Medullary Carcinoma

FREDERICK C. KOERNER

Mammary carcinomas have been described as “medullary” for nearly a century. Initially, the term was employed clinically and pathologically for large, solid carcinomas with a papillary or fleshy macroscopic appearance. Included in this group were tumors characterized by a marked lymphoid reaction and a favorable prognosis referred to as cystic neomammary carcinoma by Geschickter.1 At Memorial Hospital in New York City, these tumors were termed “bulky adenocarcinomas” until the name “medullary carcinoma” was proposed in the 1940s.2,3 As classically envisioned, medullary carcinoma is a well-circumscribed carcinoma composed of poorly differentiated cells with scant stroma and prominent lymphoid infiltration. The term atypical medullary carcinoma was introduced in 19754 to describe carcinomas that have features generally suggestive of medullary carcinoma but lack one or more of the defining histologic characteristics. These tumors are now classified as invasive ductal carcinomas with medullary features.

The diagnosis of medullary carcinoma seems to have lost favor during the past decade or two. Many pathologists, including those at large referral centers, feel uncertain about the recognition and the application of the classical diagnostic criteria. A poor level of diagnostic reducibility and uncertainty about the clinical ramifications of this diagnosis add to pathologists’ reluctance to classify carcinomas as medullary. The editors and contributors to the 4th edition of the WHO Classification of Tumours of the Breast recommend that “classic [medullary carcinoma], atypical [medullary carcinoma], and invasive carcinoma NST with medullary features be grouped within the category of carcinomas with medullary features.”5 The short discussion that follows this recommendation does not offer criteria to distinguish among the members of this group. This movement away from classifying certain carcinomas as medullary seems regrettable and premature. Well-conducted clinical followup studies continue to demonstrate the favorable prognosis afforded by this type of breast carcinoma. It would be a shame to abandon the diagnosis of medullary carcinoma at the moment when contemporary genomic studies offer the hope of a greater understanding of this tumor. Such studies might discover a molecular signature that identifies those members of the group of “carcinomas with medullary features” that have a relatively more favorable prognosis; they might reveal consistent genetic alterations that underlie the formation of medullary carcinomas, and they might elucidate the molecular mechanisms responsible for the favorable clinical behavior of medullary carcinomas. With such information in hand, pathologists could then study the histologic characteristics of these tumors and, possibly, describe a set of robust criteria that define medullary carcinoma. Until investigators have explored this group of tumors at the genetic level, it seems preferable to continue to classify certain carefully characterized carcinomas as medullary.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Frequency

Medullary carcinomas constitute fewer than 5% of most series of breast carcinomas,6,7,8,9,10,11 but frequencies as high as 7% have been reported.12,13,14,15 A review of 524 consecutive patients with T1N0 and T1N1 breast carcinomas treated from 1964 to 1970 found that medullary carcinoma comprised 2% of both groups.16,17

Epidemiology

In epidemiologic studies, medullary carcinoma was detected relatively more frequently in Japanese women in Japan than in Caucasian women in the United States18,19,20 and more commonly in African American women than in Caucasian women in the United States.21,22,23,24 An analysis of data from a large number of women beyond the age of 50 years with breast carcinoma demonstrated an elevated risk of medullary carcinoma among African American and certain groups of Asian and Hispanic women compared with the risk faced by non-Hispanic Caucasian women. Puerto Rican women had the greatest risk, 7.7 times that of non-Hispanic Caucasian women, and Native American women followed with a risk of 4.7 times that of non-Hispanic Caucasian women.25 Maier et al.6 also noted more medullary carcinomas in “non-Caucasians.”

Family History

Maternal breast carcinoma was reportedly more frequent among women with medullary carcinoma than among

women with other types of carcinoma, whereas very few of their sisters had breast carcinoma.26 A detailed analysis of the family pedigrees of patients with medullary carcinoma did not reveal an increased risk of neoplastic disease, including breast carcinoma compared with the families of patients with tubular or invasive ductal carcinoma.27

women with other types of carcinoma, whereas very few of their sisters had breast carcinoma.26 A detailed analysis of the family pedigrees of patients with medullary carcinoma did not reveal an increased risk of neoplastic disease, including breast carcinoma compared with the families of patients with tubular or invasive ductal carcinoma.27

Medullary carcinoma afflicts adults of all ages. Patients as young as 21 years28 and as old as 95 years6 have developed medullary carcinoma. This broad range of ages notwithstanding, patients with medullary carcinoma tend to be relatively young. Moore and Foote3 found that 59% of their patients were younger than 50 years, and in other series, 40%13 and 60%29 of patients were younger than 50 years. The mean age in several series ranged from 45 to 54 years.6,7,9,11,28,29,30,31,32,33 A study of 159 women aged 35 years or less with breast carcinoma found that 11% had medullary carcinomas.34 Medullary carcinoma is relatively uncommon in elderly patients,35 and it occurs in the male breast only very rarely.

Clinical Location of Tumor

The anatomic distribution of medullary carcinoma in the breast does not differ significantly from that of breast carcinomas in general. Multicentricity, defined as microscopic foci of carcinoma outside the primary quadrant, is uncommon in patients with medullary carcinoma. It was found in 10% of 58 cases in one series.36 Medullary carcinoma arising in the axillary tail is difficult to distinguish from metastatic carcinoma in a lymph node.37 Medullary carcinoma is not especially common among patients with bilateral mammary carcinoma. On the other hand, bilateral carcinoma has been found in 3% to 12% of patients with medullary carcinoma.6,8,35,36 Synchronous or metachronous medullary carcinoma involving both breasts is very uncommon.28,36

Clinical Presentation of Axillary Lymph Nodes

Ipsilateral axillary lymph nodes (ALNs) tend to be enlarged on clinical examination in patients with medullary carcinoma even when there are no nodal metastases. This phenomenon, which may complicate clinical staging,38 can also be encountered in patients with invasive ductal carcinomas with medullary features.39 Microscopically, the lymph nodes have a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, germinal center hyperplasia, and sinus histiocytosis. On average, the number of lymph nodes evident in axillary dissection specimens from patients with medullary or atypical medullary carcinoma is greater than for other types of carcinoma.39 This difference probably results from the greater ease of finding enlarged hyperplastic lymph nodes.

Imaging Studies

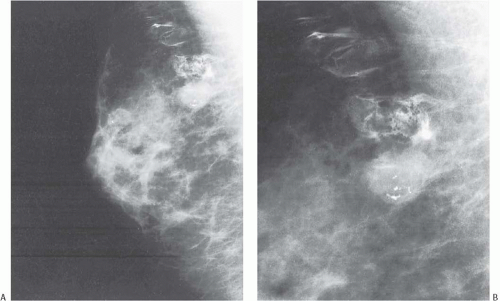

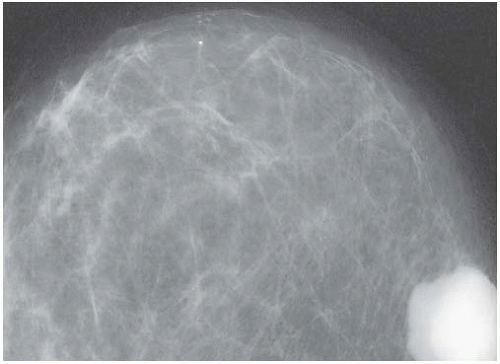

Mammograms of medullary carcinomas typically demonstrate a uniformly dense, round or oval mass with indistinct or lobulated borders and lacking calcifications.40 Because they have circumscribed margins, medullary carcinomas can be mistaken radiologically for fibroadenomas.7,41 The findings apparent on ultrasound studies vary from one case to the next. Medullary carcinoma most commonly displays a hypoechogenic mass with an inhomogeneous echotexture, a microlobulated or indistinct border, and posterior enhancement.40 Medullary carcinomas that have undergone cystic degeneration can exhibit a complex pattern of echoes.41,42 Invasive ductal carcinomas with medullary features tend to have an irregular margin on ultrasonography.42 By magnetic resonance imaging, the carcinomas are iso- or hypointense on T1-weighted images and iso- or hyperintense on T2-weighted images. The masses usually have oval or lobular shapes and smooth borders, and they often exhibit rim enhancement. Time-intensity curves display a rapid initial rise in enhancement and a plateau or washout pattern.40,43 Kopans and Rubens44 and Tominaga et al.43 emphasized that radiologic findings cannot differentiate medullary carcinoma from circumscribed non-medullary carcinoma (Figs. 15.1 and 15.2).

GROSS PATHOLOGY

Early descriptions1,3 of medullary carcinoma emphasized its large size, a characteristic exemplified by the term “bulky carcinoma” once used for this tumor. The passage of time has not improved upon the description written by Drs. Foote and Stewart2: “They are commonly quite bulky, measuring 4, 5 and 6 cm in diameter, and now and then these dimensions are doubled. They are rounded or globoid, cut with little resistance, and although not encapsulated these tumors are distinctly circumscribed and present a smooth periphery. On cut section the exposed surface bulges above the level of the surrounding tissue, the tumor is soft, and chalky streaks are unexpected. Where the carcinoma is fully viable it is grayish white, but as a group these tumors are quite prone to spontaneous hemorrhage and necrosis, and for this reason may present variegated coloring.”

In contemporary times, the size distribution of grossly measured medullary carcinomas is not appreciably different from that of conventional invasive ductal carcinomas (IDC); several series report a median size of 2.0 to 3.2 cm.8,12,28 These smaller examples of medullary carcinoma do not display signs of advanced disease such as ulceration of the skin and fixation to the chest wall as did large, bulky tumors described in the earliest descriptions of medullary carcinoma.

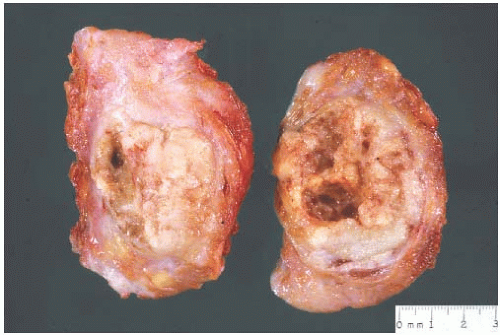

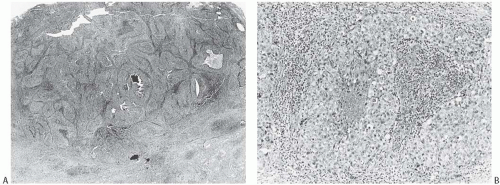

The typical intact medullary carcinoma is a moderately firm discrete tumor that one can easily mistake for a fibroadenoma (Fig. 15.3). A distinct margin outlines the tumor when bisected and distinguishes it from the surrounding breast tissue (Fig. 15.4). In larger lesions, particularly those with prominent cystic areas, peripheral fibrosis may suggest encapsulation (Fig. 15.5). Some small medullary carcinomas have poorly circumscribed borders.30 The peripheral areas of ill-defined medullary carcinomas have an intense lymphoplasmacytic reaction that extends well beyond the perimeter of the carcinoma; consequently, gross circumscription is supportive of but necessary for a diagnosis of medullary carcinoma. Some non-medullary infiltrating

carcinomas are as well circumscribed as typical medullary carcinomas (Fig. 15.6).

carcinomas are as well circumscribed as typical medullary carcinomas (Fig. 15.6).

The cut surface of the fresh specimen and whole-mount histologic sections reveal that a medullary carcinoma has a lobulated or nodular internal structure (Figs. 15.5 and 15.7). One can occasionally find secondary nodules at the periphery of the main tumor or appreciate that the mass is composed of coalescent nodules (Fig. 15.8). The pale brown to gray tumor is softer than the average breast carcinoma, and it tends to bulge above the surrounding parenchyma rather than to display the retracted appearance of the commonplace invasive ductal carcinoma. In 1956, Richardson13 noted that “The tumour tissue looks moister and more succulent than that of

other types of breast carcinoma.” Hemorrhage and necrosis occur at times, even in medullary carcinomas smaller than 2 cm; however, the extent of necrosis is directly related to tumor size: as the extent of necrosis increases, so, too, does the likelihood that the tumor will develop cystic foci (Fig. 15.9). Prominent cystic degeneration is seen only in tumors larger than 5 cm (Fig. 15.10). The necrotic tissue sometimes has a caseous, granular appearance. Fragmented tumor in the cavity of a cystic medullary carcinoma may be grossly indistinguishable from a cystic papillary carcinoma.

other types of breast carcinoma.” Hemorrhage and necrosis occur at times, even in medullary carcinomas smaller than 2 cm; however, the extent of necrosis is directly related to tumor size: as the extent of necrosis increases, so, too, does the likelihood that the tumor will develop cystic foci (Fig. 15.9). Prominent cystic degeneration is seen only in tumors larger than 5 cm (Fig. 15.10). The necrotic tissue sometimes has a caseous, granular appearance. Fragmented tumor in the cavity of a cystic medullary carcinoma may be grossly indistinguishable from a cystic papillary carcinoma.

FIG. 15.2. Circumscribed non-medullary carcinoma, mammography. Histologic examination of the circumscribed tumor revealed an infiltrating duct carcinoma with medullary features. |

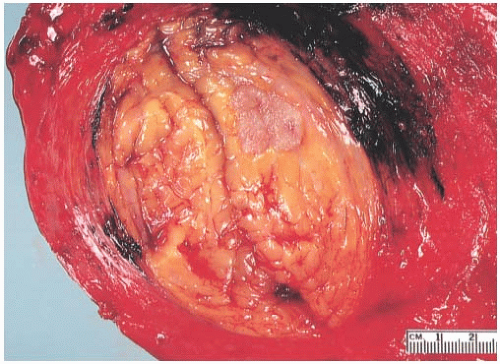

FIG. 15.3. Medullary carcinoma, gross specimen. The nodular tumor has a circumscribed border and lobulated cut surface. |

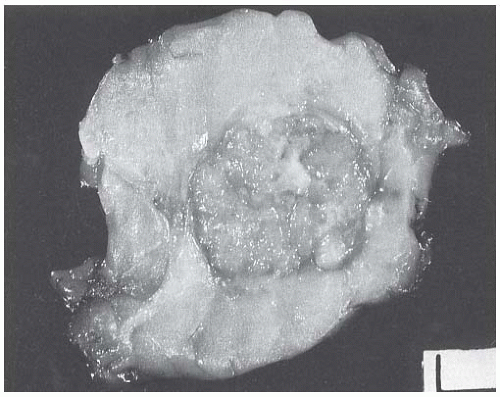

FIG. 15.4. Medullary carcinoma, gross specimen. The tumor protrudes above the surrounding tissue. The borders are circumscribed, and the cut surface reveals internal nodularity. (Reproduced from Rosen PP, Oberman HA. Tumors of the mammary gland. (AFIP Atlas of Tumor Pathology, 3rd series, vol. 7). Baltimore: American Registry of Pathology, 1993, with permission.) |

MICROSCOPIC PATHOLOGY

It is necessary to adhere strictly to defined morphologic criteria if the diagnosis of medullary carcinoma is to be predictive of a relatively favorable prognosis.6,30 The gross appearance of a tumor may lead one to suspect medullary carcinoma, and occasionally this may be taken into consideration in deciding how to classify a lesion with borderline features; however, the diagnosis ultimately depends upon the microscopic characteristics of the tumor. Overdiagnosis of medullary carcinoma has been reported in several reviews. This phenomenon usually results from a failure to limit the diagnosis to lesions that fulfill all diagnostic criteria.8,28,30,45,46

Investigators have reported substantial interobserver and intraobserver variability in the diagnosis of medullary carcinoma.45,47,48 This variation has led to the suggestion that histologic criteria for the diagnosis be modified; however, the favorable prognosis attributed to true medullary carcinoma is not observed in cases classified according to modified criteria.49 Jensen et al.50 compared three systems for defining medullary carcinoma and invasive ductal carcinoma with medullary features. The criteria set forth by Ridolfi et al.30 proved more reliable for detecting survival differences between true medullary, atypical medullary, and non-medullary carcinomas than the modified definitions set forth by Tavassoli51 and by Pedersen.49 Marginean et al.52 also proposed a simplified set of criteria for the diagnosis of medullary carcinoma. The specific diagnosis of medullary carcinoma will be improved by increased familiarity with and strict adherence to the diagnostic criteria already established. In doubtful situations, a tumor should not be classified as a medullary carcinoma.

Medullary carcinoma is defined by a constellation of histopathologic features initially enumerated by Foote and Stewart2 and Moore and Foote.3 These features include prominent lymphoplasmacytic reaction, noninvasive microscopic circumscription, growth in sheets (syncytial pattern), poorly differentiated nuclear grade, and a high mitotic rate. A tumor must display all of these definitive characteristics to be classified as a medullary carcinoma. When most but not all of the needed components are present, the tumor may be termed an IDC with medullary features. Tumors in this category have a syncytial growth pattern and certain other histologic features of medullary carcinoma, but deviate from the definitive appearance by demonstrating one or more of the following structural variations: invasive growth at the periphery; sparse or diminished lymphoplasmacytic reaction; well-differentiated nuclear cytology; low mitotic rate; and conspicuous glandular, trabecular, or papillary growth with fibrosis. Invasive ductal carcinomas with medullary features can display immunohistochemical findings seen in typical medullary carcinomas, but they do so less frequently.

Lymphoplasmacytic Infiltrate

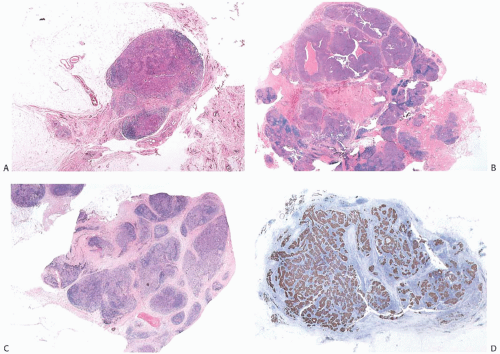

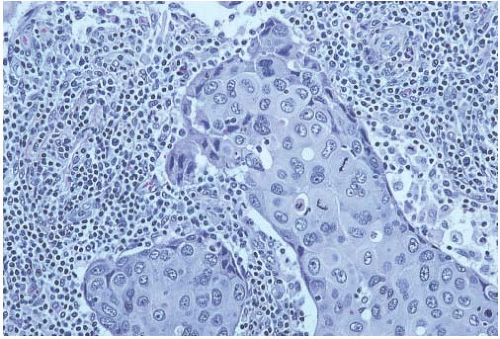

The lymphoplasmacytic reaction must involve the periphery and be present diffusely in the substance of the tumor. In most medullary carcinomas, the internal lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate tends to be limited to fibrovascular stroma

between syncytial zones of tumor cells. A minority of medullary carcinomas seem to be largely devoid of stroma, and the lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate mingles intimately with carcinoma cells12 (Fig. 15.11). Pathologists sometime refer to such lesions as lymphoepithelioma-like carcinomas. One can find it difficult to differentiate such a tumor from metastatic carcinoma in a lymph node.

between syncytial zones of tumor cells. A minority of medullary carcinomas seem to be largely devoid of stroma, and the lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate mingles intimately with carcinoma cells12 (Fig. 15.11). Pathologists sometime refer to such lesions as lymphoepithelioma-like carcinomas. One can find it difficult to differentiate such a tumor from metastatic carcinoma in a lymph node.

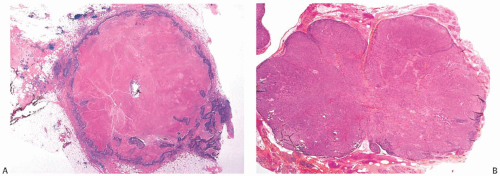

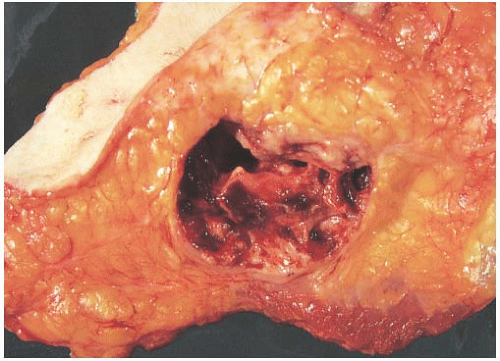

FIG. 15.10. Medullary carcinoma, cystic. The gross appearance of the tumor in a mastectomy specimen. |

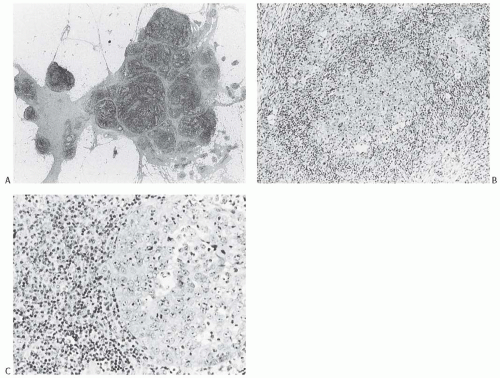

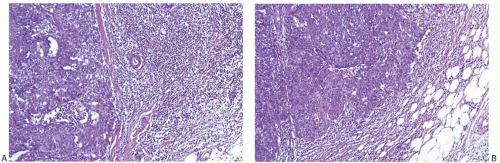

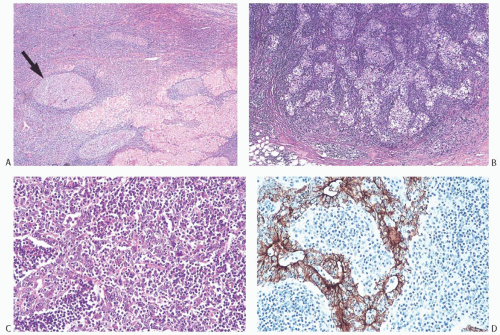

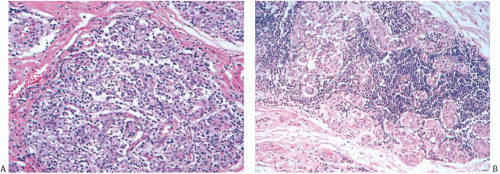

FIG. 15.11. Medullary carcinoma, lymphoplasmacytic reaction. A: Syncytial sheets of carcinoma cells surrounded by a diffuse lymphocytic reaction. The germinal center is an unusual occurrence (arrow). B: Lymphocytic reaction around groups of carcinoma cells in nodular aggregates. C: Lymphocytic reaction mingles with and obscures the carcinoma cells, creating an appearance that resembles lymphoepithelioma. D: The carcinoma cells are highlighted with the CK immunostain. |

At the periphery of the tumor, there may be some variation in the amount of lymphocytic reaction, but it should be at least moderately intense at the interface of the carcinoma with mammary parenchyma and in the adjacent tissue. In the usual case, the lymphoplasmacytic reaction encompasses surrounding ducts and lobules occupied by in situ carcinoma (Fig. 15.12). The reactive process also tends to involve more distant ducts and lobules, which do not contain identifiable tumor cells (Fig. 15.13). These secondary peripheral alterations are so common in medullary carcinoma that the diagnosis may be questioned when they are absent.

The lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate may be composed almost entirely of either lymphocytes or plasma cells, but most often there is a mixture of these cells12 (Fig. 15.14). Bässler et al.12 reported that lymphocytes predominated at the periphery of medullary carcinomas, whereas plasma cells represented the preponderant inflammatory cell in the center of the carcinoma. Intense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates can occur in non-medullary infiltrating duct carcinomas; however, when plasma cells predominate, the tumor is more likely to be a medullary carcinoma. A few neutrophils, eosinophils, and monocytes can be found, especially when there is necrosis or cystic degeneration, but never do they dominate in a medullary carcinoma. Rarely, the lymphocytic infiltrate gives rise to germinal centers within the tumor or the surrounding tissue (Figs. 15.11, 15.14 and 15.15). Hence, the presence of germinal centers cannot be relied upon as evidence that one is dealing with metastatic carcinoma in a lymph node in the breast or in the axilla.

Microscopic Circumscription

Noninvasive microscopic circumscription refers to the appearance of the border of the infiltrating carcinoma rather than the periphery of the surrounding lymphoplasmacytic reaction. In medullary carcinoma, the edge of the tumor should have a smooth, rounded contour that appears

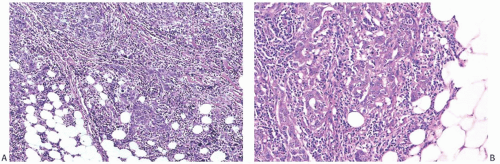

to push aside the breast parenchyma and fat rather than to infiltrate it (Figs. 15.16 and 15.17). Consequently, nonneoplastic glandular or fatty breast tissue should not be found within the main body of the invasive portion of the tumor. In assessing this feature, it is important to distinguish between ducts, lobules, or islands of fat cells trapped in the surrounding lymphoplasmacytic reaction of medullary carcinoma and the same structures invaded by non-medullary invasive carcinoma (Fig. 15.18). In the latter instance, the tumor typically lacks the cohesive syncytial structure of medullary carcinoma, and the tumor cells tend to invade in trabecular, dendritic, or dispersed patterns.

to push aside the breast parenchyma and fat rather than to infiltrate it (Figs. 15.16 and 15.17). Consequently, nonneoplastic glandular or fatty breast tissue should not be found within the main body of the invasive portion of the tumor. In assessing this feature, it is important to distinguish between ducts, lobules, or islands of fat cells trapped in the surrounding lymphoplasmacytic reaction of medullary carcinoma and the same structures invaded by non-medullary invasive carcinoma (Fig. 15.18). In the latter instance, the tumor typically lacks the cohesive syncytial structure of medullary carcinoma, and the tumor cells tend to invade in trabecular, dendritic, or dispersed patterns.

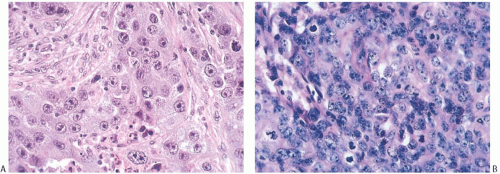

Syncytial Structure

Syncytial structure requires that most of the tumor growth (variously defined as 75% or more of the histologically sampled areas) be arranged in broad irregular sheets or islands in which the borders of individual cells are indistinct (Fig. 15.19). The histology sometimes resembles a poorly differentiated epidermoid carcinoma (Fig. 15.20). This comparison is particularly apt because traces of epidermoid differentiation are not unusual in medullary carcinomas, and some of these tumors have well-formed foci of squamous metaplasia. A tumor that is otherwise characteristic may be accepted as a medullary carcinoma if it has minor components of trabecular, glandular, alveolar, or papillary growth (Fig. 15.21). Such regions may have a diminished lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and fibrosis and thus appear distinct from the medullary growth pattern. It has been reported that overall survival (OS) and relapse-free survival (RFS) are directly related to the extent of the syncytial component.53 Although there was not a significant difference in outcome between patients with 75% and 90% syncytial growth, survival was diminished when less than 75% of a tumor was syncytial, and the difference was most marked at or below the 50% level. These data justify the currently employed requirement for at least a 75% syncytial component.

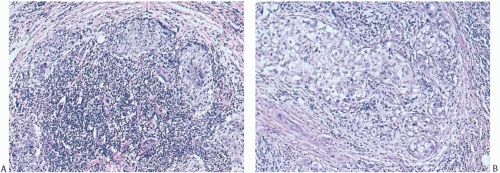

FIG. 15.13. Medullary carcinoma, lobular lymphocytic reaction. A,B: Lymphocytic reaction in lobules at the periphery of a medullary carcinoma. No carcinoma is evident. |

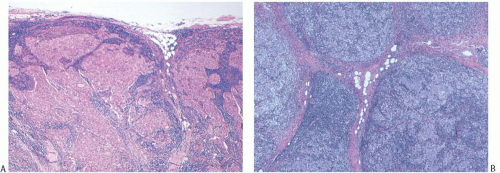

FIG. 15.18. Medullary carcinoma, tumor border. A,B: Fibrofatty stroma is trapped between the tumor nodules, but each nodule has a sharply circumscribed border. |

Nuclear Grade and Mitoses

Poorly differentiated nuclear grade and high mitotic rate are interrelated characteristics of medullary carcinoma. Typically, the tumor cells have pleomorphic nuclei with coarse chromatin and prominent nucleoli (Fig. 15.22). Pyknotic nuclei of degenerating cells are easily found, as are mitotic figures (Fig. 15.23). Regarding the latter, Richardson13 observed that “… seldom are there less than four per high power field, and abnormal forms are common.”

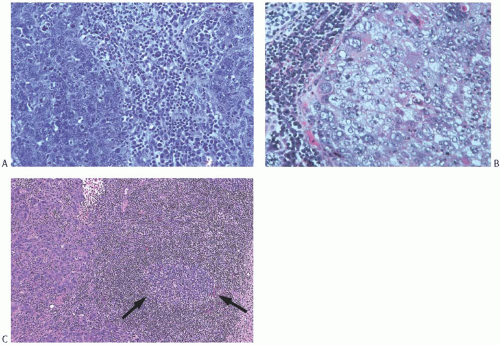

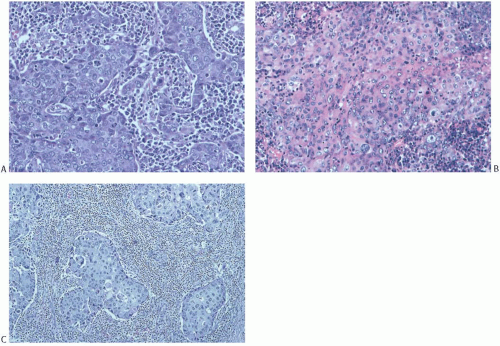

FIG. 15.20. Medullary carcinoma, syncytial growth. A: The carcinoma is distributed in sharply defined bands separated by stroma permeated predominantly by plasma cells. The cytoplasmic borders of individual carcinoma cells are not seen. B: Diffuse cytoplasmic eosinophilia that hints at squamous differentiation (see Fig. 15.26A). C: Islands of syncytial carcinoma cells surrounded by lymphocytes. |

FIG. 15.21. Medullary carcinoma, glandular differentiation. Isolated foci of glandular differentiation such as this may be found in medullary carcinoma. |

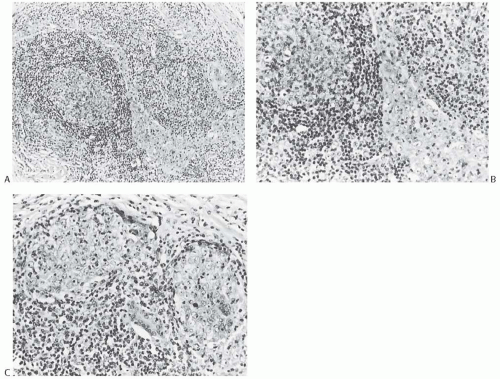

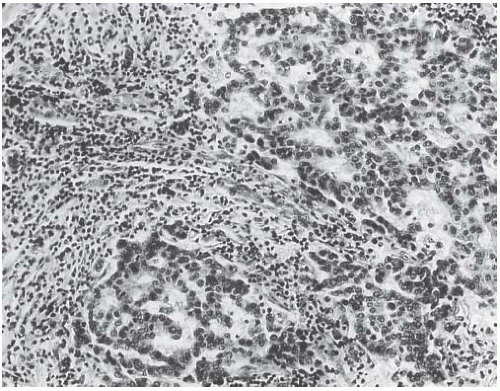

FIG. 15.22. Medullary carcinoma, poorly differentiated nuclear grade. This carcinoma has mitotic figures and pleomorphic nuclei with nucleoli. |

FIG. 15.23. Medullary carcinoma, poorly differentiated nuclear grade. A: Prominent nucleoli. B: Multiple nucleoli and numerous mitoses. |

A number of other microscopic features may be found in some medullary carcinomas. The presence of one or more of these secondary histopathologic characteristics is helpful to confirm a diagnosis of medullary carcinoma, but the diagnosis does not depend on the presence of any of them. These ancillary microscopic features include in situ carcinoma, squamous metaplasia, pseudosarcomatous metaplasia, and necrosis.

Ductal Carcinoma In Situ

Ductal carcinoma in situ

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree