Patient Story

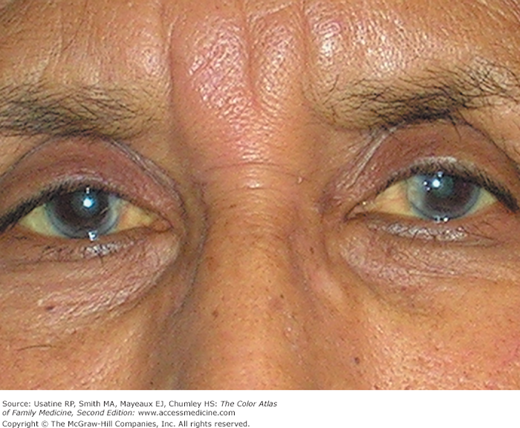

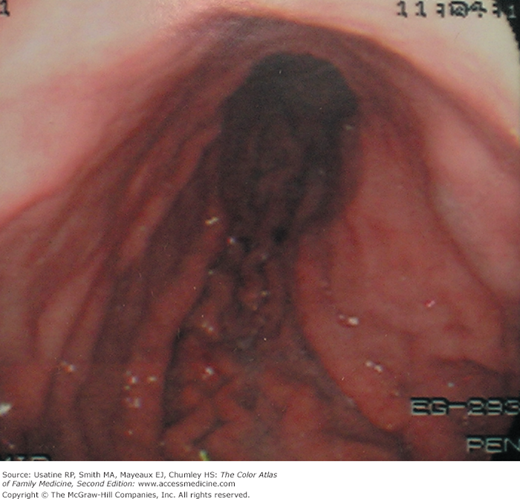

A 64-year-old woman presents with complaints of itchy skin and fatigue. She is noted on physical examination to have scleral icterus and jaundice (Figure 61-1). Laboratory testing revealed elevated liver enzymes, particularly the serum alkaline phosphatase and γ-glutamyltranspeptidase, and positive antinuclear and antimitochondrial antibodies. A liver biopsy confirmed primary biliary cirrhosis. Two months later, she vomited up some blood and on endoscopy was found to have esophageal varices from her portal hypertension (Figure 61-2).

Figure 61-2

Esophageal varices in the patient in Figure 61-1 secondary to her cirrhosis and portal hypertension. (Courtesy of Javid Ghandehari, MD.)

Introduction

Liver disease can be caused by any number of metabolic, toxic, microbial, circulatory, or neoplastic insults resulting in direct liver injury or from obstruction of bile flow or both. Liver injury falls anywhere on the spectrum from transient abnormalities in biomarkers to life-threatening multiorgan failure.

Synonyms

Epidemiology

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)—Present in 10% to 30% of adults in the general population; now the most common cause of chronic liver disease in Western countries.1 NAFLD is believed responsible for 90% of cases of elevated liver enzymes without an identifiable cause (e.g., viral hepatitis, alcohol, genetic, medications).2

- Alcohol, excessive use—Approximately 5% of the population are at risk; this includes women who drink more than two drinks per day and men who drink more than three drinks per day.3

- Drug-induced liver disease:4

- Drugs causing hepatitis include phenytoin, captopril, enalapril, isoniazid, amitriptyline, and ibuprofen.

- Drugs causing cholestasis include oral contraceptives, erythromycin, and nitrofurantoin.

- Drugs causing both of the above include azathioprine, carbamazepine, statins, nifedipine, verapamil, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

- Drugs causing hepatitis include phenytoin, captopril, enalapril, isoniazid, amitriptyline, and ibuprofen.

- Infectious disease—Viral hepatitis, infectious mononucleosis, Cytomegalovirus, and coxsackievirus are most common. Viral hepatitis infections include:

- Hepatitis A—Twenty-nine percent to 33% of patients have ever been infected with hepatitis A; there are no chronic infections.5 Incidence rates in recent years have declined with approximately 1987 cases reported and 9000 estimated in 2009.6

- Hepatitis B—Five percent to 10% of volunteer blood donors in the United States have evidence of prior infection, with 1% to 10% of those infected progressing to chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection.5 Up to 1.4 million people have chronic hepatitis B.6

- Hepatitis C—In the United States, 1.8% of the general population have had hepatitis C, with 50% to 70% developing chronic hepatitis and 80% to 90% chronic infection.5 Nearly 3.9 million have chronic hepatitis C.6

- Hepatitis D—Transmitted through contact with infectious blood and can occur as a coinfection or as a superinfection in persons with HBV infection.6

- Hepatitis E— Outbreaks are usually associated with contaminated water supply in countries with poor sanitation.6

- Hepatitis A—Twenty-nine percent to 33% of patients have ever been infected with hepatitis A; there are no chronic infections.5 Incidence rates in recent years have declined with approximately 1987 cases reported and 9000 estimated in 2009.6

- Genetic inheritance—Wilson disease (defective copper transport with copper toxicity; autosomal recessive with 1 per 40,000 affected), hemochromatosis (disorder of iron storage; autosomal recessive—among individuals of northern European heritage, 1 in 10 individuals is a heterozygous carrier and 0.3% to 0.5% have the disease), α1-antitrypsin deficiency (autosomal recessive with 1% to 2% of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease affected).

- Autoimmune liver disease—Eleven percent to 23% of patients with chronic liver disease and accounts for approximately 6% of liver transplantations in the United States.7

- Primary biliary cirrhosis (approximately 5 per 100,000 persons worldwide)—A disease of unknown etiology characterized by inflammatory destruction of the small bile ducts and gradual liver cirrhosis (Figures 61-1 and 61-2).

Etiology and Pathophysiology

- The hepatic artery (20%) and the portal vein (80%) provide the vascular supply of the liver.3 The liver is organized functionally into acini, which are divided into three zones3:

- Zone 1—The portal areas where blood enters from both sources.

- Zone 2—The hepatocytes and sinusoids where blood flows.

- Zone 3—The terminal hepatic veins.

- Zone 1—The portal areas where blood enters from both sources.

- Hepatocytes, the predominant cells in the liver, perform several vital functions, including the synthesis of essential serum proteins (e.g., albumin, coagulation factors); production of bile and its carriers (e.g., bile acids, cholesterol); regulation of nutrients (e.g., glucose, lipids, amino acids); and metabolism and conjugation of lipophilic compounds (e.g., bilirubin, various drugs) for excretion into the bile or urine.3

- There are two basic patterns of liver disease and one mixed pattern:3

- Hepatocellular—Features of this type are direct liver injury, inflammation, and necrosis. Examples are alcoholic and viral hepatitis.

- Cholestatic (obstructive)—Involves inhibition of bile flow. Examples are gallstone disease, malignancy, primary biliary cirrhosis, and some drug-induced disease.

- Both patterns—Evidence of direct damage and obstruction. Examples are cholestatic form of viral hepatitis and some drug-induced diseases.

- Hepatocellular—Features of this type are direct liver injury, inflammation, and necrosis. Examples are alcoholic and viral hepatitis.

- Cirrhosis occurs following irreversible hepatic injury with hepatocyte necrosis resulting in fibrosis and distortion of the vascular bed. This, in turn, can cause portal hypertension.

- The spectrum of NAFLD ranges from hepatic steatosis (fat deposition in liver cells) to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and cirrhosis.2 In NAFLD, steatosis occurs when free fatty acids, released in the setting of insulin resistance, are taken up by the liver; the same process can occur in alcoholism. The presence of these fatty acids leads to inflammation from other insults to the liver including oxidative stress, upregulation of inflammatory mediators, and dysregulated apoptosis, producing NASH, fibrosis, and sometimes cirrhosis (occurs in approximately 20% of patients with NASH).2

Risk Factors

- Risk factors for liver disease include:3

- Alcohol and intravenous drug use.

- Drugs (e.g., oral contraceptives).

- Personal and sexual habits.

- Travel to underdeveloped countries.

- Exposure to contaminant in food (e.g., shellfish) or individuals with liver disease (includes needle stick injuries).

- Family history.

- Blood transfusion prior to 1992.

- Alcohol and intravenous drug use.

- Obesity and the metabolic syndrome are risk factors for NAFLD and the more advanced form NASH.

Diagnosis

The goals of diagnosis are to determine the etiology and severity of the liver disease, and, where appropriate, the stage of the disease, including whether it is acute or chronic, early or late in the course of the disease, and whether there is cirrhosis present and to what degree.

- Patients with NAFLD are usually asymptomatic.

- Constitutional symptoms in patients with liver disease include fatigue (most common; especially following activity), weakness, anorexia, and nausea.

- Skin alterations:3

- Jaundice (hallmark of obstructive pattern)—Best seen in the sclera or below the tongue; the latter is particularly useful in dark-skinned individuals. Not detected until serum bilirubin levels reach 2.5 mg/dL (43 μmol/L). Early, jaundice may manifest as dark (tea colored) urine and later with light-colored stools. Jaundice without dark urine is usually from indirect hyperbilirubinemia, as seen in patients with hemolytic anemia or Gilbert syndrome.

- Palmar erythema—Can be seen in both acute and chronic disease but also seen in normal individuals and during pregnancy (Figure 61-3).

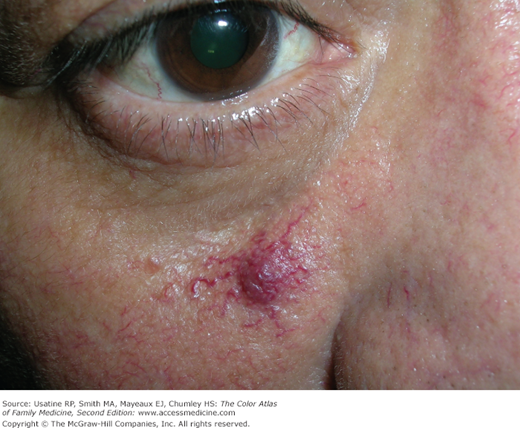

- Spider angiomas (superficial, tortuous arterioles that flow outward from the center)—Also seen in both acute and chronic disease, in normal individuals, and during pregnancy (Figure 61-4).

- Excoriations—Pruritus is prominent in acute obstructive disease and in chronic cholestatic diseases such as primary biliary cirrhosis.

- Palpable purpura—Seen with hepatitis C and chronic HBV.

- Jaundice (hallmark of obstructive pattern)—Best seen in the sclera or below the tongue; the latter is particularly useful in dark-skinned individuals. Not detected until serum bilirubin levels reach 2.5 mg/dL (43 μmol/L). Early, jaundice may manifest as dark (tea colored) urine and later with light-colored stools. Jaundice without dark urine is usually from indirect hyperbilirubinemia, as seen in patients with hemolytic anemia or Gilbert syndrome.

- Abdominal distention/bloating—Secondary to ascites (accumulation of excess fluid within the peritoneal cavity) (Figure 61-5).

- Ascites may be detected on examination by shifting dullness on percussion (ascitic fluid will flow to the most dependent portions of the abdomen and the air-filled intestines will float on top of this fluid. The fluid-air interface is detected with the patient supine and then turned onto the side where the “line” shifts upward) (Figures 61-6 and 61-7).

- Pain in the right upper quadrant (caused by stretching or irritation of the Glisson capsule surrounding the liver) with tenderness on examination in the liver area. Pain and fever in a patient with ascites should suggest the diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP).

- Hepatomegaly and splenomegaly (congestive splenomegaly from portal hypertension)—Seen in patients with cirrhosis, venoocclusive disease, malignancy, and alcoholic hepatitis.3

- Features of hyperestrogenemia in men including gynecomastia (Figure 61-8) and testicular atrophy.

- Physical signs of specific liver disease include:

- Kayser-Fleischer rings—Brown copper pigment deposits around the periphery of the cornea seen in Wilson disease (Figure 61-9).

- Excessive skin pigmentation (slate gray hue/bronzing), diabetes mellitus, polyarticular arthropathy, congestive heart failure, and hypogonadism (hemochromatosis).

- Cachexia, wasting, and firm hepatomegaly (primary hepatocellular carcinoma or metastatic liver disease).

- Kayser-Fleischer rings—Brown copper pigment deposits around the periphery of the cornea seen in Wilson disease (Figure 61-9).

- Features of patients with advanced disease include muscle wasting, ascites, edema, dilated abdominal veins (e.g., caput medusa— collateral veins seen radiating from the umbilicus), bruising, hepatic fetor (i.e., sweet, ammonia odor), asterixis (i.e., flapping of the hands when extended), and mental confusion, stupor, or coma.3

- Hepatic failure, defined as the occurrence of signs and symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy, may begin with sleep disturbance, personality changes, irritability, and mental slowness.3 Mental confusion, disorientation, or coma may occur later along with physical signs as above.

Figure 61-6

Patient with ascites and jaundice; lines drawn demonstrate the position of the fluid dullness to percussion (solid stripes), intestines (tubular structure), and the fluid intestine interface (dotted line). (Courtesy of Charlie Goldberg, MD, copyrighted by the University of California, San Diego.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree