Malignant Melanoma and Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Skin

Hiram C. Polk Jr.

Motaz Qadan

An often overlooked part of mastery is elegant and specific simplification, which applies directly to most forms of skin cancer. Dramatic improvements in the early diagnosis of malignant melanoma have clearly occurred in the last 30 years. Within that, overall improvement has been a remarkable increase in genuinely early diagnosis, yielding more in situ and other very favorable forms of early invasive melanoma. The actual data regarding these changes are somewhat complex, since the majority of melanomas are diagnosed in the offices of dermatology specialists and family practitioners. Much treatment is accomplished either in the dermatologists’ office or in ambulatory surgery centers and not reported through traditional hospital-based tumor registries. The remarkable change for the better by improving early diagnosis, however, has been offset, to some degree, by a rising incidence of the disease related to increased exposure to the sun, especially as a larger portion of the North American population have moved to the Sunbelt. The broader use of tanning beds, which is largely unregulated, is another factor which undoubtedly contributes to this rise.

Information about squamous cell cancer is much less specific. Again, basic lesions are usually diagnosed in doctors’ offices. In recent decades, the traditional victim, a family farmer who has suffered sun exposure, has been altered politically and demographically to include nearly anyone. The same sun exposure that predisposes toward melanoma appears to promote the likelihood of development of squamous cell cancer, especially in the head and neck regions.

Pathogenesis

Some melanomas arise as changes in existing ordinary moles, while others appear to arise de novo. Risk factors for development of malignant melanoma are fairly well described. Particularly at risk are fair-complected people, often with blond or red hair, and who typically reside between the Tropic of Capricorn and the Tropic of Cancer, which predisposes them to heightened sun exposure and ultraviolet irradiation. A good example of the prototype high-risk population would be individuals of Celtic heritage who emigrated to Australia over 100 years ago. Another factor is the number of moles that exist in an individual patient, which may or may not be complicated by a history of sunburns. The tendency to have multiple small dark moles is frequently inherited. As such, parents of melanoma patients should be readily inspected, not only to determine what the pattern of their moles may be but also to look for new primary melanomas in an often-unsuspecting population.

Sun exposure, particularly of the blistering type, during the period of teenage hormone bursts is especially important. Although the method by which data were collected is questionable, the reference to two or more blistering sunburns during teenage years as a causative factor has found its way into the literature and is probably accurate.

In the same sense, it is commonly said that large birthmarks are innocent, including bathing trunk nevi. This assertion is clearly untrue. A high proportion of these individuals acquire invasive melanoma at multiple sites within the large nevus at a later stage. When they begin to develop in such long-standing large pigmented lesions, melanomas are virtually impossible to detect even in the most attentive patients, family members, and specialist–physicians.

Again, periods of maximum risk coincide with hormonal aberration, particularly the teenage years and pregnancy. Pregnancy, in and of itself, has been debated as predisposing to the development, or the overt clinical spread, of existing melanoma. The authors’ opinion is that pregnancy is an adverse risk factor for melanoma, and the senior author has cared for at least five women who subsequently produced soon-to-be orphans, owing to progression of their melanoma during their pregnancies. The elaboration of melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH) responsible for darkening of the nipple areolar complex in pregnant women is believed to be a factor, although this remains largely unproven. This risk factor requires some very careful thought by the treating physician, particularly related to the tendency of women at present to have their first pregnancies at a later age, which naturally diminishes the opportunity to have subsequent children. Our own recommendation is that a woman who has, or had, a melanoma thicker than 1.5 mm, and/or is ulcerated or nodular, should not become pregnant during the first 5 years after such diagnosis. These alternative factors of thickness, ulceration, and conformation supervene to indicate that pregnancy avoidance or termination becomes clinically more significant. Here lies a major test of a patient’s trust in her melanoma surgeon. Few obstetricians are aware of this unusual risk. Whether or not pregnancy itself predisposes to melanoma is less clear. However, oral contraception is well known not to predispose to melanoma.

Overt immunosuppression, either as the result of cancer chemotherapy or as agents used to suppress host responses to solid organ or bone marrow transplants, also predisposes to new or recurrent melanoma. Obviously, physicians and patients do not undertake transplant immunosuppression lightly. However, in patients with previously diagnosed and treated melanoma, increased surveillance is warranted. Also, it appears that de novo melanomas can develop more readily in this scenario. The immunosuppressed patient warrants special attention, with at least annual examinations for a variety of skin cancers that include either new or recurrent melanoma and squamous cell cancer.

The dysplastic nevus syndrome is a relatively rare phenomenon that generally consists of >100 moles, and, frequently, as many as a 1,000 on a fair-complected person. Here, the dominant pattern is a relentless conversion of these moles to invasive melanoma, again apparently accentuated by the waxing and waning of hormones during teenage years or early adulthood. The optimum surgical management of these patients is unclear, although the senior author has never been able to clear the number of lesions as rapidly as multiple primary melanoma appear to progress during the course of this illness once the first melanoma is detected.

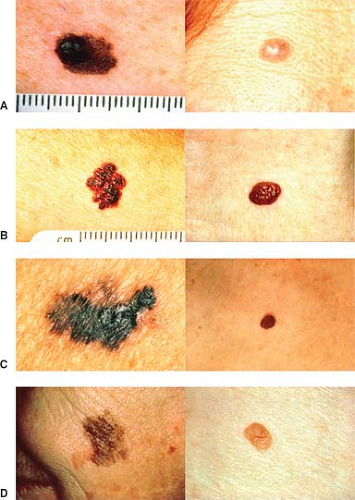

Diagnosis of melanoma has been simplified through the brilliant and imaginative work of the Queensland Melanoma Project, led by the late Professor Neville Davis. “A-B-C-D” is a simple mnemonic that can be applied by

virtually any physician or nurse practitioner to distinguish moles that possess malignant characteristics. Figure 1 demonstrates the different stages.

virtually any physician or nurse practitioner to distinguish moles that possess malignant characteristics. Figure 1 demonstrates the different stages.

Asymmetry, where one half looks dissimilar to the other half.

Irregular borders are notched margins seen to occur in some relatively large moles.

Uneven coloration is characteristic of melanoma, with parts of the lesion often being light tan to brown to black.

Finally, diameters >6 mm are more prone to be associated with melanoma and are therefore suspicious.

As simple as this concept is, it is the backbone of early diagnosis by doctors, nurses, and other healthcare professionals in highly developed countries. It can readily be applied to self-diagnosis through the distribution of simple patient education material. It should be part of the diagnosis for every melanoma, both in patients and their blood relatives.

There are two other variants of melanoma that remain difficult to diagnose. The first is the amelanotic melanoma, which is difficult to differentiate among a variety of exotic dermatologic lesions, squamous cell cancer, and local fungal infections. A high degree of suspicion may be a trite phrase, but it is virtually the only guide for any nonpigmented ulcerated skin lesion. The other variant with this special difficulty in diagnosis is the subungual melanoma that occurs commonly on the feet. Inevitably, all patients have a history of having struck their toenails; many thoughtful physicians will have made a diagnosis of subungual hematoma. The nature of the subungual melanoma, however, is indicated by its tendency to push the nail, to elevate the nail, to bleed, and to be painful. Any question about the presence of a subungual melanoma needs to be followed by deroofing of the lesion and an adequate incisional biopsy or curettage of the specimen.

The patient’s signs or symptoms in these circumstances are enormously helpful to a physician who suspects melanoma. Lesions tend to itch, bleed, and change in size or color. Any of these is significant, particularly when combined with the observational “A-B-C-D” algorithm.

Squamous cell cancers continue to be enigmas for most nondermatologists. In fact, any elevated lesion or nonhealing ulcer on the skin of a patient, particularly in a patient older than 50 years, and with sunburn, either presently or by history, warrants an excisional biopsy. In most cases, the biopsy can be a local excision with 1 to 2 mm margins, with simple repair of the wound.

Biopsy Confirmation

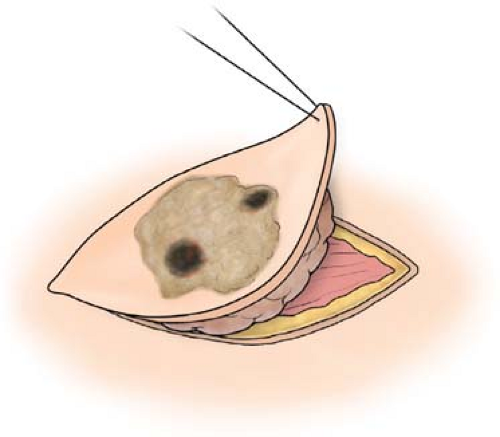

This important step has been described exhaustively, particularly for melanoma. In fact, as we have encouraged practitioners at all levels to do at the slightest provocation, “biopsy any symptomatic skin lesion!” Any form of tissue diagnosis is acceptable. Actually, we have often said that the only form of biopsy that is absolutely contraindicated is cauterization; smoke under the microscope seldom looks like melanoma. As a result, this must be avoided at all costs. In fact, any piece of a melanoma that helps make the diagnosis is helpful. By accepting imperfect diagnoses, one at the same time promotes an earlier biopsy on the part of practitioners, who, either by training or geographic location, do not have access to broader surgical skills. A shave biopsy, in our opinion, is absolutely acceptable. The preferred biopsy, however, unless the lesion is very large, is a local excision with 1 to 2 mm margins, which will effectively deal with the occasional benign pigmented seborrheic keratosis, and, at the same time, provide an accurate depth of melanoma and cell type, if it is present. In other words, this should extend just into the full thickness end of the subcutaneous fat (Fig. 2). In part, because of the progressively earlier diagnosis of melanocytic lesions, errors of omission have begun to occur. It is sobering to recognize that nearly 2% of melanomas are not called such. To some degree, the clinician can override such a potential effect by simply re-excising (1 to 2 mm margins) any suspicious or ambiguous lesions locally, and subsequently asking for a second, or even third, pathologic opinion. The minimal increase in scar or scarring is more than offset by improved accuracy of pathologic diagnosis.

If the lesion is large, or located on the face, one may opt to excise a simple 1 to 2 mm pie-shaped wedge from the edge of the lesion, choosing whichever edge by palpation is the more highly elevated. In fact, any ulcerated and/or elevated nonhealing skin lesion is at risk of being a malignant

melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or basal cell carcinoma, and it is properly treated with a 1 to 2 mm margin of excision. Depending on the location, once again, it is closed using simple suture with reconstructive methods used only where necessary.

melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or basal cell carcinoma, and it is properly treated with a 1 to 2 mm margin of excision. Depending on the location, once again, it is closed using simple suture with reconstructive methods used only where necessary.

Melanoma Thickness

The initial observations by Clark and associates suggested that the depth of invasion of melanoma down to the skin and even into the subcutaneous tissues was important prognostically. This observation was given much sharper focus by the work of Breslow, who simply quantified the depth of invasion, not by the various layers of the skin but by the depth of maximum melanoma invasion in millimeters. This latter figure is regularly interpreted accurately and has nearly a one-to-one relationship with prognosis. Prognostically, it is well known that melanomas <0.75 mm thick approach 99% cure rates with long-term survival. The senior author has only seen 2 of >1,000 such cases metastasize without explanation, even upon reexamination of the original specimen.

As the extent of tumor invasion progressively deepens, sentinel lymph node assessment becomes necessary. The margin of excision increases as do both the depth of excision and the need for continuous close observation. One of the hallmark characteristics of malignant melanoma, as a disease with which to deal, is its readily documented propensity for invasion with justification for additional adjunctive therapy.

The treatment of malignant melanoma focuses upon adequate local excision. In fact, this is true for most forms of cancer, but is especially important here. To some degree, this has been fairly well defined as needing 1 cm of peripheral margin around the pigmented lesion for every invasion of 1 mm depth, unless the lesion is large, located on the face, or very thick, when common sense permits modification of that dictum. Proceeding via an elliptical incision in the line of skin creases allows for a generous wide local excision of the primary tumor and simple expansion of the resected margins as required. The elliptical wound permits simple wound closure, with or without flaps, and cosmetic defects are kept to a minimum when the wound is closed in line with skin creases. Skin grafts are seldom required now, unless lesions are in functionally important areas such as the hand, the ankle, and around the elbow.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree