Chapter 3 After studying this chapter, the learner will be able to: • Define negligence as it applies to caregivers. • Describe the importance of patient care documentation. • List several methods of documentation of patient care. • Identify three potential events that could lead to litigation. • Describe the role of TJC in the promotion of patient safety. Competent patient care is the best way to avoid a malpractice or negligence claim. Unfortunately, even under the best of circumstances, a patient may be injured and recover monetary damages as compensation. Understanding how a liability action starts and how it proceeds is important in the effort to avoid the many pitfalls that can lead to being named and successfully sued in a lawsuit. 1. Duty to deliver a standard of care directly proportional to the degree of specialty training received 2. Deviation from that duty by omission or commission 3. Direct causation of a personal injury or damage because of deviation of duty 4. Damages to a patient or personal property caused by the deviation from the standard of care • Become active within the professional organizations associated with setting the standards for practice. Most organizations provide up-to-date education and resources for improvement of practice. Have a voice in shaping the future of the profession. • Remain current with continuing education. Become certified, and maintain the credential. • Establish positive rapport with patients. Patients are less likely to sue if they perceive that they were treated with respect, dignity, and sincere concern. Patients have the right to accurate information and good communication. • Comply with the legal statutes of the state and standards of accrediting agencies, professional associations, and the health care facility policies. • Adhere to the policies and procedures of the facility. Seek a position on the policy and procedure committee in order to have a say in the formation and revision of facility practices. • Document assessments, interventions, and evaluations of patient care outcomes. Leave a paper trail that is easy to follow for the reconstruction of the event in question. • Prevent injuries by adhering to policies and procedures. Shortcuts can be hazardous to the patient and team members. • If an injury occurs, control further injury or damage by reporting problems and taking corrective action immediately. • Maintain good communications with other team members. • In addition to these strategies, the facility as the employer and the caregiver as the employee should take steps to avoid liability. The facility protects the patient, its personnel, and itself by maintaining safe and well-defined policies and procedures based on national standards and recommended practices. • The contractor must be appropriately credentialed for the role. • The contractor must be competent. • The contractor must be providing care under the direct supervision of a licensed practitioner. • The contractor may perform duties only within the scope of his or her intended role. • The contractor must adhere to the policies and procedures of the facility. • The contractor must be oriented to the facility’s emergency evacuation procedures. • The contractor must be current in immunizations and health screenings. • The contractor must display appropriate identification at all times. • The contractor must comply with all background checks, possibly including fingerprinting and drug testing. 1. The type of injury would not ordinarily occur without a negligent act. 2. The injury was caused by the conduct or instrumentality within the exclusive control of the person or persons being sued. 3. The injured person could not have contributed to negligence or voluntarily assumed risk. • Screening and verifying qualifications of all staff members, including medical staff, according to standards established by TJC • Monitoring and reviewing performance and competency of staff members through established personnel appraisal and peer review procedures • Maintaining a competent staff of physicians and other caregivers • Revoking practice privileges of a physician and other caregivers when the administrators know or should have known that the individual is incompetent or impaired Some patients, such as celebrities, may request to be admitted with an alias. Care is taken when identifying these patients so that they will not be confused with other patients and receive the wrong procedure. Community hospitals may be admitting people from the surrounding neighborhood. The caregiver may be in a position to learn private information about a neighbor. Maintaining the confidentiality of patient information is imperative. Every health care worker has a moral obligation to hold in confidence any personal or family affairs learned from patients. Many facilities have implemented confidentiality agreements with all health care personnel on the premises. Schools for surgical personnel require students to sign confidentiality agreements before going to a clinical site. An example of a college confidentiality agreement can be found at http://evolve.elsevier.com/BerryKohn. HIPAA was published in the Federal Register in 2003 and the final rule took effect in April 2005. This act provides for confidentiality of health data involved in research or transmitted and stored by electronic or any other means. The release or disclosure of this protected health information (referred to as PHI) requires patient authorization. HIPAA covers far more than PHI—it covers fingerprints, voice prints, and photographic images.a TJC developed and approved a list of sentinel events that should be voluntarily reported and other events that need not be reported (Box 3-1). The TJC publication Conducting a Root Cause Analysis in Response to a Sentinel Event has been made available to institutions as a guideline for investigating the causes of sentinel events. The objective is to improve the system that has permitted the error to occur. Guidelines include a fill-in-the-blank questionnaire to help track the cause of the event. The guidelines suggested by TJC allow each facility flexibility in determining the root causes for events specific to the environment. Using flowcharts, the facility can identify one or more of these root causes. Each facility is encouraged but not required to report sentinel events to TJC. Other sources, such as the patient, a family member, or the media, may generate the report. If TJC becomes aware of an event, the facility is required to perform a root cause analysis and action plan or other approved protocol within 45 days of the event. A TJC glossary of sentinel event terminology can be viewed at www.TheJointCommission.org. The Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Act of 2005b encourages a culture of safety in the health care system. TJC indicates that mistakes are minimized by designing systems that anticipate and possibly prevent human error.c Each procedure has inherent safety risks that are not always apparent. These tend to surface when systems thinking is not foremost in the procedure development process. The 2005 act references data that show the incidence of reporting to be more accurate when done on a voluntary basis rather than when reporting is mandatory. Health care facilities have requested protection for reporting information because in order to rework the system the faults need to be known. This is the main way of studying problems and finding solutions for improved performance. Many states have adopted the National Quality Forum’s (NQF) list of 28 adverse events as the foundation for mandatory adverse event reporting.d In 2004, Minnesota was the first state to adopt the adverse events list as mandatory to report. In the first year of mandatory reporting, surgical adverse events were the highest reported of all the categories by early 2006. Other states have followed by implementing reporting systems and including additional categories of adverse events that are mandatory to report. For additional information about the NQF adverse event list, go to www.qualityforum.org. Universal Protocol is incorporated into the sixteen National Patient Safety Goals implemented in July, 2010 by the Joint Commissione (Fig. 3-1). The following Joint Commission accreditation statements incorporate NPSGs’ language to prevent wrong patient, wrong site, and wrong surgery events as part of Universal Protocol:

Legal, regulatory, and ethical issues

Liability

Liability prevention for the facility and the team

Independent contractor

Doctrine of res ipsa loquitur

Doctrine of corporate negligence

Invasion of privacy

Health insurance portability and accountability act (HIPAA)

TJC and sentinel events

Root cause analysis

Institutional reporting of sentinel events

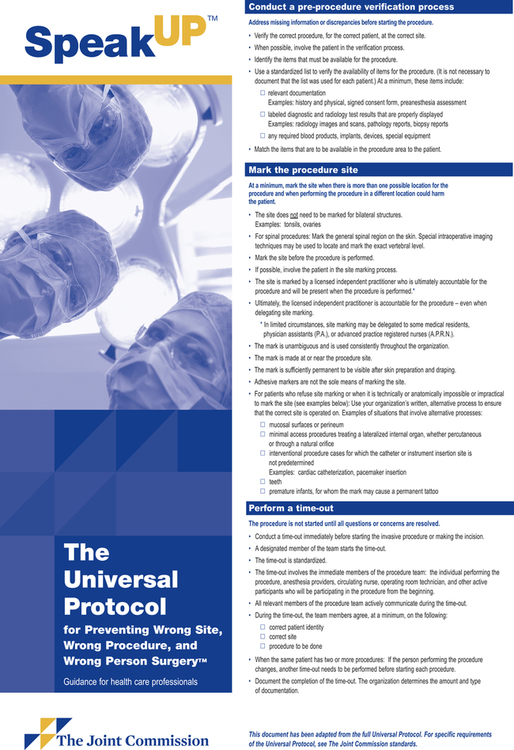

National patient safety goals (NPSGS)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Legal, regulatory, and ethical issues

Website

Website