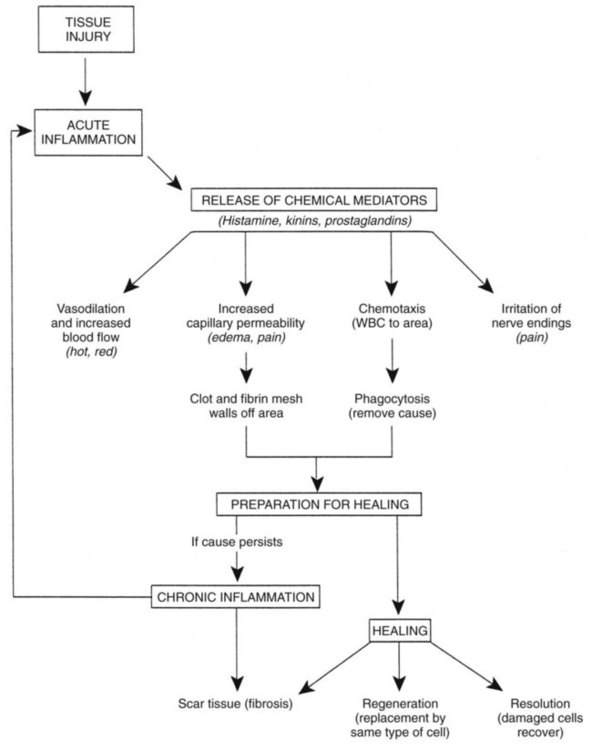

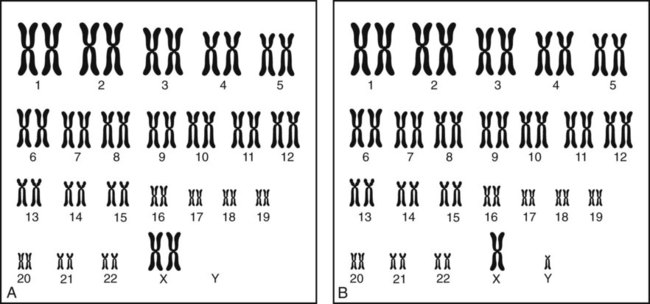

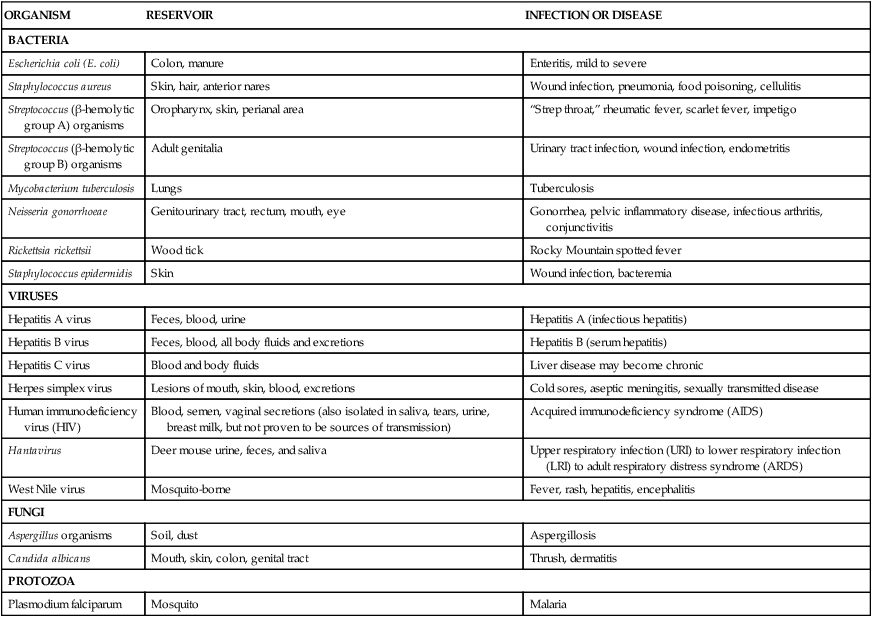

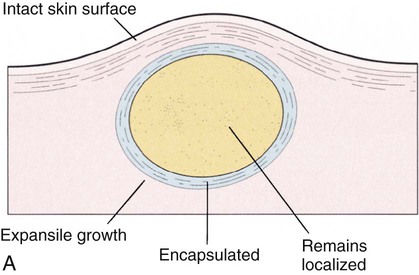

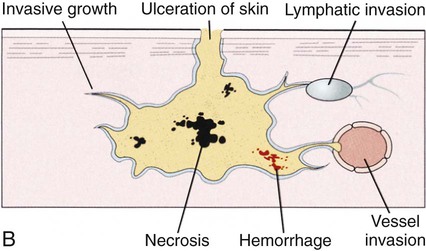

After studying Chapter 1, you should be able to: 1. Explain how a pathologic condition affects the homeostasis of the body. 2. Describe the difference between: Benign and malignant neoplasms 3. Identify the predisposing factors of disease. 4. Describe the ways in which pathogens may cause disease. 5. Track the essential steps in diagnosis of disease. 6. List the prevention guidelines for cancer. 7. Explain the inflammation response to disease. 8. Describe the hospice concept of care. 9. Name two ways an individual can practice positive health behavior. 10. Describe (a) the physiology of pain, (b) how pain may be treated, and (c) what is meant by referred pain. 11. Define the holistic approach to medical care. 12. Describe examples of nontraditional medical therapies. 13. Define integrative medicine. 14. Discuss the principles and goals of patient teaching. 15. List some health effects of exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke. Age. From complications during pregnancy and the postpartum period to maladies associated with aging, some increased risks of diseases are simply intrinsic to one’s stage in the human life cycle. Gender. Certain diseases are more common in women (e.g., multiple sclerosis and osteoporosis) and other disorders are more common in men (e.g., gout and Parkinson’s disease). Lifestyle. Occupation, habits, or one’s usual manner of living can have negative cumulative effects that can threaten a person’s health. It is possible to alter some known risk factors associated with lifestyle, thereby promoting health instead of predisposing one to disease; examples include smoking, excessive drinking of alcohol, risky sexual behavior, poor nutrition, lack of exercise, and certain psychological stressors. Environment. Air and water pollution is considered a major risk factor for illnesses such as cancer and pulmonary disease. Poor living conditions, excessive noise, chronic psychological stress, and a geographic location conducive to disease proliferation also are environmental risk factors. Heredity. Genetic predisposition (inheritance) currently is considered a major risk factor. Family histories of coronary disease, cancer, certain arthritic conditions, and renal disease are known hereditary risk factors. Many other genetic links to diseases are rapidly being discovered. Hereditary factors in disease that appear regularly in successive generations are likely to affect males and females equally. Hereditary or genetic diseases often develop as a result of the combined effects of inheritance and environmental factors. Examples are mental illness, cancer, hypertension, heart disease, and diabetes. Some evidence shows that smoking, a sedentary lifestyle, and a diet high in saturated fat, combined with a positive family history, compound a person’s risk for heart disease and cancer. Schizophrenia may result from a combination of genetic predisposition and numerous psychological and sociocultural causes. Acute inflammation, an exudative response, attempts to wall off, destroy, and digest bacteria and dead or foreign tissue. Vascular changes allow fluid to leak into the site; this fluid contains chemicals that permit phagocytic activity by white blood cells. The process prevents the spread of infection through antibody action and other chemicals released by cells with more specific immune activity. After the mechanisms of inflammation have contained the insult and “cleaned up” the damaged area, repair and replacement of tissue can begin (Figure 1-1). A normal inflammatory response can be inhibited by immune disorders, chronic illness, or the use of certain medications, especially long-term steroid therapy. The sources of infection can be endogenous (originating within the body) or exogenous (originating outside the body). Modes of transmission of pathogenic organisms are direct or indirect physical contact, inhalation or droplet nuclei, ingestion of contaminated food or water, or inoculation by an insect or animal. Pathogenic agents include bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa (Table 1-1). E1-2 TABLE 1–1 Common Pathogens and Some Infections or Diseases That They Produce Modified from Potter P, Perry A: Fundamentals of nursing: concepts, process, and practice, ed 6, St Louis, 2006, Mosby. Every cell in the body is coded with genetic information arranged on 23 pairs of chromosomes; one chromosome from each pair is inherited from the father and the other from the mother. The X and Y chromosomes are known as the sex chromosomes, whereas the remaining 22 pairs are called autosomes. Each cell in an individual’s body contains the same chromosomes and genetic code (genotype). A karyotype is an ordered arrangement of photographs of a full chromosome set (Figure 1-2). Genes, the basic units of heredity, are small stretches of a DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) molecule, situated at a particular site on a chromosome. The main modes of inheritance for genetic diseases are as follows: The following examples of genetic abnormalities are discussed in this book: Cancer, a leading cause of death in the United States, refers to a group of diseases characterized by uncontrolled cell proliferation. This abnormal growth leads to the development of tumors or neoplasms, a relentlessly growing mass of abnormal cells that proliferates at the expense of the healthy organism. Tumors are characterized as malignant or benign and according to the cell type and tissue of origin (Tables 1-2 and 1-3). Some of the main general types of cancer are carcinoma, cancer of the epithelial cells; sarcoma, cancer of the supportive tissues of the body, such as bone and muscle; lymphoma, cancer arising in the lymph nodes and tissues of the immune system; leukemia, cancer of blood cell precursors; and melanoma, cancer of the melanin-producing cells of the body. TABLE 1–2 Comparison of Benign and Malignant Tumors TABLE 1–3 Classification of Neoplasms by Tissue of Origin From Black JM, Matassarin-Jacobs E: Medical-surgical nursing, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2001, Saunders. Cancer is actually many different diseases with numerous causes. Cancer may be caused by both external exposure to carcinogens (chemicals, radiation, and viruses) and internal factors (hormones, immune conditions, and inherited mutations). Ten years or longer may pass between exposures or mutations and the onset of detectable cancer. Cancer can develop in anyone, but the frequency increases with age. Figure 1-3 shows the leading sites of cancer incidence and death. • Consume a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains and low in saturated and trans fats • Eliminate active and passive exposure to cigarette smoke • Limit skin exposure to sunlight • Avoid excessive exposure to radiation and radon • Avoid chemical agents known to be carcinogenic • Protect against sexually transmitted infections, including getting the HPV vaccine Although a number of different staging systems exist, the majority of cancers use a TNM system. TNM staging assesses the neoplasm in three different areas: the size or extent of the primary tumor (T), the extent of regional lymph node involvement by the tumor (N), and the number of distant metastases (M). Once all three parameters are defined, they are combined to assign a stage number of I, II, III, or IV to the cancer. One is an early stage tumor and carries the best prognosis, whereas IV is the most advanced stage. Within each stage, subcategories are defined (Ia, Ib, etc.) to further aid in treatment planning and facilitation of communication between institutions and physicians. See Table 1-4 for an example of staging. TABLE 1–4 Melanoma Staging System of the American Joint Committee on Cancer

Mechanisms of Disease, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Pathology at First Glance

Mechanisms of Disease

Predisposing Factors

Inflammation and Repair

Infection

ORGANISM

RESERVOIR

INFECTION OR DISEASE

BACTERIA

Escherichia coli (E. coli)

Colon, manure

Enteritis, mild to severe

Staphylococcus aureus

Skin, hair, anterior nares

Wound infection, pneumonia, food poisoning, cellulitis

Streptococcus (β-hemolytic group A) organisms

Oropharynx, skin, perianal area

“Strep throat,” rheumatic fever, scarlet fever, impetigo

Streptococcus (β-hemolytic group B) organisms

Adult genitalia

Urinary tract infection, wound infection, endometritis

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Lungs

Tuberculosis

Neisseria gonorrhoeae

Genitourinary tract, rectum, mouth, eye

Gonorrhea, pelvic inflammatory disease, infectious arthritis, conjunctivitis

Rickettsia rickettsii

Wood tick

Rocky Mountain spotted fever

Staphylococcus epidermidis

Skin

Wound infection, bacteremia

VIRUSES

Hepatitis A virus

Feces, blood, urine

Hepatitis A (infectious hepatitis)

Hepatitis B virus

Feces, blood, all body fluids and excretions

Hepatitis B (serum hepatitis)

Hepatitis C virus

Blood and body fluids

Liver disease may become chronic

Herpes simplex virus

Lesions of mouth, skin, blood, excretions

Cold sores, aseptic meningitis, sexually transmitted disease

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

Blood, semen, vaginal secretions (also isolated in saliva, tears, urine, breast milk, but not proven to be sources of transmission)

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)

Hantavirus

Deer mouse urine, feces, and saliva

Upper respiratory infection (URI) to lower respiratory infection (LRI) to adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

West Nile virus

Mosquito-borne

Fever, rash, hepatitis, encephalitis

FUNGI

Aspergillus organisms

Soil, dust

Aspergillosis

Candida albicans

Mouth, skin, colon, genital tract

Thrush, dermatitis

PROTOZOA

Plasmodium falciparum

Mosquito

Malaria

Genetic Diseases

Cancer

CHARACTERISTICS

BENIGN

MALIGNANT

Mode of growth

Relatively slow growth by expansion; encapsulated; cells adhere to each other

Rapid growth; invades surrounding tissue by infiltration

Cells under microscopic examination

Resemble tissue of origin; well differentiated; appear normal

Do not resemble tissue of origin; vary in size and shape; abnormal appearance and function

Spread

Remains localized

Metastasis; cancer cells carried by blood and lymphatics to one or more other locations; secondary tumors occur

Other properties

No tissue destruction; not prone to hemorrhage; may be smooth and freely movable

Ulceration and/or necrosis; prone to hemorrhage; irregular and less movable

Recurrence

Rare after excision

A common characteristic

Pathogenesis

Symptoms related to location with obstruction and/or compression of surrounding tissue or organs; usually not life-threatening unless inaccessible

Cachexia; pain; fatal if not controlled

TISSUE OF ORIGIN

BENIGN

MALIGNANT

Connective tissue

Sarcoma

Embryonic fibrous tissue

Myxoma

Myxosarcoma

Fibrous tissue

Fibroma

Fibrosarcoma

Adipose tissue

Lipoma

Liposarcoma

Cartilage

Chondroma

Chondrosarcoma

Bone

Osteoma

Osteogenic sarcoma

Epithelium

Carcinoma

Skin and mucous membrane

Papilloma

Squamous cell carcinoma

Glands

Basal cell carcinoma

Transitional cell carcinoma

Adenoma

Adenocarcinoma

Cystadenoma

Cystadenocarcinoma

Pigmented cells (melanocytes)

Nevus

Malignant melanoma

Endothelium

Endothelioma

Blood vessels

Hemangioma

Hemangioendothelioma

Hemangiosarcoma

Kaposi sarcoma

Lymph vessels

Lymphangioma

Lymphangiosarcoma

Lymphangioendothelioma

Bone marrow

Multiple myeloma

Ewing sarcoma

Leukemia

Lymphoid tissue

Malignant lymphoma

Lymphosarcoma

Reticulum cell sarcoma

Muscle tissue

Smooth muscle

Leiomyoma

Leiomyosarcoma

Striated muscle

Rhabdomyoma

Rhabdomyosarcoma

Nerve tissue

Nerve fibers and sheaths

Neuroma

Neurinoma

(Neurilemoma)

Neurogenic sarcoma

Neurofibroma

(Neurofibrosarcoma)

Ganglion cells

Ganglioneuroma

Neuroblastoma

Glial cells

Glioma

Glioblastoma

Meninges

Meningioma

Malignant meningioma

Gonads

Dermoid cyst

Embryonal carcinoma

Embryonal sarcoma

Teratocarcinoma

PRIMARY TUMOR (pT)

pTX

Primary tumor cannot be assessed.

pTO

No evidence of primary tumor

pTis

Melanoma in situ (atypical melanotic hyperplasia, severe melanotic dysplasia), not an invasive lesion (Clark’s Level I)

pT1

Tumor 0.75 mm or less in thickness and invades the papillary dermis (Clark’s Level III)

pT3

Tumor more than 1.5 mm but not more than 4 mm in thickness and/or invades the reticular dermis (Clark’s Level IV)

pT3a

Tumor more than 1.5 mm but not more than 3 mm in thickness

pT3b

Tumor more than 3 mm but not more than 4 mm in thickness

pT4

Tumor more than 4 mm in thickness and/or invades the subcutaneous tissue (Clark’s Level V) and/or satellite(s) within 2 cm of the primary tumor

pT4a

Tumor more than 4 mm in thickness and/or invades the subcutaneous tissue

pT4b

Satellite(s) within 2 cm of primary tumor

LYMPH NODE (N)

NX

Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed.

NO

No regional lymph node metastasis

N1

Metastasis 3 cm or less in greatest dimension in any regional lymph nodes

N2

Metastasis more than 3 cm in greatest dimension in any regional lymph node(s) and/or in-transit metastasis

N2a

Metastasis more than 3 cm in greatest dimension in any regional lymph node(s)

N2b

In-transit metastasis

N2c

Both (N2a and N2b)

DISTANT METASTASIS (M)

MX

Presence of distant metastasis cannot be assessed.

MO

No distant metastasis

M1

Distant metastasis

M1a

Metastasis in skin or subcutaneous tissue of lymph node(s) beyond the regional lymph nodes

M1b

Visceral metastasis

STAGE GROUPING

Stage I

pT1, pT2

NO

MO

NO

MO

Stage II

pT3

NO

MO

Stage III

pT4, Any pT

NO

MO

N1, N2

MO

Stage IV

Any pT

Any N

M1 ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree