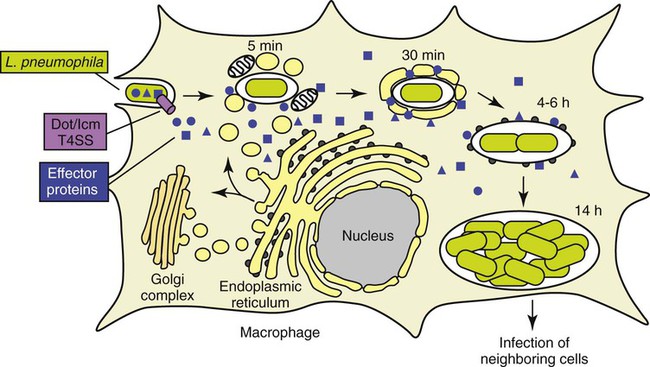

1. Identify the causative agent of Legionnaires’ disease. 2. List sources for Legionella in the environment, including those that are both man-made and naturally occurring. 3. Describe how Legionella infections are acquired. 4. Describe how Legionella avoids destruction by the host, including where the organisms survive and replicate. 5. Compare and contrast the three primary clinical manifestations of Legionella, including signs and symptoms. 6. List the specimens acceptable for Legionella testing, including storage and transportation of specimens. 7. Describe the different types of testing for Legionella, including sensitivity and specificity. 8. Explain the chemical principle for buffered charcoal-yeast extract (BCYE) with and without inhibitory agents and the proper use for each. 9. Describe the morphology of the Legionella when grown under optimal growth conditions, including oxygenation, temperature, and length of incubation. All Legionella spp. are mesophilic (20° to 45° C), obligately aerobic, faintly staining, thin, gram-negative fastidious bacilli that require a medium supplemented with iron and L-cysteine, and buffered to pH 6.9 for optimum growth. The organisms utilize protein for energy generation rather than carbohydrates. The overwhelming majority of Legionella spp. are motile. As of this writing, more than 52 species belong to this genus. Nevertheless, the organism Legionella pneumophila predominates as a human pathogen within the genus and consists of 16 serotypes. In approximately decreasing order of clinical importance are L. pneumophila serotype 1 (about 70% to 90% of the cases of Legionnaires’ disease), L. pneumophila serotype 6, L. micdadei, L. dumoffii, L. anisa, and L. feeleii. Of note, many species of Legionella have only been isolated from the environment or recorded as individual cases. To date, 20 species of Legionella are documented as human pathogens in addition to L. pneumophila. Box 35-1 is an abbreviated list of some of the species of Legionella. In eukaryotic cells, most proteins secreted or transported inside vesicles to other cellular compartments are synthesized at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Figure 35-1). Many bacterial pathogens use secretion systems as a part of how they cause disease. L. pneumophila possesses genes that are able to “trick” eukaryotic cells into transporting them to the endoplasmic reticulum; these virulence genes are called dot (defective organelle trafficking) or icm (intracellular multiplication). This dot/icm secretion system in L. pneumophila consists of 23 genes and is a type IV secretion system. Bacterial type IV secretion systems are bacterial devices that deliver macromolecules such as proteins across and into cells. After entry but before bacterial replication, L. pneumophila, residing in a membrane-bound vacuole, is surrounded by a ribosome-studded membrane derived from the host cell’s ER and mitochondria. Thus, by exploiting host cell functions, L. pneumophila is able to gain access to the lumen of the ER, which supports its survival and replication where the environment is rich in peptides. A second type II secretion system has also been implicated in the virulence of some strains of Legionella. The type II secretion system carries numerous genes for enzymatic degradation including lipases, proteinases, and a number of novel proteins. Mutations within the type II secretion system results in decreased infectivity of the organism. A number of additional bacterial factors have also been identified as crucial for intracellular infection; some of these are listed in Box 35-2. Legionella spp. are associated with a spectrum of clinical presentations, ranging from asymptomatic infection to severe, life-threatening diseases. Serologic evidence exists for the presence of asymptomatic disease, because many healthy people surveyed possess antibodies to Legionella spp. Table 35-1 provides a more detailed description of the following three primary clinical manifestations: TABLE 35-1 Disease Spectrum Associated with Legionella sp. From Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R: Principles and practices of infectious diseases, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2010, Elsevier. • Pneumonia with a case fatality rate of 10% to 20% (referred to as Legionnaires’ disease) • Pontiac fever, which is a self-limited, nonfatal, influenza-like respiratory infection • Other rare extrapulmonary sites, such as wound abscesses, encephalitis, or endocarditis.

Legionella

General Characteristics

Pathogenesis and Spectrum of Disease

Epidemiology

Disease

Pneumonia (Legionnaires’ Disease)

Community and nosocomial transmission (inhalation of aerosolized particles); immunocompromised patients, particularly in cell-mediated immunity; rarely occurs in children

Acute pneumonia indistinguishable from other bacterial pneumonias; clinical syndrome may include nonproductive cough, myalgia, diarrhea, hyponatremia, hypophosphatemia, and elevated liver enzymes

Pontiac Fever

Community setting associated with employment (industrial or recreational) or other group

Self-limiting, febrile illness; symptoms may include cough, dyspnea, abdominal pain, fever, and myalgia; pneumonia does not occur

Extrapulmonary

Rare, metastatic complications from underlying pneumonia; incidents of inoculation into sites via punctures have been identified or therapeutic bathing; highly associated with immunocompromised patients

Abscesses have been identified in the brain, spleen, lymph nodes, muscles, surgical wounds, and a variety of tissues and organs

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine