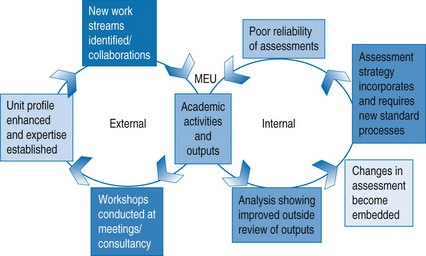

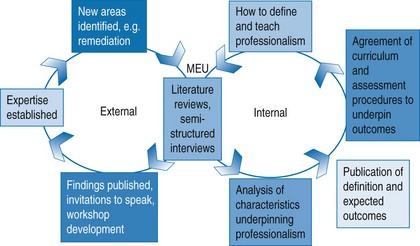

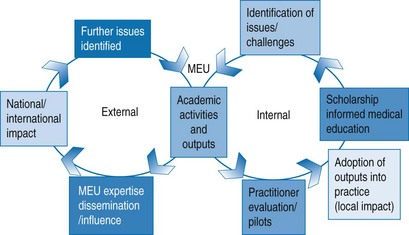

Chapter 49 It has been said that in the past the practice of medicine was simple, safe and largely ineffective; today it is much more effective but complex, and potentially dangerous. More than ever, then, medical education needs to prepare and support students and doctors in their roles as providers of safe healthcare. Within the UK the amount of time spent as a trainee has changed dramatically within the last decade. Streamlining of medical training and the implementation of the European Working Time Directive has meant that education and training will need to be delivered differently, and knowledge and skills cannot be expected to osmose into trainees merely from them spending time within that discipline. Not only have major changes occurred during the trainee years but modern consultants and senior GPs are different too. There is recognition that mastery of a medical specialty is impossible and that the key to high-quality patient care is nested within continuous professional development and adopting an attitude of lifelong learning. All these changes have meant that medical education has achieved a new prominence and importance, and following the development of evidenced-based clinical practice it is becoming increasingly accepted that medical education should be evidence-based rather than founded on pragmatism, fashion and whim (Todres et al 2007). The Leeds Institute for Medical Education (LIME) has developed a useful representation of this idea of scholarship (Fig. 49.1) (Kilminster & Roberts 2010, personal communication). Other colleagues, such as those at the Karolinska Institute in Finland, have independently developed similar concepts. The LIME model consists of two circles of activity. The ‘internal’ circle relates to work generated and undertaken in the educators’ own institution for the benefit of its staff, students and trainees. The ‘external’ circle relates to activities undertaken outside the educators’ institution such as disseminating good practice developed as part of their ‘internal’ circle work or undertaken in response to external issues or challenges. Fig. 49.1 The LIME (Leeds Institute of Medical Education) scholarship model (Kilminster & Roberts 2010, personal communication). Accurate assessment of competence is fundamental to any medical education programme. Some years ago at one of our institutions concern was expressed about the reliability of the final assessments (identification of issues). Members of the medical education unit (MEU) undertook an analysis of these issues and reviewed the literature and examined theories of assessment to identify best practice (academic activities). The result of these activities was the use of item response theory to analyse question performance, the production of a number of workshops to address areas such as question, OSCE station construction, examiner and simulated patient training (outputs). These workshops were piloted, evaluated and, where appropriate, adopted into mainstream practice (local impact) and formed a very obvious example of scholarship-informed local medical education practice. Continued evaluation and further identification of new issues feed the continuation of the internal circle. These activities also fed into external work (Fig. 49.2). It has become increasingly obvious that teaching, learning and assessment of the development of medical professionalism are as important as the development of medical knowledge and skills. Many of the referrals to regulatory bodies are related to medical professionalism issues. Work by Papadakis and colleagues (2008) has shown that doctors who were reported to state licensing bodies in the United States had often had professionalism issues when in medical school when their records were examined (identification of issues). Improving the curricula in this area involved a series of academic activities. An initial literature search was undertaken to identify a definition of professionalism together with characteristics identified with the term professionalism. A separate literature search was undertaken to investigate methods of assessment of professionalism. Within the institution a series of semi-structured interviews were undertaken with a range of healthcare professionals and undergraduate students to identify characteristics associated with the individuals who would be considered excellent role models for professionalism. Using the results of the literature reviews and empirical research, a curriculum and associated assessment programme was devised, piloted (evaluation), refined and subsequently adopted (outputs; Fig. 49.3).

Medical education research

Introduction

The internal circle

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree