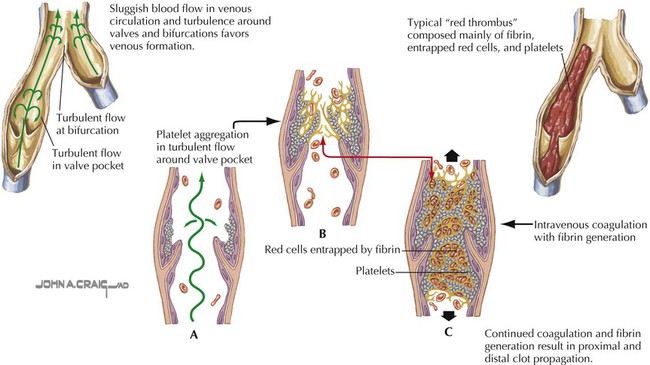

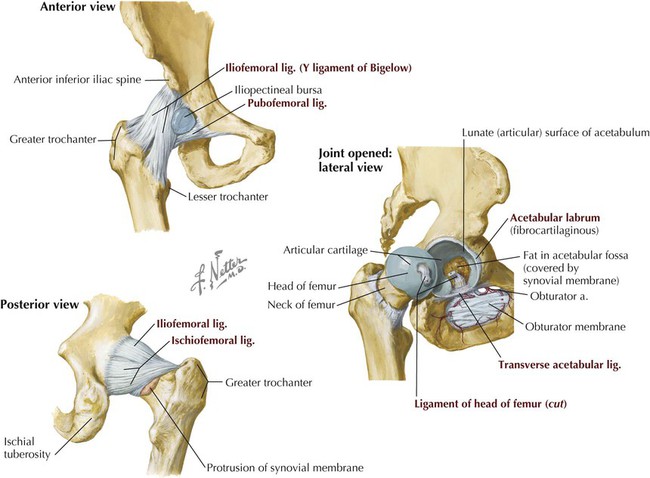

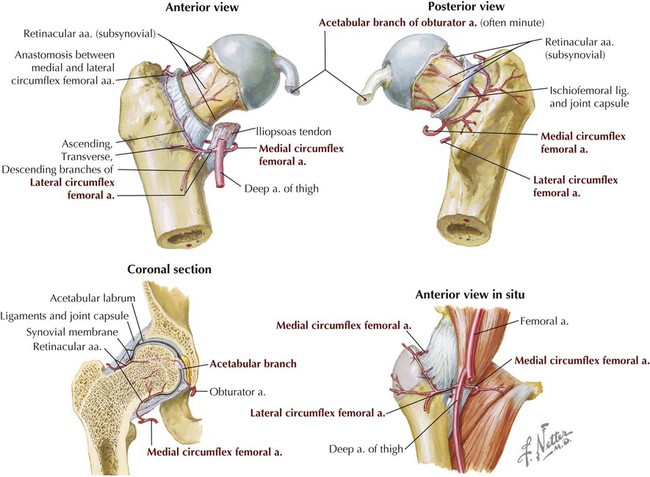

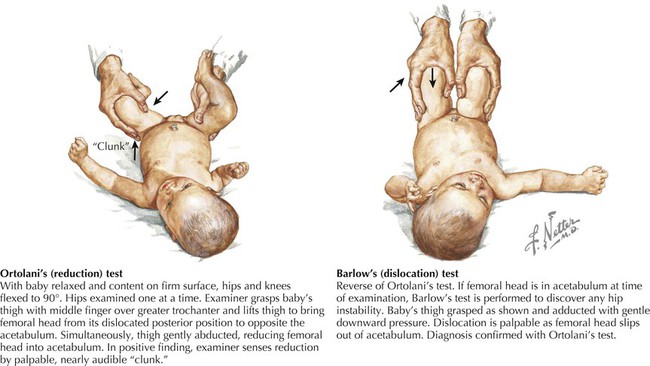

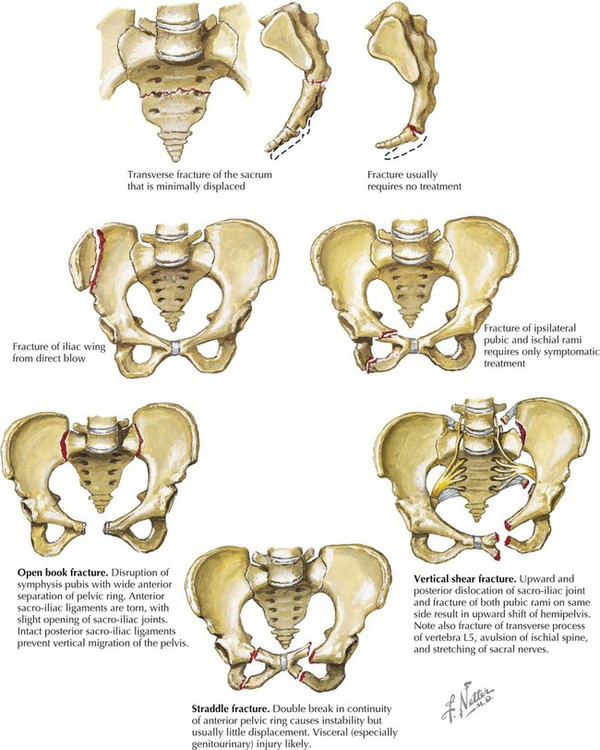

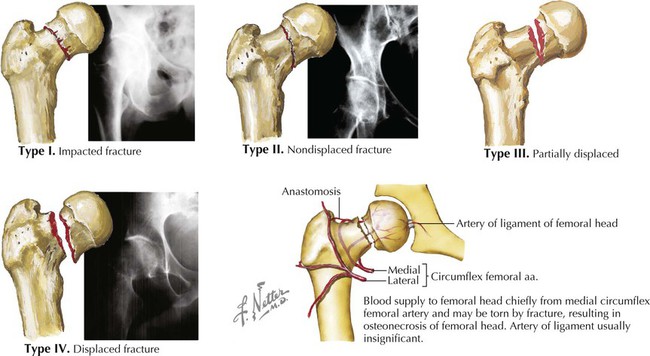

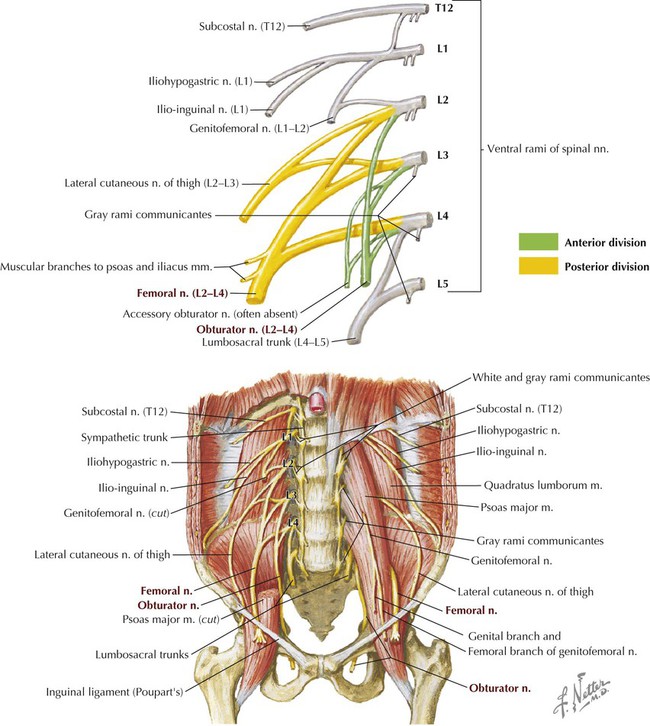

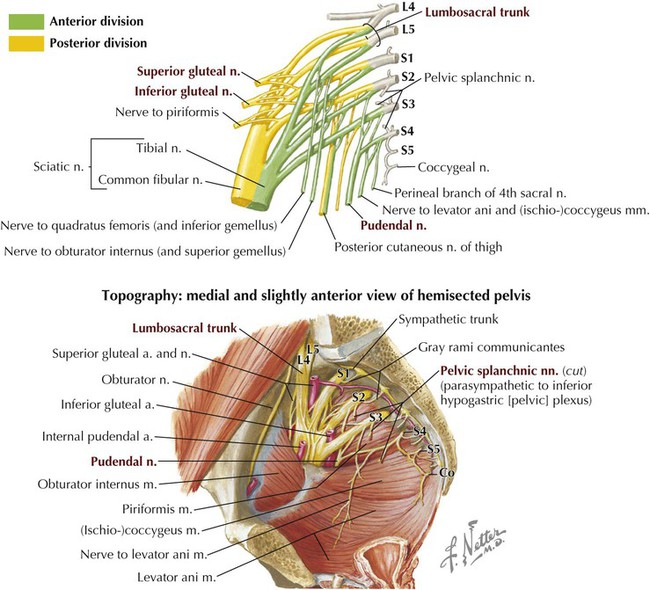

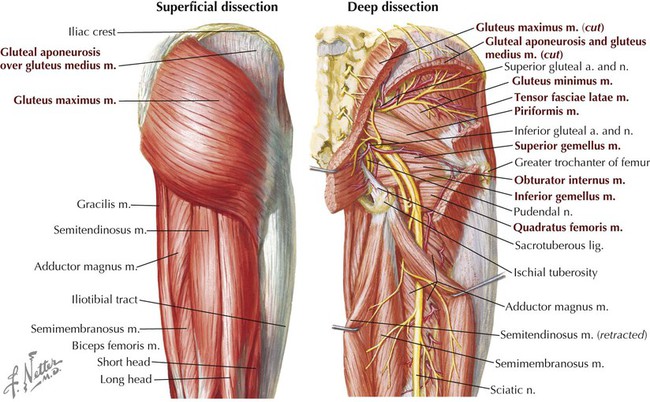

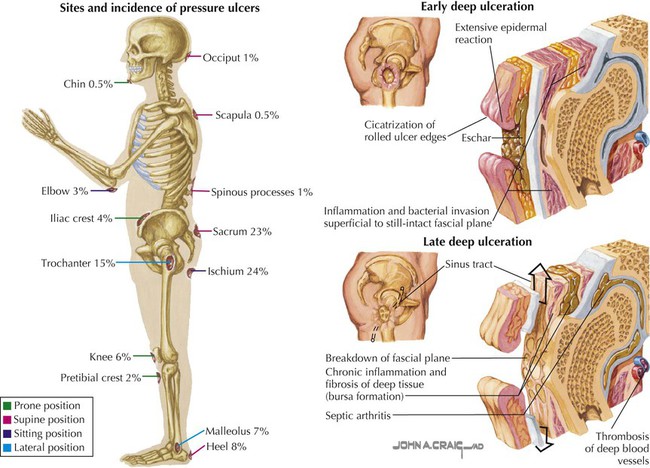

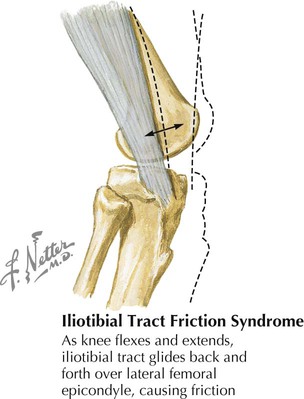

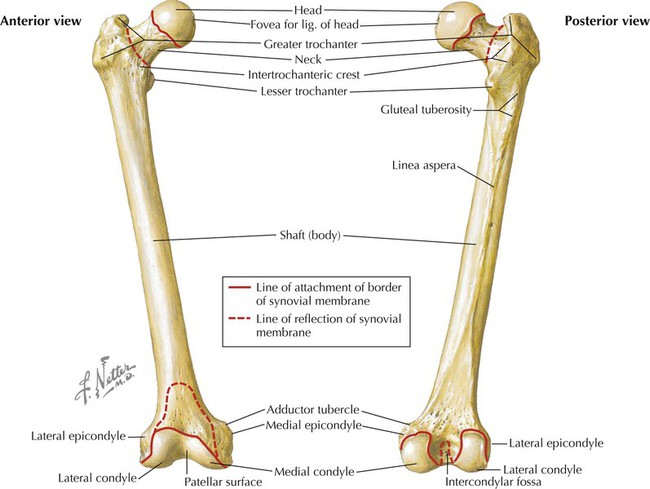

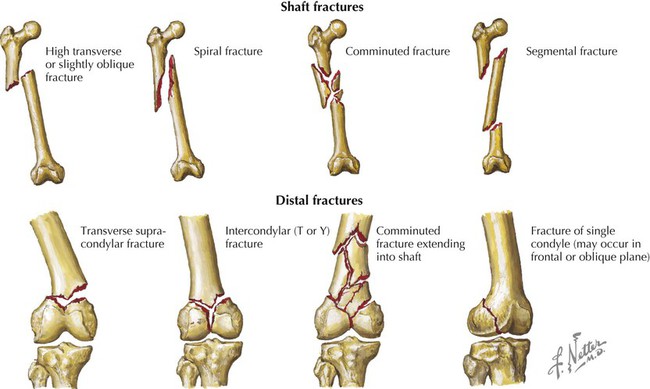

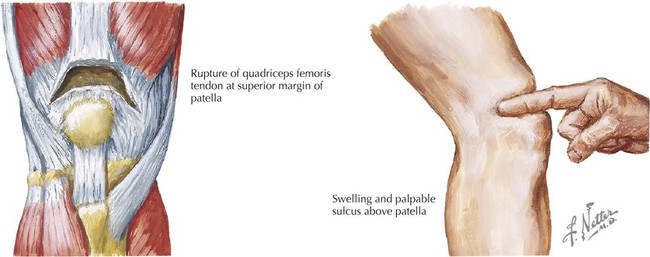

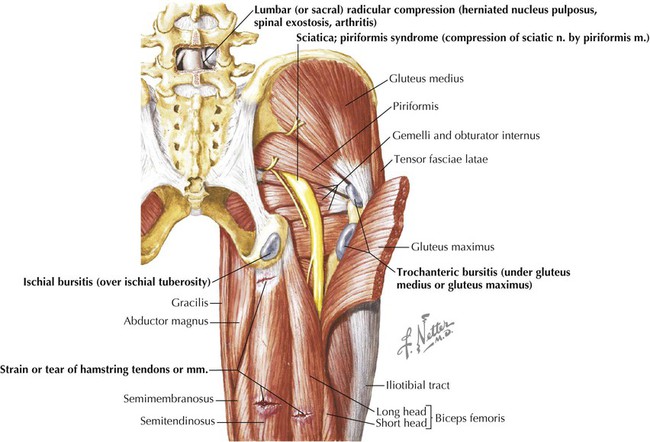

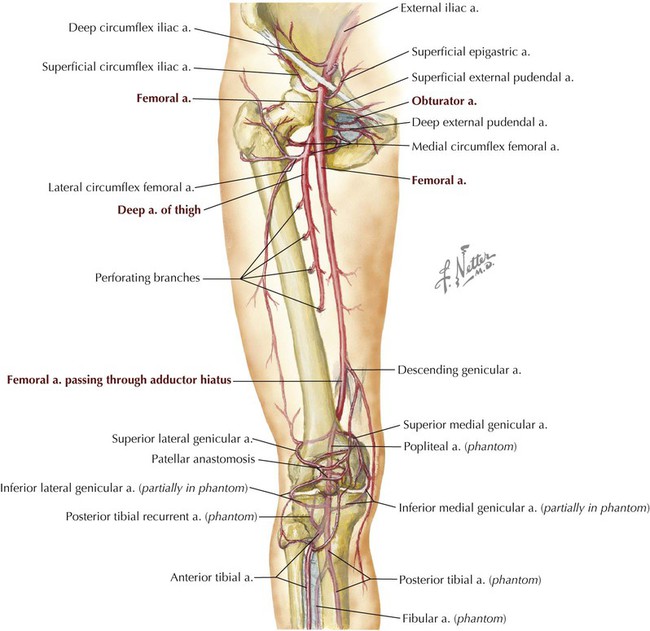

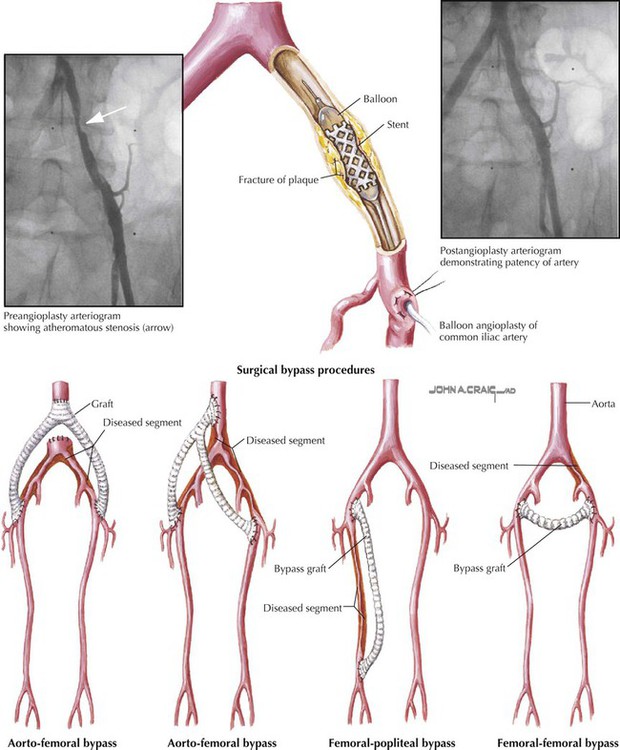

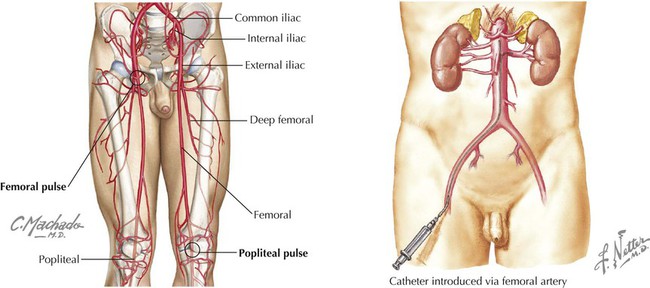

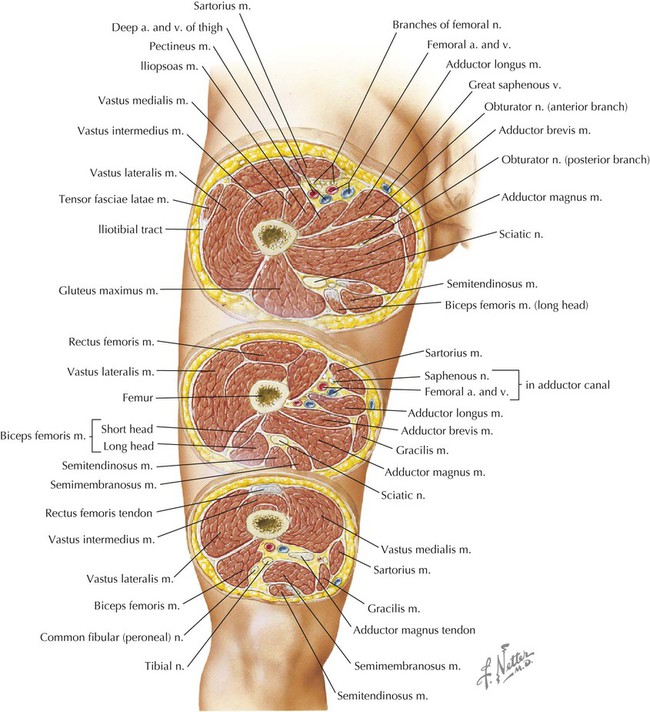

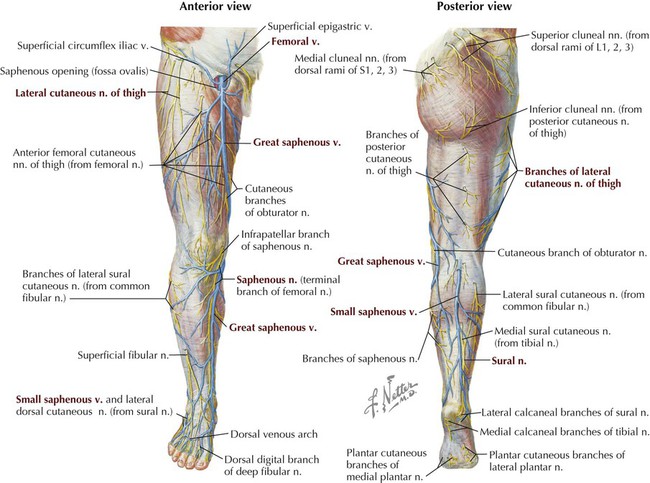

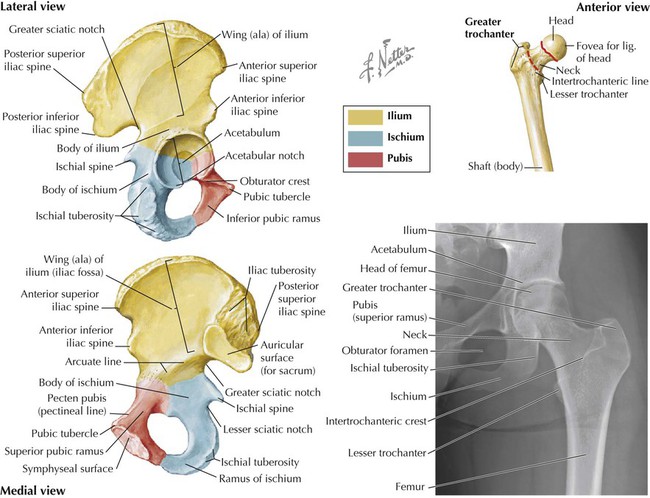

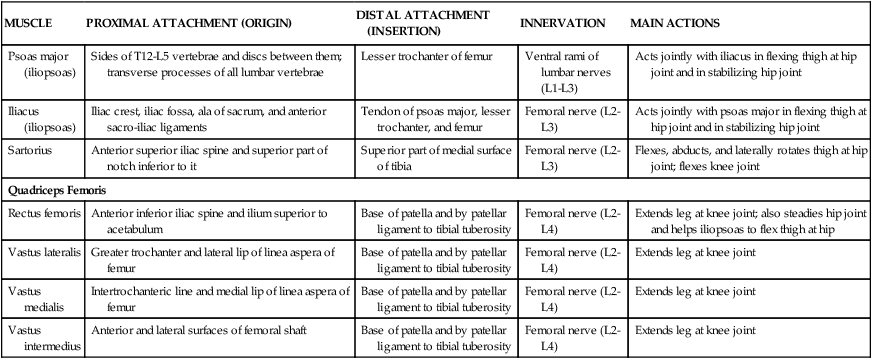

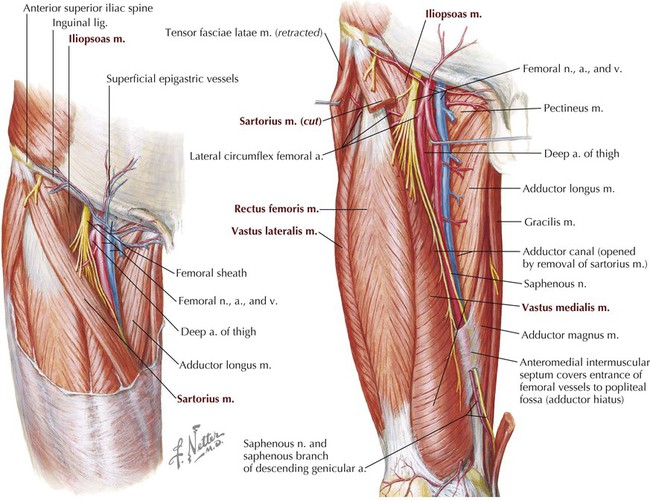

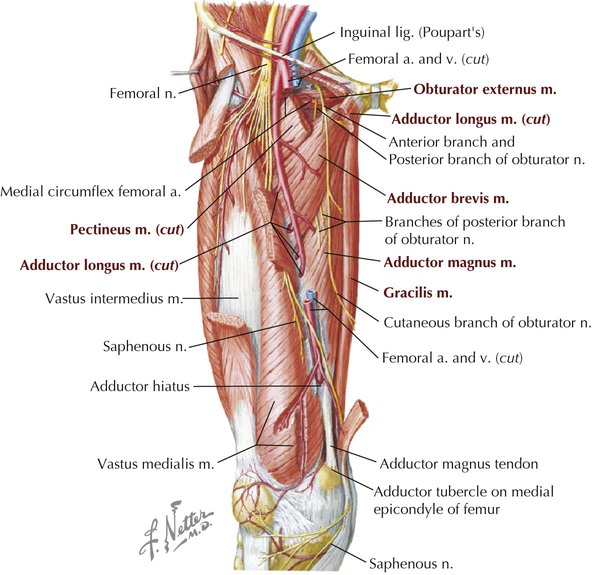

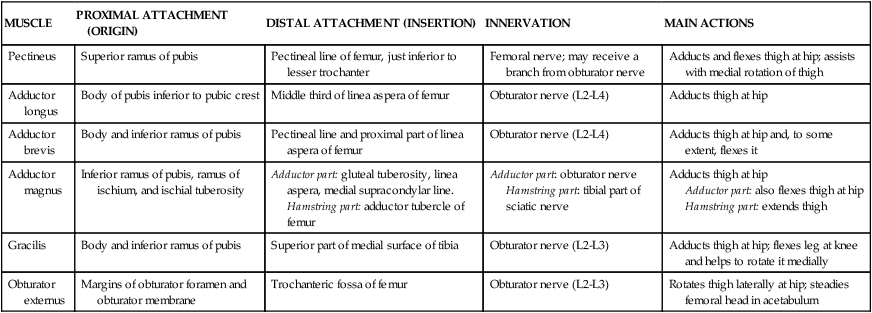

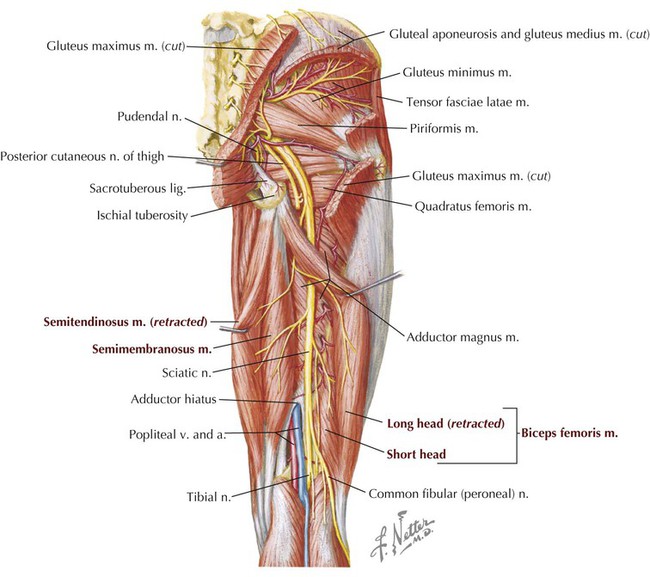

As with the upper limb in Chapter 7, this chapter approaches our study of the lower limb by organizing its anatomical structures into functional compartments. The thigh and leg each are organized into three functional compartments, with their respective muscles and neurovascular bundles. The lower limb subserves the following important functions and features: • Supports the weight of the body, and transfers that support to the axial skeleton across the hip and sacro-iliac joints. • The hip and knee joints lock into position when standing still in anatomical position, adding stability and balance to the transfer of weight and conserving the muscles’ energy; this allows one to stand erect for prolonged periods. • Functions in locomotion through the process of walking (our gait). • Anchored to the axial skeleton by the pelvic girdle, which allows for less mobility but significantly more stability than the pectoral girdle of the upper limb. Be sure to review the movements of the lower limb as described in Chapter 1 (see Fig. 1-3). Note the terms dorsiflexion (extension) and plantarflexion (flexion), and inversion (supination) and eversion (pronation), which are unique to the movements of the ankle. The components of the lower limb include the gluteal region, thigh, leg, and foot. The key surface landmarks include the following (Fig. 6-1): • Inguinal ligament: the folded, inferior edge of the external abdominal oblique aponeurosis that separates the abdominal region from the thigh (Poupart’s ligament). • Greater trochanter: the point of the hip and attachment site for several gluteal muscles. • Quadriceps femoris: the muscle mass of the anterior thigh, composed of four muscles—rectus femoris and three vastus muscles—that extend the leg at the knee. • Patella: the kneecap; largest sesamoid bone in the body. • Popliteal fossa: the region posterior to the knee. • Gastrocnemius muscles: the muscle mass that forms the calf. • Calcaneal (Achilles) tendon: the prominent tendon of several calf muscles. • Small saphenous vein: drains blood from the lateral dorsal venous arch and posterior leg (calf) into the popliteal vein posterior to the knee. • Great saphenous vein: drains blood from the medial dorsal venous arch, leg, and thigh into the femoral vein just inferior to the inguinal ligament. Corresponding cutaneous nerves are terminal sensory branches of major lower limb nerves that arise from lumbar (L1-L4) and sacral (L4-S4) plexuses (Fig. 6-2). Note that the gluteal region has superior, middle, and inferior cluneal nerves, and the thigh has posterior, lateral, anterior, and medial cutaneous nerves. The leg has lateral sural, superficial fibular, saphenous, and sural cutaneous nerves (named from the lateral leg to the posterior leg). The sural nerve on the posterior leg parallels the small saphenous vein, and the saphenous nerve (terminal portion of the femoral nerve) parallels the great saphenous vein from the medial ankle to the level of the knee. The pelvic girdle is the attachment point of the lower limb to the body’s trunk and axial skeleton. The pectoral girdle is its counterpart for the attachment of the upper limb. The sacro-iliac ligaments (posterior, anterior, and interosseous) are among the strongest ligaments in the body and support its entire weight, almost pulling the sacrum into the pelvis. Note that the pelvis (sacrum and coxal bones) in anatomical position is tilted forward such that the pubic symphysis and the anterior superior iliac spines lie in the same vertical plane, placing great stress on the sacro-iliac joints and ligaments (see Figs. 5-3 and 6-3). In fact, the body’s center of gravity when standing upright lies just anterior to the S2 vertebra of the fused sacrum. The bones of the pelvis include the following (Fig. 6-3 and Table 6-1): TABLE 6-1 Features of the Pelvis and Proximal Femur • Right and left pelvic bones (coxal or hip bones): the fusion of three separate bones called the ilium, ischium, and pubis, which join each other in the acetabulum (cup-shaped feature for articulation of the head of the femur). • Sacrum: the fusion of the five sacral vertebrae; the two pelvic bones articulate with the sacrum posteriorly. • Coccyx: the terminal end of the vertebral column, and a remnant of our embryonic tail. Additionally, the proximal femur (thigh bone) articulates with the pelvis at the acetabulum (see Fig. 6-3 and Table 6-1). The hip joint is a classic ball-and-socket synovial joint that affords great stability, provided by both its bony anatomy and its strong ligaments (Fig. 6-4 and Table 6-2). As with most large joints, there is a rich vascular anastomosis around the hip joint, contributing a blood supply not only to the hip but also to the associated muscles (Fig. 6-5 and Table 6-3). TABLE 6-2 Ligaments of the Hip Joint (Multiaxial Synovial Ball and Socket) TABLE 6-3 The other features of the pelvic girdle and its stabilizing lumbosacral and sacro-iliac joints are illustrated and summarized in Chapter 5. Several nerve plexuses exist within the pelvis and send branches to somatic structures (skin and skeletal muscle) of the pelvis and lower limb. The lumbar plexus is composed of the ventral rami of spinal nerves L1-L4, which give rise to two large nerves, the femoral and obturator nerves, and several smaller branches (Fig. 6-6). The femoral nerve (L2-L4) innervates muscles of the anterior thigh, whereas the obturator nerve (L2-L4) innervates muscles of the medial thigh. The sacral plexus is composed of the ventral rami of spinal nerves L4-S4. Its major branches are summarized in Figure 6-7 and Table 6-4. The small coccygeal plexus has contributions from S4-Co1 and gives rise to small anococcygeal branches that innervate the coccygeus muscle and skin of the anal triangle (see Chapter 5). Often the lumbar and sacral plexuses are simply referred to as the lumbosacral plexus. TABLE 6-4 Major Branches of the Sacral Plexus Structures passing out of or into the lower limb from the abdominopelvic cavity may do so through one of the following four passageways (see Figs. 5-3 and 6-10): • Anteriorly between the inguinal ligament and bony pelvis into the anterior thigh • Anteroinferiorly through the obturator canal into the medial thigh • Posterolaterally through the greater sciatic foramen into the gluteal region • Posterolaterally through the lesser sciatic foramen from the gluteal region into the perineum (via the pudendal [Alcock’s] canal) The muscles of the gluteal (buttock) region are arranged into superficial and deep groups, as follows (Fig. 6-8 and Table 6-5): TABLE 6-5 • Superficial muscles include the three gluteal muscles and the tensor fasciae latae laterally. • Deep muscles act on the hip, primarily as lateral rotators of the thigh at the hip, and assist in stabilizing the hip joint. The gluteus maximus muscle is one of the strongest muscles in the body in absolute terms and is a powerful extensor of the thigh at the hip (Fig. 6-8). It is especially important in extending the hip when rising from a squatting or sitting position, and when climbing stairs. The gluteus maximus also stabilizes and laterally rotates the hip joint. The gluteus medius and gluteus minimus muscles are primarily abductors and medial rotators of the thigh at the hip, steadying the pelvis over the lower limb when the opposite lower limb is raised off the ground (see Fig. 6-34). The nerves innervating the gluteal muscles arise from the sacral plexus (see Figs. 6-7 and 6-8 and Tables 6-4 and 6-5) and gain access to the gluteal region largely by passing through the greater sciatic foramen. The blood supply to this region is via the superior and inferior gluteal arteries, which are branches of the internal iliac artery in the pelvis (see also Fig. 5-13 and Table 5-6) and also gain access to the gluteal region via the greater sciatic foramen. These neurovascular elements pass in the plane deep to the gluteus medius muscle (superior gluteal neurovascular bundle) or deep to the gluteus maximus muscle (inferior gluteal neurovascular structures). Also passing through the gluteal region is the largest nerve in the body, the sciatic nerve (L4-S3), which exits the greater sciatic foramen, passes through or more often inferior to the piriformis muscle, and enters the posterior thigh passing deep to the long head of the biceps femoris muscle (see Fig. 6-8). The internal pudendal artery and pudendal nerve (a somatic nerve, S2-S4) pass out of the greater sciatic foramen, wrap around the sacrospinous ligament, and reenter the lesser sciatic foramen to gain access to the pudendal (Alcock’s) canal (see Figs. 5-22 and 6-8). The pudendal nerve innervates the skeletal muscle and skin of the perineum (see Table 6-4). The internal pudendal artery is the major blood supply to the perineum and external genitalia. The femur, the longest bone in the body, is the bone of the thigh. It is slightly bowed anteriorly and runs slightly diagonally, lateral to medial, from the hip to the knee (Fig. 6-9 and Table 6-6). Proximally the femur articulates with the pelvis, and distally it articulates with the tibia and the patella (kneecap), which is the largest sesamoid bone in the body. The proximal femur is supplied with blood from the medial and lateral femoral circumflex branches of the deep femoral artery (see Fig. 6-13), an acetabular branch of the obturator artery, and by anastomotic branches of the inferior gluteal artery. The shaft and distal femur is supplied by femoral nutrient arteries and by anastomotic branches of the popliteal artery, the distal continuation of the femoral artery posterior to the knee. TABLE 6-6 Muscles of the anterior compartment exhibit the following characteristics (Figs. 6-10 and 6-11 and Table 6-7): TABLE 6-7 Anterior Compartment Thigh Muscles • Include the quadriceps muscles, which attach to the patella by the quadriceps femoris tendon and to the tibia by the patellar ligament (clinicians often refer to this ligament as the “patellar tendon”). • Are primarily extensors of the leg at the knee. • Two can secondarily flex the thigh at the hip (sartorius and rectus femoris). • Are innervated by the femoral nerve. • Are supplied by the femoral artery and its deep (femoral) artery of the thigh. Additionally, the psoas major and iliacus muscles (which form the iliopsoas) pass from the posterior abdominal wall to the anterior thigh by passing deep to the inguinal ligament to insert on the lesser trochanter of the femur. These muscles act jointly as powerful flexors of the thigh at the hip joint (Table 6-7; see also Fig. 4-32). Muscles of the medial compartment exhibit the following characteristics (see Figs. 6-10 and 6-11 and Table 6-8): TABLE 6-8 Medial Compartment Thigh Muscles • Are primarily adductors of the thigh at the hip. • Most can secondarily flex and/or rotate the thigh. • Are largely innervated by the obturator nerve. • Are supplied by the obturator artery and deep (femoral) artery of the thigh. Muscles of the posterior compartment exhibit the following characteristics (Fig. 6-12 and Table 6-9; see Fig. 6-8): TABLE 6-9 Posterior Compartment Thigh Muscles • Are largely flexors of the leg at the knee and extensors of the thigh at the hip (except the short head of the biceps femoris muscle). • Are collectively referred to as the hamstrings; can also rotate the knee and are attached proximally to the ischial tuberosity (except the short head of biceps femoris). • Are innervated by the tibial division of the sciatic nerve (except short head of biceps femoris, which is innervated by common fibular division). • Are supplied by the deep (femoral) artery of the thigh and the femoral artery. The femoral triangle is located on the anterosuperior aspect of the thigh and is bound by the following structures (see Fig. 6-10): • Inguinal ligament: forms the base of the triangle. • Sartorius muscle: forms the lateral boundary. Inferiorly, a fascial sleeve extends from the apex of the femoral triangle and is continuous with the adductor (Hunter’s) canal; the femoral vessels course through this canal and become the popliteal vessels posterior to the knee. The femoral triangle contains the femoral nerve and vessels as they pass beneath the inguinal ligament and gain access to the anterior thigh (see Fig. 6-10). Within this triangle is a fascial sleeve called the femoral sheath, a continuation of transversalis fascia and iliac fascia of the abdomen, that contains the femoral artery and vein and medially the lymphatics. Laterally the femoral nerve lies within the femoral triangle but outside this femoral sheath. The most medial portion of the femoral sheath is called the femoral canal and contains the lymphatics that drain through the femoral ring and into the external iliac lymph nodes. The femoral canal and ring are a weak point and the site for femoral hernias. The femoral ring is narrow, and consequently, femoral hernias may be difficult to reduce and may be prone to strangulation. The femoral artery supplies the tissues of the thigh and then descends into the adductor canal to gain access to the popliteal fossa (Fig. 6-13 and Table 6-10). The superomedial aspect of the thigh also is supplied by the obturator artery. These vessels form anastomoses around the hip and, in the case of the femoral-popliteal artery, around the knee as well (see Fig. 6-13). TABLE 6-10 Cross sections of the thigh show the three compartments and their respective muscles and neurovascular elements (Fig. 6-14). Lateral, medial, and posterior intermuscular septae divide the thigh into the following three sections: • Anterior compartment: contains muscles that primarily extend the leg at the knee and are innervated by the femoral nerve. • Medial compartment: contains muscles that primarily adduct the thigh at the hip and are innervated largely by the obturator nerve. • Posterior compartment: contains muscles that primarily extend the thigh at the hip and flex the leg at the knee and are innervated by the sciatic nerve (tibial portion).

Lower Limb

1 Introduction

2 Surface Anatomy

3 Hip

Bones and Joints of the Pelvic Girdle and Hip

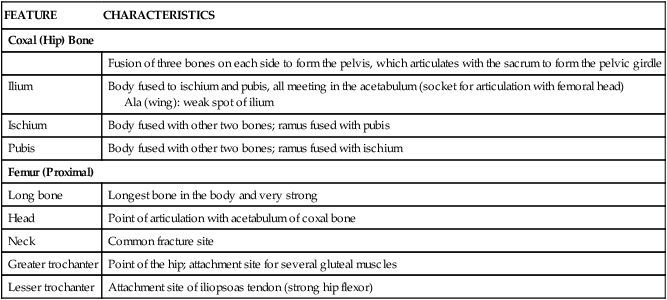

FEATURE

CHARACTERISTICS

Coxal (Hip) Bone

Fusion of three bones on each side to form the pelvis, which articulates with the sacrum to form the pelvic girdle

Ilium

Body fused to ischium and pubis, all meeting in the acetabulum (socket for articulation with femoral head)

Ala (wing): weak spot of ilium

Ischium

Body fused with other two bones; ramus fused with pubis

Pubis

Body fused with other two bones; ramus fused with ischium

Femur (Proximal)

Long bone

Longest bone in the body and very strong

Head

Point of articulation with acetabulum of coxal bone

Neck

Common fracture site

Greater trochanter

Point of the hip; attachment site for several gluteal muscles

Lesser trochanter

Attachment site of iliopsoas tendon (strong hip flexor)

LIGAMENT

ATTACHMENT

COMMENT

Capsular

Acetabular margin to femoral neck

Encloses femoral head and part of neck; acts in flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, medial and lateral rotation, and circumduction

Iliofemoral

Iliac spine and acetabulum to intertrochanteric line

Forms inverted Y (of Bigelow); limits hyperextension and lateral rotation; the stronger ligament

Ischiofemoral

Acetabulum to femoral neck posteriorly

Limits extension and medial rotation; the weaker ligament

Pubofemoral

Pubic ramus to lower femoral neck

Limits extension and abduction

Labrum

Acetabulum

Fibrocartilage, deepens socket

Transverse acetabular

Acetabular notch inferiorly

Cups acetabulum to form a socket for femoral head

Ligament of head of femur

Acetabular notch and transverse ligament to femoral head

Artery to femoral head runs in ligament

ARTERY

COURSE AND STRUCTURES SUPPLIED

Medial circumflex

Usually arises from deep artery of thigh; branches supply femoral head and neck; passes posterior to iliopsoas muscle tendon

Lateral circumflex

Usually arises from deep artery of the thigh

Acetabular branch

Arises from obturator artery; runs in ligament of head of femur; supplies femoral head

Gluteal branches (superior and inferior)

Form anastomoses with medial and lateral femoral circumflex branches

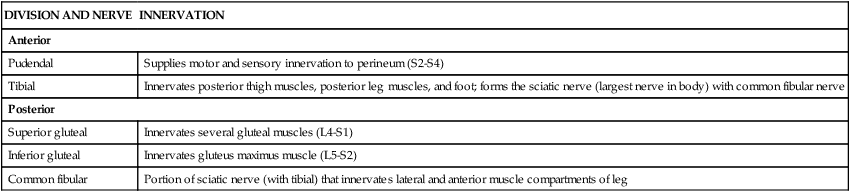

Nerve Plexuses

DIVISION AND NERVE

INNERVATION

Anterior

Pudendal

Supplies motor and sensory innervation to perineum (S2-S4)

Tibial

Innervates posterior thigh muscles, posterior leg muscles, and foot; forms the sciatic nerve (largest nerve in body) with common fibular nerve

Posterior

Superior gluteal

Innervates several gluteal muscles (L4-S1)

Inferior gluteal

Innervates gluteus maximus muscle (L5-S2)

Common fibular

Portion of sciatic nerve (with tibial) that innervates lateral and anterior muscle compartments of leg

Access to the Lower Limb

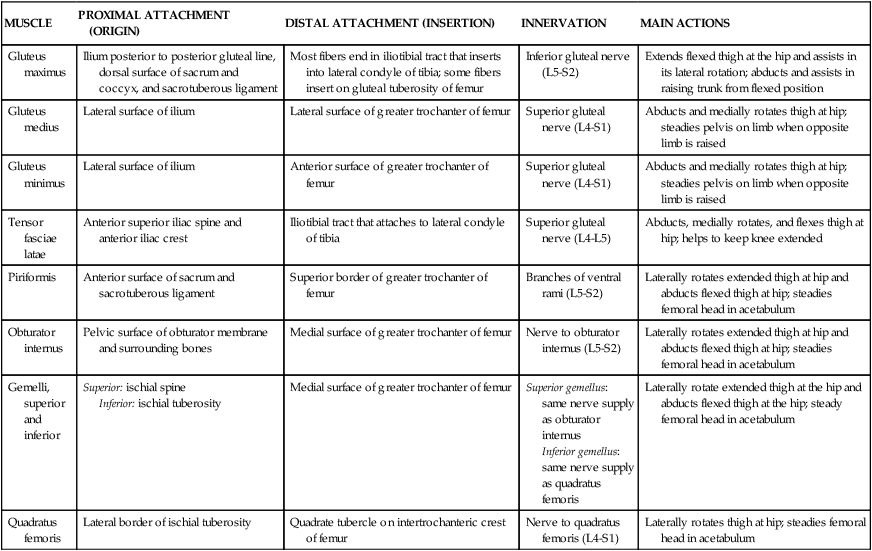

4 Gluteal Region

Muscles

MUSCLE

PROXIMAL ATTACHMENT (ORIGIN)

DISTAL ATTACHMENT (INSERTION)

INNERVATION

MAIN ACTIONS

Gluteus maximus

Ilium posterior to posterior gluteal line, dorsal surface of sacrum and coccyx, and sacrotuberous ligament

Most fibers end in iliotibial tract that inserts into lateral condyle of tibia; some fibers insert on gluteal tuberosity of femur

Inferior gluteal nerve (L5-S2)

Extends flexed thigh at the hip and assists in its lateral rotation; abducts and assists in raising trunk from flexed position

Gluteus medius

Lateral surface of ilium

Lateral surface of greater trochanter of femur

Superior gluteal nerve (L4-S1)

Abducts and medially rotates thigh at hip; steadies pelvis on limb when opposite limb is raised

Gluteus minimus

Lateral surface of ilium

Anterior surface of greater trochanter of femur

Superior gluteal nerve (L4-S1)

Abducts and medially rotates thigh at hip; steadies pelvis on limb when opposite limb is raised

Tensor fasciae latae

Anterior superior iliac spine and anterior iliac crest

Iliotibial tract that attaches to lateral condyle of tibia

Superior gluteal nerve (L4-L5)

Abducts, medially rotates, and flexes thigh at hip; helps to keep knee extended

Piriformis

Anterior surface of sacrum and sacrotuberous ligament

Superior border of greater trochanter of femur

Branches of ventral rami (L5-S2)

Laterally rotates extended thigh at hip and abducts flexed thigh at hip; steadies femoral head in acetabulum

Obturator internus

Pelvic surface of obturator membrane and surrounding bones

Medial surface of greater trochanter of femur

Nerve to obturator internus (L5-S2)

Laterally rotates extended thigh at hip and abducts flexed thigh at hip; steadies femoral head in acetabulum

Gemelli, superior and inferior

Superior: ischial spine

Inferior: ischial tuberosity

Medial surface of greater trochanter of femur

Superior gemellus: same nerve supply as obturator internus

Inferior gemellus: same nerve supply as quadratus femoris

Laterally rotate extended thigh at the hip and abducts flexed thigh at the hip; steady femoral head in acetabulum

Quadratus femoris

Lateral border of ischial tuberosity

Quadrate tubercle on intertrochanteric crest of femur

Nerve to quadratus femoris (L4-S1)

Laterally rotates thigh at hip; steadies femoral head in acetabulum

Neurovascular Structures

5 Thigh

Bones

STRUCTURE

CHARACTERISTICS

Long bone

Longest bone in the body; very strong

Head

Point of articulation with acetabulum of coxal bone

Neck

Common fracture site

Greater trochanter

Point of hip; attachment site for several gluteal muscles

Lesser trochanter

Attachment site of iliopsoas tendon (strong hip flexor)

Distal condyles

Medial and lateral (smaller) sites that articulate with tibial condyles

Patella

Sesamoid bone (largest) embedded in quadriceps femoris tendon

Anterior Compartment Thigh Muscles, Vessels, and Nerves

MUSCLE

PROXIMAL ATTACHMENT (ORIGIN)

DISTAL ATTACHMENT (INSERTION)

INNERVATION

MAIN ACTIONS

Psoas major (iliopsoas)

Sides of T12-L5 vertebrae and discs between them; transverse processes of all lumbar vertebrae

Lesser trochanter of femur

Ventral rami of lumbar nerves (L1-L3)

Acts jointly with iliacus in flexing thigh at hip joint and in stabilizing hip joint

Iliacus (iliopsoas)

Iliac crest, iliac fossa, ala of sacrum, and anterior sacro-iliac ligaments

Tendon of psoas major, lesser trochanter, and femur

Femoral nerve (L2-L3)

Acts jointly with psoas major in flexing thigh at hip joint and in stabilizing hip joint

Sartorius

Anterior superior iliac spine and superior part of notch inferior to it

Superior part of medial surface of tibia

Femoral nerve (L2-L3)

Flexes, abducts, and laterally rotates thigh at hip joint; flexes knee joint

Quadriceps Femoris

Rectus femoris

Anterior inferior iliac spine and ilium superior to acetabulum

Base of patella and by patellar ligament to tibial tuberosity

Femoral nerve (L2-L4)

Extends leg at knee joint; also steadies hip joint and helps iliopsoas to flex thigh at hip

Vastus lateralis

Greater trochanter and lateral lip of linea aspera of femur

Base of patella and by patellar ligament to tibial tuberosity

Femoral nerve (L2-L4)

Extends leg at knee joint

Vastus medialis

Intertrochanteric line and medial lip of linea aspera of femur

Base of patella and by patellar ligament to tibial tuberosity

Femoral nerve (L2-L4)

Extends leg at knee joint

Vastus intermedius

Anterior and lateral surfaces of femoral shaft

Base of patella and by patellar ligament to tibial tuberosity

Femoral nerve (L2-L4)

Extends leg at knee joint

Medial Compartment Thigh Muscles, Vessels, and Nerves

MUSCLE

PROXIMAL ATTACHMENT (ORIGIN)

DISTAL ATTACHMENT (INSERTION)

INNERVATION

MAIN ACTIONS

Pectineus

Superior ramus of pubis

Pectineal line of femur, just inferior to lesser trochanter

Femoral nerve; may receive a branch from obturator nerve

Adducts and flexes thigh at hip; assists with medial rotation of thigh

Adductor longus

Body of pubis inferior to pubic crest

Middle third of linea aspera of femur

Obturator nerve (L2-L4)

Adducts thigh at hip

Adductor brevis

Body and inferior ramus of pubis

Pectineal line and proximal part of linea aspera of femur

Obturator nerve (L2-L4)

Adducts thigh at hip and, to some extent, flexes it

Adductor magnus

Inferior ramus of pubis, ramus of ischium, and ischial tuberosity

Adductor part: gluteal tuberosity, linea aspera, medial supracondylar line.

Hamstring part: adductor tubercle of femur

Adductor part: obturator nerve

Hamstring part: tibial part of sciatic nerve

Adducts thigh at hip

Adductor part: also flexes thigh at hip

Hamstring part: extends thigh

Gracilis

Body and inferior ramus of pubis

Superior part of medial surface of tibia

Obturator nerve (L2-L3)

Adducts thigh at hip; flexes leg at knee and helps to rotate it medially

Obturator externus

Margins of obturator foramen and obturator membrane

Trochanteric fossa of femur

Obturator nerve (L2-L3)

Rotates thigh laterally at hip; steadies femoral head in acetabulum

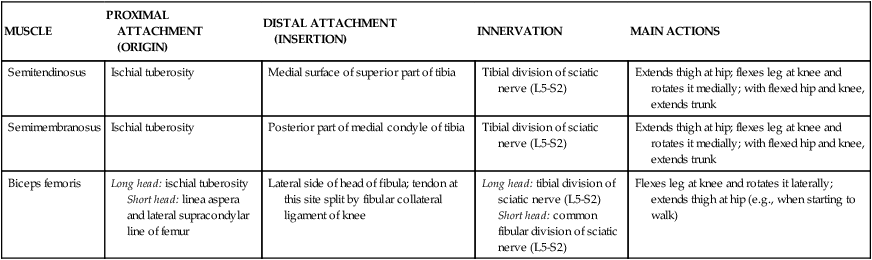

Posterior Compartment Thigh Muscles, Vessels, and Nerves

MUSCLE

PROXIMAL ATTACHMENT (ORIGIN)

DISTAL ATTACHMENT (INSERTION)

INNERVATION

MAIN ACTIONS

Semitendinosus

Ischial tuberosity

Medial surface of superior part of tibia

Tibial division of sciatic nerve (L5-S2)

Extends thigh at hip; flexes leg at knee and rotates it medially; with flexed hip and knee, extends trunk

Semimembranosus

Ischial tuberosity

Posterior part of medial condyle of tibia

Tibial division of sciatic nerve (L5-S2)

Extends thigh at hip; flexes leg at knee and rotates it medially; with flexed hip and knee, extends trunk

Biceps femoris

Long head: ischial tuberosity

Short head: linea aspera and lateral supracondylar line of femur

Lateral side of head of fibula; tendon at this site split by fibular collateral ligament of knee

Long head: tibial division of sciatic nerve (L5-S2)

Short head: common fibular division of sciatic nerve (L5-S2)

Flexes leg at knee and rotates it laterally; extends thigh at hip (e.g., when starting to walk)

Femoral Triangle

Femoral Artery

ARTERY

COURSE AND STRUCTURES SUPPLIED

Obturator

Arises from internal iliac artery (pelvis); has anterior and posterior branches; passes through obturator foramen

Femoral

Continuation of external iliac artery with numerous branches to perineum, hip, thigh, and knee

Deep artery of thigh

Arises from femoral artery; supplies hip and thigh

Thigh in Cross Section

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine