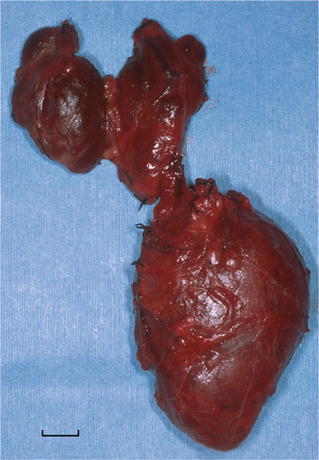

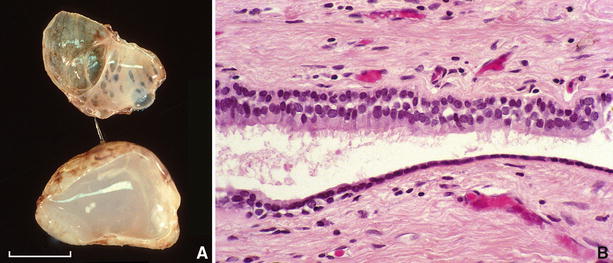

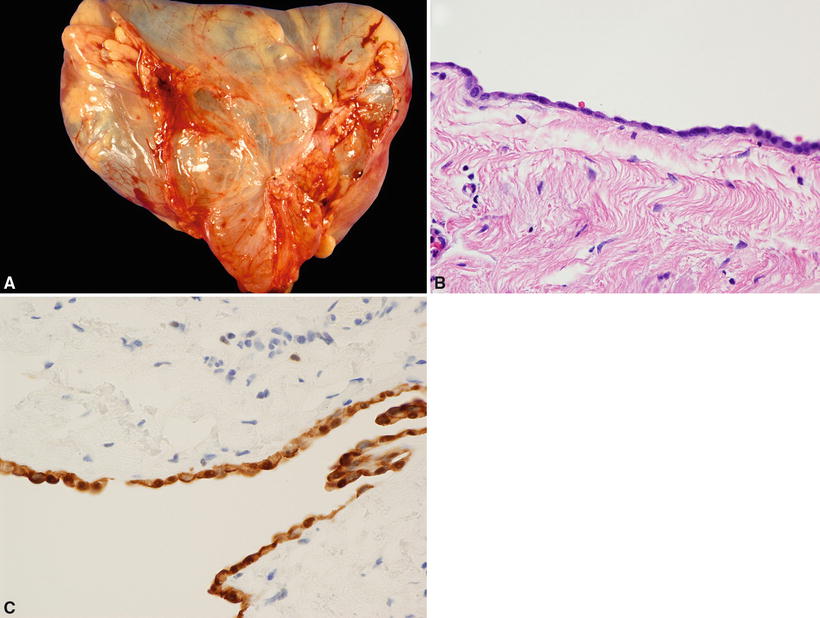

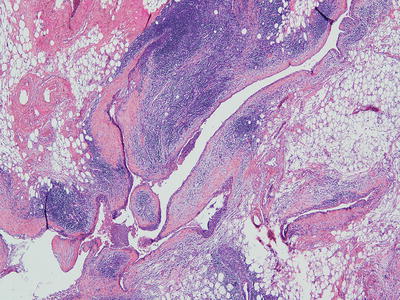

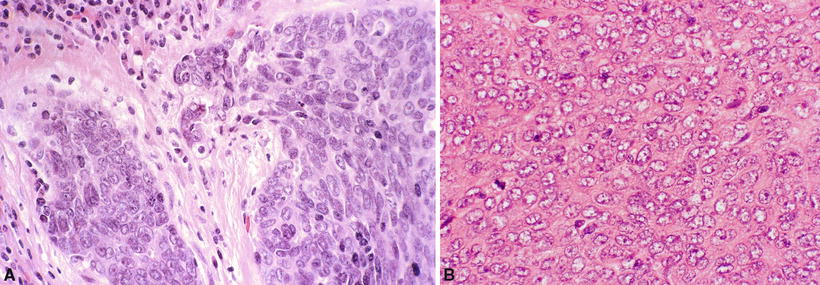

Fig. 26.1.

(A) Mediastinal granuloma . Enlarged, matted lymph nodes replaced by fibrocaseous granulomas (scale = 1 cm). (B) Fibrocaseous granuloma with central cavitation within lymph node. (C) Budding yeast-like organisms consistent with Histoplasma capsulatum (GMS stain).

Microscopic

♦

Lymph node architecture is partially or completely effaced by necrotizing granulomatous inflammation, fibrosis, and calcified caseonecrotic debris. The histological pattern is similar in both fungal and mycobacterial infections (Fig. 26.1B)

♦

Organisms may be visualized by acid fast stains for mycobacteria or Gomori methenamine silver for yeast forms of Histoplasma capsulatum (Fig. 26.1C)

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Mycobacterial vs. fungal infection

The histopathological features are similar as discussed above. Organisms may be demonstrated by acid fast or fungal stains

♦

Sarcoidosis

In sarcoidosis, mediastinal lymph nodes are enlarged by nonnecrotizing granulomas. Stains for microorganisms are negative, and granulomas are confined within the capsule of the lymph node

♦

Infected teratoma or bronchogenic cyst

Necrosis may obscure typical identifying features of teratoma or bronchogenic cyst simulating the appearance of a fibrotic cavitated mass of lymph nodes

♦

Fibrosing mediastinitis

Fibrosing mediastinitis (see below) is a more generalized process within the mediastinum, extending well beyond infected lymph nodes. Caseous necrosis is usually absent. The major histological feature is coarse, ropy, sparsely cellular collagen. Obstruction of major mediastinal structures such as the superior vena cava is commonly present

Fibrosing Mediastinitis

Clinical

♦

Fibrosing mediastinitis is a form of chronic mediastinitis characterized by compressive and obstructive involvement of mediastinal structures. The presenting manifestation is often that of an asymptomatic mediastinal mass. There is a predominance of young adult females

♦

A variety of compression syndromes include:

Superior vena cava syndrome

Tracheobronchial compression (hilar fibrosis)

Pulmonary artery or venous obstruction

♦

Mediastinal fibrosis may be associated with collagen vascular disease, pseudotumor of orbit, Riedel struma, retroperitoneal fibrosis, and pulmonary hyalinizing granuloma. An association with elevated IgG4 levels has also been described

The etiology of fibrosing mediastinitis is unknown; however, an exaggerated response to histoplasma infection is thought to be involved in many, if not most, cases in the United States

Macroscopic

♦

Macroscopically a firm, gray, ill-defined mass of fibrous tissue invades and compresses mediastinal structures

Microscopic

♦

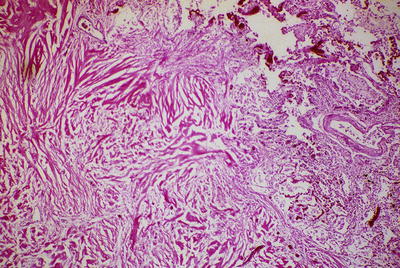

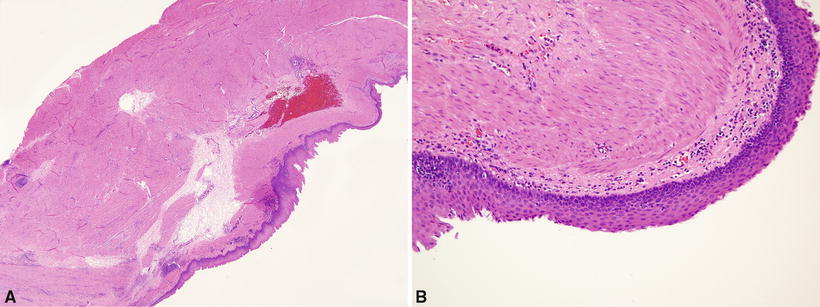

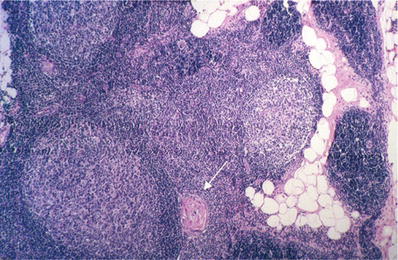

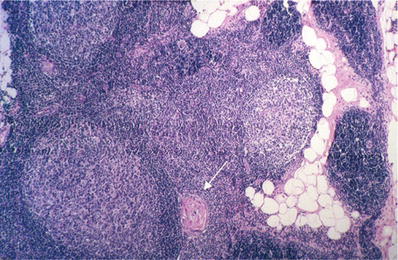

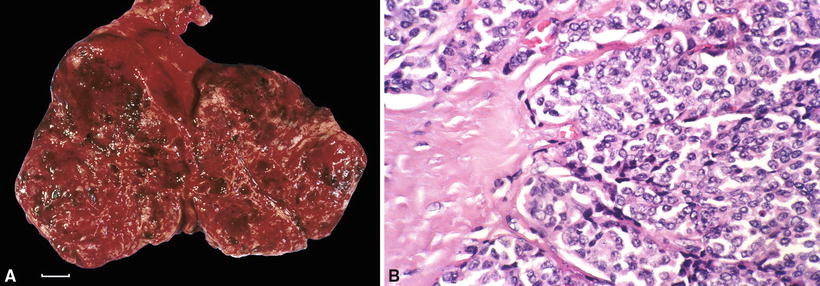

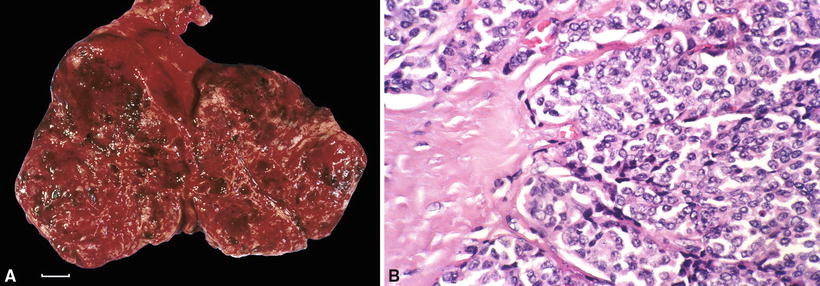

Histologically fibrosing mediastinitis is characterized by dense paucicellular hyalinized collagenous tissue (ropy collagen) (Fig. 26.2), with scant lymphocytic and plasmacytic inflammation. Fibromyxoid granulation tissue may represent an early stage of the process. Rare granulomas, if present, may suggest an infectious etiology

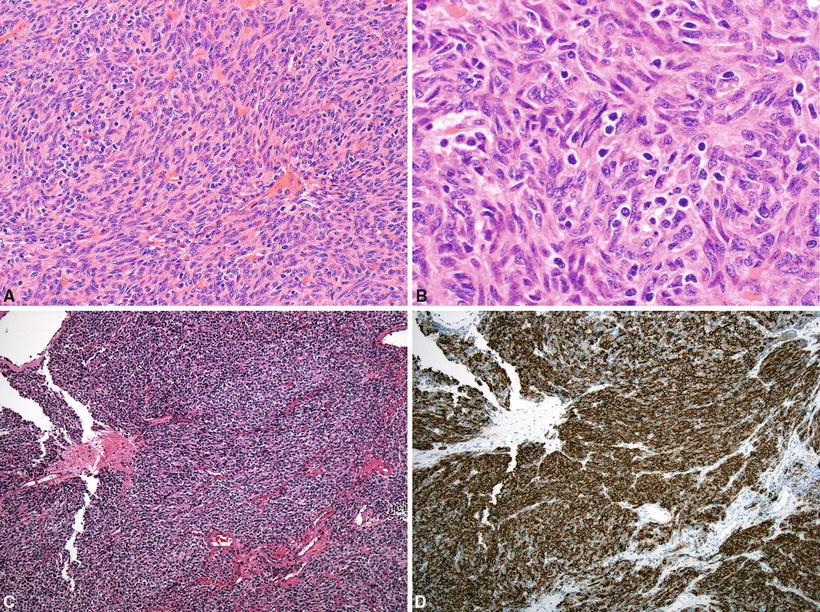

Fig. 26.2.

Fibrosing mediastinitis . Dense, ropy, collagenous fibrosis infiltrates the adjacent lung tissue (right and upper).

♦

Secondary effects seen in open lung biopsy include hyalinizing granulomas or are the result of central pulmonary vein occlusion including pulmonary hemosiderosis, venous infarcts, and venous and arterial sclerosis which can simulate pulmonary venoocclusive disease or pulmonary venous hypertension

Immunohistochemistry

♦

CD45, CD3, vimentin, or muscle actins are nonspecific markers of lymphocytes or mesenchymal cells in early cellular lesions. There are few reactive cells in sclerotic lesions

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Nodular sclerosis Hodgkin disease; other lymphomas with sclerosis

Reed-Sternberg cells in Hodgkin disease are positive for CD30 and CD15. Sclerosing lymphomas of the mediastinum are often of B-cell type (see section on “Lymphoproliferative Disorders”)

♦

Fungal/mycobacterial infection (granulomatous mediastinitis)

Histoplasmosis is the most common cause of granulomatous mediastinitis, although mycobacteria are sometimes responsible. Histologically fibrocaseous granulomas form a localized mass (see “Granulomatous Mediastinitis”)

♦

Amyloidosis

Amyloidosis is more amorphous than the ropey collagen of fibrosing mediastinitis. Stains for amyloid include Congo red with apple-green birefringence on polarization or metachromasia with crystal violet stain

♦

Progressive massive fibrosis (PMF )

PMF refers to large conglomerate masses due to the inhalation of coal dust and/or silica. PMF usually resides within the lung parenchyma although lesions may extend to mediastinal structures. Coarse collagen may have a whorled appearance especially when silica exposure has occurred. Abundant black pigment and birefringent crystals consistent with silica and silicates appear throughout the lesion

♦

Desmoplastic mesothelioma (rare)

Desmoplastic mesothelioma is a variant of sarcomatous mesothelioma in which coarse paucicellular collagen is a major histological feature. Mesothelioma may extend from the pleura or pericardium into the mediastinum. Pleomorphic sarcomatoid tumor cells which stain positively for keratin suggest the diagnosis of desmoplastic mesothelioma

Cystic Lesions

Bronchogenic Cyst

Clinical

♦

Bronchogenic cyst , the most common congenital cyst of the mediastinum, is derived from the embryonic foregut and occurs mainly in children and young adults. Symptoms occur when the cyst becomes infected or compresses bronchi. The usual location is the middle mediastinum

Macroscopic

♦

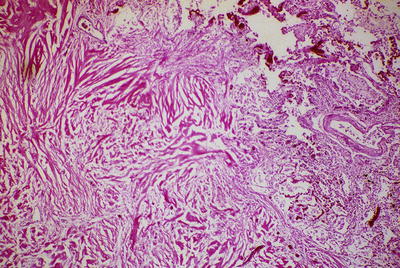

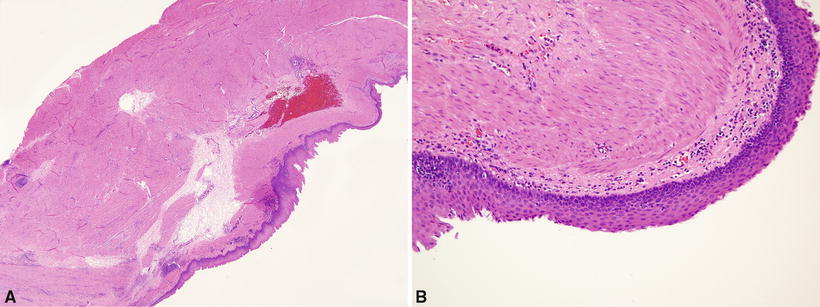

The gross appearance is that of a smooth, thin-walled spherical, unilocular or multilocular, and clear or gelatinous fluid-filled cyst (Fig. 26.3A)

Fig. 26.3.

(A) Bisected bronchogenic cyst showing inner trabeculations of cyst wall and mucoid content (scale = 1 cm). (B) Epithelial lining of bronchogenic cyst consists of ciliated respiratory epithelium.

Microscopic

♦

Respiratory or squamous epithelium forms the inner lining which overlays a wall in which the bronchial glands, smooth muscle, and cartilage may be present (Fig. 26.3B)

Immunohistochemistry

♦

The epithelium of bronchogenic cyst stains positively for CK7 and TTF1

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Esophageal cyst

The esophageal cyst usually occurs on the right side. Histologically it is lined by squamous epithelium and has a wall structure devoid of the cartilage with a prominent double muscle layer

♦

Metastatic teratoma

Metastatic testicular teratoma may occur in the mediastinum. The distinction from bronchogenic cyst includes better differentiated architecture in bronchogenic cyst with predominantly respiratory-type epithelium that is positive for CK7 and TTF1. Metastatic teratoma has mixed enteric and respiratory-type epithelium and variably stains positively for CK20, CDX-2, CK7, and TTF1, respectively

Esophageal Cyst

Clinical

♦

Esophageal duplication cyst is most frequently seen in infancy and early childhood. The cyst closely approximates the wall of the esophagus in the middle or posterior mediastinum. Symptoms of respiratory distress occur due to compression of bronchopulmonary structures

Macroscopic

♦

The gross appearance is that of a smooth-walled spherical, unilocular fluid-filled cyst

Microscopic

♦

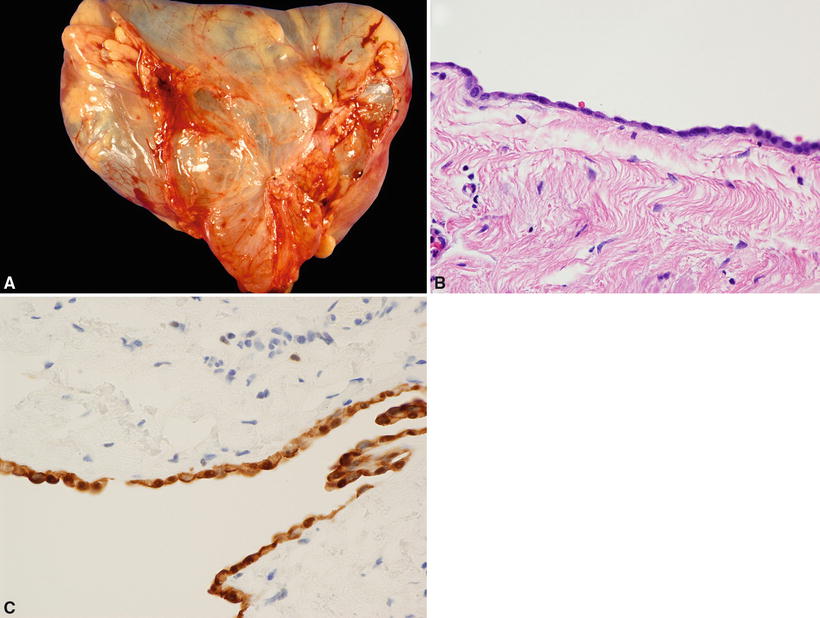

Histologically the inner lining consists of squamous and/or ciliated epithelium or columnar epithelium (Fig. 26.4A)

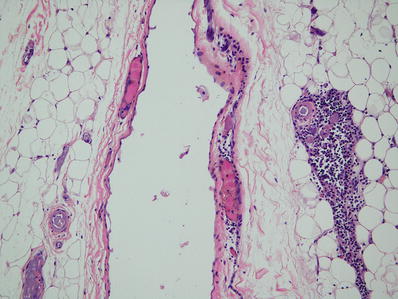

Fig. 26.4.

(A) Esophageal duplication cyst . Thick double-layered smooth muscle. Cyst wall devoid of cartilage. (B) Squamous epithelium lines surface of cyst.

♦

Esophageal glands may be present, but the cartilage is absent. The most definitive feature is a double layer of the smooth muscle in the wall (Fig. 26.4B)

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Bronchogenic cyst

The cartilage is often present in the wall and there is no double muscular layer. Bronchogenic cysts may occur in the wall of the esophagus

Gastroenteric Cyst

Clinical

♦

Gastroenteric cyst is most frequently seen in infancy and early childhood. The cyst is usually located in the posterior mediastinum and is frequently connected to the vertebral column. Symptoms occur due to compression of bronchopulmonary structures or to nerve compression, peptic ulceration, or perforation

♦

Gastroenteric cysts are often associated with malformations of thoracic vertebrae (neurenteric cyst)

Macroscopic

♦

The gross appearance is that of a unilocular cyst attached to the vertebral column or within the esophageal wall

Microscopic

♦

The inner lining is variable: gastric, duodenal, small intestinal, large intestinal, squamous, or respiratory epithelium (or mixed epithelium). Occasionally pancreatic tissue is present. There is usually a well-developed muscularis propria

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Gastroenteric cysts are differentiated from bronchogenic cysts by the absence of the cartilage and the presence of the columnar epithelium. The distinction from esophageal cyst is by location and the presence of gastric or intestinal epithelium

Pericardial Cyst (Coelomic Cyst)

Clinical

♦

Pericardial cysts usually occur in adulthood and have a typical location in the right cardiophrenic angle, often an asymptomatic finding on chest X-ray. However, large cysts may cause hemodynamic compromise

Macroscopic

♦

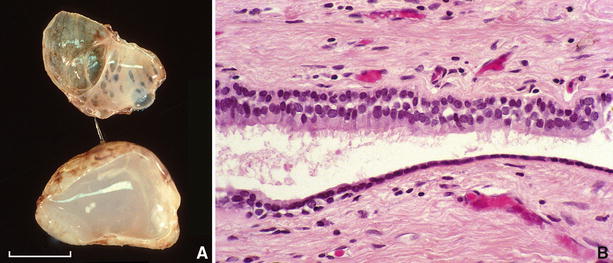

The gross appearance is that of a roughly spherical, unilocular, and thin-walled cyst filled with serous fluid (Fig. 26.5A). There is usually no communication with the pericardial sac

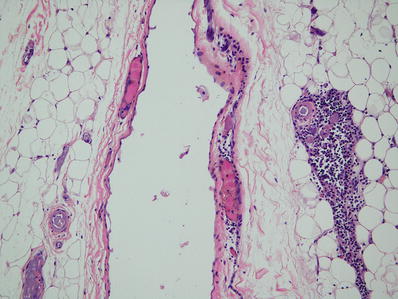

Fig. 26.5.

(A) Pericardial (coelomic) cyst . (B) Cyst lined by flattened mesothelial cells. (C) Cyst-lining cells show nuclear and cytoplasmic staining for calretinin.

Microscopic

♦

The inner lining is composed of a single layer of mesothelial cells overlying loose connective tissue (Fig. 26.5B)

Immunohistochemistry

Differential Diagnosis

♦

See “Bronchogenic Cyst,” “Esophageal Cyst,” and “Gastroenteric Cyst”

♦

Thymic cyst

Thymic cyst is located in the superior mediastinum, and there is thymic tissue in its wall

Unilocular Thymic Cyst (Developmental Origin)

Clinical

♦

Unilocular thymic cyst is of developmental origin. It is a small cyst located more often in the lateral neck than in the (anterosuperior) mediastinum

Macroscopic

♦

The gross appearance is that of a unilocular cyst with a thin, translucent wall

Microscopic

♦

The histological appearance shows flat, cuboidal, columnar, or (rarely) squamous epithelial lining of the inner cyst wall. Usually there is a lack of inflammation and thymic tissue is present in the cyst wall (Fig. 26.6)

Fig. 26.6.

Unilocular thymic cyst . Thin-walled cyst lined by flat epithelium. Thymic remnant adjacent to cyst. Incidental finding at autopsy.

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Pericardial cyst

Pericardial cyst is located at the cardiophrenic angles and lacks thymic tissue in its wall

Multilocular Thymic Cyst (Acquired [Reactive] Process)

Clinical

♦

Multilocular thymic cyst is regarded as an acquired, reactive lesion that clinically presents most frequently as an asymptomatic large tumorlike mass in the anterosuperior mediastinum

♦

It is usually an incidental finding on chest X-ray

♦

It is frequently associated with thymic neoplasms, such as germ cell tumors, lymphoma, thymoma, or thymic carcinoma

♦

Multilocular thymic cyst may arise in setting of HIV infection

Macroscopic

♦

The macroscopic appearance is that of a multiloculated cyst with thick fibrous septa forming compartments that contain cloudy to blood-tinged fluid

♦

Large cysts may be densely adherent to adjacent mediastinal structures, simulating a neoplasm

Microscopic

♦

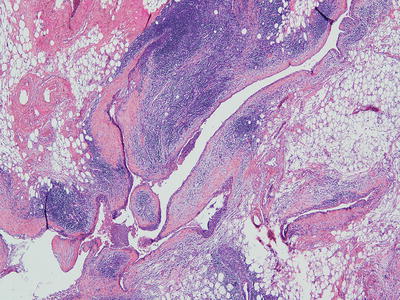

The lining epithelium of the cysts is usually squamous; however, flat cuboidal or ciliated columnar cells may occur either as a single layer or as a stratified epithelial lining

♦

Acute and chronic inflammation with fibrovascular proliferation, necrosis, hemorrhage, cholesterol granulomas, and reactive lymphoid hyperplasia is also common (Fig. 26.7)

Fig. 26.7.

Multilocular thymic cyst . Multiloculated cyst with dense chronic inflammation associated with thymoma.

♦

Thymic tissue is present in the cyst wall

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Cystic thymoma

As opposed to multilocular thymic cyst, cystic thymoma maintains features of thymoma with nodular proliferation of thymic epithelial cells in addition to prominent cystic changes

Cystic teratoma (see “Germ Cell Tumors”)

♦

Cystic lymphangioma

Prominent ectatic lymphatic channels are the hallmark of cystic lymphangioma

♦

Nodular sclerosis Hodgkin disease and large cell lymphoma with cystic changes (see “Lymphoproliferative Disorders”)

♦

Seminoma (germinoma) with cystic changes (see “Germ Cell Tumors”)

♦

Thymic carcinoma

Thymic carcinoma can be distinguished from multilocular thymic cyst by its malignant cytology showing invasive growth

Nonneoplastic Lesions of Thymus

Thymic Dysplasia

Clinical

♦

Thymic dysplasia is a condition present at birth, thought to represent failure or arrest in thymic development

♦

Thymic dysplasia is associated with various immunodeficiency syndromes, including usual X-linked or autosomal recessive form of severe combined immunodeficiency, ataxia telangiectasia, and related chromosomal instability syndromes, Nezelof syndrome, and incomplete form of DiGeorge syndrome (the thymus is usually located ectopically in DiGeorge syndrome)

Macroscopic

♦

The thymus is of very small size (<5 g)

Microscopic

♦

The histological features include primitive-appearing epithelium without segregation into cortical and medullary regions

♦

Absence of Hassall corpuscles

♦

Almost total absence of lymphocytes

♦

Small-sized vessels

Differential Diagnosis

♦

The major differential diagnosis of thymic dysplasia is acute thymic involution, often seen at autopsy. The discriminating features of acute thymic involution are:

Acute thymic involution results from stress and superimposed infections

There is marked lymphocytic depletion with preservation of lobular architecture and of Hassall corpuscles

Vessels are disproportionately large compared to the size of lobules

Inflammatory cells (particularly plasma cells) are scattered within interlobular and perilobular tissue

Thymic Aplasia

Clinical

♦

Thymic aplasia refers to the complete absence of the thymus

♦

Thymic aplasia is present from birth and is most notably associated with the complete form of DiGeorge syndrome

Macroscopic and Microscopic

♦

There is a complete absence of the thymus gland, accompanied by parathyroid developmental failures in DiGeorge syndrome

True Thymic Hyperplasia

Clinical

♦

True thymic hyperplasia refers to the enlargement of the thymus gland (by weight and volume) beyond upper limit of normal for age

♦

Seen mainly in children, the clinical significance of true thymic hyperplasia is unknown. It may represent an immunologic rebound phenomenon (e.g., post-cessation of chemotherapy) or a sequela of other therapeutic manipulation

Macroscopic

♦

Enlarged thymus gland by weight and volume

Microscopic

♦

Microscopically the thymic architecture is normal

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Thymoma

True thymic hyperplasia is discerned from thymoma by the preservation of thymic architecture in hyperplasia

Lymphoid Hyperplasia (Thymic Follicular Hyperplasia)

Clinical

♦

Lymphoid hyperplasia refers to the increased presence of lymphoid follicles within the thymus gland. Lymphoid hyperplasia is associated with myasthenia gravis (in majority of cases), systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, allergic vasculitis, thyrotoxicosis, and other autoimmune diseases

Macroscopic

♦

The thymus gland is usually of normal size and weight for age

Microscopic

♦

There are an increased number of lymphoid follicles with prominent germinal centers (Fig. 26.8)

Fig. 26.8.

Thymic lymphoid hyperplasia . Prominent lymphoid follicles are present in the thymus gland. Note adjacent Hassall corpuscle (arrow).

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Thymoma

There is preservation of thymic architecture in lymphoid hyperplasia

♦

Reactive lymph node hyperplasia or lymphoproliferative lesions

Reactive germinal centers with preserved thymic architecture distinguish thymic lymphoid hyperplasia from reactive lymph nodes and from lymphoproliferative disorders involving the thymus

♦

Mediastinal seminoma with florid follicular lymphoid hyperplasia

Variant of mediastinal seminoma in which lymphoid follicular hyperplasia may obscure the germ cell tumor

May be underdiagnosed as reactive lymphoid hyperplasia

Lesions Mimicking Primary Mediastinal Neoplasms

Substernal Thyroid (Mediastinal Goiter)

Clinical

♦

Substernal goiter refers to enlarged thyroid due to nodular hyperplasia usually located in the anterior-superior mediastinum. Mediastinal goiter is usually connected to a cervical goiter and receives its blood supply from cervical arteries

♦

The main presentation is an asymptomatic neck mass. Tracheal compression with associated dyspnea is the major complication in about 25% of cases

♦

Radioactive iodine scanning is positive in over 50% of cases

♦

Associated thyroid malignancy ranges from 2 to 20%

♦

Anterior substernal goiter can usually be excised via a neck incision

Macroscopic

Microscopic

♦

The histopathology is that of typical nodular thyroid hyperplasia as seen in cervical adenomatous goiter (see Chapter 20)

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Other mediastinal thyroid lesions such as adenoma or carcinoma are much less frequent

Mediastinal Parathyroid Lesions

Clinical

♦

Parathyroid lesions arise from ectopic parathyroid tissue in the superior mediastinum

♦

Clinically parathyroid adenomas and hyperplasia are associated with hyperparathyroidism and hypercalcemia

♦

Mediastinal parathyroid lesions may assume a larger size than cervical lesions

Macroscopic

♦

The macroscopic appearance is that of an enlarged parathyroid gland. Parathyroid cysts are rare

Microscopic

♦

Parathyroid cyst is a simple cyst with parathyroid tissue in its wall

Differential Diagnosis

♦

The major differential considerations in the mediastinum are paraganglioma or thymic carcinoid tumor

Neither of these lesions is associated with hypercalcemia

Histologically chief cells and/or water clear cells indicate parathyroid lesions. Sustentacular cells are seen in paragangliomas

Other Conditions

Pneumomediastinum

Clinical

♦

Pneumomediastinum refers to air within the fascial planes of the mediastinum, often in association with pulmonary interstitial emphysema, pneumopericardium, pneumothorax, and subcutaneous emphysema

♦

The major causes of pneumomediastinum are mechanical ventilation (barotrauma), esophageal perforation, acute mediastinitis, and increased intrathoracic pressure (e.g., straining, Valsalva maneuver)

♦

Chest X-ray and CT scan show mediastinal air outlining the aorta, esophagus, and left heart border

Macroscopic

♦

Grossly, air bubbles and crepitance in mediastinal tissue are seen at autopsy

♦

Associated tension pneumothorax is often also seen in patients receiving mechanical ventilation

Microscopic

♦

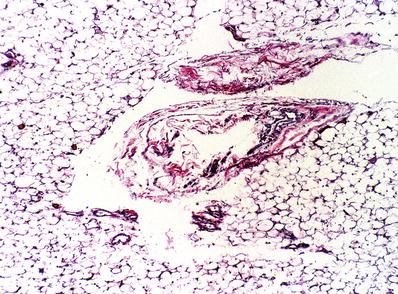

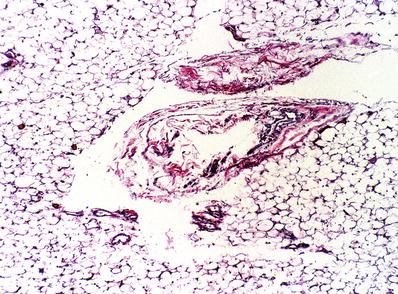

The microscopic appearance is that of widened, empty interstitial spaces in the mediastinal fat (Fig. 26.10)

Fig. 26.10.

Pneumomediastinum . Empty-appearing cystic spaces displace the mediastinal fat and fibrovascular tissue (Elastic van Gieson).

♦

Associated interstitial pulmonary emphysema shows similar widened spaces which track along bronchovascular bundles within the lung

Differential Diagnosis

♦

The major histological differential diagnosis is lymphangiectasia

Lymphangiectasia has the same distribution as interstitial air dissection

Look for endothelial lining in lymphangiectasia vs. acute hemorrhage and empty spaces in air dissection

Neoplasms

Thymus

Histologic Features of Thymus

♦

The thymus is a lobulated and encapsulated organ and is subdivided into cortex and medulla

♦

The different cell types of the thymus include epithelial cells, lymphocytes (traditionally known as thymocytes), and other (minor) cell types

♦

Epithelial cells are endodermally derived cells. They modulate the differentiation of T lymphocytes and are keratin and HLA-DR positive. The different subtypes of epithelial cells include cortical cells that are medium to large, round or polygonal with conspicuous nucleoli, and medullary cells with spindled nuclei and epithelium forming Hassall corpuscles

♦

Lymphocytes (thymocytes) are bone marrow-derived cells. The different subtypes include (a) cortical thymocytes which are immature T cells (cytoplasmic CD3+/surface CD3−, CD1a+, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT)+, and double negative for CD4/8 or coexpressing CD4/8) and (b) medullary thymocytes which are mature T lymphocytes (surface CD3+, either CD4+ or CD8+)

♦

Other (minor) cell types of the thymus are interdigitating reticulum cells, Langerhans cells, mast cells, eosinophils (especially in neonates), and mesenchymal stromal cells

Thymoma

♦

Thymomas are tumors of the thymic epithelium that are cytologically bland and demonstrate the presence of associated cortical-type T cells (cortical thymocytes)

♦

Classification is difficult and has been controversial, and systems have been criticized for poor interobserver reproducibility

♦

Classification systems for thymoma include:

Lattes-Bernatz classification (1961)

Marino and Muller-Hermelink classification (1985)

Suster and Moran classification (1999)

WHO classification (2004 and 2015): most widely used system (Table 26.1)

Table 26.1.

The Definitions of the WHO Classification Categories of Thymic Epithelial Tumors

Type A: A tumor composed of homogeneous population of neoplastic epithelial cells having spindle/oval shape, lacking nuclear atypia, and accompanied by few or no nonneoplastic lymphocytes

Type AB: A tumor in which foci having the features of type A thymoma are admixed with foci rich in lymphocytes; the segregation of the two patterns can be sharp or indistinct

Type B1: A tumor which resembles the normal functional thymus in that it combines large expanses having an appearance practically indistinguishable from the normal thymic cortex with areas resembling thymic medulla

Type B2: A tumor in which the neoplastic epithelial component appears as scattered plump cells with vesicular nuclei and distinct nucleoli among a heavy population of lymphocytes; foci of squamous metaplasia and perivascular spaces are common

Type B3: A tumor predominantly composed of epithelial cells having a round or polygonal shape and exhibiting mild atypia, admixed with a minor component of lymphocytes; foci of squamous metaplasia and perivascular spaces are common

Thymic carcinoma: Primary epithelial tumors of the thymus that show overt cytologic features of malignancy. Morphologically, they look like carcinomas of other organs

The International Thymic Malignancy Interest Group (ITMIG) refined guidelines and definitions to WHO classification, including major and minor criteria, and proposed new type A variant (2014)

Clinical

♦

Thymomas are mainly seen in adults in their fifth, sixth, and seventh decades. They are usually located in the anterosuperior mediastinum. The most common symptoms include dyspnea, chest pain, and cough

♦

On chest X-ray, CT, and MRI, a thymoma appears as a lobulated mediastinal mass

♦

Thymomas can be seen in association with certain diseases:

Myasthenia gravis (mainly associated with type AB, B2, and B3 thymoma)

Hypogammaglobulinemia (mainly associated with type A thymoma)

Red cell aplasia (mainly associated with type A thymoma)

Treatment

♦

Surgery alone can be the treatment for an entirely encapsulated thymoma; however, there is a 2–10% recurrence rate. Surgery with radiation is used for invasive thymomas and chemotherapy is used for metastatic disease

Prognosis

♦

Thymomas are generally indolent. However, all are considered malignant (regardless of histologic subtype)

♦

The degree of tumor invasion (stage of disease) is the most important prognostic factor. WHO histologic subtype may be an independent prognostic factor, particularly in Stage I and II thymomas, among which WHO type A, AB, and B1 thymomas form a low-risk group. All histologic types are capable of invasive growth and metastasis. The proportion of invasive tumors increases by type – from A to AB, B1, B2, and B3. Myasthenia gravis has no prognostic significance

Macroscopic

♦

Circumscribed thymomas can range from 2 to 20 cm in size. They are predominantly solid, white to light brown or yellowish gray, lobulated by connective tissue septa, and encapsulated (Fig. 26.11A). Cystic degeneration and necrosis may be seen in larger tumors. Invasive thymomas are grossly similar to circumscribed thymomas but, in addition, infiltrate surrounding structures

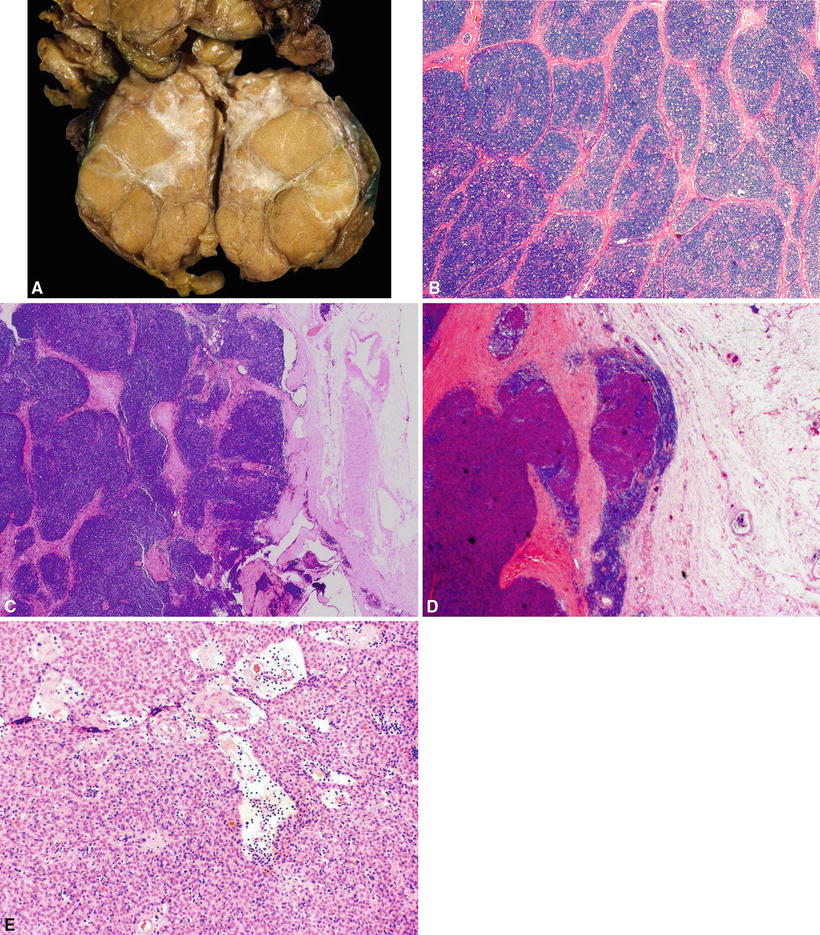

Fig. 26.11.

(A) Circumscribed thymoma (mixed type). Note lobules of tumor separated by bands of connective tissue and central scar. (B) Thymoma , general features. Cellular lobules separated by fibrous septa. (C) Thymoma, general features. Note intact capsule. (D) General features. Invasive thymoma. The thymoma breaks through the capsule and invades the lung parenchyma. (E) Thymoma, general features. Perivascular spaces (serum lakes) containing lymphocytes, proteinaceous fluid, red blood cells, and foamy macrophages.

Microscopic

♦

In general (applies to all histologic subtypes), thymomas show cellular lobules separated by fibrous septa (Fig. 26.11B, C). The fibrous capsule is complete in circumscribed thymomas and incomplete with capsular invasion in invasive thymomas (Fig. 26.11D). Varying proportion of lymphocytes and neoplastic epithelial cells is seen. Perivascular spaces containing lymphocytes, proteinaceous fluid, red blood cells, foamy macrophages, or fibrous tissue are also seen (Fig. 26.11E). Occasional gland or pseudogland structures or Hassall corpuscle-like structures can be present

♦

Type A and AB thymomas have spindled or oval-shaped epithelial cells, while type B thymomas have epithelioid epithelial cells

♦

Type B thymomas are subclassified based on lymphoid cell density, with type B1 having a dense lymphoid component, B2 being intermediate, and B3 having low-absent lymphoid component

♦

Most thymomas demonstrate a mixture of different histologic types

♦

Histologic subtypes (WHO/ITMIG):

Major criteria: required for diagnosis

Minor criteria: supportive/helpful, but not required for diagnosis

♦

Type A (Fig. 26.12A–D):

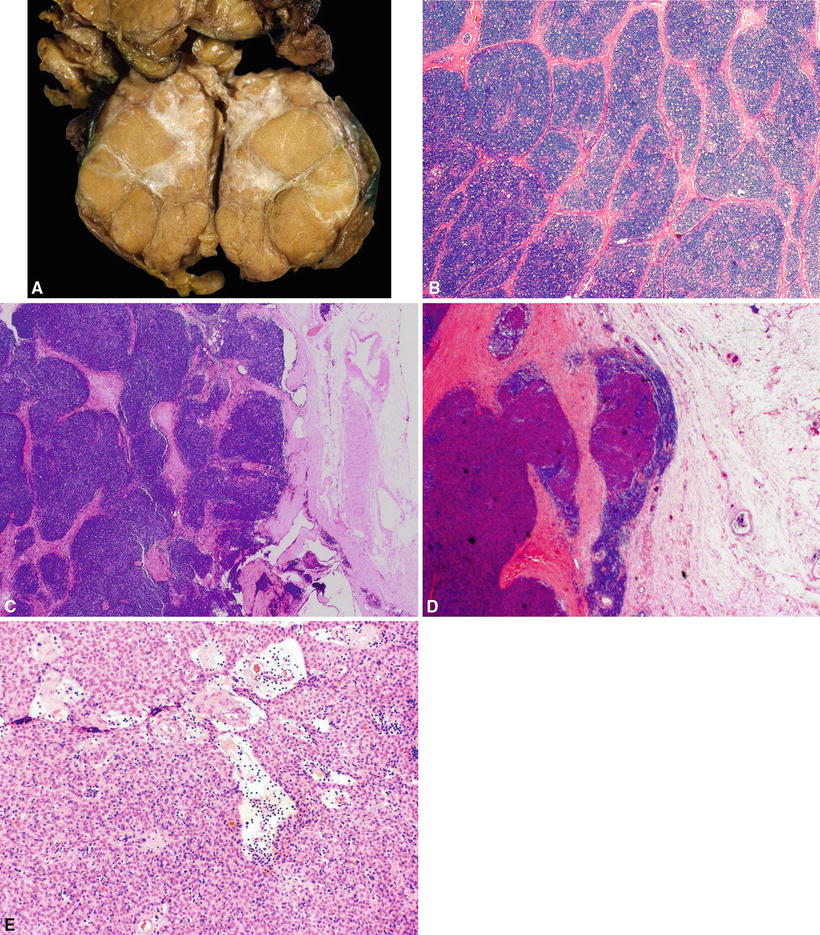

Fig. 26.12.

(A–C) Type A thymoma . (D) Epithelial cells in type A thymoma demonstrating immunoreactivity for CD20.

Predominantly spindle or oval-shaped epithelial cells are present with few or no mature lymphocytes. This type of thymoma can show variable patterns including storiform, hemangiopericytoma-like, rosette-like, and glandular formation. Perivascular spaces are uncommon. Capsular invasion is rare

Major criteria: high epithelial cell content, spindled or oval-shaped tumor cells lacking nuclear atypia, paucity or absence of TdT+ T cells, and absence of medullary islands

Minor criteria: large lobular growth pattern, rosettes, subcapsular cysts, focal glandular formations, pericytomatous vascular pattern, paucity or absence of perivascular spaces (PVS), lack of Hassall corpuscles, complete or major encapsulation, expression of CD20 in epithelial cells (Fig. 26.12D), and absence of cortex-specific markers (beta5t, PRSS16, and cathepsin V)

♦

Atypical type A (new subtype proposed by ITMIG): In addition to the above criteria for type A, also demonstrate increased mitotic activity (four or more mitoses per ten HPF) and coagulative necrosis (tumor necrosis). Necrosis may predict aggressive behavior

♦

Type AB :

Spindled epithelial cells with focal or diffuse abundance of immature lymphocytes. Perivascular spaces are occasionally seen. Capsular invasion is rare

Major criteria: high epithelial cell content, spindled or oval-shaped tumor cells, and moderate to high TdT+ T cells

Minor criteria: biphasic pattern at low magnification (due to variable lymphocyte content), medullary islands rare, small lobular growth pattern rare, usually large lobular growth pattern, paucity or absence of perivascular spaces (PVS), expression of CD20 in epithelial cells, and presence of cortex-specific markers (beta5t, PRSS16, and cathepsin V)

♦

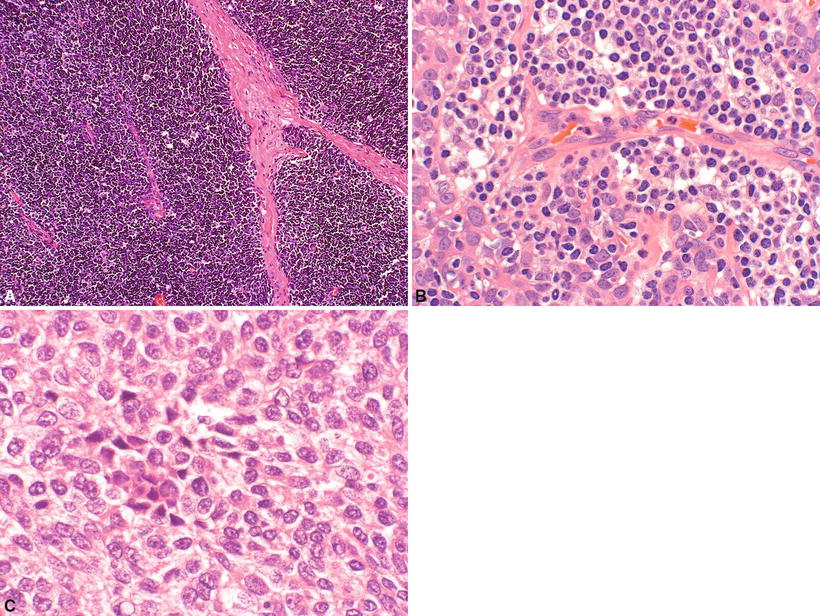

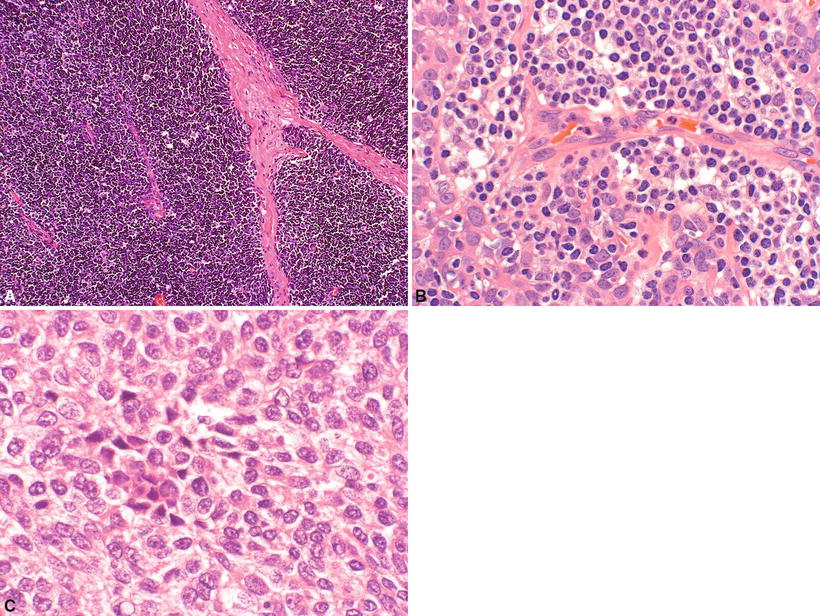

Type B1 (Fig. 26.13A):

Fig. 26.13.

(A) Type B1 thymoma . (B) Type B2 thymoma. (C) Type B3 thymoma.

Closely resembles the normal thymus with cortical areas and medullary islands. Well-formed lobules are seen with intervening sclerotic septa. Scattered large polygonal epithelial cells (keratin+), obscured by a diffuse, small, and round lymphocytic background (CD1a+, TdT+, CD99+, coexpress CD4/8), are present. Medullary islands appear as pale-staining areas with epithelial cells, mature T cells (TdT−), and B cells (CD20+), with or without Hassall corpuscles, surrounded by dark cortical areas. Perivascular spaces are often present. Capsular invasion is rare

Major criteria: thymus-like pattern throughout, medullary islands (+/− Hassall corpuscles), no confluence of epithelial cells in cortical areas (clusters of three or more epithelial cells should not be present), and absence of any type A areas

Minor criteria: large lobular growth pattern is common (small lobular growth pattern is rare), perivascular spaces commonly present, and keratin+ network (as in the normal thymus)

♦

Type B2 (Fig. 26.13B):

Sheets of polygonal epithelial cells (with large nuclei and prominent nucleoli) are intermixed with lymphocytes. Lobulation is often seen. There is minimal medullary differentiation. Capsular invasion may be present

Major criteria: confluence of epithelial cells (at least three adjacent cells) in cortical areas and absence of any type A areas

Minor criteria: thymus-like pattern is rare, medullary islands (+/− Hassall corpuscles) occasionally present, small lobular growth pattern is common (large lobular growth pattern is rare), perivascular spaces commonly present, and keratin+ network (denser than in the normal thymus)

♦

Type B3 (Fig. 26.13C):

Sheets of polygonal epithelial cells with sparse or absent immature lymphocytes. Epithelial cells typically have irregular “raisinoid” nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, and eosinophilic to clear cytoplasm. In other cases, cells may show large vesicular, hyperchromatic granular nuclei and conspicuous nucleoli. Slight to moderate cellular atypia may be present, and mitotic figures (up to 10/10 HPF) can be seen. They usually show an invasive growth pattern

♦

Invasive (malignant) thymomas are defined as thymomas with any of the above histologic subtypes with evidence of invasion (Fig. 26.11D)

♦

Very rare thymoma subtypes include micronodular thymoma, metaplastic thymoma, microscopic thymoma, sclerosing thymoma, and lipofibroadenoma (for more information on these very rare subtypes, refer to the WHO)

Electron Microscopy

♦

Neoplastic epithelial cells show branching tonofilaments, complete desmosomes, elongated cell processes, and basal lamina

Immunohistochemistry (see Table 26.2)

♦

Some commonly used antibodies, including pancytokeratins, p63, CD1a, TdT, CD99, CD20, CD5, and CD117, can be very helpful for thymoma classification (see Table 26.2)

♦

Specific antibodies for thymoma such as AIRE, FoxN1, and CD205 are available but typically only used in the research setting or at referral centers

Table 26.2.

Immunohistochemistry for Thymoma Subtypes and Thymic Carcinoma

A | AB | B1 | B2 | B3 | TC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Background immature T cells (markers CD1a, TdT, CD99) | None to low | Moderate to high # | High # in background, but not in medullary islands | Moderate to high # | None to low # | None |

Pancytokeratin or p63 | + | + | Like the normal thymus; fine network | Denser than the normal thymus; clusters of ≥3 adjacent cells | Even denser than B2 | + |

CD20 | Expressed in epithelial cells | Sometimes expressed in epithelial cells (50%) | Expressed in mature B cells in medullary islands but not in epithelial cells | |||

CD5 | − in epithelial cells, only + in lymphocytes (all thymoma subtypes) | + in both epithelial cells and lymphocytes (thymic carcinoma) | ||||

CD117 | − | − | − | − | − | + |

GLUT1 | − | − | − | − | − | + |

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Thymic carcinoma (in differential with type B2 and B3 thymoma)

Cytologically malignant with high mitotic rate, atypical mitoses, invasive growth, sclerosis in center of tumor, and coagulative necrosis. GLUT-1, c-kit (CD117), and CD5 are positive in thymic carcinoma, but negative in thymoma. Infiltrating lymphocytes are mature lymphocytes and negative for CD1a and TdT (very useful criteria in needle biopsy). Usually thymic carcinomas are not associated with myasthenia gravis

♦

Neuroendocrine tumor and paraganglioma (in differential with type A thymoma)

Unencapsulated; monomorphous cell population with true rosettes, ribbons, or festoons are seen. These tumors show positive staining for neuroendocrine markers

♦

Thymic Hodgkin lymphoma

There is extensive fibrosis with rounded (as opposed to angulated) lobules. Prominent cysts can be seen. Reed-Sternberg cells or lacunar cells (CD15+, CD30+) and mixed inflammatory cells are also seen

♦

Precursor B or T lymphoblastic lymphoma (LBL)

Diffuse growth or thin, separated lobules with numerous mitoses in lymphoid cells. They may be positive for T-cell receptor or immunoglobulin chain gene rearrangement

♦

Primary mediastinal (thymic) large B-cell lymphoma (diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [DLBCL] with sclerosis)

Diffuse growth pattern with variable fibrosis with occasional compartmentalization. Residual cystic thymus can be seen. Lymphocytes have vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and variable cytoplasm. B-cell markers (CD20) are positive

♦

Thymic seminoma

Subdivided by fine fibrous trabeculae into variable-sized compartments. Placental-like alkaline phosphatase (PLAP) and c-kit positive and keratin negative

♦

Localized lymphoid hyperplasia (vs. type B1 thymoma)

Retention of normal cortical and medullary structure and the presence of lymphoid follicles with germinal centers are seen

♦

Fibrous histiocytoma and hemangiopericytoma (vs. type A thymoma with storiform and hemangiopericytoma-like growth pattern)

Keratin negative

♦

Spindle epithelial tumor with thymus-like elements (SETTLE )

Seen at young age with occurrence in the thyroid gland. Mucous glands are frequently present. Lymphocytes are absent

Thymic Carcinoma

Clinical

♦

Thymic carcinomas are rarely associated with myasthenia gravis or other thymoma-related paraneoplastic syndromes. Patients are usually asymptomatic or have nonspecific symptoms found by routine chest X-ray. Occasionally they may present with superior vena cava syndrome. The usual metastatic sites are the lymph nodes (mediastinal, cervical, and axillary), bone, lung, liver, and brain. Treatment is surgery and radiation with or without chemotherapy. Prognosis depends on the histologic subtype. Nonkeratinizing carcinomas (including lymphoepithelioma-like tumors), sarcomatoid carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, and undifferentiated (anaplastic) carcinoma (Fig. 26.14A, B) are very aggressive. Squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) are of intermediate category, and mucoepidermoid and basaloid carcinomas are relatively indolent

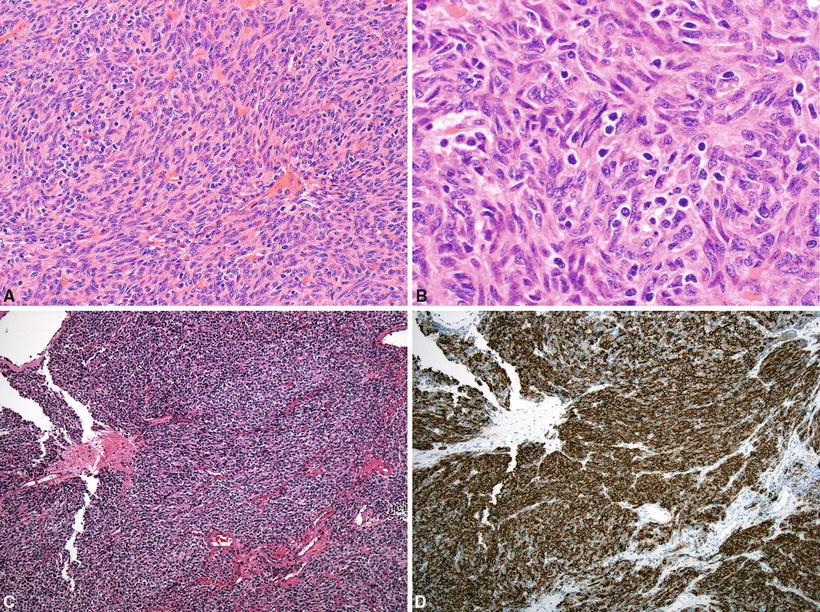

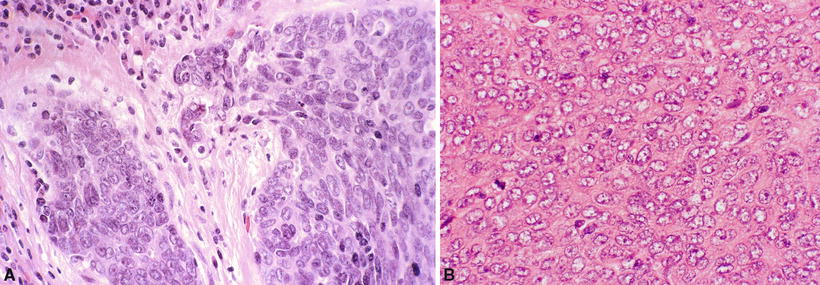

Fig. 26.14.

Thymic carcinoma , undifferentiated (nonkeratinizing type) (A, B). Note infiltrative malignant cells with prominent nucleoli and mitotic figures.

Macroscopic

♦

Thymic carcinomas show a homogeneous, yellow to gray cut surface with hemorrhage, necrosis, and infiltrating borders

Microscopic

♦

Morphologically these tumors are similar to carcinoma in other organ systems and demonstrate cytologic features of malignancy. They usually lack cortical-type immature T lymphocytes

♦

The International Thymic Malignancy Interest Group (ITMIG) proposed criteria for the diagnosis of thymic carcinoma including major criteria (required for diagnosis) and minor criteria (supportive/helpful, but not required for diagnosis)

Major criteria: clear-cut atypia of tumor epithelial cells with the severity typical of carcinoma, exclusion of “thymoma with atypia and/or anaplasia” and of typical or atypical carcinoids, and exclusion of metastasis to the thymus and germ cell and mesenchymal tumors with epithelial features

Minor criteria: infiltrative growth pattern, small tumor cell nests within desmoplastic stroma, absence of TdT+ T cells (with rare exceptions), epithelial expression of CD5 and CD117, and extensive expression of GLUT1 and MUC1a

Features compatible with thymic carcinoma (which are also characteristic of thymoma): invasion with pushing borders, occurrence of perivascular spaces, occurrence of “Hassall-like” epidermoid whorls and/or of myoid cells, and occurrence of (usually rare) TdT+ T cells

Subtypes

•

Common

◦

Keratinizing or nonkeratinizing SCC

◦

Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma

◦

Epstein-Barr virus associated (some cases)

•

Rare

◦

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma

◦

Adenosquamous carcinoma

◦

Basaloid carcinoma

◦

Papillary adenocarcinoma

◦

Adenocarcinoma

◦

Small cell undifferentiated carcinoma

◦

Large cell undifferentiated (anaplastic) carcinoma

◦

Sarcomatoid carcinoma, spindle cell carcinoma, and carcinosarcoma

◦

Clear cell carcinoma

◦

Hepatoid carcinoma

◦

Rhabdoid carcinoma

Immunohistochemistry

♦

Neoplastic epithelial cells are positive for keratin, EMA, CEA, B72.3, and infrequently Leu-7 (CD57)

♦

The epithelial cells in thymic carcinoma cells are usually positive for CD5 (CD5 usually negative in carcinomas other than thymic primary), GLUT1, and CD117

♦

Infiltrating lymphocytes are CD1a, CD99, and TdT negative

♦

Foxn1 and CD205 are markers for thymic carcinoma but typically only used in the research setting or at referral centers

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Thymoma (see above)

♦

Carcinoma metastatic to or invading anterior mediastinum (particularly carcinoma of the lung) and malignant mesothelioma

♦

Thymic squamous carcinoma often exhibits lobulated growth pattern, central sclerosis, and abrupt keratinization simulating Hassall corpuscles. Other subtypes of thymic carcinoma cannot be differentiated based solely on histology (thymic carcinoma is a diagnosis of exclusion – in the presence of malignant epithelial tumor located in the thymic region in the absence of known primary). CD5 positivity for tumor cells supports the diagnosis of primary thymic carcinoma

♦

Germ cell tumors

PLAP+, human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) (see section on “Germ Cell Tumors”)

♦

Primary mediastinal (thymic) large B-cell lymphoma (diffuse large cell lymphoma with sclerosis)

Leukocyte common antigen (LCA)+, CD20 (B-cell marker)+, keratin−, and EMA−

♦

Carcinoma showing thymus-like elements (CASTLE)

Extremely rare tumor of the thyroid gland or soft tissues of the neck morphologically and immunohistochemically similar to thymic carcinoma

Generally has better prognosis with more indolent course

Thymic Carcinoid (Including Atypical Carcinoid)

Clinical

♦

Thymic carcinoids are commonly seen in adults, with a male predominance. Radiologically nonfunctional carcinoids are large, radiopaque, noncystic anterior mediastinal masses with/without fine calcification. Functional carcinoids (associated with Cushing syndrome) are usually of small size and detected by CT scan

♦

Carcinoid syndrome is extremely rare. Functional tumors have a more aggressive course, invade locally, but metastasize infrequently. Occasionally they are associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome (MEN) types 1 or 2a or carcinoid tumors of other sites, such as bronchus and ileum. Overall thymic carcinoids have an approximately 50% 5-year survival. Atypical carcinoids have increased metastatic potential and a survival of approximately 25%. Treatment often consists of multimodal therapy

Macroscopic

♦

Thymic carcinoids are solid, well circumscribed, but not encapsulated (Fig. 26.15A)

Fig. 26.15.

(A) Thymic carcinoid tumor . The hemorrhagic appearance denotes prominent tumor vascularity (scale = 1 cm). (B) Typical carcinoid tumor. Note uniform appearance of cells in a neuroendocrine nesting pattern.

♦

Appear as a lobulated, yellow-tan, or hemorrhagic mass

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree