Rupture of the appendix causes sudden cessation of pain. Then, signs and symptoms of peritonitis develop, such as severe abdominal pain, pallor, hypoactive or absent bowel sounds, diaphoresis, and a high fever.

Special Considerations

Draw blood for laboratory tests such as a complete blood count, including a white blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and blood cultures, and prepare the patient for abdominal X-rays to confirm appendicitis. Make sure that the patient receives nothing by mouth, and expect to prepare the patient for an appendectomy. Administration of a cathartic or an enema may cause the appendix to rupture and should be avoided.

Patient Counseling

Explain which postoperative signs and symptoms the patient should report. Instruct the patient on wound care and explain any needed activity restrictions.

EXAMINATION TIP Eliciting McBurney’s Sign

EXAMINATION TIP Eliciting McBurney’s Sign

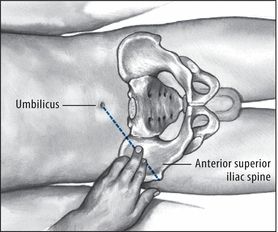

To elicit McBurney’s sign, help the patient into a supine position, with his knees slightly flexed and his abdominal muscles relaxed. Then, palpate deeply and slowly in the right lower quadrant over McBurney’s point — located about 2″ (5 cm) from the right anterior superior spine of the ilium, on a line between the spine and the umbilicus. Point pain and tenderness, a positive McBurney’s sign, indicates appendicitis.

Pediatric Pointers

McBurney’s sign is also elicited in children with appendicitis.

Geriatric Pointers

In elderly patients, McBurney’s sign (as well as other peritoneal signs) may be decreased or absent.

REFERENCES

Ilves, I., Paajanen, H. E., Herzig, K. H., Fagerstrom, A., & Miettinen, P. J. (2011). Changing incidence of acute appendicitis and nonspecific abdominal pain between 1987 and 2007 in Finland. World Journal of Surgery, 35(4), 731–738.

Wilms, I. M., De Hoog, D. E., De Visser, D. C., & Janzing, H. M. (2011). Appendectomy versus antibiotic treatment for acute appendicitis. Cochrane Database Systematic Review, 9(11), CD008359.

McMurray’s Sign

Commonly an indicator of medial meniscal injury, McMurray’s sign is a palpable, audible click or pop elicited by rotating the tibia on the femur. It results when gentle manipulation of the leg traps torn cartilage and then lets it snap free. Because eliciting this sign forces the surface of the tibial plateau against the femoral condyles, such manipulation is contraindicated in patients with suspected fractures of the tibial plateau or femoral condyles.

A positive McMurray’s sign augments other findings commonly associated with meniscal injury, such as severe joint line tenderness, locking or clicking of the joint, and a decreased range of motion (ROM).

History and Physical Examination

After McMurray’s sign has been elicited, find out if the patient is experiencing acute knee pain. Then ask him to describe a recent knee injury. For example, did his injury place twisting external or internal force on the knee, or did he experience blunt knee trauma from a fall? Also, ask about previous knee injury, surgery, prosthetic replacement, or other joint problems, such as arthritis, that could have weakened the knee. Ask if anything aggravates or relieves the pain and if he needs assistance to walk.

Have the patient point to the exact area of pain. Assess the leg’s ROM, both passive and with resistance. Next, check for cruciate ligament stability by noting anterior or posterior movement of the tibia on the femur (drawer sign). Finally, measure the quadriceps muscles in both legs for symmetry. (See Eliciting McMurray’s Sign.)

EXAMINATION TIP Eliciting McMurray’s Sign

EXAMINATION TIP Eliciting McMurray’s Sign

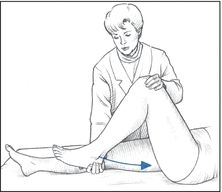

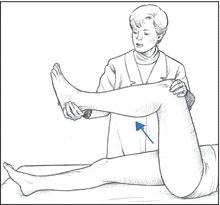

Eliciting McMurray’s sign requires special training and gentle manipulation of the patient’s leg to avoid extending a meniscal tear or locking the knee. If you’ve been trained to elicit McMurray’s sign, place the patient in a supine position and flex his affected knee until his heel nearly touches his buttock. Place your thumb and index finger on either side of the knee joint space and grasp his heel with your other hand. Then rotate the foot and lower leg laterally to test the posterior aspect of the medial meniscus.

Keeping the patient’s foot in a lateral position, extend the knee to a 90-degree angle to test the anterior aspect of the medial meniscus. A palpable or audible click — a positive McMurray’s sign — indicates injury to meniscal structures.

Medical Causes

- Meniscal tear. McMurray’s sign can usually be elicited with a meniscal tear injury. Associated signs and symptoms include acute knee pain at the medial or lateral joint line (depending on injury site) and decreased ROM or locking of the knee joint. Quadriceps weakening and atrophy may also occur.

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for knee X-rays, arthroscopy, and arthrography, and obtain any previous X-rays for comparison. If trauma precipitated the knee pain and McMurray’s sign, an effusion or hemarthrosis may occur. Prepare the patient for aspiration of the joint. Immobilize and apply ice to the knee, and apply a cast or a knee immobilizer.

Patient Counseling

Explain the purpose of elevating the affected leg, the proper use of any required assistive devices, and the proper use of analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs. Teach knee exercises and discuss any lifestyle changes the patient should make.

Pediatric Pointers

McMurray’s sign in adolescents is usually elicited in a meniscal tear caused by a sports injury. It may also be elicited in children with congenital discoid meniscus.

REFERENCES

Amorim, J. A., Remigio, D. S., Damazio Filho, O., Barros, M. A., Carvalho, V. N., & Valenca, M. M. (2010). Intracranial subdural hematoma post-spinal anesthesia: Report of two cases and review of 33 cases in the literature. Brazilian Journal of Anesthesiology, 60, 620–629.

Machurot, P. Y., Vergnion, M., Fraipont, V., Bonhomme, V., & Damas, F. (2010). Intracranial subdural hematoma following spinal anesthesia: Case report and review of the literature. Acta Anaesthesiology Belgium, 61, 63–66.

Melena

A common sign of upper GI bleeding, melena is the passage of black, tarry stools containing digested blood. The characteristic color results from bacterial degradation and hydrochloric acid acting on the blood as it travels through the GI tract. At least 60 mL of blood is needed to produce this sign. (See Comparing Melena to Hematochezia.)

Severe melena can signal acute bleeding and life-threatening hypovolemic shock. Usually, melena indicates bleeding from the esophagus, stomach, or duodenum, although it can also indicate bleeding from the jejunum, ileum, or ascending colon. This sign can also result from swallowing blood, as in epistaxis; from taking certain drugs; or from ingesting alcohol. Because false melena may be caused by ingestion of lead, iron, bismuth, or licorice (which produces black stools without the presence of blood), all black stools should be tested for occult blood.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If the patient is experiencing severe melena, quickly take his orthostatic vital signs to detect hypovolemic shock. A decline of 10 mm Hg or more in systolic pressure or an increase of 10 beats/minute or more in the pulse rate indicates volume depletion. Quickly examine the patient for other signs of shock, such as tachycardia, tachypnea, and cool, clammy skin. Insert a large-bore I.V. line to administer replacement fluids and allow for blood transfusion. Obtain hematocrit, prothrombin time, International Normalized Ratio, and partial thromboplastin time. Place the patient flat with his head turned to the side and his feet elevated. Administer supplemental oxygen as needed.

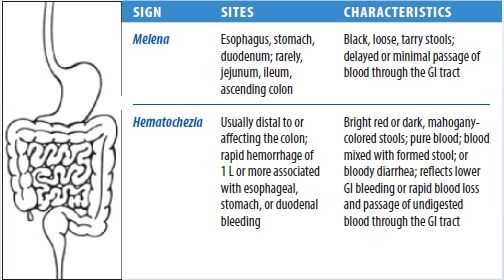

Comparing Melena to Hematochezia

With GI bleeding, the site, amount, and rate of blood flow through the GI tract determine if a patient will develop melena (black, tarry stools) or hematochezia (bright red, bloody stools). Usually, melena indicates upper GI bleeding, and hematochezia indicates lower GI bleeding. However, with some disorders, melena may alternate with hematochezia. This chart helps differentiate these two commonly related signs.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient’s condition permits, ask when he discovered his stools were black and tarry. Ask about the frequency and quantity of bowel movements. Has he had melena before? Ask about other signs and symptoms, notably hematemesis or hematochezia, and about use of anti-inflammatories, alcohol, or other GI irritants. Also, find out if he has a history of GI lesions. Ask if the patient takes iron supplements, which may also cause black stools. Obtain a drug history, noting the use of warfarin or other prescribed and herbal anticoagulants.

Next, inspect the patient’s mouth and nasopharynx for evidence of bleeding. Perform an abdominal examination that includes auscultation, palpation, and percussion.

Medical Causes

- Colon cancer. On the right side of the colon, early tumor growth may cause melena accompanied by abdominal aching, pressure, or cramps. As the disease progresses, the patient develops weakness, fatigue, and anemia. Eventually, he also experiences diarrhea or obstipation, anorexia, weight loss, vomiting, and other signs and symptoms of intestinal obstruction.

With a tumor on the left side, melena is a rare sign until late in the disease. Early tumor growth commonly causes rectal bleeding with intermittent abdominal fullness or cramping and rectal pressure. As the disease progresses, the patient may develop obstipation, diarrhea, or pencil-shaped stools. At this stage, bleeding from the colon is signaled by melena or bloody stools.

- Ebola virus. Melena, hematemesis, and bleeding from the nose, gums, and vagina may occur later with Ebola virus. Patients usually report an abrupt onset of a headache, malaise, myalgia, a high fever, diarrhea, abdominal pain, dehydration, and lethargy on the fifth day of illness. Pleuritic chest pain, a dry hacking cough, and pharyngitis have also been noted. A maculopapular rash develops between days 5 and 7 of the illness.

- Esophageal cancer. Melena is a late sign of esophageal cancer, a malignant neoplastic disease that’s three times more common in men than in women. Increasing obstruction first produces painless dysphagia, then rapid weight loss. The patient may experience steady chest pain with substernal fullness, nausea, vomiting, and hematemesis. Other findings include hoarseness, a persistent cough (possibly hemoptysis), hiccups, a sore throat, and halitosis. In the later stages, signs and symptoms include painful dysphagia, anorexia, and regurgitation.

- Esophageal varices (ruptured). Ruptured esophageal varices are a life-threatening disorder that can produce melena, hematochezia, and hematemesis. Melena is preceded by signs of shock, such as tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension, and cool, clammy skin. Agitation or confusion signals developing hepatic encephalopathy.

- Gastritis. Melena and hematemesis are common. The patient may also experience mild epigastric or abdominal discomfort that’s exacerbated by eating, belching, nausea, vomiting, and malaise.

- Mallory-Weiss syndrome. Mallory-Weiss syndrome is characterized by massive bleeding from the upper GI tract due to a tear in the mucous membrane of the esophagus or the junction of the esophagus and the stomach. Melena and hematemesis follow vomiting. Severe upper abdominal bleeding leads to signs and symptoms of shock, such as tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension, and cool, clammy skin. The patient may also report epigastric or back pain.

- Mesenteric vascular occlusion. Mesenteric vascular occlusion is a life-threatening disorder that produces slight melena with 2 to 3 days of persistent, mild abdominal pain. Later, abdominal pain becomes severe and may be accompanied by tenderness, distention, guarding, and rigidity. The patient may also experience anorexia, vomiting, a fever, and profound shock.

- Peptic ulcer. Melena may signal life-threatening hemorrhage from vascular penetration. The patient may also develop decreased appetite, nausea, vomiting, hematemesis, hematochezia, and left epigastric pain that’s gnawing, burning, or sharp and may be described as heartburn or indigestion. With hypovolemic shock come tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension, dizziness, syncope, and cool, clammy skin.

- Small-bowel tumors. Small-bowel tumors may bleed and produce melena. Other signs and symptoms include abdominal pain, distention, and an increasing frequency and pitch of bowel sounds.

- Thrombocytopenia. Melena or hematochezia may accompany other manifestations of bleeding tendency: hematemesis, epistaxis, petechiae, ecchymoses, hematuria, vaginal bleeding, and characteristic blood-filled oral bullae. Typically, the patient displays malaise, fatigue, weakness, and lethargy.

- Typhoid fever. Melena or hematochezia occurs late in typhoid fever and may occur with hypotension and hypothermia. Other late findings include mental dullness or delirium, marked abdominal distention and diarrhea, marked weight loss, and profound fatigue.

- Yellow fever. Melena, hematochezia, and hematemesis are ominous signs of hemorrhage, a classic feature, which occurs along with jaundice. Other findings include a fever, a headache, nausea, vomiting, epistaxis, albuminuria, petechiae and mucosal hemorrhage, and dizziness.

Other Causes

- Drugs and alcohol. Aspirin, other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or alcohol can cause melena as a result of gastric irritation.

Special Considerations

Monitor the patient’s vital signs, and look closely for signs of hypovolemic shock. For general comfort, encourage bed rest, and keep the patient’s perianal area clean and dry to prevent skin irritation and breakdown. A nasogastric tube may be necessary to assist with drainage of gastric contents and decompression. Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, including blood studies, gastroscopy or other endoscopic studies, barium swallow, and upper GI series, and for blood transfusions as indicated by his hematocrit.

Patient Counseling

Explain any bowel elimination changes the patient should report and the need to avoid aspirin, other NSAIDs, and alcohol. Stress the importance of undergoing colorectal cancer screening.

Pediatric Pointers

Neonates may experience melena neonatorum due to extravasation of blood into the alimentary canal. In older children, melena usually results from a peptic ulcer, gastritis, or Meckel’s diverticulum.

Geriatric Pointers

In elderly patients with recurrent intermittent GI bleeding without a clear etiology, angiography or exploratory laparotomy should be considered when the risk of continued anemia is deemed to outweigh the risk associated with the procedures.

REFERENCES

Miheller, P., Kiss, L. S., Juhasz, M., Mandel, M., & Lakatos, P. L. (2013). Recommendations for identifying Crohn’s disease patients with poor prognosis. Expert Review Clinical Immunology, 9, 65–76.

Pariente, B., Cosnes, J., Danese, S., Sandborn, W. J., Lewin, M., Fletcher, J. G., … Lémann, M. (2011). Development of the Crohn’s disease digestive damage score, the Lémann score. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, 17(6), 1415–1422.

Menorrhagia

(See Also Metrorrhagia)

Abnormally heavy or long menstrual bleeding, menorrhagia may occur as a single episode or a chronic sign. In menorrhagia, bleeding is heavier than the patient’s normal menstrual flow; menstrual blood loss is 80 mL or more per monthly period. A form of dysfunctional uterine bleeding, menorrhagia can result from endocrine and hematologic disorders, stress, and certain drugs and procedures.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

Evaluate the patient’s hemodynamic status by taking orthostatic vital signs. Insert a large-gauge I.V. line to begin fluid replacement if the patient shows an increase of 10 beats/minute in pulse rate, a decrease of 10 mm Hg in systolic blood pressure, or other signs of hypovolemic shock, such as pallor, tachycardia, tachypnea, and cool, clammy skin. Place the patient in a supine position with her feet elevated, and administer supplemental oxygen as needed.

Use menstrual pads to obtain information related to the quality and quantity of bleeding. Then prepare the patient for a pelvic examination to help determine the cause of bleeding.

History and Physical Examination

When the patient’s condition permits, obtain a history. Determine her age at menarche, the duration of menstrual periods, and the interval between them. Establish the date of the patient’s last menses, and ask about recent changes in her normal menstrual pattern. Have the patient describe the character and amount of bleeding. For example, how many pads or tampons does the patient use? Has she noted clots or tissue in the blood? Also ask about the development of other signs and symptoms before and during her period.

Next, ask if the patient is sexually active. Does she use a method of birth control? If so, what kind? Could the patient be pregnant? Be sure to note the number of pregnancies, the outcome of each, and any pregnancy-related complications. Find out the dates of her most recent pelvic examination and Papanicolaou smear and the details of any previous gynecologic infections or neoplasms. Also, be sure to ask about previous episodes of abnormal bleeding and the outcome of treatment. If possible, obtain a pregnancy history of the patient’s mother, and determine if the patient was exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol. (This drug has been linked to vaginal adenosis.)

Be sure to ask the patient about her general health and medical history. Note particularly if the patient or her family has a history of thyroid, adrenal, or hepatic disease; blood dyscrasias; or tuberculosis because these may predispose the patient to menorrhagia. Also, ask about the patient’s past surgical procedures and recent emotional stress. Find out if the patient has undergone X-ray or other radiation therapy, because this may indicate prior treatment for menorrhagia. Obtain a thorough drug and alcohol history, noting the use of anticoagulants or aspirin. Perform a pelvic examination, and obtain blood and urine samples for pregnancy testing.

Medical Causes

- Blood dyscrasias. Blood dyscrasias is a general term that refers to any abnormal components within the blood cells or their essential elements that control bleeding. Menorrhagia is one of several possible signs of a bleeding disorder. Other possible associated findings include epistaxis, bleeding gums, purpura, hematemesis, hematuria, and melena.

- Hypothyroidism. Menorrhagia is a common early sign and is accompanied by such nonspecific findings as fatigue, cold intolerance, constipation, and weight gain despite anorexia. As hypothyroidism progresses, intellectual and motor activity decrease; the skin becomes dry, pale, cool, and doughy; the hair becomes dry and sparse; and the nails become thick and brittle. Myalgia, hoarseness, a decreased libido, and infertility commonly occur. Eventually, the patient develops a characteristic dull, expressionless face and edema of the face, hands, and feet.

Also, deep tendon reflexes are delayed, and bradycardia and abdominal distention may occur.

- Uterine fibroids. Menorrhagia is the most common sign, but other forms of abnormal uterine bleeding as well as dysmenorrhea or leukorrhea can also occur. Possible related findings include abdominal pain, a feeling of abdominal heaviness, a backache, constipation, urinary urgency or frequency, and an enlarged uterus, which is usually nontender.

Other Causes

- Drugs. The use of a hormonal contraceptive may cause a sudden onset of profuse, prolonged menorrhagia. Anticoagulants have also been associated with excessive menstrual flow. Injectable or implanted contraceptives may cause menorrhagia in some women.

HERB ALERT

HERB ALERT

Herbal remedies, such as ginseng, can cause postmenopausal bleeding.

- Intrauterine devices. Menorrhagia can result from the use of intrauterine contraceptive devices.

Special Considerations

Continue to monitor the patient closely for signs of hypovolemia. Encourage her to maintain an adequate fluid intake. Monitor her intake and output, and estimate uterine blood loss by recording the number of sanitary napkins or tampons used during an abnormal period and comparing this with usage during a normal period. To help decrease blood flow, encourage the patient to rest and to avoid strenuous activities. Obtain blood samples for hematocrit, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and international normalized ratio levels.

Patient Counseling

Explain all procedures and treatments to the patient and teach her which signs and symptoms require immediate medical attention. Discuss the need to rest and to avoid strenuous activities until bleeding subsides.

Pediatric Pointers

Irregular menstrual function in young girls may be accompanied by hemorrhage and resulting anemia.

Geriatric Pointers

In postmenopausal women, menorrhagia can’t occur. In such patients, vaginal bleeding is usually caused by endometrial atrophy. Malignancy must be ruled out.

REFERENCES

Farage, M. A., Neill, S., & MacLean, A. B. (2009). Physiological changes associated with the menstrual cycle. Obstetrics and Gynecology Survey, 64, 58–72.

Mitchell, S. C., Smith, R. L., & Waring, R. H. (2009). The menstrual cycle and drug metabolism. Current Drug Metabolism, 10, 499–507.

Metrorrhagia

(See Also Menorrhagia)

Metrorrhagia — uterine bleeding that occurs irregularly between menstrual periods — is usually light, although it can range from staining to hemorrhage. Usually, this common sign reflects slight physiologic bleeding from the endometrium during ovulation. However, metrorrhagia may be the only indication of an underlying gynecologic disorder and can also result from stress, drugs, treatments, and intrauterine devices.

History and Physical Examination

Begin your evaluation by obtaining a thorough menstrual history. Ask the patient when she began menstruating and about the duration of menstrual periods, the interval between them, and the average number of tampons or pads she uses. When does metrorrhagia usually occur in relation to her period? Does she experience other signs or symptoms? Find out the date of her last menses, and ask about other recent changes in her normal menstrual pattern. Get details of previous gynecologic problems. If applicable, obtain a contraceptive and obstetric history. Record the dates of her last Papanicolaou smear and pelvic examination. Ask the patient when she last had sex and whether or not it was protected. Next, ask about her general health and any recent changes. Is she under emotional stress? If possible, obtain a pregnancy history of the patient’s mother. Was the patient exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol? (This drug has been linked to vaginal adenosis.)

Perform a pelvic examination if indicated, and obtain blood and urine samples for pregnancy testing.

Medical Causes

- Cervicitis. Cervicitis is a nonspecific infection that may cause spontaneous bleeding, spotting, or posttraumatic bleeding. Assessment reveals red, granular, irregular lesions on the external cervix. Purulent vaginal discharge (with or without odor), lower abdominal pain, and a fever may occur.

- Dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Abnormal uterine bleeding not caused by pregnancy or major gynecologic disorders usually occurs as metrorrhagia, although menorrhagia is possible. Bleeding may be profuse or scant, intermittent or constant.

- Endometrial polyps. In most patients, endometrial polyps cause abnormal bleeding, usually intermenstrual or postmenopausal; however, some patients do remain asymptomatic.

- Endometriosis. Metrorrhagia (usually premenstrual) may be the only indication of endometriosis or it may accompany cyclical pelvic discomfort, infertility, and dyspareunia. A tender, fixed adnexal mass may be palpable on bimanual examination.

- Endometritis. Endometritis causes metrorrhagia, purulent vaginal discharge, and enlargement of the uterus. It also produces a fever, lower abdominal pain, and abdominal muscle spasm.

- Gynecologic cancer. Metrorrhagia is commonly an early sign of cervical or uterine cancer. Later, the patient may experience weight loss, pelvic pain, fatigue and, possibly, an abdominal mass.

- Uterine leiomyomas. Besides metrorrhagia, uterine leiomyomas may cause increasing abdominal girth and heaviness in the abdomen, constipation, and urinary frequency or urgency. The patient may report pain if the uterus attempts to expel the tumor through contractions and if the tumors twist or necrose after circulatory occlusion or infection, but the patient with leiomyomas is usually asymptomatic.

- Vaginal adenosis. Vaginal adenosis commonly produces metrorrhagia. Palpation reveals roughening or nodules in affected vaginal areas.

Other Causes

- Drugs. Anticoagulants and oral, injectable, or implanted contraceptives may cause metrorrhagia.

HERB ALERT

HERB ALERT

Herbal remedies, such as ginseng, can cause postmenopausal bleeding.

- Surgery and procedures. Cervical conization and cauterization may cause metrorrhagia.

Special Considerations

Encourage bed rest to reduce bleeding. Give an analgesic for discomfort.

Patient Counseling

Explain all procedures, treatments, and signs and symptoms that require immediate attention. Discuss the importance of regular gynecologic examinations and Pap smears.

REFERENCES

Brosens, I., & Benagiano, G. (2013). Is neonatal uterine bleeding involved in the pathogenesis of endometriosis as a source of stem cells? Fertility and Sterility, doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.04.046

Brosens, I., Gordts, S., & Benagiano, G. (2013). Endometriosis in adolescents is a hidden, progressive and severe disease that deserves attention, not just compassion. Human Reproduction, 28, 2016–2031.

Miosis

Miosis — pupillary constriction caused by contraction of the sphincter muscle in the iris — occurs normally as a response to increased light, or administration of a miotic; as part of the eye’s accommodation reflex; and as part of the aging process (pupil size steadily decreases from adolescence to about age 60). However, it can also stem from an ocular or neurologic disorder, trauma, or use of a systemic drug. A rare form of miosis — Argyll Robertson pupil — can stem from tabes dorsalis and diverse neurologic disorders. Occurring bilaterally, these miotic (often pinpoint), unequal, and irregularly shaped pupils don’t dilate properly with mydriatic use and fail to react to light, although they do constrict on accommodation.

History and Physical Examination

Begin by asking the patient if he has experienced other ocular symptoms, and have him describe their onset, duration, and intensity. During your history, be sure to ask about trauma, serious systemic disease, and the use of topical and systemic drugs.

Next, perform a thorough eye examination. Test visual acuity in each eye, with and without correction, paying particular attention to blurred or decreased vision in the miotic eye. Examine and compare the pupils for size (many people have a small normal discrepancy), color, shape, reaction to light, accommodation, and consensual light response. Examine the eyes for additional signs, and then evaluate extraocular muscle function by assessing the six cardinal fields of gaze.

Medical Causes

- Cerebrovascular arteriosclerosis. Miosis is usually unilateral, depending on the site and extent of vascular damage. Other findings include visual blurring, slurred speech or possibly aphasia, loss of muscle tone, memory loss, vertigo, and a headache.

- Cluster headache. Ipsilateral miosis, tearing, conjunctival injection, and ptosis commonly accompany a severe cluster headache, along with facial flushing and sweating, bradycardia, restlessness, and nasal stuffiness or rhinorrhea.

- Corneal foreign body. Miosis in the affected eye occurs with pain, a foreign body sensation, slight vision loss, conjunctival injection, photophobia, and profuse tearing.

- Corneal ulcer. Miosis in the affected eye appears with moderate pain, visual blurring and possibly some vision loss, and diffuse conjunctival injection.

- Horner’s syndrome. Moderate miosis is common in Horner’s syndrome, a neurologic syndrome, and occurs ipsilaterally to the spinal cord lesion. Related ipsilateral findings include a sluggish pupillary reflex, slight enophthalmos, moderate ptosis, facial anhidrosis, transient conjunctival injection, and a vascular headache. When the syndrome is congenital, the iris on the affected side may appear lighter.

- Hyphema. Usually the result of blunt trauma, hyphema can cause miosis with moderate pain, visual blurring, diffuse conjunctival injection, and slight eyelid swelling. The eyeball may feel harder than normal.

- Iritis (acute). Miosis typically occurs in the affected eye along with decreased pupillary reflex, severe eye pain, photophobia, visual blurring, conjunctival injection and, possibly, pus accumulation in the anterior chamber. The eye appears cloudy, the iris bulges, and the pupil is constricted on ophthalmic examination.

- Neuropathy. Two forms of neuropathy occasionally produce Argyll Robertson pupils. With diabetic neuropathy, related effects include paresthesia and other sensory disturbances, extremity pain, orthostatic hypotension, impotence, incontinence, and leg muscle weakness and atrophy.

With alcoholic neuropathy, related effects include progressive, variable muscle weakness and wasting; various sensory disturbances; and hypoactive deep tendon reflexes.

- Parry-Romberg syndrome. Parry-Romberg syndrome is a facial hemiatrophy that typically produces miosis, sluggish pupillary reflexes, enophthalmos, nystagmus, ptosis, and different-colored irises.

- Pontine hemorrhage. Bilateral miosis is characteristic, along with a rapid onset of coma, total paralysis, decerebrate posture, an absent doll’s eye sign, and a positive Babinski’s sign.

- Uveitis. Anterior uveitis commonly produces miosis in the affected eye, moderate to severe eye pain, severe conjunctival injection, photophobia, and occasionally pus in the anterior chamber.

With posterior uveitis, miosis is accompanied by a gradual onset of eye pain, photophobia, visual floaters, visual blurring, conjunctival injection and, commonly, a distorted pupil shape.

Other Causes

- Chemical burns. An opaque cornea may make miosis hard to detect. However, chemical burns may also cause moderate to severe pain, diffuse conjunctival injection, an inability to keep the eye open, visual blurring, and blistering.

- Drugs. Such topical drugs as acetylcholine, carbachol, demecarium bromide, echothiophate iodide, and pilocarpine are used to treat eye disorders specifically for their miotic effect. Such systemic drugs as barbiturates, cholinergics, anticholinesterases, clonidine (overdose), guanethidine monosulfate, opiates, and reserpine also cause miosis, as does deep anesthesia.

Special Considerations

Because an ocular abnormality can be a source of fear and anxiety, reassure and support the patient. Clearly explain the diagnostic tests ordered, which may include a complete ophthalmologic examination or a neurologic workup.

Patient Counseling

Demonstrate how to correctly instill eye drops. Explain measures to relieve eye pain or discomfort.

Pediatric Pointers

Miosis is common in neonates, simply because they’re asleep or sleepy most of the time. Bilateral miosis occurs with congenital microcoria, an uncommon bilateral disease transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait and marked by the absence of the dilator muscle of the pupil. At birth, these infants have pupils less than 2 mm and seem to gaze far away.

REFERENCES

Dexl, A. K., Seyeddain, O., Riha, W., Hohensinn, M., Hitzl, W., & Grabner, G. (2011). Reading performance after implantation of a small-aperture corneal inlay for the surgical correction of presbyopia: Two-year follow-up. Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery, 37(3), 525–531.

Epstein, R. L., & Gurgos, M. A. (2009). Presbyopia treatment by monocular peripheral presbyLASIK. Journal of Refractive Surgery, 25(6), 516–523.

Gerstenblith, A. T., & Rabinowitz, M. P. (2012). The wills eye manual. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Huang, J. J., & Gaudio, P. A. (2010). Ocular inflammatory disease and uveitis manual: Diagnosis and treatment. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Roy, F. H. (2012). Ocular differential diagnosis. Clayton, Panama: Jaypee–Highlights Medical Publishers, Inc.

Mouth Lesions

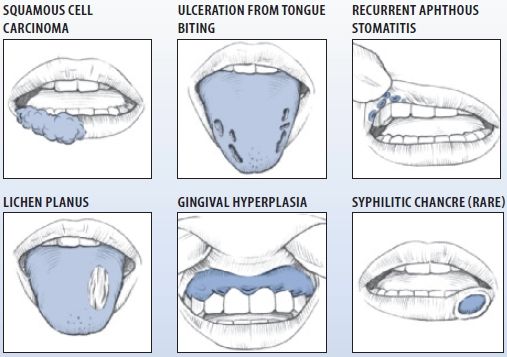

Mouth lesions include ulcers (the most common type), cysts, firm nodules, hemorrhagic lesions, papules, vesicles, bullae, and erythematous lesions. They may occur anywhere on the lips, cheeks, hard and soft palate, salivary glands, tongue, gingivae, or mucous membranes. Many are painful and can be readily detected. Some, however, are asymptomatic; when they occur deep in the mouth, they may be discovered only through a complete oral examination. (See Common Mouth Lesions, page 468.)

Mouth lesions can result from trauma, infection, systemic disease, drug use, or radiation therapy.

History and Physical Examination

Begin your evaluation with a thorough history. Ask the patient when the lesions appeared and whether he has noticed pain, odor, or drainage. Also ask about associated complaints, particularly skin lesions. Obtain a complete drug history, including food and drug allergies and antibiotic use, and a complete medical history. Note especially malignancy, sexually transmitted disease, I.V. drug use, recent infection, or trauma. Ask about his dental history, including oral hygiene habits, the frequency of dental examinations, and the date of his most recent dental visit.

Next, perform a complete oral examination, noting lesion sites and character. Examine the patient’s lips for color and texture. Inspect and palpate the buccal mucosa and tongue for color, texture, and contour; note especially painless ulcers on the sides or base of the tongue. Hold the tongue with a piece of gauze, lift it, and examine its underside and the floor of the mouth. Depress the tongue with a tongue blade, and examine the oropharynx. Inspect the teeth and gums, noting missing, broken, or discolored teeth; dental caries; excessive debris; and bleeding, inflamed, swollen, or discolored gums.

Common Mouth Lesions

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree