may damage DNA and induce carcinogenesis include:

alkylating agents—leukemia

aromatic hydrocarbons and benzopyrene (from polluted air)—lung cancer

asbestos—mesothelioma of the lung

tobacco—cancer of the lung, oral cavity and upper airways, esophagus, pancreas, kidneys, and bladder

vinyl chloride—angiosarcoma of the liver

Factor | Benign | Malignant |

Differentiation | Well differentiated | Variable |

Effect on body | Cachexia rare; usually not fatal but may obstruct vital organs, exert pressure, produce excess hormones; can become malignant | Cachexia typical, with such symptoms as anemia, loss of weight, and weakness; fatal if untreated |

Growth | Slow expansion; push aside surrounding tissue but don’t infiltrate | Usually infiltrate surrounding tissues rapidly, expanding in all directions |

Limitation | Commonly encapsulated | Seldom encapsulated; in many cases poorly delineated |

Mitotic activity | Variable | Extensive |

Morphology | Cells closely resemble cells of tissue of origin | Cells may differ considerably from those of tissue of origin |

Recurrence | Rare after surgical removal | When removed only by surgery, commonly recur due to infiltration into surrounding tissues |

Spread | No metastasis | Spread via blood and lymph systems; establish secondary tumors |

Tissue destruction | Usually slight | Extensive due to infiltration and metastatic lesion |

early onset of malignant disease

increased incidence of bilateral cancer in paired organs (breasts, adrenal glands, kidneys, and eighth cranial nerve [acoustic neuroma])

increased incidence of multiple primary malignancies in nonpaired organs

abnormal chromosome complement in tumor cells

Their interaction promotes antibody production, cellular immunity, and immunologic memory. Thus, the intact human immune system is responsible for spontaneous regression of tumors.

Aging cells, when copying their genetic material, may begin to err, giving rise to mutations. The aging immune system may not recognize these mutations as foreign and thus may allow them to proliferate and form a malignant tumor.

Cytotoxic drugs decrease antibody production and destroy circulating lymphocytes.

Extreme stress or certain viral infections can depress the immune system.

Increased susceptibility to infection commonly results from radiation, cytotoxic drug therapy, and lymphoproliferative and myeloproliferative diseases, such as lymphatic and myelocytic leukemia. These cause bone marrow depression, which can impair leukocyte function.

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome weakens cell-mediated immunity.

Cancer itself is immunosuppressive; advanced cancer exhausts the immune response. (The absence of immune reactivity is known as anergy.)

and not diagnostic by itself, can signal malignancies of the large bowel, stomach, pancreas, lungs, and breasts. CEA titers range from normal (less than 5 ng) to suspicious (5 to 10 ng) to suspect (greater than 10 ng). CEA serves many valuable purposes:

as a baseline during chemotherapy to evaluate the extent of tumor spread

to regulate drug dosage

to prognosticate after surgery or radiation

to detect tumor recurrence

rest. They are seldom severe enough to require discontinuing radiation but may require a dosage adjustment. (For localized adverse effects, see Radiation’s adverse effects.)

Area radiated | Effect | Management |

Abdomen and pelvis | Cramps, diarrhea, nausea | Administer loperamide and diphenoxylate with atropine. Provide a low-residue diet. Maintain fluid and electrolyte balance. Administer antiemetics as ordered. |

Chest | Esophagitis | Give pain medication. Provide total parenteral nutrition or tube feedings. Maintain fluid balance. |

Lung tissue irritation, persistent nonproductive cough | Explain the importance of not smoking and of avoiding people with upper respiratory infections. Provide steroid therapy as indicated. Provide humidifier if necessary. Administer cough suppressants as indicated. | |

Pericarditis, myocarditis | Give antiarrhythmics, such as procainamide, disopyramide, and phosphate, as indicated. Monitor for heart failure. | |

Head and neck | Alopecia | Gently comb and groom scalp. Use a soft head covering. |

Dental caries | Apply fluoride to teeth prophylactically, encourage use of fluoride mouth rinses, and provide gingival care. | |

Mucositis | Provide a non-alcohol-based mouthwash with viscous lidocaine; cool carbonated drinks; ice pops; and a soft, nonirritating diet. Use soft toothbrushes or swabs. Avoid spicy food and alcohol. | |

Xerostomia (dry mouth) | Encourage good oral hygiene. Consider prescribing an oral saliva replacement. Moist foods are better tolerated than dry foods. | |

Kidneys | Nephritis, lassitude, headache, edema, dyspnea, hypertensive nephropathy, azotemia, anemia | Maintain fluid and electrolyte balance, and watch for signs of renal failure (such as decreased urine output, peripheral edema). Consider prescribing erythropoietin. |

alkylating agents and nitrosoureas, which inhibit cell growth and division by reacting with DNA

antimetabolites, which prevent cell growth by competing with metabolites in the production of nucleic acid

antitumor antibiotics, which block cell growth by binding with DNA and interfering with DNA-dependent ribonucleic acid synthesis

plant alkaloids, which prevent cellular reproduction by disrupting cell mitosis

steroid hormones, which inhibit the growth of hormone-susceptible tumors by changing their chemical environment

Show the patient where radiation therapy takes place, and introduce him to the radiation therapist.

Tell him to remove all metal objects (pens, buttons, jewelry) that may interfere with therapy. Explain that the areas to be treated will be marked with indelible ink and that he must not scrub these areas because it’s important to radiate the same areas each time.

Reinforce the practitioner’s explanation of the procedure, and answer any questions as honestly as you can. If you don’t know the answer to a question, refer the patient to the practitioner.

Teach the patient to watch for and report any adverse effects. Because radiation therapy may increase susceptibility to infection, warn him to avoid people with colds or other infections during therapy. However, emphasize the benefits (such as outpatient treatment) instead of the adverse effects.

Reassure the patient that treatment is painless and won’t make him radioactive. Stress that he’ll be under constant surveillance during radiation administration and should call out if he needs anything.

Increase the patient’s fluid intake before and throughout chemotherapy.

Inform the patient of possible temporary hair loss, and reassure him that his hair should grow back after therapy ends. Suggest a wig or other head covering, and encourage the patient to purchase it before the hair loss.

Check skin for petechiae, ecchymoses, chemical cellulitis, and secondary infection during treatment.

Minimize tissue irritation and damage by checking needle placement before and during infusion if you administer the drug by a peripheral vein. Tell the patient to report any discomfort during infusion. If a vesicant extravasates, stop the infusion, aspirate the drug from the needle, and give the appropriate antidote if available.

Drug Administration has approved several new drugs, which are providing promising results. For example, rituximab—a monoclonal antibody—is effective for treatment of relapsed or refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Obtain a comprehensive dietary history to pinpoint nutritional problems and their past causes such as diabetes; help plan the diet accordingly.

Ask the dietitian to provide a liquid diet high in proteins, carbohydrates, and calories if the patient can’t tolerate solid foods. If the patient has stomatitis, provide soft, bland, nonirritating foods.

Encourage the patient’s family to bring foods from home, if he requests.

Make mealtime as relaxed and pleasant as possible. Encourage the patient to dine with visitors or other patients. Allow choices from a varied menu.

With the practitioner’s approval, you may suggest that the patient drink a glass of wine before dinner to stimulate the appetite and aid relaxation.

Encourage the patient to drink eight 8-oz (236.6 ml) glasses of noncaffeinated liquids per day. Urge him to drink juice or other caloric beverages instead of water.

Suggest frequent, small meals if he can’t tolerate normal ones.

Avoid strong-smelling foods.

remission; even in advanced disease, you can offer short-term achievable goals. To help a patient cope with cancer, make sure you understand your own feelings about it. Then listen sensitively to the patient so you can offer genuine understanding and support. When caring for a patient with terminal cancer, increase your effectiveness by seeking out someone to help you through your own grieving.

Patients are alert and active during the day.

Patients no longer need to suffer pain while awaiting their injections.

Patients are free from pain caused by injections.

The nursing staff is free for other clinical duties.

Hypercalcemia

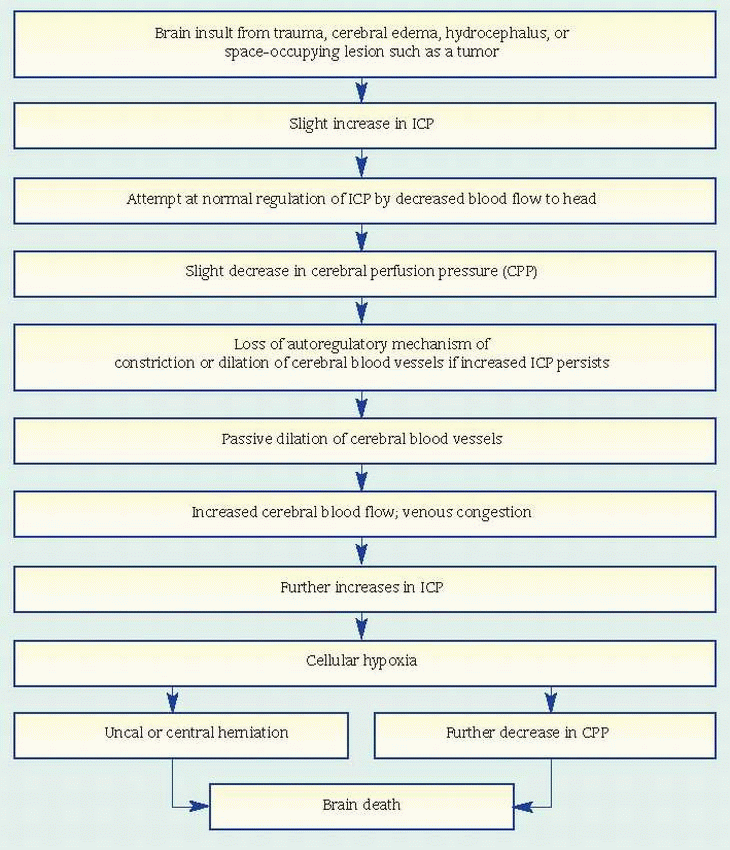

Brain herniation

Coma

Respiratory or cardiac arrest

Seizures

Tumor | Clinical features |

Astrocytoma | |

▪ Second most common malignant glioma (about 10% of all gliomas) ▪ Occurs at any age; incidence higher in males ▪ Usually occurs in white matter of cerebral hemispheres; may originate in any part of the central nervous system ▪ Cerebellar astrocytomas usually confined to one hemisphere | General ▪ Headache; mental activity changes ▪ Decreased motor strength and coordination ▪ Seizures; scanning speech ▪ Altered vital signs Localizing ▪ Third ventricle: changes in mental activity and level of consciousness, nausea, pupillary dilation and sluggish light reflex; later—paresis or ataxia ▪ Brain stem and pons: early—ipsilateral trigeminal, abducens, and facial nerve palsies; later—cerebellar ataxia, tremors, other cranial nerve deficits ▪ Third or fourth ventricle or aqueduct of Sylvius: secondary hydrocephalus ▪ Thalamus or hypothalamus: various endocrine, metabolic, autonomic, and behavioral changes |

Ependymoma | |

▪ Rare glioma ▪ Most common in children and young adults ▪ Usually locates in fourth and lateral ventricles | General ▪ Similar to oligodendroglioma ▪ Increased intracranial pressure (ICP) and obstructive hydrocephalus, depending on tumor size |

Glioblastoma multiforme (spongioblastoma multiforme) | |

▪ Peak incidence at 50 to 60 years; twice as common in males; most common glioma (accounts for 60% of all gliomas) ▪ Unencapsulated, highly malignant; grows rapidly and infiltrates the brain extensively; may become enormous before diagnosed ▪ Usually occurs in cerebral hemispheres, especially frontal and temporal lobes (rarely in brain stem and cerebellum) ▪ Occupies more than one lobe of affected hemisphere; may spread to opposite hemisphere by corpus callosum; may metastasize into cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), producing tumors in distant parts of the nervous system | General ▪ Increased ICP (nausea, vomiting, headache, papilledema) ▪ Mental and behavioral changes ▪ Altered vital signs (increased systolic pressure, widened pulse pressure, respiratory changes) ▪ Speech and sensory disturbances ▪ In children, irritability, projectile vomiting Localizing ▪ Midline: headache (bifrontal or bioccipital); worse in the morning; intensified by coughing, straining, or sudden head movements ▪ Temporal lobe: psychomotor seizures ▪ Central region: focal seizures ▪ Optic and oculomotor nerves: visual defects ▪ Frontal lobe: abnormal reflexes, motor responses |

Medulloblastoma | |

▪ Rare glioma ▪ Incidence highest in children ages 4 to 6 ▪ Affects males more commonly than females ▪ Commonly metastasizes via CSF | General ▪ Increased ICP Localizing ▪ Brain stem and cerebrum: papilledema, nystagmus, hearing loss, flashing lights, dizziness, ataxia, paresthesia of face, cranial nerve palsies (V, VI, VII, IX, X, primarily sensory), hemiparesis, suboccipital tenderness; compression of supratentorial area produces other general and focal signs and symptoms |

Meningioma | |

▪ Most common nongliomatous brain tumor (15% of primary brain tumors) ▪ Peak incidence among 50-year-olds; rare in children; more common in females (ratio 3:2) ▪ Arises from the meninges ▪ Common locations include parasagittal area, sphenoidal ridge, anterior part of the base of the skull, cerebellopontine angle, spinal canal ▪ Benign, well-circumscribed, highly vascular tumors that compress underlying brain tissue by invading overlying skull | General ▪ Headache ▪ Seizures (in two thirds of patients) ▪ Vomiting ▪ Changes in mental activity ▪ Similar to schwannomas Localizing ▪ Skull changes (bony bulge) over tumor ▪ Sphenoidal ridge, indenting optic nerve: unilateral visual changes and papilledema ▪ Prefrontal parasagittal: personality and behavioral changes ▪ Motor cortex: contralateral motor changes ▪ Anterior fossa compressing both optic nerves and frontal lobes: headaches and bilateral vision loss ▪ Pressure on cranial nerves causing varying symptoms |

Oligodendroglioma | |

▪ Third most common glioma (accounts for less than 5% of all gliomas) ▪ Occurs in middle adult years; more common in women ▪ Slow-growing | General ▪ Mental and behavioral changes ▪ Decreased visual acuity and other vision disturbances ▪ Increased ICP Localizing ▪ Temporal lobe: hallucinations, psychomotor seizures ▪ Central region: seizures (confined to one muscle group or unilateral) ▪ Midbrain or third ventricle: pyramidal tract symptoms (dizziness, ataxia, paresthesia of the face) ▪ Brain stem and cerebrum: nystagmus, hearing loss, dizziness, ataxia, paresthesia of the face, cranial nerve palsies, hemiparesis, suboccipital tenderness, loss of balance |

Schwannoma (acoustic neurinoma, neurilemoma, cerebellopontine angle tumor) | |

▪ Accounts for about 10% of all intracranial tumors ▪ Higher incidence in women ▪ Onset of symptoms between ages 30 and 60 ▪ Affects the craniospinal nerve sheath, usually cranial nerve (CN) VIII; also, CN V and VII and, to a lesser extent, CN VI and X on the same side as the tumor ▪ Benign, but commonly classified as malignant because of its growth patterns; slow-growing—may be present for years before symptoms occur | General ▪ Unilateral hearing loss with or without tinnitus ▪ Stiff neck and suboccipital discomfort ▪ Secondary hydrocephalus ▪ Ataxia and uncoordinated movements of one or both arms due to pressure on brain stem and cerebellum Localizing ▪ CN V: early—facial hypoesthesia or paresthesia on side of hearing loss; unilateral loss of corneal reflex ▪ CN VI: diplopia or double vision ▪ CN VII: paresis progressing to paralysis (Bell’s palsy) ▪ CN X: weakness of palate, tongue, and nerve muscles on same side as tumor |

|

Carefully document seizure activity (occurrence, nature, and duration).

Maintain airway patency.

Monitor patient safety.

Administer anticonvulsive drugs as ordered. Encourage the patient to wear a medical identification bracelet or necklace that identifies his risk for seizures.

Check continuously for changes in neurologic status, and watch for an increase in ICP.

Monitor temperature carefully. Fever commonly follows hypothalamic anoxia but might also indicate meningitis. Use hypothermia blankets preoperatively and postoperatively to keep the patient’s temperature down and minimize cerebral metabolic demands.

Administer steroids and osmotic diuretics such as mannitol as ordered to reduce cerebral edema. Fluids may be restricted to 1,500 ml/24 hours. Monitor fluid and electrolyte balance to avoid dehydration.

Observe and report signs and symptoms of stress ulcers: abdominal distention, pain, vomiting, and tarry stools. Administer antacids as ordered.

1,500 ml/24 hours. To promote venous drainage and reduce cerebral edema after supratentorial craniotomy, elevate the head of the patient’s bed about 30 degrees. Position him on his side to allow drainage of secretions and prevent aspiration. As appropriate, instruct the patient to avoid Valsalva’s maneuver or isometric muscle contractions when moving or sitting up in bed; these can increase intra-thoracic pressure and thereby increase ICP. Withhold oral fluids, which may provoke vomiting and consequently raise ICP.

Radiation therapy is usually delayed until after the surgical wound heals, but it can induce wound breakdown even then, so observe the wound carefully for infection and sinus formation. Because radiation may cause brain inflammation, watch for signs of rising ICP.

Because chemotherapy—BCNU, CCNU, procarbazine, and temozolomide—used as adjuncts to radiotherapy and surgery can cause delayed bone marrow depression, tell the patient to watch for and immediately report any signs of infection or bleeding that appear within 4 weeks after the start of chemotherapy. Before chemotherapy, give ondansetron or another antiemetic, as ordered, to minimize nausea and vomiting.

Teach the patient and his family signs of recurrence; urge compliance with treatment regimen.

Because brain tumors may cause residual neurologic deficits that disable the patient physically or mentally, begin rehabilitation early. Changes in cognitive function may also be observed and affect daily functional activities. Consult with occupational and physical therapists to encourage independence in daily activities and improve the quality of life. As necessary, provide aids for self-care and mobilization, such as bathroom rails for the wheelchair patient. If the patient is aphasic, arrange for consultation with a speech pathologist.

Legal advice is helpful in forming advance directives such as power of attorney in cases where continued physical or intellectual decline is likely.

Refer the patient for counseling and to national and local support groups to help him cope with this disorder.

Endocrine abnormalities

Diabetes insipidus

frontal headache

visual symptoms, beginning with blurring and progressing to field cuts (hemianopsias) and then unilateral blindness

cranial nerve (III, IV, VI) involvement from lateral extension of the tumor, resulting in strabismus; double vision, with compensating head tilting and dizziness; conjugate deviation of gaze; nystagmus; lid ptosis; and limited eye movements

increased intracranial pressure (ICP) (secondary hydrocephalus)

rhinorrhea, if the tumor erodes the base of the skull

pituitary apoplexy secondary to hemorrhagic infarction of the adenoma. Such hemorrhage may lead to both cardiovascular and adrenocortical collapse

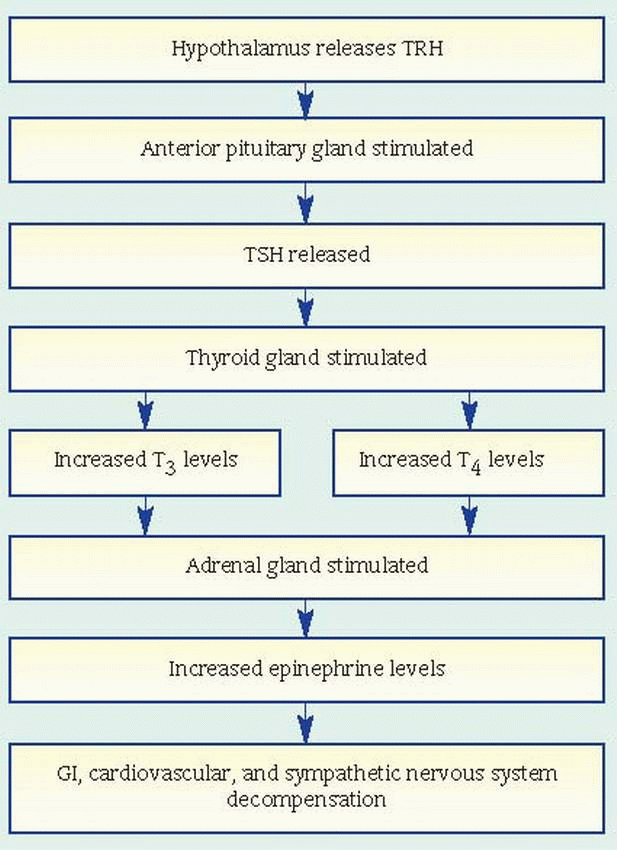

hypopituitarism, to some degree, in all patients with adenoma, becoming more obvious as the tumor replaces normal gland tissue (signs and symptoms include amenorrhea, decreased libido and impotence in men, skin changes [waxy appearance, decreased wrinkles, and pigmentation], loss of axillary and pubic hair, lethargy, weakness, increased fatigability, intolerance to cold, and constipation [because of decreased production of corticotropin and thyroid-stimulating hormone])

addisonian crisis, precipitated by stress and resulting in nausea, vomiting, hypoglycemia, hypotension, and circulatory collapse

diabetes insipidus, resulting from extension to the hypothalamus

prolactin-secreting adenomas (in 70% to 75%), with amenorrhea and galactorrhea

GH-secreting adenomas, with acromegaly

corticotropin-secreting adenomas, with Cushing’s syndrome

Skull X-rays with tomography show enlargement of the sella turcica or erosion of its floor; if GH secretion predominates, X-rays show enlarged paranasal sinuses and mandible, thickened cranial bones, and separated teeth.

Carotid angiogram shows displacement of the anterior cerebral and internal carotid arteries if the tumor mass is enlarging; it also rules out intracerebral aneurysm

Computed tomography scan may confirm the existence of the adenoma and accurately depict its size.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis may show increased protein levels.

Endocrine function tests may contribute helpful information, but results are commonly ambiguous and inconclusive.

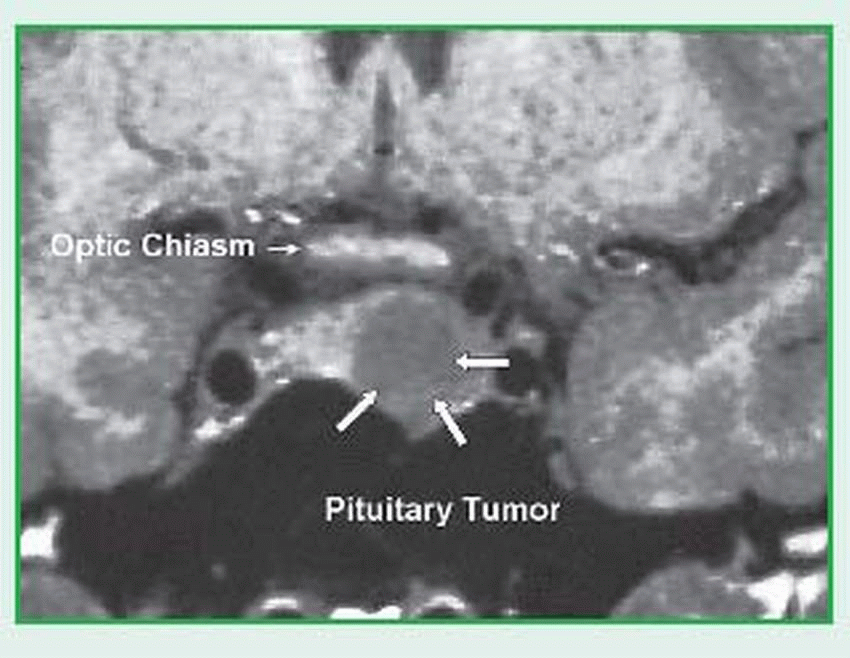

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) differentiates healthy, benign, and malignant tissues as well as arteries and veins. MRI is an excellent modality for viewing the pituitary. (See MRI of the pituitary.)

Conduct a comprehensive health history and physical assessment to establish the onset of neurologic and endocrine dysfunction and provide baseline data for later comparison.

Establish a supportive, trusting relationship with the patient and his family to assist them in coping with the diagnosis, treatment, and potential long-term changes. Make sure they understand that the patient needs lifelong evaluations and, possibly, hormone replacement.

Reassure the patient that some of the distressing physical and behavioral signs and

symptoms caused by pituitary dysfunction (for example, altered sexual drive, impotence, infertility, loss of hair, and emotional instability) will disappear with treatment.

Maintain a safe, clutter-free environment for the visually impaired or acromegalic patient. Re assure him that he’ll probably recover his sight.

Prevent vomiting, which increases ICP. Don’t allow a patient who has had transsphenoidal surgery to blow his nose. Watch for CSF drainage from the nose. Monitor for signs of infection from the contaminated upper respiratory tract. Make sure the patient understands that he’ll lose his sense of smell.

Regularly compare the patient’s postoperative neurologic status with your baseline assessment. (See Postcraniotomy care.)

Monitor intake and output to detect fluid and electrolyte imbalances.

Before discharge, encourage the patient to wear a medical identification bracelet or necklace that identifies his hormone deficiencies and their proper treatment.

Monitor vital signs (especially level of consciousness), and perform a baseline neurologic assessment from which to plan further care and assess the patient’s progress.

Maintain the patient’s airway; suction as necessary.

Monitor intake and output carefully.

Prevent aspiration and vomiting, which increases intracranial pressure.

Observe for cerebral edema, bleeding, and leakage of cerebrospinal fluid.

Provide a restful, quiet environment.

Monitor for postoperative pain or headache

supraglottis (false vocal cords)

glottis (true vocal cords)

subglottis (downward extension from vocal cords [rare])

Airway obstruction

Metastasis

Pain

Difficulty swallowing

tumor size and can include cordectomy, partial or total laryngectomy, supraglottic laryngectomy, or total laryngectomy with laryngoplasty. Primary systemic therapy may be administered concurrently with radiation. Principal agents include cisplatin, fluorouracil, carboplatin, and the taxanes. The goal is to eliminate the cancer and preserve speech. If speech preservation isn’t possible, speech rehabilitation may include esophageal speech or prosthetic devices; surgical techniques to construct a new voice box are still experimental.

Instruct the patient to maintain good oral hygiene. If appropriate, instruct a male patient to shave off his beard.

Encourage the patient to express his concerns before surgery. Help him choose a temporary nonspeaking communication method (such as writing).

If appropriate, arrange for a laryngectomee to visit the patient. Explain postoperative procedures (suctioning, nasogastric [NG] feeding, laryngectomy tube care) and their results (breathing through neck, speech alteration). Also prepare him for other functional losses: He won’t be able to smell, blow his nose, whistle, gargle, sip, or suck on a straw.

Give I.V. fluids and, usually, tube feedings in the initial postoperative period; then resume oral fluids. Keep the tracheostomy tube (inserted during surgery) in place until edema subsides.

Keep the patient from using his voice until he has medical permission (usually 2 to 3 days postoperatively). Then caution him to whisper until healing is complete.

As soon as the patient returns to his bed, place him on his side and elevate his head 30 to 45 degrees. When you move him, remember to support his neck.

The patient will probably have a laryngectomy tube in place until his stoma heals (about 7 to 10 days). This tube is shorter and thicker than a tracheostomy tube but requires the same care. Watch for crusting and secretions around the stoma, which can cause skin breakdown. To prevent crust formation, provide adequate room humidification. Remove crusting with petroleum jelly, antimicrobial ointment, and moist gauze.

Teach stoma care.

Watch for and report complications: fistula formation (redness, swelling, secretions on suture line), carotid artery rupture (bleeding), and tracheostomy stenosis (constant shortness of breath). A fistula may form between the reconstructed hypopharynx and the skin. This eventually heals spontaneously but may take weeks or months. Carotid artery rupture usually occurs in patients who have had preoperative radiation, particularly those with a fistula that constantly bathes the carotid artery with oral secretions.

Tracheostomy stenosis occurs weeks to months after laryngectomy; treatment includes fitting the patient with successively larger tracheostomy tubes until he can tolerate insertion of a large one. If the patient has a fistula, feed him through an NG tube; otherwise, food will leak through the fistula and delay healing. Monitor vital signs (be especially alert for fever, which indicates infection). Record fluid intake and output, and watch for dehydration.

Give frequent mouth care.

Suction gently, unless ordered otherwise. Don’t attempt deep suctioning, which could penetrate the suture line. Suction through both the tube and the patient’s nose because the patient can no longer blow air through his nose; suction his mouth gently.

After insertion of a drainage catheter (usually connected to a wound-drainage system or a GI drainage system), don’t stop suction without the practitioner’s consent. After catheter removal, check dressings for drainage.

Give analgesics as ordered.

If the patient has an NG feeding tube, check tube placement and elevate the patient’s head to prevent aspiration.

Reassure the patient that speech rehabilitation may help him speak again. Encourage contact with the International Association of Laryngectomees and other sources of support.

Support the patient through the grieving process. If the depression seems severe, consider a psychiatric referral.

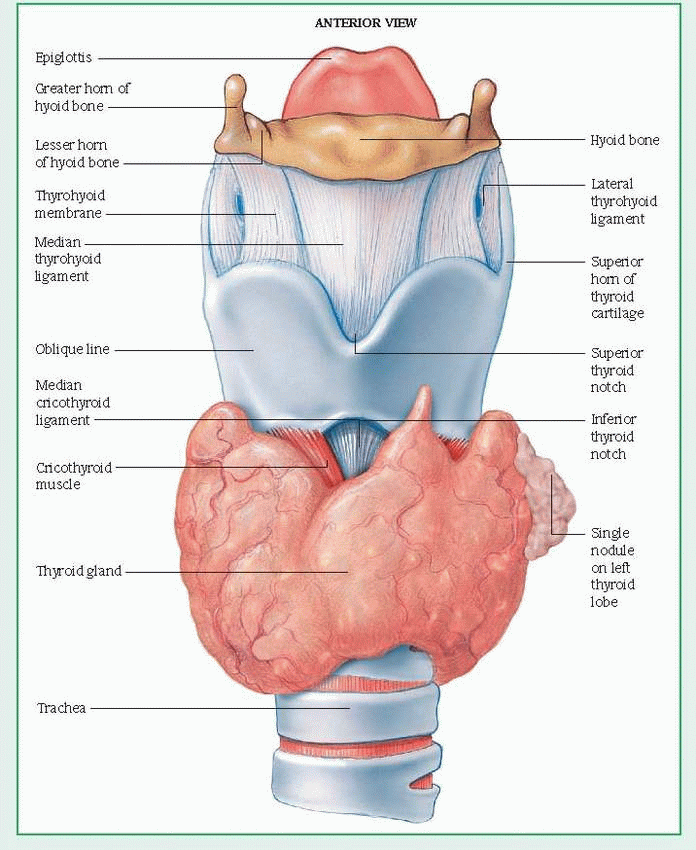

adult females and metastasizes slowly. It’s the least virulent form of thyroid cancer. Follicular carcinoma is less common but more likely to recur and metastasize to the regional nodes and through blood vessels into the bones, liver, and lungs. Medullary carcinoma originates in the parafollicular cells derived from the last branchial pouch and contains amyloid and calcium deposits. It can produce calcitonin, histaminase, corticotropin (producing Cushing’s syndrome), and prostaglandin E2 and F3 (producing diarrhea). Of the three types of medullary carcinoma, sporadic is the most common and isn’t inherited. Multiple endocrine neoplasia, type II (MEN2) is familial; it’s associated with pheo-chromocytoma and parathyroid gland tumors

and is completely curable when detected before it causes symptoms. Untreated, it progresses rapidly. Seldom curable by resection, anaplastic tumors resist radiation and metastasize rapidly. The familial type of medullary cancer is also inherited but only affects the thyroid gland. Thyroid lymphoma begins in the lymphocytes and can move to the thyroid gland.

Dysphagia

Stridor

Low calcium levels

Metastasis

Total or subtotal thyroidectomy, with modified node dissection (bilateral or unilateral) on the side of the primary cancer (papillary or follicular cancer)

Total thyroidectomy and radical neck excision (for medullary, giant, or spindle cell cancer)

Radiation (131I) with external radiation (for inoperable cancer and sometimes postoperatively in lieu of radical neck excision) or alone (for metastasis)

Adjunctive thyroid suppression, with exogenous thyroid hormones suppressing TSH production, and simultaneous administration of an adrenergic blocking agent such as propranolol, increasing tolerance to surgery and radiation

Chemotherapy for symptom-producing, widespread metastasis is limited, but doxorubicin is sometimes beneficial

When the patient regains consciousness, keep him in semi-Fowler’s position, with his head nei ther hyperextended nor flexed, to avoid pressure on the suture line. Support his head and neck with sandbags and pillows; when you move him, continue this support with your hands.

Check serum calcium levels daily; hypocal cemia may develop if parathyroid glands are re moved. Watch for and report other complications: hemorrhage and shock (elevated pulse rate and hypotension), tetany (carpopedal spasm, twitch ing, and seizures), thyroid storm (high fever,

severe tachycardia, delirium, dehydration, and extreme irritability), and respiratory obstruction (dyspnea, crowing respirations, and retraction of neck tissues). (See What happens in thyroid storm.)

Keep a tracheotomy set, suction, and oxygen equipment handy in case of respiratory obstruction. Use continuous steam inhalation in the patient’s room until his chest is clear.

The patient may need I.V. fluids or a soft diet, but many patients can tolerate a regular diet within 24 hours of surgery.

|

rare, accounting for only about 10%. In children, they’re low-grade astrocytomas.

Paralysis

Weakness

Loss of bowel and bladder sphincter control

Sensation of numbness or pain

Pain—Most severe directly over the tumor, radiates around the trunk or down the limb on the affected side and is unrelieved by bed rest. It may worsen when lying down or with straining, coughing, or sneezing. Pain can be diffuse, occurring over all extremities. Generally, it progressively worsens and isn’t relieved by medication.

Motor symptoms—Asymmetric spastic muscle weakness, decreased muscle tone, exaggerated reflexes, and a positive Babinski’s sign. If the tumor is at the level of the cauda equina, muscle flaccidity, muscle wasting, weakness, and progressive diminution in tendon reflexes are characteristic.

Sensory deficits—Contralateral loss of pain, temperature, and touch sensation (Brown-Séquard’s syndrome). These losses are less obvious to the patient than functional motor changes. Caudal lesions invariably produce paresthesia in the nerve distribution pathway of the involved roots.

Bowel and bladder symptoms—Urine retention is an inevitable late sign with cord compression. Early signs include incomplete emptying or difficulty with the urine stream, which is usually unnoticed or ignored. Cauda equina tumors cause bladder and bowel incontinence due to flaccid paralysis.

X-rays show distortions of the intervertebral foramina; changes in the vertebrae or collapsed areas in the vertebral body; and localized enlargement of the spinal canal, indicating an adjacent block.

Myelography identifies the level of the lesion by outlining it if the tumor is causing partial obstruction; it shows anatomic relationship to the cord and the dura. If obstruction is complete, the injected dye can’t flow past the tumor. (This study is dangerous if cord compression is nearly complete because withdrawal or escape of cerebrospinal fluid [CSF]

will allow the tumor to exert greater pressure against the cord.)

Radioisotope bone scan demonstrates metastatic invasion of the vertebrae by showing a characteristic increase in osteoblastic activity.

Computed tomography scan shows cord compression and tumor location.

Frozen section biopsy at surgery identifies the tissue type.

Lumbar puncture may be normal, abnormal, or nonspecific. It may show clear yellow CSF as a result of increased protein levels if the flow is completely blocked. If the flow is partially blocked, protein levels rise, but the fluid is only slightly yellow in proportion to the CSF protein level. Cytology of the CSF may show malignant cells of metastatic carcinoma.

On your first contact with the patient, perform a complete neurologic evaluation to obtain baseline data for planning future care and evaluating changes in his clinical status.

Care of the patient with a spinal cord tumor is basically the same as that for the patient with spinal cord injury and requires psychologic support, rehabilitation (including bowel and bladder retraining), and prevention of infection and skin breakdown. After laminectomy, care includes checking neurologic status frequently, changing position by logrolling, administering analgesics, monitoring frequently for infection, and aiding in early walking. Physical therapy may be needed to improve muscle strength and to improve the ability to function independently when permanent neurologic losses occur.

Help the patient and his family to understand and cope with the diagnosis, treatment, potential disabilities, and necessary changes in lifestyle.

Take safety precautions for the patient with impaired sensation and motor deficits. Use side rails if the patient is bedridden; if he isn’t, encourage him to wear flat shoes, and remove scatter rugs and clutter to prevent falls.

Encourage the patient to be independent in performing daily activities. Avoid aggravating pain by moving the patient slowly and by making sure his body is well aligned when giving personal care. Advise him to use TENS to block radicular pain.

Administer steroids and antacids, as ordered, for cord edema after radiation therapy. Monitor for sensory or motor dysfunction, which indicates the need for more steroids.

Enforce bed rest for the patient with vertebral body involvement until the practitioner says he can safely walk because body weight alone can cause cord collapse and cord laceration from bone fragments.

Logroll and position the patient on his side every 2 hours to prevent pressure ulcers and other complications of immobility.

If the patient is to wear a back brace, make sure he wears it whenever he gets out of bed.

pollutants (asbestos, uranium, arsenic, nickel, iron oxides, chromium, radioactive dust, and coal dust) and familial susceptibility.

Anorexia

Cachexia

Clubbing of fingers and toes

Dysphagia

Dyspnea

Esophageal compression

Hypertrophic osteoarthropathy

Hypoxemia

Phrenic nerve paralysis

Pleural effusion

Tracheal obstruction

Epidermoid and small-cell carcinomas— smoker’s cough, hoarseness, wheezing, dyspnea, hemoptysis, and chest pain

Adenocarcinoma and large-cell carcinoma— fever, weakness, weight loss, anorexia, and shoulder pain

Gynecomastia may result from large-cell carcinoma.

Hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy (bone and joint pain from cartilage erosion due to abnormal production of growth hormone) may result from large-cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma.

Cushing’s and carcinoid syndromes may result from small-cell carcinoma.

Hypercalcemia may result from epidermoid tumors.

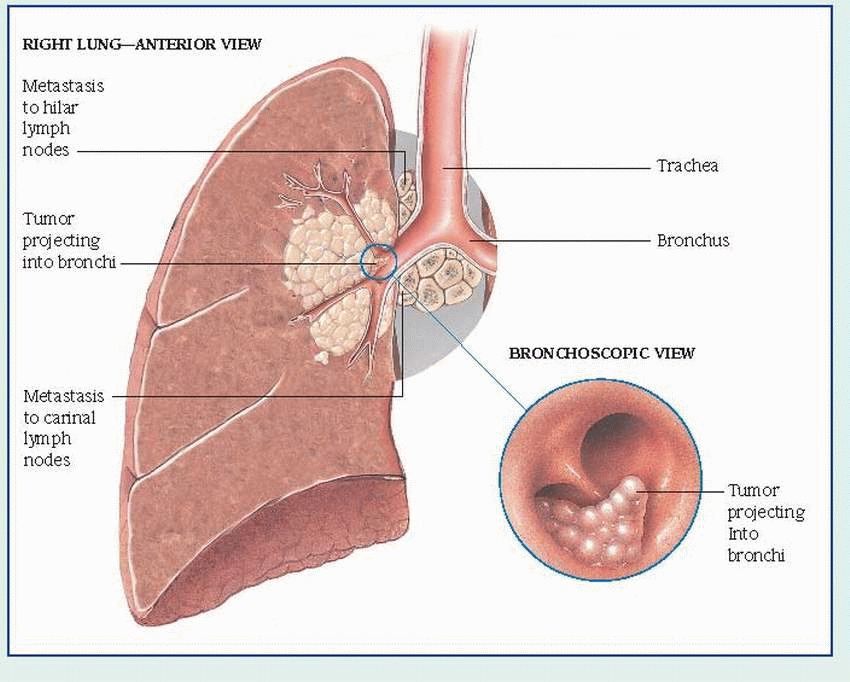

bronchial obstruction: hemoptysis, atelectasis, pneumonitis, dyspnea

cervical thoracic sympathetic nerve involvement: miosis, ptosis, exophthalmos, reduced sweating

chest wall invasion: piercing chest pain, increasing dyspnea, severe shoulder pain radiating down arm

esophageal compression: dysphagia

local lymphatic spread: cough, hemoptysis, stridor, pleural effusion

pericardial involvement: pericardial effusion, tamponade, arrhythmias

phrenic nerve involvement: dyspnea, shoulder pain, unilateral paralyzed diaphragm with paradoxical motion

recurrent nerve invasion: hoarseness, vocal cord paralysis

vena caval obstruction: venous distention and edema of face, neck, chest, and back

Chest X-ray usually shows an advanced lesion, but it can detect a lesion up to 2 years before symptoms appear. It also indicates tumor size and location.

Sputum cytology, which is 75% reliable, requires a specimen coughed up from the lungs and tracheobronchial tree, not postnasal secretions or saliva.

Spiral or helical computed tomography (CT) of the chest may help to delineate the tumor’s size and its relationship to surrounding structures.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is useful for differentiating vascular abnormalities from tumor.

Bronchoscopy can locate the tumor site. Bronchoscopic washings provide material for cytologic and histologic examination. The flexible fiber-optic bronchoscope increases the test’s effectiveness.

Percutaneous needle biopsy of the lungs uses biplane fluoroscopic visual control to detect peripherally located tumors. This allows firm diagnosis in 80% of patients.

Mediastinoscopy with tissue biopsy of accessible metastatic sites includes supraclavicular and mediastinal node and pleural biopsy. Directed needle biopsy may be performed in conjunction with CT scan.

Thoracentesis allows chemical and cytologic examination of pleural fluid.

Supplement and reinforce the information given to the patient by the health care team about the disease and the surgical procedure.

Explain expected postoperative procedures, such as insertion of an indwelling catheter, use of an endotracheal tube or chest tube (or both), dressing changes, and I.V. therapy.

Teach the patient how to perform coughing, deep diaphragmatic breathing, and range-of-motion (ROM) exercises.

Reassure the patient that analgesics will be provided and proper positioning will be implemented to control postoperative pain.

Inform the patient that he may take nothing by mouth beginning after midnight the night before surgery, that he’ll shower with a soaplike antibacterial agent the night or morning before surgery, and that he’ll be given preoperative medications, such as a sedative and an anticholinergic to dry secretions.

Maintain a patent airway, and monitor chest tubes to reestablish normal intrathoracic pressure and prevent postoperative and pulmonary complications.

Check vital signs every 15 minutes during the first hour after surgery, every 30 minutes during the next 4 hours, and then every 2 hours. Watch for and report abnormal respiration and other changes.

Suction the patient as needed, and encourage him to begin deep breathing and coughing as soon as possible. Check secretions often. Initially, sputum will be thick and dark with blood, but it should become thinner and grayish yellow within a day.

Monitor and record closed chest drainage. Keep chest tubes patent and draining effectively. Fluctuation in the water-seal chamber on inspiration and expiration indicates that the chest tube is patent. Watch for air leaks, and report them immediately. Position the patient on the surgical side to promote drainage and lung reexpansion.

Watch for and report foul-smelling discharge and excessive drainage on dressing. Usually, the dressing is removed after 24 hours, unless the wound appears infected.

Monitor intake and output. Maintain adequate hydration.

Watch for and treat infection, shock, hemorrhage, atelectasis, dyspnea, mediastinal shift, and pulmonary embolus.

To prevent pulmonary embolus, apply antiem-bolism stockings and encourage ROM exercises.

Explain possible adverse effects of radiation and chemotherapy. Watch for, treat and, when possible, try to prevent them.

Ask the dietary department to provide soft, nonirritating foods that are high in protein, and encourage the patient to eat high-calorie between-meal snacks.

Give antiemetics and antidiarrheals, as needed.

Schedule patient care activities in a way that helps the patient conserve his energy.

During radiation therapy, administer skin care to minimize skin breakdown. If the patient receives radiation therapy in an outpatient setting, warn him to avoid tight clothing, exposure to the sun, and harsh ointments on his chest. Teach him exercises to help prevent shoulder stiffness.

For patients who smoke, explain the benefits of quitting and encourage them to quit.

Refer smokers who want to quit to the American Cancer Society or smoking-cessation programs or suggest group therapy, individual counseling, or use of smoking-cessation products.

Encourage patients with recurring or chronic respiratory infections and those with chronic lung disease who detect any change in the character of a cough to see their practitioner promptly for evaluation.

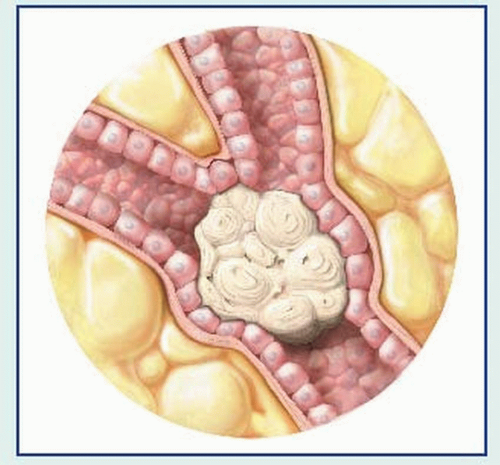

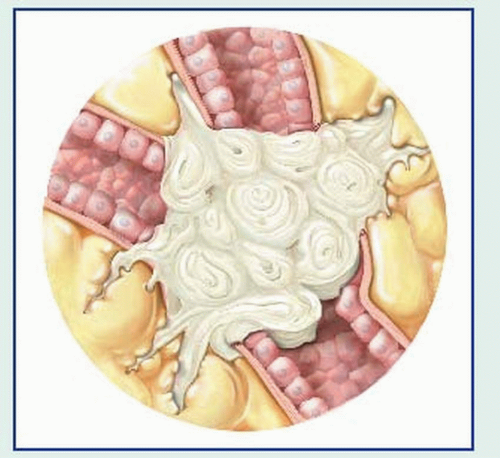

adenocarcinoma—arising from the epithelium

intraductal—developing within the ducts (in cludes Paget’s disease)

infiltrating—occurring in parenchyma of the breast

inflammatory (rare)—reflecting rapid tumor growth, in which the overlying skin becomes edematous, inflamed, and indurated

lobular carcinoma in situ—reflecting tumor growth involving lobes of glandular tissue

medullary or circumscribed—large tumor with rapid growth rate

have long menstrual cycles or began menses early (before age 12) or menopause late (after age 55)

have taken hormonal contraceptives

used hormone replacement therapy for more than 5 years

who took diethylstilbestrol to prevent miscarriage

have never been pregnant

were first pregnant after age 30 have had unilateral breast cancer

have had ovarian cancer—particularly at a young age

were exposed to low-level ionizing radiation

have genetic mutations, such as in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes

were pregnant before age 20

have had multiple pregnancies

are Native American or Asian

According to the most recent data, mortality rates continue to decline in White women and, for the first time, are also declining in younger Black women. Lymph node involvement is the most valuable prognostic predictor. With adjuvant therapy, 70% to 75% of women with negative nodes will survive 10 years or more compared with 20% to 25% of women with positive nodes.

Infection

Decreased mobility

Lymphedema

a lump or mass in the breast (a hard, nontender stony mass is usually malignant)

change in symmetry or size of the breast

change in skin, thickening, scaly skin around the nipple, dimpling, edema (peau d’orange), or ulceration

change in skin temperature (a warm, hot, or pink area; suspect cancer in a nonlactating woman older than childbearing age until proven otherwise)

unusual drainage or discharge (A spontaneous discharge of any kind in a nonbreast-feeding, nonlactating woman warrants thorough investigation; so does any discharge produced by breast manipulation [greenish black, white, creamy, serous, or bloody]. If a breast-fed infant rejects one breast, this may suggest possible breast cancer.)

change in the nipple, such as itching, burning, erosion, or retraction

pain (not usually a symptom of breast cancer unless the tumor is advanced, but it should be investigated)

bone metastasis, pathologic bone fractures, and hypercalcemia

edema of the arm

of the breasts), except for those women who are strongly suspected of having breast cancer. False-negative results can occur in as many as 30% of all tests. Consequently, with a suspicious mass, a negative mammogram should be disregarded, and a fine-needle aspiration or surgical biopsy should be done. Ultrasonography, which can distinguish a fluid-filled cyst from a tumor, can also be used instead of an invasive surgical biopsy.

Surgery involves either mastectomy or lumpectomy. A lumpectomy may be done on an outpatient basis and may be the only surgery needed, especially if the tumor is small and there’s no evidence of axillary node involvement. In many cases, radiation therapy is combined with this surgery.

Chemotherapy, involving various cytotoxic drug combinations, is used as either adjuvant or primary therapy, depending on several factors, including the TNM staging of the cancer, as well as estrogen receptor and HER2 status. The most commonly used antineoplastic drugs are cyclophosphamide, fluorouracil, methotrexate, doxorubicin, vincristine, and paclitaxel. A common drug combination used in both premenopausal and postmenopausal women is cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and paclitaxel.

For individuals with HER2-positive receptors, monoclonal antibodies such as trastuzumab are indicated for adjuvant therapy.

Peripheral stem cell therapy is an option, but it’s rarely used for advanced breast cancer.

Primary radiation therapy before or after tumor removal is effective for small tumors in early stages with no evidence of distant metastasis; it’s also used to prevent or treat local recurrence. Presurgical radiation to the breast in inflammatory breast cancer helps make tumors more surgically manageable.

Estrogen, progesterone, androgen, or antiandrogen aminoglutethimide therapy may also be given to breast cancer patients. The success of these drug therapies—along with growing evidence that breast cancer is a systemic, not local, disease—has led to a decline in ablative surgery.

Teach her how to deep-breathe and cough to prevent pulmonary complications and how to rotate her ankles to help prevent thromboembolism.

Tell her she can ease her pain by lying on the affected side or by placing a hand or pillow on the incision. Preoperatively, show her where the incision will be. Inform her that she’ll receive pain medication and that she need not fear addiction. Remember, adequate pain relief encourages coughing and turning and promotes general well-being. Positioning a small pillow anteriorly under the patient’s arm provides comfort.

Encourage her to get out of bed as soon as possible (even as soon as the anesthesia wears off or the first evening after surgery).

Explain that, after mastectomy, an incisional drain or suction device will be used to remove accumulated serous or sanguineous fluid, thereby promoting healing.

Inspect the dressing anteriorly and posteri orly, reporting bleeding promptly.

Measure and record the amount of drainage; also note the color. Expect drainage to be bloody during the first 4 hours and afterward to become serous.

Check circulatory status (blood pressure, pulse, respirations, and bleeding).

Monitor intake and output for at least 48 hours after general anesthesia.

Inform the patient to not let anyone draw blood, start an I.V., give an injection, or take a blood pressure on the affected side because these activities will also increase the chances of developing lymphedema.

Inspect the incision. Encourage the patient and her partner to look at her incision as soon as possible, perhaps when the first dressing is removed.

Advise the patient to ask her practitioner about reconstructive surgery or to call the local or state medical society for the names of plastic reconstructive surgeons who regularly perform surgery to create breast mounds. In many cases, reconstructive surgery may be planned before the mastectomy.

Instruct the patient about breast prostheses. The American Cancer Society’s Reach to Recovery group can provide instruction, emotional support and counseling, and a list of area stores that sell prostheses.

Give psychological and emotional support. Most patients fear cancer and possible disfigurement and worry about loss of sexual function. Explain that breast surgery doesn’t interfere with sexual function and that the patient may resume sexual activity as soon as she desires after surgery.

Also explain to the patient that she may experience phantom breast syndrome (a phenomenon in which a tingling or a pins-and-needles sensation is felt in the area of the amputated breast tissue) or depression following mastectomy. Listen to the patient’s concerns, offer support, and refer her to an appropriate organization such as the American Cancer Society’s Reach to Recovery, which offers caring and sharing groups to help breast cancer patients in the hospital and at home.

Have the patient open her hand and close it tightly six to eight times every 3 hours while she’s awake.

Elevate the arm on the affected side on a pillow above the heart level.

Encourage the patient to wash her face and comb her hair—an effective exercise.

Measure and record the circumference of the patient’s arm 2½” (5.7 cm) from her elbow. Indicate the exact place you measured. By remeasuring a month after surgery, and at intervals during and following radiation therapy, you can determine whether lymphedema is present. The patient may complain that her arm is heavy—an early symptom of lymphedema.

When the patient is home, she can elevate her arm and hand by supporting it on the back of a chair or a couch.

Malnutrition

GI obstruction

Iron deficiency anemia

Metastasis

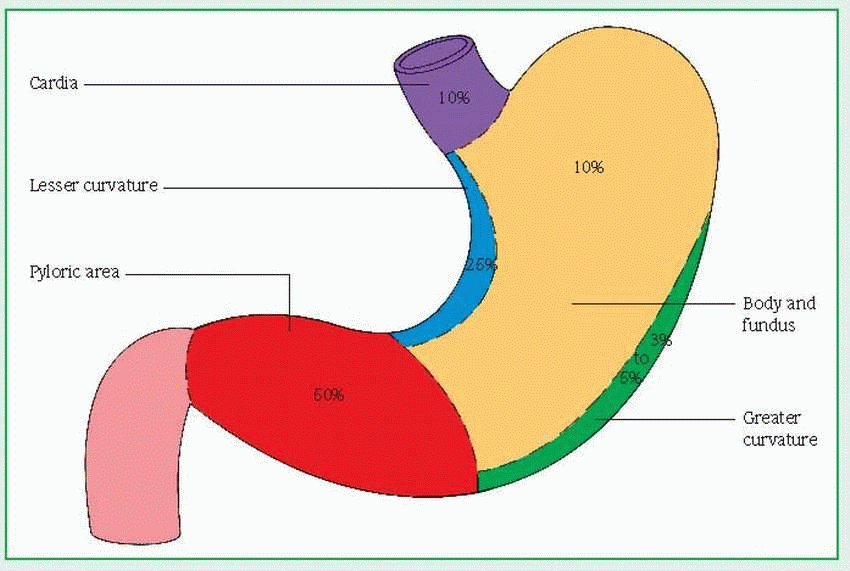

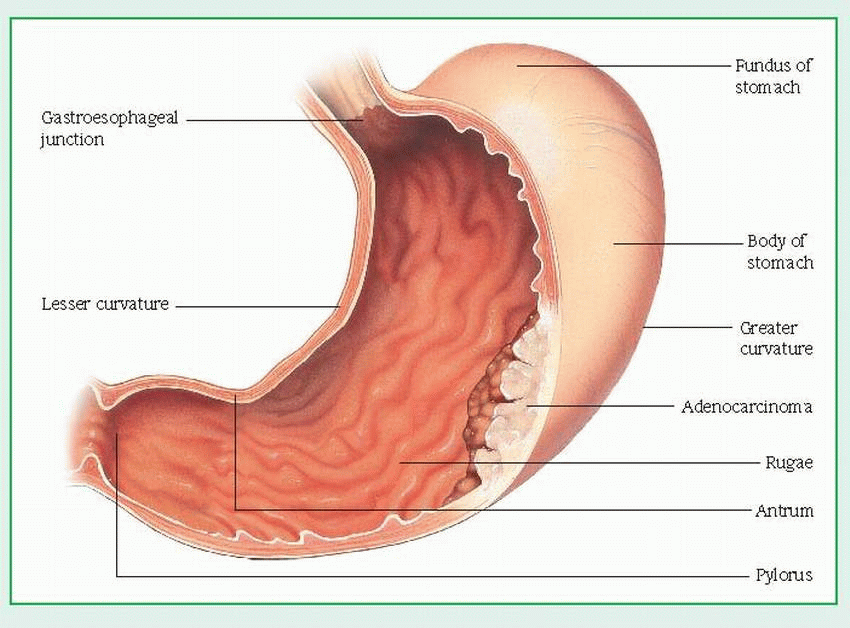

Barium X-rays of the GI tract with fluoroscopy show changes (tumor or filling defect in the outline of the stomach, loss of flexibility and dis-tensibility, and abnormal gastric mucosa with or without ulceration).

Gastroscopy with fiber-optic endoscopy helps rule out other diffuse gastric mucosal abnormalities by allowing direct visualization and gastroscopic biopsy to evaluate gastric mucosal lesions.

Photography with fiber-optic endoscope provides a permanent record of gastric lesions that can later be used to determine disease progression and effect of treatment.

A gastric acid stimulation test determines whether the stomach is able to properly secrete acid.

include gastrostomy, jejunostomy, or a gastric or partial gastric resection. Such surgery may temporarily relieve vomiting, nausea, pain, and dysphagia, while allowing enteral nutrition to continue.

Before surgery, prepare the patient for its effects and for postsurgical procedures such as insertion of a nasogastric (NG) tube for drainage and I.V. lines.

Reassure the patient who’s having a partial gastric resection that he may eventually be able to eat normally. Prepare the patient who’s having a total gastrectomy for slow recovery and only partial return to a normal diet.

Include the family in all phases of the patient’s care.

Emphasize the importance of changing position every 2 hours and of deep breathing.

After surgery, give meticulous supportive care to promote recovery and prevent complications.

After any type of gastrectomy, pulmonary complications may result, and oxygen may be needed. Regularly assist the patient with turning, coughing, and deep breathing. Turning the

patient hourly and administering analgesic opioids, as ordered, may prevent pulmonary problems. Incentive spirometry may also be needed for complete lung expansion. Proper positioning is important as well; semi-Fowler’s position facilitates breathing and drainage.

After gastrectomy, little (if any) drainage comes from the NG tube because no secretions form after stomach removal. Without a stomach for storage, many patients experience dumping syndrome. Intrinsic factor is absent from gastric secretions, leading to malabsorption of vitamin B12. To prevent vitamin B12 deficiency, the patient must take a replacement vitamin for the rest of his life as well as an iron supplement.

During radiation treatment, encourage the patient to eat high-calorie, well-balanced meals. Offer fluids such as ginger ale to minimize such radiation adverse effects as nausea and vomiting.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree