuse are prominent among the mental health and behavioral disorders. Affecting more than 450 million people worldwide and associated with substantial morbidity and mortality,1 these disorders are critical targets for prevention efforts because of their toll on individuals and society.

I Mental Health/Behavioral Disorders and Suicide

A Definitions

Mental Health Disorder

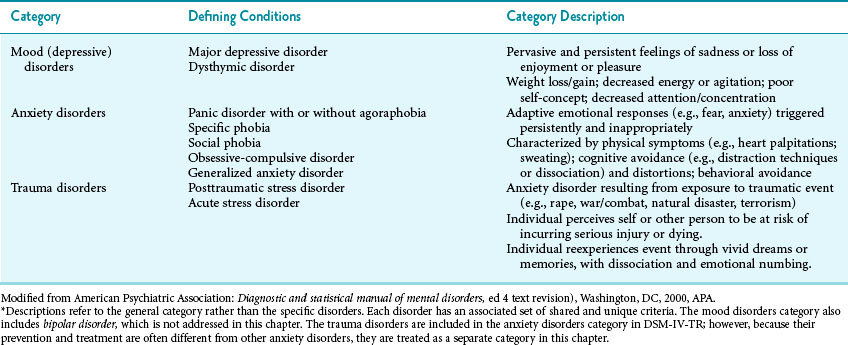

Mental health disorder is a broad term that refers to a set of emotions, cognitions, and behaviors that cause distress to individuals or others, are abnormal from the perspective of the society or culture, and result in harm to self or others or in functional impairment in one or more domains (i.e., work, school, home).2 Within the broader category of mental health disorder are emotional disorders that cross Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) diagnostic categories.2 The most prevalent of the emotional disorders, and therefore the most costly to individuals and society, are depression and anxiety.1 Table 21-1 outlines mood (depressive), anxiety, and trauma disorders, the mental health disorders that are the focus of this chapter.

Behavioral Disorders

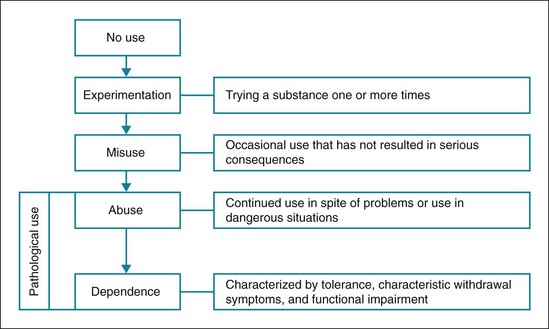

Substance use, both licit (e.g., alcohol, tobacco) and illicit (e.g., cocaine, heroin), varies along a continuum3 (Fig. 21-1). Misuse of a substance is often indicative of a risk for more pathological use. Pathological use may be characterized by continued substance use despite serious consequences (e.g., HIV infection, incarceration), tolerance (need to take more of a substance to experience its customary effects), and withdrawal.2

Such behaviors often appear compulsive (outside the individual’s control).

Such behaviors often appear compulsive (outside the individual’s control).

Participation is continued despite experiencing serious negative consequences.

Participation is continued despite experiencing serious negative consequences.

The same neural circuitry responsible for substance addiction is also involved in excessive pursuit of these behaviors.4

The same neural circuitry responsible for substance addiction is also involved in excessive pursuit of these behaviors.4

Research also suggests that substance and behavioral addictions are highly comorbid.5 Although strong evidence supports the inclusion of pathological gambling and excessive Internet use within the broader category of addictive disorders, evidence supporting other behavioral addictions (e.g., kleptomania, sexual addiction) is less compelling.5 However, others consider the evidence in support of the food addiction concept, specifically as it relates to compulsive overeating and bulimia,4 to be compelling.6 Obesity is discussed in Chapter 19.

Suicide

Suicide is a purposeful act directed toward ending one’s life. Whereas suicide is intended to refer to successful completion of the act, the term suicide attempt is intended to refer to any act of self-harm, including parasuicidal behavior such as cutting, regardless of the intent of the behavior or the outcome. Suicidal ideation refers to thoughts about killing or harming oneself.7

B Epidemiology

Mental Health Disorders

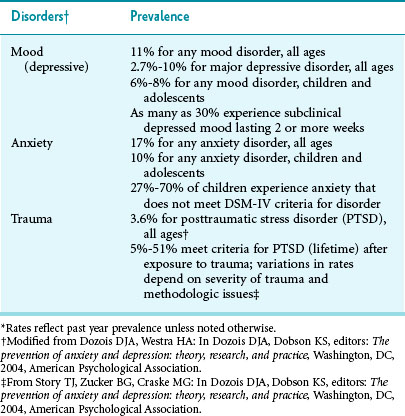

Mental health disorders affect a large segment of the U.S. population. Research suggests that about one in five adults (age 18 or older) met criteria for a mental health disorder in the past year.8 Table 21-2 outlines prevalence estimates for mood (depressive), anxiety, and trauma disorders.

Behavioral Disorders

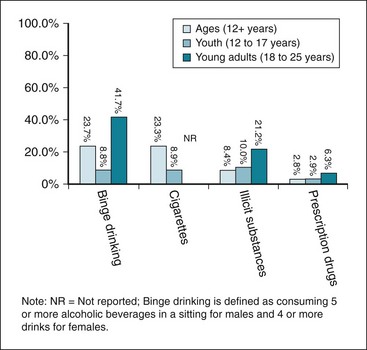

Figure 21-2 presents rates of licit and illicit substance use. Among licit substances, alcohol is most often used, with 52% of individuals age 12 or older reporting tobacco use in the past year, followed closely by tobacco products, used by 28% of individuals age 12 years and older.9 While not as prevalent as alcohol and tobacco, illicit substances are used at alarming rates and include marijuana, cocaine, heroin, and amphetamines. Evidence indicates abuse of prescription medications (i.e., use for nonprescribed purposes such as “getting high” or to help study) has been increasing in recent years.10,11

Figure 21-2 Past-month prevalence estimates for substance use, 2009.

Binge drinking, cigarette smoking, illicit substances, and prescription drug use in persons age 12 and older, adolescents age 12-17, and young adults age 18-25.

(Modified from Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, Rockville, Md, 2010, Office of Applied Studies; and National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism: NIAAA council approves definition of binge drinking.)

Among behavioral addictions, pathological gambling is estimated to affect 1% to 2% of the U.S. population. Sexual behavior considered pathological is estimated to affect 5%. In regard to problematic Internet use, whereas 6% of users can be considered addicted, this represents less than 1% of the U.S. population. Eating or food addictions are believed to affect 3%, with women affected more often than men.11

Concurrent Mental Health and Behavioral Disorders

There is a high degree of comorbidity among mental health disorders and between mental health and behavioral disorders. Specifically, anxiety and depression are present concurrently in about 50% of patients.12 Among substance-dependent individuals, 60% to 80% of adults and 60% of youth have a comorbid mental health disorder. Moreover, approximately 25% to 30% of depressed and anxious adults meet criteria for a substance use disorder.13 Behavioral addictions (e.g., gambling, overeating, Internet overuse) are often associated with other behavioral and drug addictions, as well as psychiatric disorders.11

Suicide

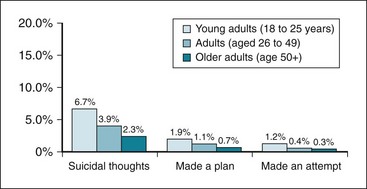

Suicide accounted for more than 32,000 adult deaths in the United States in 2006. Many more adults have serious thoughts about killing themselves than make a suicide plan or attempt suicide. Research also suggests that for every one successful suicide, there are as many as 20 attempts.1 Among youth, estimates suggest that between 9.4% (ages 12 to 13) and 12.7% (ages 14 to 17) were at serious risk for suicide by virtue of having had serious suicidal ideation or having made a previous attempt. Among those at high risk, 37% made a suicide attempt in the past year14 (Fig. 21-3).

Figure 21-3 Past-year prevalence estimates for suicidal ideation, 2008.

Serious suicidal thoughts, making plans for suicide, and suicide attempts in young adults age 18-24, adults age 26-49, and older adults 50 and older.

(From Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among adults: the NSDUH report, Rockville, Md, 2009, Office of Applied Studies. http://www.samhsa.gov/data/2k9/165/Suicide.htm)

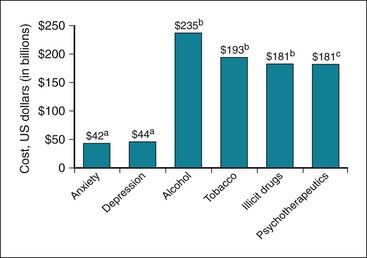

C Costs

Mental health and behavioral disorders are extremely costly to society (Fig. 21-4). Whereas anxiety and depression costs primarily result from mental health care utilization, the costs associated with substance use disorders include both health care utilization (outpatient treatment; hospitalization) as well as incarceration and interdiction efforts.

Figure 21-4 Overall economic impact of mental health and behavioral disorders.

aAnnual estimate; byear of estimate: 1998 (alcohol), 2007 (tobacco), 2002 (illicit drugs); cyear of estimate: 2002.

(a from Dozois DJA, Westra HA: In Dozois DJA, Dobson KS, editors: The prevention of anxiety and depression: theory, research, and practice, Washington, DC, 2004, American Psychological Association; b from Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: State estimates of substance use and mental health disorders from the 2008-2009 National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, NSDUH Series H-40, HHS Pub No SMA 11-4641, Rockville, Md, 2011, Office of Applied Studies; c from Manchikanti L: Pain Physician 9:289–321, 2006.)

Mental Health Disorders

In addition to economic impacts, mental health disorders are associated with the following1,12:

Behavioral Disorders

Substance use disorders cause significant morbidity and mortality both in the United States and worldwide. Alcohol, tobacco, illicit substances, and prescription medications are all responsible for a substantial number of avoidable deaths because of their deleterious health effects. Specifically, excessive use of both licit and illicit substances is associated with cardiovascular disease and many different types of cancer.1

By impairing attention, concentration, and judgment, alcohol consumption is believed to be a causal factor in risky sexual practices,15 increasing the risk of unwanted pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), aggressive behavior, and fatal motor vehicle crashes.1 Smoking during pregnancy is associated with premature birth as well as low birth weight, which increase the risk for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), conduct problems, and poor school achievement.9

Nonprescription use of medications accounts for a substantial number of emergency department admissions and overdoses.10 Illicit substance use significantly increases the risk of contracting infectious diseases (e.g., HIV, hepatitis B) through injection/intravenous drug use (IDU)16 or risky sexual practices with infected partners. Drug use during pregnancy is associated with withdrawal symptoms among infants after birth and an increased risk of offspring developing substance use disorders.1

II Risk and Protective Factors

Whereas some may be directly modifiable through education or treatment (e.g., negative thinking), other risk factors (e.g., temperament) may not. However, some suggest that a diathesis-stress model may serve as the most useful framework for understanding the development of mental health disorders19 and behavioral problems. This model suggests that preexisting biologic and psychological vulnerabilities predispose a vulnerable individual to problematic emotions and behaviors when facing stress that exceeds one’s ability to cope. Thus, it is important to be able to recognize these nonmodifiable factors because they may help identify those most in need of prevention and intervention efforts.

A Biologic Risk Factors

Genetics have been found to account for 30% to 40% of an individual’s risk for anxiety and depression20,21 and 50% to 60% of risk for substance dependence (although heritability estimates for drug dependence are more variable than for alcohol dependence). Research on genetics of addiction suggests that although environmental factors play a more prominent role in the early stages of use (initiation and misuse), genetics is more influential in the progression to pathological use.22

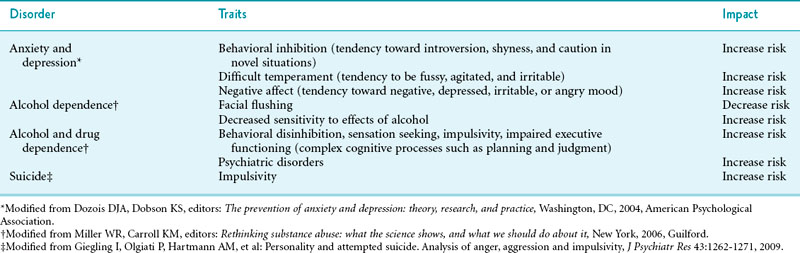

Endophenotypes represent inherited traits that are risk factors for disorder and are both present and detectable before the disorder is expressed. Table 21-3 lists traits that represent possible endophenotypes for mental health and behavioral disorders. Other biologic factors associated with dysphoric mood (either anxiety or depression) include the following:

Hormonal changes (e.g., mood disorder with postpartum onset)2

Hormonal changes (e.g., mood disorder with postpartum onset)2

Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS), associated with a rapid onset of tics, Tourette’s syndrome, and obsessive-compulsive disorder in children23

Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS), associated with a rapid onset of tics, Tourette’s syndrome, and obsessive-compulsive disorder in children23

Amount of daylight (e.g., mood disorder with seasonal pattern)2

Amount of daylight (e.g., mood disorder with seasonal pattern)2

Table 21-3 Inherited Temperaments or Traits Indicative of Risk for Anxiety, Mood (Depressive), and Substance Use Disorders

The pharmacologic properties of drugs explain why they are used. In particular, users often report that they use substances “to feel good, to feel better, to alter consciousness,”3 and to do better (e.g., steroids to enhance physical performance; prescription stimulants to enhance academic performance).

The presence of one disorder may be a risk factor for another. Specifically, anxiety often precedes, and thus may be a causal factor in, the development of depression.25,26 Externalizing disorders during childhood (e.g., conduct disorder, ADHD) are associated with an increased risk of substance use problems that persist into adulthood.27 Other potential associations between psychiatric and substance use disorders include the following:

Pathological substance use causes anxiety, depression, and other mental health disorders by increasing stress or impacting sensitive neural systems.

Pathological substance use causes anxiety, depression, and other mental health disorders by increasing stress or impacting sensitive neural systems.

Anxiety, depression, and other mental health disorders cause pathological substance use because substances help to regulate negative moods.

Anxiety, depression, and other mental health disorders cause pathological substance use because substances help to regulate negative moods.

Psychiatric and substance use disorders share genetic risk factors (e.g., difficult temperament, negative affectivity) and other risks (e.g., maladaptive responses to stress, lack of adequate coping mechanisms).

Psychiatric and substance use disorders share genetic risk factors (e.g., difficult temperament, negative affectivity) and other risks (e.g., maladaptive responses to stress, lack of adequate coping mechanisms).

Psychiatric and substance use disorders reciprocally influence one another.13

Psychiatric and substance use disorders reciprocally influence one another.13

B Psychological Risk Factors

Individuals’ thoughts, beliefs, expectancies, and self-perceptions are shaped through an interaction of inherited temperaments, sensitive neural systems, hormones, and early learning experiences and thereby influence the development of mental health and behavioral disorders. Thus, both depression and anxiety are associated with maladaptive thought patterns, although the content of the maladaptive thoughts associated with anxiety and depression differs.25,26 Similarly, beliefs about the effects of a substance, known as outcome expectancies, influence the age of onset and level of substance use. Positive expectancies (beliefs that drinking will produce positive outcomes) are associated with increased use, but negative expectancies do not appear to deter use.27 Moreover, one explanation for the increase in nonmedical use of prescribed medications includes the perception that such drugs are safer than illicit substances and pose no serious health risks.10

The extent to which an individual believes that others would benefit from the person’s death (“perceived burdensomeness”) and that the individual’s basic needs for affiliation are not being met (“thwarted belongingness”) are risk factors for suicidal ideation.28 Suicide risk increases when suicidal thoughts are combined with an increased acceptance of suicide as a viable option and feelings of hopelessness. One of the best predictors of future suicide attempts is past suicidal behavior.29

C Social Risk Factors

Among vulnerable individuals, exposure to anxious parents30 or to substance-using peers27 increases the risk of developing an anxiety or substance use disorder, respectively. Parental depression significantly increases the risk of depression among offspring, perhaps from poor communication, lack of emotional availability and bonding, or family disruption.31 Direct exposure to a threatening stimulus (e.g., trauma, social evaluation) will also lead to the development of specific phobias and traumatic stress disorders.30 Direct-to-consumer advertising of psychotherapeutics may play a role in perceptions of these drugs and nonmedical use.10 Excessive attention and glorification of suicides in the media are believed to increase the risk for “copycat” behavior.32

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree