Lung, Mediastinum, and Pleura

Ilyssa O. Gordon

Aliya N. Husain

Introduction: Lung Frozen Section

Frozen sections of pulmonary specimens are commonly received for assessment of nodules or to determine the presence of an infectious process in immunocompromised hosts. Rarely, intraoperative evaluation in the transplant setting of a small nodule or an enlarged lymph node found in a donor lung may be requested. Frozen sections on tissue with suspected interstitial lung disease are not useful due to the small amount of tissue obtained and the freezing artifact distortion. Rare exceptions may include acute exacerbations of undiagnosed interstitial lung disease in patients who are in the intensive care unit and for whom an urgent diagnosis is needed to direct clinical decision making. In these cases, consultation with the clinical team, and consideration of a 4- to 6-hour rapid processing, if available, may be preferable.

Solitary lung nodules are the most common lung specimen submitted for intraoperative evaluation. They are typically preceded by preoperative radiologic evaluation, a key component in the diagnostic pathway. With the goal of obtaining a tissue diagnosis prior to definitive surgery, radiologic evidence of a nodule greater than 2 cm would lead to a preoperative transbronchial biopsy by flexible bronchoscopy or a CT-guided transthoracic needle core biopsy. Tissue obtained from these procedures is submitted for permanent sections as well as for more immediate cytologic evaluation. Frozen section does not typically have a role in this setting. A nodule smaller than 2 cm or a surgically inaccessible nodule would lead to an intraoperative endobronchial biopsy by rigid bronchoscopy or to a wedge biopsy, most often by video-assisted thoracoscopy (VATS). Frozen section evaluation of these tissues would aid in the determination of whether definitive surgery, namely a lobectomy and lymph node dissection, should be undertaken during the same operation. When completion lobectomies are performed, frozen section determination of bronchial margin involvement is also common. Central lung nodules are considered surgically unresectable when they involve the carina, as seen radiologically, and therefore,

frozen section diagnosis is not necessary. However, tissue may be sent to determine if it is adequate for diagnosis. Radiologically suspicious lymph nodes are also an important component of the staging workup and are discussed further in the mediastinum section.

frozen section diagnosis is not necessary. However, tissue may be sent to determine if it is adequate for diagnosis. Radiologically suspicious lymph nodes are also an important component of the staging workup and are discussed further in the mediastinum section.

The Lung Frozen Section: Major Intraoperative Questions

The intraoperative evaluation of a lung wedge biopsy needs to be accompanied by important clinical history, including suspicion of tuberculosis or lymphoma, and the appropriate precautions taken. The specimen should be measured and inked. The staple line should be removed with minimal disruption of the underlying tissue, and the resection margin should then be inked a different color than used before. In some cases, freezing a portion of the nodule with a portion of adjacent lung parenchyma may reveal an adjacent in situ component which would indicate a primary lung lesion. It is important to note that sections of the nodule at its closest approach to the pleura should not be frozen, as pleural involvement by carcinoma is important for surgical staging of tumors smaller than 3 cm. These sections should always be submitted for permanent paraffin sections for adequate assessment of pleural involvement.

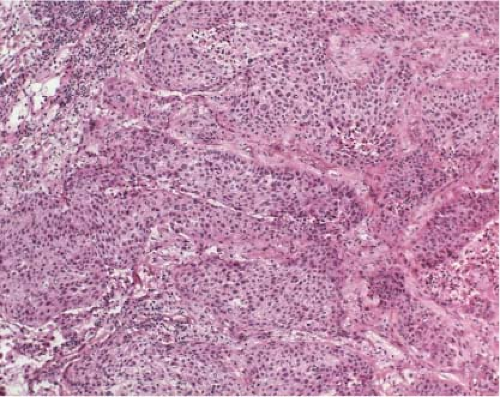

The major clinical question for surgically resectable malignant peripheral lung nodules is whether it is a small cell or a nonsmall cell carcinoma (Figs. 6.1 and 6.2, e-Fig. 6.1). Small cell lung carcinoma is not typically resected, except for the small minority that present in stage I disease, while

nonsmall cell carcinoma is surgically resected when possible. The distinction between small cell carcinoma and nonsmall cell carcinoma is therefore very important in determining whether or not to continue to a definitive lobectomy and lymph node dissection. If the distinction cannot be made on frozen section, documentation that diagnostic tissue has been obtained is helpful, and the actual diagnosis can be deferred, with further surgical management as necessary.

nonsmall cell carcinoma is surgically resected when possible. The distinction between small cell carcinoma and nonsmall cell carcinoma is therefore very important in determining whether or not to continue to a definitive lobectomy and lymph node dissection. If the distinction cannot be made on frozen section, documentation that diagnostic tissue has been obtained is helpful, and the actual diagnosis can be deferred, with further surgical management as necessary.

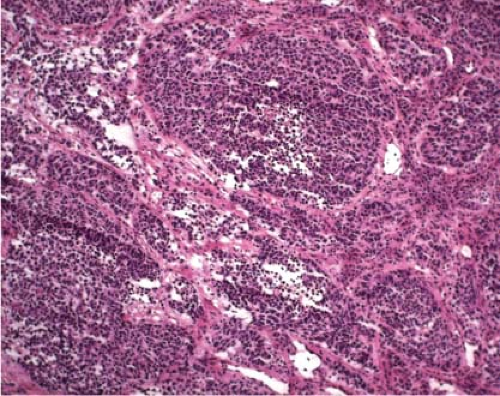

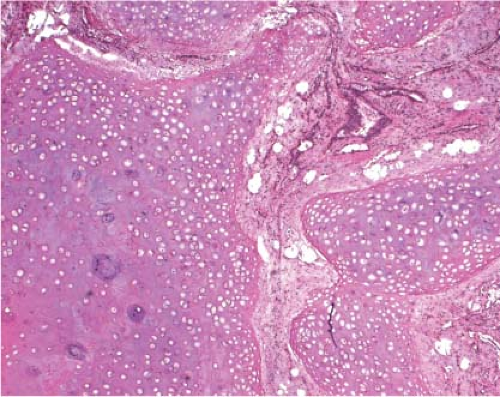

Figure 6.1 Small cell carcinoma. The tumor is composed of nests of small cells within which some pseudorosettes can be identified. |

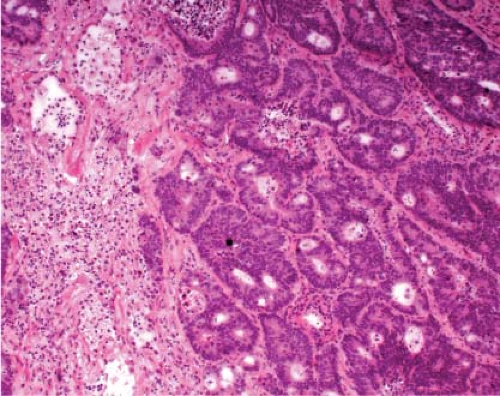

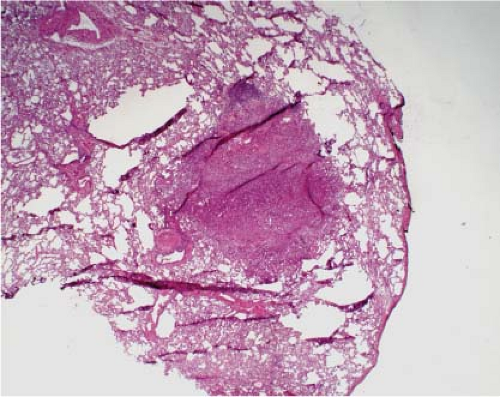

Once a malignant diagnosis is rendered on frozen section, another clinical question may be whether the lesion represents primary or metastatic disease. A round, well-circumscribed nodule lacking a central scar favors a metastasis (Fig. 6.3). Metastatic adenocarcinoma may have more complex architecture (Figs. 6.4 and 6.5), dirty necrosis (e-Fig 6.2), or bland cytology, and metastatic squamous cell carcinoma may be more differentiated with keratinization and minimal atypia compared to primary tumors (1). This may be a difficult distinction, especially by frozen section, even with previous documentation of a nonlung primary carcinoma. The expertise of the pathologist, deferral to paraffin sections, and immunohistologic workup are all factors to be considered. In equivocal cases, it is best to document that a nonsmall cell carcinoma is present, and that the primary site cannot be determined.

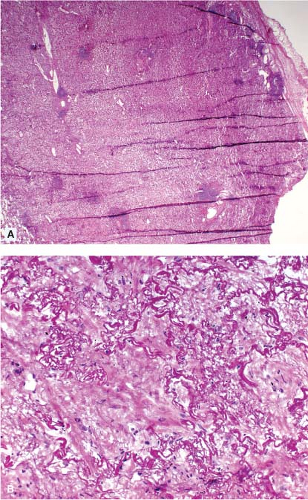

Subpleural scars (Fig. 6.6), which are linear and parallel to the pleural surface are a common finding in adults, and may be either subclinical incidental findings or identified on CT scan. The presence of a subpleural scar on gross inspection should not distract from the search for a distinct peripheral nodule, which is more likely to be the lesion in question.

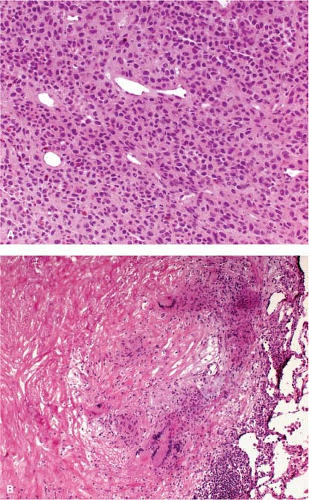

Reviewing the CT scan may be helpful in these cases. Upon thorough gross inspection of any lung wedge biopsy, incidental nodules less than 5 mm should not be frozen. These small nodules are not usually clinically worrisome and most often represent benign lesions or atypical adenomatous hyperplasia, which is best evaluated on nonfrozen sections. For cases in which it is necessary to freeze a small pulmonary nodule, it may be useful to inflate the lung with a 2:3 dilution of embedding medium in saline (2). Regardless, at least a portion of each distinct nodule greater than 5 mm should be frozen in any lung wedge biopsy sent for intraoperative consultation, as there may be more than one process present, such as a malignant tumor and organizing pneumonia (Fig. 6.7).

Reviewing the CT scan may be helpful in these cases. Upon thorough gross inspection of any lung wedge biopsy, incidental nodules less than 5 mm should not be frozen. These small nodules are not usually clinically worrisome and most often represent benign lesions or atypical adenomatous hyperplasia, which is best evaluated on nonfrozen sections. For cases in which it is necessary to freeze a small pulmonary nodule, it may be useful to inflate the lung with a 2:3 dilution of embedding medium in saline (2). Regardless, at least a portion of each distinct nodule greater than 5 mm should be frozen in any lung wedge biopsy sent for intraoperative consultation, as there may be more than one process present, such as a malignant tumor and organizing pneumonia (Fig. 6.7).

Figure 6.3 Metastatic carcinoma. Subpleural location and rounded well-defined nodule without central scar favors metastasis. |

Another common clinical question pertains to involvement of bronchial resection margins for lobectomy specimens. Surgical resection margins should be inked, and careful gross examination can reveal margin involvement. Areas of questionable involvement of a margin should be frozen to permit a thorough intraoperative assessment (e-Fig. 6.3). A study at the University of North Carolina (3) found that 5.4% of bronchial margins were positive for either in situ or invasive carcinoma, and that lymphoma, adenoid cystic/mucoepidermoid carcinoma (e-Fig. 6.4), and small cell carcinoma had a higher frequency of positive margins than nonsmall cell tumors. The presence of preinvasive bronchial squamous lesions (dysplasia or in situ carcinoma) in frozen margins may not have clinical significance (4), but should always be reported.

Figure 6.6 Subpleural scar. Low power (A) shows a mass lesion which on high power (B) has only fibrosis and no evidence of malignancy. |

Figure 6.7 Two distinct nodules were present in this wedge biopsy: Metastatic malignant melanoma (A) and partially hyalinized granuloma (B). |

Figure 6.8 Bronchial hamartoma. Small endobronchial cartilaginous lesion with bronchial epithelium and fat. |

At the University of Chicago, between 2005 and 2011, there were 317 cases of lung wedge biopsies with an intraoperative frozen section. Of these, 123 (39%) were benign and 194 (61%) were malignant. Benign lesions included granulomas, organizing pneumonia, intrapulmonary lymph nodes, and pulmonary hamartomas (Fig. 6.8), among others. Of the malignant lesions, 154 (79%) were nonsmall cell lung carcinoma, and the remaining were mostly metastases or lymphoma, with only a few cases of small cell carcinoma, carcinoid tumor, and melanoma. In 22 (11%) of the malignant cases, the specific diagnosis was deferred for permanent sections. Final diagnoses in these cases included lymphoma, large cell carcinoma, and sarcoma, among others. There were a total of 10 cases in which the final diagnosis differed from the frozen section diagnosis, the most common reason being incorrect specific diagnosis (Table 6.1).

The Lung Frozen Section and its Interpretation

There are several important factors to consider when evaluating a frozen section of a lung nodule. It is easier to interpret sections cut at a thickness of 5 μm. In thinner cuts, the architectural features are less apparent, making the diagnosis of carcinoma more difficult. Standard hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining is adequate for most cases, and care should be taken to ensure adequate hematoxylin staining to best visualize nuclear features.

Fortunately, the majority of malignant lung nodules can be readily diagnosed as small cell or nonsmall cell carcinoma on a well-cut and

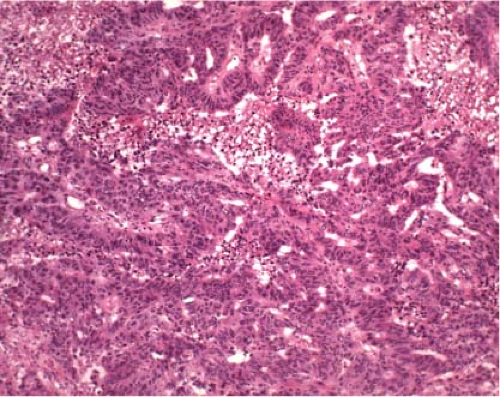

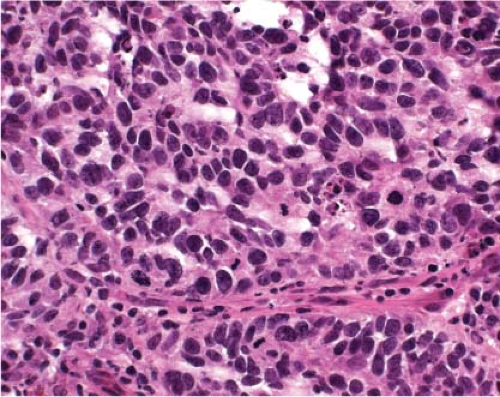

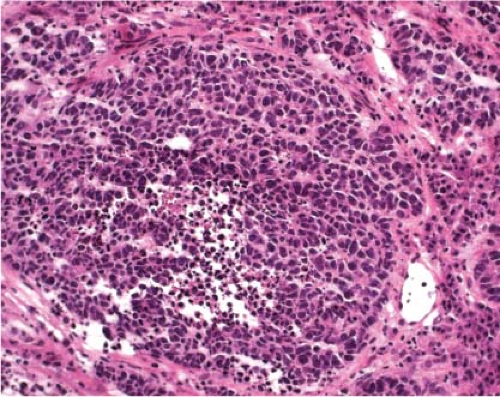

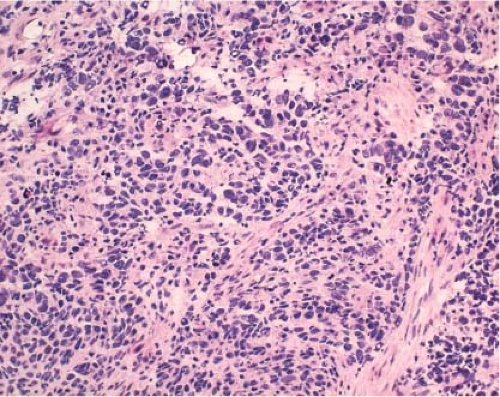

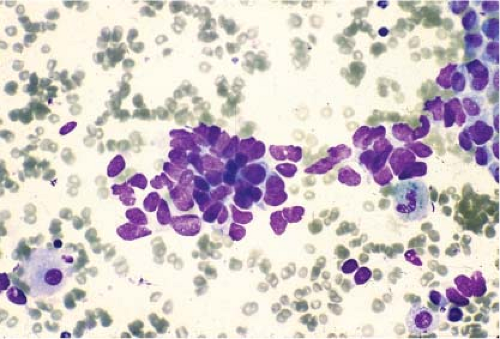

stained frozen section. Features that favor small cell over nonsmall cell include lack of prominent nucleoli, presence of salt and pepper chromatin, high mitotic activity, necrosis, and cellular crowding (Figs. 6.9 and 6.10). A potential pitfall is that resected small cell carcinoma on frozen section may exhibit a moderate amount of cytoplasm and frequently lacks the crush artifact commonly seen on nonfrozen tissue (Fig. 6.11). Imprints may be helpful in distinguishing small cell from nonsmall cell carcinoma (Figs. 6.12 and 6.13).

stained frozen section. Features that favor small cell over nonsmall cell include lack of prominent nucleoli, presence of salt and pepper chromatin, high mitotic activity, necrosis, and cellular crowding (Figs. 6.9 and 6.10). A potential pitfall is that resected small cell carcinoma on frozen section may exhibit a moderate amount of cytoplasm and frequently lacks the crush artifact commonly seen on nonfrozen tissue (Fig. 6.11). Imprints may be helpful in distinguishing small cell from nonsmall cell carcinoma (Figs. 6.12 and 6.13).

Table 6.1 Reasons for Incorrect Diagnosis (10) on Frozen Section of Lung Wedge Biopsies (317) at the University of Chicago Hospitals Between 2005 and 2011 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lung carcinoma is frequently surrounded by an inflammatory reaction or an obstructive/organizing pneumonia (Fig. 6.14), or the lesion may be partially necrotic (Fig. 6.15), which may lead to consideration of necrotizing granuloma (Fig. 6.16). Therefore, if initial sections of a suspected lung carcinoma do not reveal definitive carcinoma, deeper sections of the frozen tissue or sampling another area, ideally through the center of the lesion, should be obtained before finalizing an intraoperative diagnosis. Deeper sections of the frozen tissue should also be cut if there are only a few atypical cells present on the initial sections

(Fig. 6.17), and if a nodule is suspected clinically, but not seen on initial sections (Fig. 6.18).

(Fig. 6.17), and if a nodule is suspected clinically, but not seen on initial sections (Fig. 6.18).

Figure 6.9 Small cell carcinoma frozen section showing nuclear crowding and necrosis. These features favor small cell over nonsmall cell carcinoma. |

Figure 6.11 As opposed to bronchoscopic biopsies, frozen sections of small cell carcinoma often are well-preserved, have moderate cytoplasm, and lack crush artifact. |

Figure 6.12 Small cell carcinoma touch preparation. Note lack of nucleoli, nuclear molding, and scant cytoplasm. (Courtesy of Dr. Jerome B. Taxy, University of Chicago.) |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree