Chapter Sixteen

Medication Misadventures II: Medication and Patient Safety

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to

• Define and compare the terms medication errors, adverse drug events, and adverse drug reactions.

• Describe methods to identify medication errors and adverse drug events.

• Discuss the role of Patient Safety Organizations (PSOs) in health care.

• Assign an event severity rating to reported errors and events.

• Discuss two methods of analyzing medication errors and adverse drug events that are utilized to develop action plans for prevention of recurrence.

• Describe examples of skill-based, rule-based, and knowledge-based errors.

• Explain a systems, approach to error.

• Compare a Just Culture with a culture of shame and blame.

• Determine strategies health care practitioners and health systems can implement to reduce medication errors.

• Reflect on the need for interprofessional education and training on quality and safety principles.

![]()

Key Concepts

Introduction

Much attention has been focused on adverse outcomes in health care in the past 15 years. While pockets of research in medical errors were developing prior to 2000, the Institute of Medicine’s report, To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System,1 released in late 1999, served as a catalyst for additional research in the causes and methods to prevent adverse outcomes in health care. The mortality estimates documented in this report (an estimated 44,000 to 98,000 people die each year as a result of medical errors) were derived from two landmark studies.1–3 The report notes that medication errors alone (whether occurring within or outside of the hospital) were estimated to account for over 7000 deaths annually. The majority of literature to date has focused on work in the hospital setting, as it is, for the most part, a closed and controlled environment. Other settings are less well researched, although early studies of nursing homes and ambulatory settings have shown significant opportunities for improvement. It is clear that medication safety, and the broader category of patient safety, represents a serious concern for patients and health care providers.

While many health care professionals have roles in the medication use process, which is described in depth in Chapter 24, pharmacists play a pivotal role in ensuring the safe use of medication. Pharmacist provision of accurate drug information and identification of potential medication-related adverse effects to multiple providers is of vital importance. Throughout the medication use process there are many opportunities for unexpected adverse events, including errors in prescribing, dispensing, and administering medications, idiosyncratic reactions, and other adverse effects. These events can all be described as medication misadventures.4 All pharmacists need a sound understanding of the risks for error and the ability to identify the underlying causes of medication misadventures, as other practitioners tend to focus on other potential causes. Pharmacists are also responsible for taking steps to prevent such occurrences and minimize adverse outcomes. This usually involves collaborative work with other health care team members to ensure optimal outcomes. Pharmacists are well positioned to lead these efforts in reducing harm to patients.

Definitions: Medication Errors, Adverse Drug Events, and Adverse Drug Reactions

![]() The terms medication error, adverse drug event, and adverse drug reaction are similar and often confused. They are interrelated, yet distinct occurrences. The terminology surrounding medication misadventures is often confusing; there are many definitions that are very similar. The term medication misadventure is an overarching term that includes medication errors, adverse drug events (ADEs), and adverse drug reactions (ADRs). The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists4–5 (ASHP) defines a medication misadventure as an iatrogenic hazard or incident:

The terms medication error, adverse drug event, and adverse drug reaction are similar and often confused. They are interrelated, yet distinct occurrences. The terminology surrounding medication misadventures is often confusing; there are many definitions that are very similar. The term medication misadventure is an overarching term that includes medication errors, adverse drug events (ADEs), and adverse drug reactions (ADRs). The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists4–5 (ASHP) defines a medication misadventure as an iatrogenic hazard or incident:

• That is an inherent risk when medication therapy is indicated

• That is created through either omission or commission by the administration of a medicine or medicines during which a patient may be harmed, with effects ranging from mild discomfort to fatality

• Whose outcome may or may not be independent of the preexisting pathology or disease process

• That may be attributable to error (human or system, or both), immunologic response, or idiosyncratic response

• That is always unexpected or undesirable to the patient and the health professional

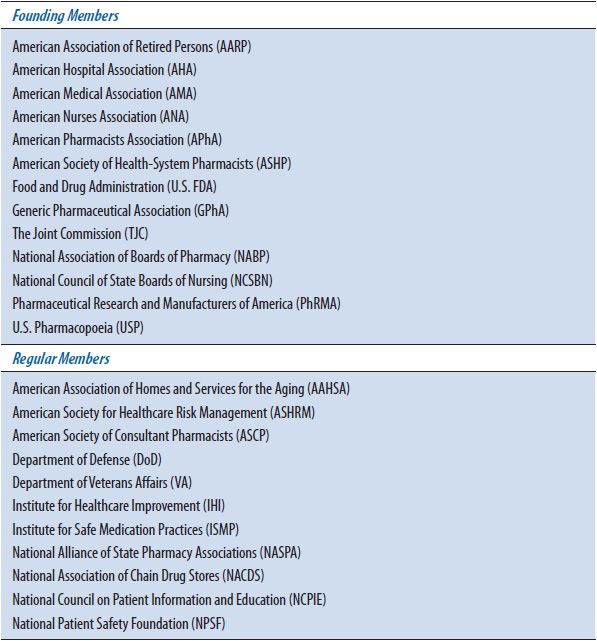

The National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCCMERP), an organization composed of 24 national organizations and individual members, including the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), American Medical Association (AMA), American Pharmacists Association (APhA), United States Pharmacopoeia (USP), and several others (Table 16–1), has developed a detailed definition of what constitutes a medication error:

“Any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is in the control of the health care professional, patient, or consumer. Such events may be related to professional practice, health care products, procedures, and systems, including prescribing; order communication; product labeling, packaging, and nomenclature; compounding; dispensing; distribution; administration; education; monitoring; and use.”6

Key points related to medication errors include:

• Medication errors are preventable.

• Medication errors can be caused by errors in the planning (deciding what to do—which drug and/or what dose) or execution stages (completing the task that was decided on—administering the drug to the wrong patient).

• Medication errors include errors of omission (missed dose or appropriate medication not prescribed) or commission (wrong drug given).

• Medication errors may or may not cause patient harm.

TABLE 16–1. NATIONAL COORDINATING COUNCIL FOR MEDICATION ERROR REPORTING AND PREVENTION MEMBER ORGANIZATIONS

Based on the NCCMERP definition, an error may occur as a result of not adequately counseling or educating a patient on proper use of medication. When, for example, a patient inappropriately uses a metered-dose inhaler for asthma and fails to receive the full amount of the medication, a medication error has occurred. The error may be secondary to a lack of education or may have occurred despite adequate counseling and education. Independent of the cause, based on the above definition, a medication error did occur.

Based on this definition, medication errors also occur when a prescriber writes an incorrect dose on a prescription pad. Even if the prescriber is called by a practitioner to clarify and change the order and the patient eventually receives an appropriately dosed medication, an error did occur in the process. An adverse outcome does not necessarily have to occur to classify an event as a medication error.

An ADE involves harm to a patient. An ADE is defined as an injury from a medicine or lack of intended medicine.7 An ADE refers to all ADRs, including allergic or idiosyncratic reactions, as well as medication errors that result in harm to a patient. It is estimated that 3% to 5% of medication errors result in harm to a patient and can also be classified as an ADE.

An ADR is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “any response that is noxious, unintended, or undesired, which occurs at doses normally used in humans for prophylaxis, diagnosis, therapy of disease, or modification of physiological function.”8

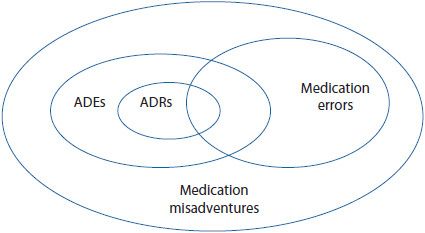

The relationship between the terms is illustrated in Figure 16–1 (also see Chapter 15). While there are standard definitions for medication errors, there may be significant differences in the interpretation, reporting rates, and severity ranking between institutions. Common questions that arise are included in Table 16–2. For example, one institution may determine that an error has occurred when a dose is not received by a patient within 30 minutes of the scheduled time, where another may permit 60 minutes before or after the scheduled administration time. Some institutions may not report an inappropriately written prescription, if that error is caught by a clinician before the medication reaches the patient. Instead, a pharmacist or nurse may report it as a professional intervention. According to most definitions, this would count as an error. These variations make it very difficult to compare data from one institution to another. Therefore, it is best for an institution to use its own data to monitor improvement.

Figure 16–1. Relationship among medication misadventures, adverse drug events, medication errors, and adverse drug reactions. (Adapted from Bates DW, et al. Relationship between medication and errors and adverse drug events. J Gen Intern Med. 1995 Apr;10(4):199-205.)

TABLE 16–2. COMMON QUESTIONS THAT ARISE IN DEFINING MEDICATION ERRORS AND ADVERSE DRUG EVENTS

The Impact of Errors on Patients and Health Care Systems

Patients depend on health care systems and health care professionals to help them stay healthy. As a result, patients frequently receive drug therapy with the notion that these medications will help them lead a healthier life. The initiation of drug therapy is the most common medical treatment received by patients.9 In virtually all cases, patients and their health care providers understand that when medications are given, there are some known and some unknown risks. Patients may experience significant unexpected drug-related morbidity and mortality.

Several landmark studies have identified the risk of medication errors and ADEs in varying populations and settings. The Harvard Medical Practice Study I was a landmark study that estimated that 3.7% of hospitalized patients experience adverse events.2 The findings and extrapolated statistics from this study along with the Harvard Medical Practice Study II served as the grounds for the statement (from To Err Is Human) that approximately 44,000 to 98,000 people are killed by medical error every year. Specifically related to medication errors, Bates and associates identified 6.5 ADEs per hospital admission.7 In the nursing home setting, Gurwitz and associates10 identified 227 ADEs per 1000 resident years. Gurwitz and associates11 also studied the ambulatory patient population, finding 50.1 ADEs per 1000 person-years. Interestingly, preventability of all ADEs in these studies ranged from 27% to 51%, while the preventability of serious and life-threatening ADEs ranged from 42% to 72%, potentially indicating that improved processes and behaviors should be able to prevent serious harm events.

The economic impact of medication errors and ADEs is staggering and adds unnecessarily to the health care cost burden. Several important studies documented the economic burden of these events.12–15 A landmark study in 1995 estimated that ADE-related costs were $76.6 billion annually in ambulatory patients alone.12 Drug expenditures in ambulatory patients at that time were $80 billion per year. This means that for every $1 spent for a drug, almost $1 was also being spent due to a drug-related problem. These costs exceed the total cost of managing patients with diabetes or cardiovascular diseases.13 A subsequent study demonstrated the cost of drug-related morbidity and mortality in the ambulatory setting exceeded $177 billion in 2000.15

While it was initially thought that medication misadventures were caused by individual health care practitioners, including pharmacists, physicians, and nurses, now it is clear that our health care systems and processes often are causative or contributing factors in the majority of errors and events. Efforts to decrease adverse outcomes will not be successful if these system and process-related issues are not addressed. Multiple agencies and professional organizations across the country are now contributing efforts to minimize these events (Table 16–3), which will be discussed in the section Best Practices for Error Prevention.

TABLE 16–3. ORGANIZATIONS INVOLVED IN PREVENTING ADVERSE DRUG EVENTS

Identification and Reporting of Medication Errors and Adverse Drug Events

![]() Several methods of identifying errors are recommended to gain a more global understanding of the risks and errors occurring within an institution. It is important that a systematic approach to the identification and assessment of errors and adverse events be utilized in order to identify trends and opportunities for improvement based on events occurring at a location. This should involve several methods, and include prospective and retrospective methods of identifying errors and risks when possible. Many methods of identifying errors in health care exist, including voluntary reporting, direct observation, chart review, trigger identification, and computerized monitoring. These methods are described further here.

Several methods of identifying errors are recommended to gain a more global understanding of the risks and errors occurring within an institution. It is important that a systematic approach to the identification and assessment of errors and adverse events be utilized in order to identify trends and opportunities for improvement based on events occurring at a location. This should involve several methods, and include prospective and retrospective methods of identifying errors and risks when possible. Many methods of identifying errors in health care exist, including voluntary reporting, direct observation, chart review, trigger identification, and computerized monitoring. These methods are described further here.

1. A voluntary reporting system (either paper, telephonic, or online) is the most common method of identification of errors and events. Many institutions include an anonymous option for those who do not feel comfortable providing their name and contact information. Anyone detecting or committing an error can report it without associating their name with the error. It is essentially risk free for the reporter and, therefore, it may increase the likelihood of having an error reported. While voluntary reporting is the least labor intensive method, it only identifies approximately one out of 20 errors when compared to other identification methods.16 Therefore, it is important to include other methods of detection.

2. The direct observation method uses trained observers to watch the real-time delivery of medications. Notes from the observations are compared with physician’s orders to determine if an error has occurred. Results with this method are more valid and reliable than with self-reporting, but the impact of the observer on the subject being observed and interobserver agreement has been questioned.17,18 This method is costly, time consuming, and limited to the identification of errors that occur during the administration phase of the medication use process. It typically samples a selected time period on a selected unit, limiting the extrapolation to other time periods or patient care areas. On the positive side, errors are often identified that may never be discovered though other methods as they may go unrecognized.

3. Chart review identification of medication errors and ADEs is very labor intensive and is not generally practical outside of the research environment. Various trained staff review charts looking for particular cues or data elements that signify an error or event has occurred. This method relies on practitioners to document these events when identified, which may lead to an underestimation of the true occurrence.

4. A modified version of manual chart review is the use of the ADE trigger tool. It is a tool that is promoted by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI). It is an augmented chart review method that uses automated systems to identify alerts or triggers that have been shown to efficiently identify patients with potential ADEs.19–27 The triggers are cues that a patient may have experienced an error and/or adverse event. Example triggers include the use of reversal agents (e.g., flumazenil, naloxone, phytonadione) or abnormal lab values such as partial thromboplastin time (PTT), international normalized ratio (INR), or low blood glucose value. When these triggers are identified, it is suspected that the patient may have experienced a medication error. The patient’s chart is reviewed for evidence of error and/or level of harm and data is collected and collated to determine potential common causes. For example, reviewing the charts of patients who experience hypoglycemia may reveal errors, such as incorrect insulin dosing while patients are receiving nothing by mouth in preparation for a surgical procedure. Upon review of patients requiring the use of naloxone, it may be discovered that the dosing for hydromorphone and morphine are often confused during the prescribing, administration, and monitoring phases, leading to oversedation. The advantage to using this trigger method is that these types of events are rarely reported as errors. These tools have been used in several ways—as a long-term trend and measure of ADEs and/or in a more focused scope such as triggers related to known high-risk classes of medications.28–30 Specific information on the use of this tool is available at http://www.ihi.org.

5. Classen20,21 and Jha19 developed methods to identify ADEs using an electronic medical record (EMR) with text searching tools and logic-based computer rules. In Classen’s model, the text within the computer charting (e.g., lab, nurses notes, physician progress notes and orders) is searched for defined conditions or cues, such as heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). When identified, a pharmacist is alerted, reviews the patient record, and relays an appropriate recommendation to the prescribing physician. This serves as a real-time intervention to prevent or mitigate harm to the patient. This seems to be an optimal model, allowing concurrent review of potential harm and intervention to prevent further error or harm. Unfortunately, while more organizations are implementing an electronic medical record, many are not capable of searching text or have not yet implemented this option.

The use of technology has presented new sources of data on potential errors. The increased use of automated distribution machines, smart pumps, computerized physician order entry (CPOE), and bar-coding technology provides rich databases. For example, every keystroke a nurse makes in programming a smart infusion pump is recorded. Once an error is identified, it is possible to download the data and review details about the error. The challenge is sorting through the massive volumes of information to derive common themes and strategies to decrease risk and optimize the technology.

The 1999 IOM report spotlighted a serious need to capture data that would help to reduce harm to patients. Congress subsequently passed The Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Act of 2005 (Patient Safety Act). The act authorized the creation of a nationwide network of Patient Safety Organizations (PSOs) to improve safety and quality through the collection and analysis of data on patient events.31 The act provides a venue for institutions to report information related to errors and events with the goal of collating the information and learning the underlying risks across similar types of events.

The act provides confidentiality and privilege protection to organizations. The fear of legal action related to reported event information has prevented many organizations from voluntarily reporting errors and events to external agencies. The confidentiality protections ensure that information about an error that is provided to the authorized PSO is kept confidential. The privilege protections limit or forbid the use of protected information in criminal, civil, and other proceedings. Specifically, the information will not be subject to subpoena, discovery, or disclosure to any federal, state, or local criminal, civil, or administrative proceeding. The information may not be used in a professional disciplinary hearing, nor be admitted as evidence.

One example, the Pennsylvania Patient Safety Reporting System, has been collating error data since 2004 and publishes regular advisories with the goal of improving health care delivery systems and educating providers about safe practices. For example, in December 2009,32 the advisory reviewed errors with neuromuscular blocking agents. In a 5-year span, 154 reports related to neuromuscular blocking agents were submitted. The advisory provides specific information related to the contributing factors (unsafe storage, look-alike drug names, similar packaging, and unlabeled syringes) that increase the risk for a fatal error. Specific risk-reduction strategies are outlined. The same errors tend to recur in facilities across the United States (U.S.). Recall the heparin errors in premature infants33 that have occurred at least three times in different states. It is imperative that health care professionals commit to learn from others and critically self-assess the processes within their own institution to ensure their process is as safe as possible. Being a learning organization is essential to prevent errors within an organization. A learning organization is one in which the leadership supports organizational learning, creating an environment where structured processes are developed to support this. Examples include communication of performance data to the staff level, formal training in performance improvement and problem solving at the unit or department level, and active engagement of staff in local problem solving. It is recommended that hospitals, ambulatory centers, and other organizations join a PSO and commit to forwarding data related to adverse outcomes, enabling the collation of larger quantities of data, which the PSO can analyze and use to provide recommendations to member organizations. This enables local and broad scale learning from errors and events.

Classification of Error Types

![]() Classification of errors by type is a common method to identify common themes and causes of events. The most common way to classify errors is to identify them by type of error. For medications, this classification focuses on whether an error was related to dispensing, administering, prescribing, monitoring, or other reasons. There have been many taxonomies of errors developed by various groups, including the World Health Organization, The Joint Commission, MEDMARX®, and others. The ASHP previously designated categories of medication errors are listed here.34 These are similar to those outlined by NCCMERP.

Classification of errors by type is a common method to identify common themes and causes of events. The most common way to classify errors is to identify them by type of error. For medications, this classification focuses on whether an error was related to dispensing, administering, prescribing, monitoring, or other reasons. There have been many taxonomies of errors developed by various groups, including the World Health Organization, The Joint Commission, MEDMARX®, and others. The ASHP previously designated categories of medication errors are listed here.34 These are similar to those outlined by NCCMERP.

• Prescribing error

• Omission error

• Wrong time error

• Unauthorized drug error

• Improper dose error

• Wrong dosage form error

• Wrong drug preparation error

• Wrong administration technique

• Deteriorated drug error

• Monitoring error

• Compliance error

• Other medication error

As a result of the development of PSOs, a common taxonomy and language was required to enable health care providers to collect and submit standardized information related to safety events. These standard event reporting forms are called the Common Formats. The Common Formats define the standardized data elements associated with errors and events that are to be collected and reported to the PSO. The scope of Common Formats applies to all patient safety concerns including events reaching the patient (with or without harm), near-miss events that do not reach the patient, and unsafe conditions that have the potential to cause an error or event.35 The Common Formats recently updated (V1.2) by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) are likely to become the standard for reporting. Common Formats for Readmission and Skilled Nursing facilities are currently open for comment. The following event types have been defined for medication errors:

• Incorrect patient—An incorrect patient error occurs when a medication is given to the wrong patient, usually caused by an error in patient identification and confirmation. Two identifiers should be used to identify the patient every time a patient is given a medication. Confirming patient identification is necessary whenever a pharmacist or physician writes or enters an order or dispenses a prescription in outpatient areas.

• Incorrect medication—This error occurs when a medication is administered that was not ordered for the patient. This may occur when a patient receives a medication intended for another patient, due to inadequate patient identification, or when a nurse obtains the incorrect medication for administration, perhaps from floor stock. Barcode scanning is designed to prevent these errors and others.

• Incorrect dose (subcategories of overdose, underdose, omitted dose, extra dose, and unknown)—An incorrect dose error can occur when a prescriber orders an inappropriate dose of a medication or when the dose administered is different than what was prescribed. An omission error occurs when a patient does not receive a scheduled dose of medication. This is considered to be the second most common error in the medication use process.36

• Incorrect route of administration (subcategories include the intended route and the actual route). Some of the most harmful incorrect route errors have included administration of enteral tube feeding into an intravenous line or instillation of an IV medication intrathecally that is not designed to be given this route. One significant cause is the fact that these varying types of tubing fit together. Appropriate design includes different types of connectors of tubing that would not physically allow a connection to be successful.

• Incorrect timing (too early, too late, unknown)—What constitutes a wrong time error may vary considerably among organizations. In general, this type of error occurs when a dose is not administered in accordance with a predetermined administration interval. Most organizations realize that it is often impossible to be totally accurate with the administration interval and typically allow 15 to 60 minutes outside that interval. Establishing a policy to indicate what constitutes an error in this category is needed for consistent reporting and data collection.

• Incorrect rate (too fast, too slow, unknown)—This category generally applies to intravenous infusions, but can also apply to an intravenous push medication if the drug is pushed too quickly or too slowly.

• Incorrect duration—The patient receives the medication for a shorter or longer time period than prescribed. For example, a patient is prescribed a one-time dose of a medication. The pharmacist must enter the order as daily so it will show up on the medication administration record (MAR) for the nurse to administer and chart; however, he or she must remember to place “one time” in the correct field so it only appears to the nurse once to administer. If the pharmacist forgets that last step (relying on memory is a poor error prevention strategy), the medication will appear on the MAR for daily administration.

• Incorrect dosage form (e.g., extended release instead of immediate release)—A wrong dosage form error can occur when the prescriber makes an error or when a patient receives a dosage form different from that prescribed, assuming the appropriate dosage form was originally ordered.

• Incorrect strength or concentration—This is an error that can occur at several points in the medication use process, from prescribing to administration. The pharmacist may choose the wrong strength when entering the order, a pharmacy technician may select the wrong drug for dispensing, or a nurse may choose the wrong drug upon administration. The appropriate use of barcode administration of medications in the inpatient setting makes it harder to make these errors.

• Incorrect preparation (e.g., splitting tablets, compounding errors)—When medications require some type of preparation, such as reconstitution, this type of error may occur. These kinds of errors may also occur in the compounding of various intravenous admixtures and other products and can occur when nurses, pharmacists, or technicians are preparing medications.

• Expired or deteriorated product—This error occurs when a drug is administered that has expired or has deteriorated prematurely due to improper storage conditions.

• Medication that is a known allergen to the patient. These errors may occur due to lack of adequate interfaces between different computer or technology software programs.

• Medication known to be contraindicated for the patient such as a drug–drug interaction or drug–food interaction.

• Incorrect patient action (patient taking a dietary supplement that interacted with medication, whether or not he or she was told to avoid taking it)—This type of error occurs when patients use medications inappropriately. Proper patient education and follow-up may play a significant role in minimizing this type of error. This type of error may be a direct result of insufficient patient counseling from a pharmacist, a prescriber, or both. Important components in counseling include consideration of the level of health literacy of the patient and methods to gauge their understanding of their medication regimen and information provided. An adequate learning needs assessment may assist in effective counseling based on an individual patient’s needs.

The second classification section of the medication Common Formats report asks at what stage the incorrect action was discovered (regardless of where or when the incorrect action originated) with the following choices:

• Purchasing

• Storing

• Prescribing

• Transcribing

• Preparing

• Dispensing

• Administering to patient (including verifying medication)

• Monitoring

Prescribing errors generally focus on inappropriate drug selection, dose, dosage form, or route of administration. Examples may include ordering duplicate therapies for a single indication, prescribing a dose that is too high or too low for a patient based on age or organ function, writing a prescription illegibly, prescribing an inappropriate dosage interval, or ordering a drug to which the patient is allergic.

In one study, the most common type of prescribing error (56.1%) was related to an inappropriate dose (either too high or too low). The second most common prescribing error was related to prescribing an agent to which the patient was allergic (14.4%). Prescribing inappropriate dosage forms was the third most common error (11.2%).9 Other relatively common prescribing errors have included failing to monitor for side effects and serum drug levels, prescribing an inappropriate medication for a particular indication, and inappropriate duration of therapy.

Monitoring errors occur when patients are not monitored appropriately either before or after they have received a drug. For example, if a patient is placed on warfarin therapy and adequate blood tests (baseline and ongoing) are not performed to assess the patient’s response, a monitoring error has occurred and has the potential to result in a life-threatening hemorrhage. The Joint Commission recognized this as a significant safety risk and developed a National Patient Safety Goal in an effort to encourage organizations to improve and standardize this process.

These types of medication errors are not mutually exclusive. Multiple types of errors may occur during a single administration of a drug and a single adverse patient outcome may be the result of more than one type of error.34

Additional information is gathered in the PSO reporting process. As the use of Common Formats grows, individual health care organizations will need to adopt these classifications, likely developing a standard taxonomy over time. Visit the PSO Web site for updated versions of the Common Formats at https://www.psoppc.org/web/patientsafety/commonformats

Classifying Patient Outcomes

Although the classification of errors or events frequently is based on type, most are also classified by the patient outcome related to the error or event. When an error occurs, there is not always an adverse outcome. It has been estimated that 3% to 5% of errors result in harm to patients. It is important for institutions to monitor both the types of errors that occur and the outcomes associated with them. Most reporting systems request information regarding type and outcome of a medication error.

The NCCMERP developed a medication error index that serves to categorize errors based on the severity or outcome of the error. This index is divided into four main categories and nine subcategories as follows37: See the index for event classification and corresponding algorithm at http://www.nccmerp.org/medErrorCatIndex.html

1. No error

• Category A: Circumstances or events that have the capacity to cause error.

2. Error, no harm

• Category B: An error occurred, but the medication did not reach the patient.

• Category C: An error occurred that reached the patient, but did not cause the patient harm.

• Category D: An error occurred that resulted in the need for increased patient monitoring, but caused no patient harm.

3. Error, harm

• Category E: An error occurred that resulted in the need for treatment or intervention and caused temporary patient harm.

• Category F: An error occurred that resulted in initial or prolonged hospitalization and caused temporary patient harm.

• Category G: An error occurred that resulted in permanent patient harm.

• Category H: An error occurred that resulted in a near-death event (e.g., anaphylaxis and cardiac arrest).

4. Error, death

• Category I: An error occurred resulting in patient death.

Oftentimes, the initial staff member(s) reporting the error has an opportunity to indicate their interpretation of the level of harm to the patient. In follow-up, a medication safety pharmacist and the unit/department manager may investigate further details and assign a final severity classification based on the ultimate outcome to the patient.

Institutions may use information about outcomes to focus their error prevention efforts on the types of errors resulting in the most serious outcomes. It is important to remember that examining near-miss events (those that do not reach the patient) can be as valuable in preventing future errors as focusing on serious outcomes. These near-miss events are often clues to the underlying process issues that require attention before they cause harm to a patient.

National Reporting

Reporting of medication errors is important for every practitioner without regard to their practice setting. However, institutional internal reporting is often emphasized (above external reporting) because it is necessary in order to maintain the institution’s accreditation status. Drug information specialists are in an ideal position to encourage the importance of medication error and ADR reporting to all health professionals, especially when they are consulted to answer questions related to potential cases. In an effort to share institutional experiences and avoid the same errors being repeated at several institutions, national reporting systems for institutions have evolved.

• MedWatch—This program was developed by the FDA Medical Products Reporting Program for the purpose of monitoring problems with medical products. MedWatch monitors quality, performance, and safety of medical products, devices, and medications. This program contributes to surveillance of medication errors that may be associated with product labeling and names.38 MedWatch collects reports about faulty products (e.g., improperly functioning devices that led to a medication error). Significant reports may result in distribution of e-mail and safety alerts to health care professionals. These announcements can also be viewed on the Internet at http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/default.htm. Health care professionals and consumers can report ADEs and product problems by completing a MedWatch 3500 form (found on the Web site) and mailing it to the FDA, by calling 1-800-FDA-1088, or reporting online at http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/HowToReport/ucm085568.htm

• ISMP Medication Errors Reporting Program (MERP)—This program provides a venue for voluntary medication error reporting to the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP). Reports can be submitted online at http://www.ismp.org/reporterrors.asp. ISMP is a federally certified Patient Safety Organization which collates errors and provides summary information across multiple cases in an effort to identify risk and support prevention strategies.

• MEDMARX®—This program is an anonymous, subscription-based, voluntary reporting system that enables facilities to collect and report medication error, ADE, and ADR data. This service allows subscribing organizations to report and monitor organization-specific errors online, as well as compares their error rates with other subscribing organizations of similar type. Each year the USP compiles the data, summarizes it, and presents an in-depth annual report. Information in the report includes types of medication errors, causes, contributing factors, products involved, and actions taken. More information regarding MEDMARX® can be found at http://www.usp.org/products/medMarx/. This product differs from the ISMP MERP program in that it is a fee-based service that enables comparison data within the database.

Managing an Event Reporting System

The Joint Commission and ASHP standards can be used as a basis for starting an error-reporting program. In addition to the standards, the pharmacy and medical literature contain abundant examples of successful programs. The following steps are a compilation of several of these references:

1. Develop definitions and classifications for errors and events that work for the institution. The definitions and classifications in the literature and this chapter provide a good starting point for discussion. It is anticipated that the Common Formats developed in preparation for external reporting to PSOs will eventually become the standard.

2. Assign responsibility for the program within the pharmacy and throughout other key departments. A multidisciplinary approach is an essential factor. The program needs a leader and an advocate. It also needs the involvement of nursing, physicians, quality, and risk management departments in order to function as a collaborative team to work toward improved processes.

3. Develop forms or online methods for data collection and reporting (see #1 above). Other mechanisms for reporting (hotline phone numbers) may be used as well. Electronic reporting can often be designed such that medication errors are reviewed by a medication safety pharmacist to confirm severity of the event and gather additional information as needed in order to determine whether additional analysis is appropriate. These systems can also forward events based on their severity to other appropriate parties within the institution such as risk management, quality, and safety personnel to ensure awareness of key staff and leaders. This serves as the voluntary reporting component of the program.

4. Promote awareness of the program and the importance of reporting errors and adverse events. Provide feedback to reporters and individual units that discuss their errors as well as those of others, along with steps taken to prevent them. Providing feedback is very important to ensure that those reporting feel that the identified errors are reviewed and methods to prevent recurrence are developed and implemented.

5. Develop policies and procedures for determining which errors, events, and ADRs are reported to the FDA. The responsibility for this reporting should be defined and usually resides with someone in the pharmacy department.

6. Establish mechanisms for regular screening and identification of potential medication errors and ADEs to supplement voluntary reporting. These mechanisms should include retrospective reviews, concurrent monitoring, as well as prospective planning for high-risk groups. It is worthwhile to educate clinicians to check for potential events or reactions when they see orders for certain triggers that are often used to treat an error or event (Table 16–4), orders to discontinue or hold drugs, and orders to decrease the dose or frequency of a drug.19 Additionally, electronic screening methods to check for laboratory tests that are indicative of potential events (e.g., drug levels, Clostridium difficile toxin assays, elevated serum potassium, and low white blood cell counts) can be helpful.21

7. Routinely review medication errors, ADEs, and ADRs for trends. Report all findings to the pharmacy and therapeutics committee and other hospital or organization quality and safety committees. It is beneficial to present facility specific data, nationally reported errors of significance, as well as incorporate storytelling into various presentations. Oftentimes, telling a story that engages one’s emotions, followed by your own data specific to the event, reinvigorates the efforts to work toward safer processes.

8.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree