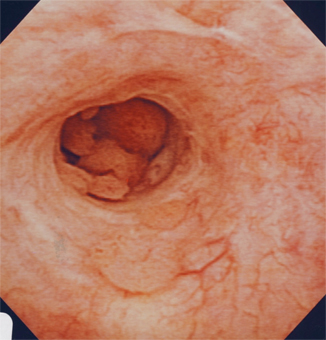

Fig. 6.1

Urethroscopic/cystoscopic appearance of primary papillary urothelial carcinoma of the prostatic urethra. Note the visual similarity to Fig. 6.2 depicting a prostatic ductal adenocarcinoma

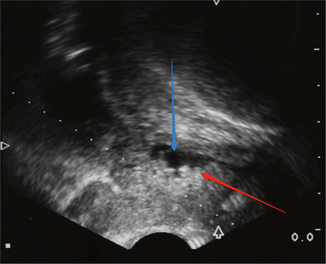

Fig. 6.2

Urethroscopic/cystoscopic appearance of prostatic ductal adenocarcinoma involving the prostatic urethra. Patient presented with hematuria and urinary obstruction, and the lesion was initially thought to be papillary urothelial carcinoma

Carcinoma-in-situ (CIS) of the prostatic urethra is almost always associated with a bladder tumor. In a large study of over 1500 patients with primary bladder tumors, 2.5 % had CIS in the prostatic urethra [3]. CIS of the prostatic urethra may evolve to stromal disease, which has a virulent course. CIS of the bladder is best managed with local resection and a full transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP). The TURP should certainly include the bladder neck as well. This procedure will allow for detection of stromal disease, and will also permit intravesical chemo/immunotherapy to come in contact with the prostatic epithelium [4]. The first line therapy is likely to be Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG). If patients do get BCG to the prostate, transient elevations in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) will be noted, generally resolving in 3 months. The response rate to BCG is very good, with complete response noted in 70–100 % of patients with prostate-only CIS [5]. It is vital to note that such patients will need to be followed closely, not only with cystourethroscopy, but also cytology , as lesions may not be visible. If a positive cytology is detected, but no obvious lesions are seen, random biopsies should be considered. If these biopsies are negative, attention should be given to upper tract evaluation. It is important to stress that the endoscopic evaluation of the bladder should be thorough, especially in the region of the trigone, as bladder trigone involvement is often predictive of prostate stromal involvement. A high proportion of patients, approximately one in three, will experience relapse and progression, requiring radical cystoprostatectomy [6].

Prostatic stromal invasion is a good surrogate marker of tumor virulence, and will help in the disease management to counsel patients that a very high degree of metastases would be found. Prostate stromal involvement mandates a radical operation to remove bladder and prostate, and management principles do not include transurethral operations. Shen et al. found that 3/4 patients with stromal involvement had malignant adenopathy, with a low 5-year survival rate of 32 % [7]. Although there is little consensus in the literature, neoadjuvant chemotherapy and an extended lymph node dissection may be of benefit.

Mucin-Producing Urothelial-Type Adenocarcinoma of the Prostate

Mucin-producing urothelial-type adenocarcinoma of the prostate is a rare tumor that arises from the prostatic urethra, with the largest series consisting of 15 patients [8]. Patients often present with obstructive urinary symptoms. Some may have mucusuria, which is reported to be a specific finding, but is a sign also found in mucinous prostatic adenocarcinoma [8]. The histologic appearance, from TURP and prostate biopsy specimens, and clinical presentation can be similar to other diseases. As such, additional tests should be completed to ensure a definitive diagnosis. Cystoscopic evaluation may help to rule out a metastatic nonurachal adenocarcinoma of the bladder [8]. A colonoscopy, with immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of tissue biopsies, can rule out metastatic colonic adenocarcinoma [9]. With regards to serological markers, PSA is usually within normal limits, as the cancer does not develop from prostatic acini [8, 9]. There may also be a potential benefit in looking for precursor lesions. In one study, only one third of specimens did not have precursor lesions, such cystitis glandularis and villous adenoma, and their absence was attributed to sampling issues and destruction of the surface components by the infiltrating tumor [8].

With such a small number of cases describing mucin-producing urothelial-type adenocarcinoma of the prostate, treatment has not been standardized. However, these tumors are reported to be refractory to hormonal therapy [8]. Most case reports present patients treated with surgery, with varying degrees of success. In one report, consisting of two patients, one patient had no signs of recurrence 1 year after radical prostatectomy, while the other patient had local recurrence 4 years after simple prostatectomy [10]. In a series of 15 patients, all eight patients treated with radical prostatectomy had extraprostatic extension of their disease. Furthermore, eight patients out of the cohort died at an average of 49.2 months from presentation [8]. Although information about this disease is limited, an accurate diagnosis is essential to distinguish it from conventional or mucinous prostatic adenocarcinomas which respond to androgen deprivation therapy.

Mucinous Adenocarcinoma of the Prostate

Mucinous adenocarcinoma (MC) of the prostate is a rare form of prostate cancer, with many large series reporting less than 0.5 % incidence among prostate specimens [11–14]. It can only be diagnosed with certainty on radical prostatectomy. However, it is important to realize that mucin staining on histology is a nonspecific finding, although many clinicians are not aware of this distinction. Conditions like benign prostatic hyperplasia, prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), and signet ring cell prostatic adenocarcinoma often have positive mucin staining [15, 16]. It should be noted that careful examination of the specimen is necessary, as signet ring cell adenocarcinoma portends a worse prognosis than MC and may be less responsive to hormone therapy [17]. In the clinical evaluation of this form of prostate cancer, PSA values have been shown to be elevated in MC, with one series showing PSA elevations in 77.8 % of the patients [18]. One group hypothesized that MRI and MR spectroscopy could be useful in detecting mucin lakes and diagnosing MC. However, their results showed that these modalities could not distinguish mucin lakes, even when they comprised the majority of the tumor volume, and thus, currently, radiographic imaging is not used to make this diagnosis [19].

In a study published in 1999, most cases of MC were either stage C or D on the Whitmore–Jewett staging system [18]. Patients may often present with osteoblastic metastases. The clinical behavior of MC is still unclear. MC was once thought to be an aggressive disease, with one series reporting 8/12 patients presenting with at least stage C disease and all 12 patients developing metastases [13]. However, a recent study reports that MC has a similar, if not better, prognosis than conventional prostatic acinar adenocarcinoma, when treated with radical prostatectomy. The researchers reported a 5-year actuarial PSA progression-free risk of progression for mucinous and non-MC of the prostate of 97.2 and 85.4 %, respectively [20]. With the majority of MC presenting at an advanced stage, surgical therapy may not always be a feasible form of treatment. One case report detailed a patient with MC’s response to hormonal therapy. The patient’s elevated PSA, prostatic-specific acid phosphatase (PSAP), and gamma-seminoprotein returned to normal 2 months after therapy [21]. Furthermore, another study reported a 77.8 % (22/27) response rate for MC treated with endocrine therapy [18]. This study found the 3- and 5-year survival rate to be 50 and 25 %, respectively, in patient with MC. Most studies do not mention the use of chemotherapy in the treatment of MC. However, one study reports the use of chemotherapy, in addition to other modalities, in the treatment of five patients with Gleason score 6 and above MC. Each one of these patients was reported to have expired. Multiple case reports have detailed long-term survival with both radical prostatectomy and hormonal therapy, but further investigation, with larger cohorts, will be necessary to determine which modality provides a better prognosis.

Prostatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma

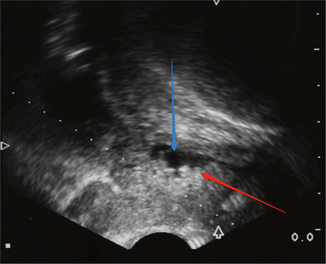

Prostatic ductal adenocarcinoma comprises up to 6.3 % of prostatic adenocarcinomas [22]. Patients often present complaining of obstructive symptoms. On urethroscopy/cystoscopy, this tumor may mimic papillary UC because of the presence of papillary fronds (Fig. 6.2). Transrectal ultrasound may also be helpful (Fig. 6.3) in the differential diagnosis. In a series of 55 patients, 7/8 patients with primary duct adenocarcinoma of the prostate and 44/47 patients with secondary duct adenocarcinoma reported obstructive urinary symptoms [22]. Since this tumor typically arises from the periurethral or occasionally the peripheral zone of the prostate, diagnosis of prostatic ductal adenocarcinoma is ascertained through examination of tissue specimens from TURP or prostatic needle biopsy [23]. This tumor is frequently mixed with prostatic acinar adenocarcinoma. Other entities can also resemble this disease, including prostatic urethral polyps, hyperplastic benign prostate glands, high-grade PIN, colorectal adenocarcinoma, and papillary UC [24]. As such, IHC staining can be utilized to provide a more accurate diagnosis. Serum PSA levels are often elevated in prostatic ductal adenocarcinoma, with a mean PSA of 12.5 in one series of 23 patients [25]. However, the increase in PSA may not adequately reflect the extent of this disease.

Fig. 6.3

Transrectal ultrasound. The patient has a hyperechoic posterior lesion (red arrow) creating an irregular border in the urethra (blue arrow)

Prostatic ductal adenocarcinoma has been reported to be an aggressive disease. In a series of 15 patients, who appeared to have a resectable tumor, treated with radical prostatectomy, 97 % of the specimens showed extraprostatic extension [26]. Prognosis is dependent on multiple factors, including whether prostatic acinar adenocarcinoma is present and the depth of invasion [22, 27]. The presence of prostatic acinar adenocarcinoma in the specimen, when compared to pure prostatic ductal adenocarcinoma, decreases the median survival from 13.8 to 8.9 years [27]. The 5-year survival rate decreases from 42 to 22 % when the secondary periurethral ducts, in addition to the primary periurethral ducts , are involved [22]. Early disease, if localized to the primary periurethral ducts, may be eradicated through TURP, although standard of care is radical prostatectomy [25]. However, a needle biopsy is recommended to determine if there are foci of disease in the peripheral zones of the prostate, warranting a radical prostatectomy or additional treatments. While radiotherapy has not been employed extensively in the treatment of prostatic ductal adenocarcinoma, one series showed that 4/6 patients were alive at 3.2 years after radiotherapy [28]. One case report documented a patient with metastatic prostatic ductal adenocarcinoma. The patient showed a partial biochemical response during nine cycles of palliative docetaxel, but expired soon after completion of chemotherapy [29]. Additional work may determine other effective treatments for this disease. Patients who have this disease warrant a complete evaluation for metastatic disease, including chest imaging. Of note, penile urethral recurrence may occur.

Intraductal Carcinoma of Prostate

Intraductal carcinoma of the prostate (IDC-P) is an aggressive form of prostate cancer , associated with high-grade disease and a poor prognosis. This form of prostate cancer is often associated with invasive cancer [30, 31]. When isolated IDC-P is diagnosed on prostate biopsies, a repeat biopsy is warranted to confirm the concomitance of invasive cancer. Other pathology, such as high-grade PIN, can resemble IDC-P [32]. It is important to note that IDC-P may or may not be associated with a high tumor volume or elevated PSA values. Instead, IDC-P has been associated with low serum PSA values [33]. Once IDC-P is confirmed, definitive therapy is warranted.

One group suggested that radical prostatectomy with extended lymph node dissection may be a feasible approach for treatment [34]. Furthermore, for patients with IDC-P on prostate biopsies, obturator node sampling, seminal vesicle biopsy , and a bone scan prior to prostatectomy may help determine the extent of the disease [35]. The reasoning is that patients with IDC-P on prostate biopsies and transurethral resections have been shown to have early biochemical relapse and metastatic failure when treated with radiotherapy [36]. Similarly, all 11 patients, in a series of 59 patients, with IDC-P on prostate biopsies had clinical relapse after prostatectomy [35]. Androgen ablation therapy, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and radiation therapy are associated with poor results in the treatment of IDC-P. Another study analyzed a series of 115 patients who had androgen ablation, with or without chemotherapy, prior to radical prostatectomy. Of the 42 patients who had biochemical failure, 38 patients had either cribriform pattern or IDC-P [37]. In the EORTC 22863 phase 3 randomized clinical trial, one arm of the study assessed the response of external-beam radiation on patients with prostate cancer. The patients with IDC-P had a median time of 19.9 months to clinical progression, compared to 61.2 months in patients without IDC-P.

Currently, from a clinician standpoint, there has been effort to urge pathologist to report the presence of IDC-P, even when IDC-P comprises a fraction of the specimen. Doing so may help determine a patient’s prognosis and treatment. The inclusion of IDC-P as a preoperative variable was shown to improve the predictive accuracy of post-prostatectomy nomograms in predicting biochemical recurrence [38].

Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Prostate

Primary squamous cell carcinoma (SQCC) of the prostate accounts for less than 1 % of prostatic tumors [39]. This may even be an overestimate, as other pathology , including benign squamous metaplasia, UC with squamous differentiation of the bladder, and the prostatic urethra, may appear histologically similar on the specimens obtained by TURP and prostate biopsy [40]. Conventional prostate cancer can also have a malignant squamous component. A careful review of a patient’s history, including cystoscopy, may provide details suggesting the presence of squamous metaplasia. This entity may arise secondary to prostatic infarct, prior radiation or androgen deprivation therapy, reactive changes after TURP, and granulomatous prostatitis due to BCG therapy [40, 41]. UC with squamous differentiation of the bladder and prostatic urethra must also be ruled out. Cystoscopy and imaging may help determine the presence of these diseases [42]. Symptoms of urinary obstruction and bone involvement, secondary to metastatic disease, are often the first clinical clues to this disease [40]. Serum levels of PSA and PSAP are usually normal, as SQCC does not typically develop from prostatic acini [40, 43]. The tumor often appears as a hypoechoic hypervascular lesion on transrectal ultrasonography (TRUS) and MRI often depicts low lesion signal intensities in the prostate on T2-weighted images [44].

With the low number of cases, treatment of SQCC of the prostate has not been standardized. Furthermore, the efficacy of treatments is currently based on anecdotal evidence. One study presents two patients, including one with positive periaortic and pelvic lymph nodes, who had a radical cystoprostatectomy, pelvic lymphadenectomy, and a urinary diversion. These patients had a survival rate between 25 and 40 months [40]. Another study presented a patient with metastatic osteolytic bone lesion who was treated with cobalt irradiation. This patient survived 8 months after presentation [45]. Hormonal therapy has been reported to be ineffective in the treatment of SQCC of the prostate [46]. From case reports, multimodal therapy appears to have the most benefits. A patient with pelvic relapse treated with cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil, and radiotherapy had a length of survival of 60 months [47]. Surgical treatment with negative margins is thought to be an effective form of treatment. However, the aggressive nature of SQCC of the prostate and metastatic osteolytic lesions at presentation often precludes this form of treatment. Thus, continued research is necessary to determine an effective therapeutic regimen for this form of prostate cancer .

Sarcomatoid Carcinoma of the Prostate

Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the prostate is a rare disease, described mostly in case reports and small series of patients. This disease is thought to arise secondary to radiation therapy or androgen deprivation, as many patients have had prostatic adenocarcinoma treated with these modalities [48, 49]. Diagnosis is made through evaluation of prostatic tissue specimens. A differential diagnosis of phyllodes tumor must be kept in mind. IHC staining can also help distinguish adenocarcinoma from sarcomatoid carcinoma. With the limited tissue specimen a prostate biopsy provides, both epithelial and mesenchymal components may not always be present. To ensure a correct diagnosis of sarcomatoid carcinoma, diseases such as a true prostatic sarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, and inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor need to be ruled out by characteristic microscopic features and IHC staining [49].

Treatment for sarcomatoid carcinoma of the prostate has not been standardized. TURP is often utilized to manage obstructive symptoms. At presentation, this aggressive disease may involve the urinary bladder or penis. Additionally, metastases to the bone, liver, and lungs are also present [49]. In one study, patients were treated with various forms of therapy, including surgery, radiation therapy , androgen deprivation therapy, and various adjuvant chemotherapy regimens, with no significant difference in length of survival. The 5- and 7-year survival rates were 41 and 14 %, respectively, and the median length of survival was 9.5 months. The patient with no evidence of disease at 85 months was treated with a pelvic exenteration and resection of the lung metastases [48]. In another study, nine patients with metastases or bulky local disease were treated with chemotherapy. Three of these patients died within a year and five patients had no response to the chemotherapy [49]. While many cases report the use of chemotherapy in treating patients with sarcomatoid carcinoma of the prostate, a regimen has not been standardized. The use of adriamycin, carboplatinum, cisplatinum, estramustine, etoposide, ifosfamide, taxotere, in various combinations, have been utilized [48–50]. Further work will be necessary to determine an effective form of treatment.

Prostatic Carcinoid

Primary carcinoid tumor, or low-grade neuroendocrine tumor, of the prostate is a rare disease, mostly documented in case reports. The diagnosis of this disease is based on microscopic examination of tissue specimens, acquired by TURP and prostate biopsies, and IHC staining [51, 52]. Prostatic acinar adenocarcinoma with carcinoid features can resemble a carcinoid tumor. An accurate diagnosis is important because prostatic adenocarcinoma is thought to be more aggressive than carcinoid tumor of the prostate [53]. An octreotide scan and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography can be utilized to determine whether the carcinoid tumor has metastasized [52]. One study reported that the tumor appeared as a hypoechoic irregularly shaped mass with increased irregularity on TRUS and a low attenuating mass with peripheral enhancement on CT [44].

Treatment for primary carcinoid tumor of the prostate has not been standardized. With surgical management being the only independent prognostic factor in prostatic small cell carcinoma, a high-grade neuroendocrine tumor, patients with prostatic carcinoid tumor may have the best outcome with surgery [54]. In two case reports, the patients were surgically treated with cystoprostatectomy [51, 52]. However, their outcomes were not reported. Another study reported two patients with metastatic disease to the bone marrow and bone. These patients were both managed by surgical castration. Both died within 10 months of initial diagnosis [55]. Reports about the prognosis of this disease are varied. Some reports have hypothesized that prostatic carcinoid tumor is an indolent disease and that aggressive forms of the disease are in actuality prostatic carcinoma with carcinoid features [51].

Small Cell Carcinoma of the Prostate

Small cell carcinoma of the prostate, a high-grade neuroendocrine tumor, is a rare disease, diagnosed by histologic examination and IHC staining. The most common clinical feature is urinary obstruction. However, symptoms due to metastatic disease and paraneoplastic syndromes may also be present [56]. Serum PSA levels are not usually elevated in pure small cell carcinoma of the prostate. At presentation, CT often reveals bone metastases and abdominal and pelvic lymphadenopathy [44].

This is an aggressive disease that is unresponsive to hormonal therapy. Surgical treatment is not often employed because of the metastatic nature of small cell carcinoma. In one study, 75 % of patient had metastases at presentation [56]. Chemotherapy has been shown to be an effective form of treatment, with 62–72 % of patients having some form of response [56, 57]. However, the chemotherapy regimen has not been standardized. Radiation therapy has also been employed for local control and palliation [58]. The median survival in patients with small cell carcinoma of the prostate is 9–10 months [56, 57]. Elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels and low serum albumin were reported to be predictive of inferior disease-specific survival [59].

Basal Cell Carcinoma of the Prostate

Basal cell carcinoma of the prostate is a rare tumor that comprises less than 0.01 % of malignant tumors of the prostate. A TURP is often completed for obstructive urinary symptoms and examination of the tissue fragments leads to a diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma. While there have been cases of elevated serum PSA in pure basal cell carcinoma of the prostate, serum PSA and PSAP are not usually elevated, unless a component of prostate adenocarcinoma is present [60]. No imaging modality has been effective in diagnosing this disease [61].

Older studies have reported basal cell carcinoma of the prostate to maintain an indolent course [62, 63]. Recent studies indicate that basal cell carcinoma, notably of the adenoid cystic carcinoma histologic variant, may actually be more aggressive, recurring locally after surgery and metastasizing [60, 64]. Treatment for this disease usually involves surgery, including TURP, radical prostatectomy, and pelvic exenteration [60, 61, 64]. In one study, 6/7 patients treated with radical prostatectomy had no evidence of disease at 1 year follow-up [64]. However, the small number of cases does not provide enough evidence to standardize treatment. The type of surgery is usually determined based on the initial extent of the disease. Basal cell carcinoma is reported to be unresponsive to androgen deprivation therapy [65]. Lifelong follow-up is recommended, as this disease may recur locally or metastasize.

Urothelial Carcinoma with Secondary Prostate Involvement

In the USA, the standard of care of the management of muscle invasive UC of the bladder (muscle-invasive bladder cancer, MIBC) is radical cystoprostatectomy as an en bloc procedure, along with an extensive pelvic lymph node dissection . In other countries, definitive combination chemotherapy and radiation therapy are utilized, with the caveat that the failure rate requiring salvage radical cystoprostatectomy is approximately 30 % [66, 67]. There have been attempts at prostate-sparing radical cystectomy , with a view to ameliorating urinary continence, and erectile dysfunction postoperatively, but these should be considered treatments to be undertaken only in the context of a clinical trial [68, 69]. Thus, if a patient has invasive bladder cancer, neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radical cystoprostatectomy is performed.

Recent data have helped to clarify the issue that prostatic stromal invasion from bladder cancer is significantly more common than appreciated in previous series. This mode of invasion may be contiguous or noncontiguous, and happens in approximately equal proportions [70]. Several cystoprostatectomy series using whole-mount methods have shown that stromal invasion is present in approximately half of patients. Richards et al. studied a large series of 121 consecutive whole-mount specimens, and found that 48 % had prostate involvement [71]. Other groups detected stromal invasion in 37–64 % of men undergoing cystoprostatectomy for MIBC [70, 72]. However, stromal invasion is not only restricted to patients with MIBC. Herr and Donat, looking at a large series of 186 patients from Memorial Sloan Kettering with Ta/T1 bladder disease, found that 14 % of patients relapsed with prostatic stromal involvement. In patients with presumed bladder-only refractory CIS and those with multicentric UC, approximately 30 % had prostatic urethral involvement.

With the above data in mind, it is a prudent management principle to diligently inspect the prostatic urethra for lesions if the patient has any degree of bladder cancer, even noninvasive lesions. Biopsies should be taken of lesions, and if possible, underlying prostatic stroma should be evaluated as well with a cold loop resection that includes both the mucosal and the deeper layers. TRUS-guided biopsy is not accurate, and should not be performed to assess for prostate stromal invasion. In the latest edition of the AJCC staging manual (7 ed., 2010), prostate stromal invasion directly from bladder cancer represents a T4a lesion, but interestingly, this T-stage is still classified as Stage III, and the patient may have a 30 % 5-year survival. Subepithelial invasion of prostatic urethra will not constitute T4 staging status.

Colorectal Adenocarcinoma Involving the Prostate

Colorectal adenocarcinoma secondarily involving the prostate is a rare occurrence. Clinicians treating patients who have had colorectal adenocarcinoma or treatment for this disease, and presenting with obstructive urinary symptoms, should acknowledge that there may be direct extension to the prostate from the primary colonic tumor . Diagnosis of this disease is made through evaluation of prostatic tissue specimens, from TURP or prostate biopsies. Bladder and prostatic adenocarcinomas share other similar histologic characteristics with colorectal adenocarcinoma, which may necessitate the use of tests, such as IHC staining, to differentiate these diseases [73]. Serum PSA may also be elevated, even in the absence of prostatic adenocarcinoma, if the prostatic ducts are disrupted [73]. Radiographic evidence of tumor extension and patient presentation can also help in distinguishing these various diseases [73]. However, direct extension may not always be visualized on CT.

There has been a case of hematogenous metastasis to the prostate [74]. Distinguishing colorectal adenocarcinoma from other diseases will help determine the proper form of treatment.

Treatment of secondary colorectal adenocarcinoma involvement of the prostate has not been standardized. Hormonal therapy is known not to be effective in treating colorectal adenocarcinoma [73]. One patient was treated with cystoprostatectomy, partial urethrectomy, and ileal conduit urinary diversion. No metastases were noted during abdominal exploration. At 14 months postoperatively, the patient has been asymptomatic, with an elevated, but stable, CEA level [75]. Another study reported nine cases of colorectal adenocarcinoma involving the prostate, with treatment modalities including surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy. Despite treatment, six of these patients died within 34 months [73]. Further work, including evaluating the role of antibody-based therapy, still needs to be accomplished in order to determine an optimal form of treatment [73].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree