Left Hepatic Lobectomy

Jon S. Cardinal

DEFINITION

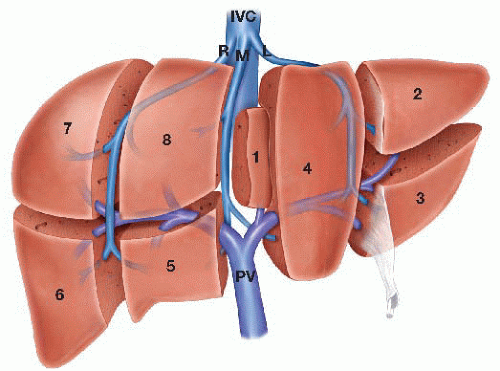

The liver has a segmental anatomy that is defined by the intrahepatic distribution of the portal triad structures. There are eight liver segments (FIG 1) with the left hepatic lobe being constituted by segments 2 to 4 and the right lobe being constituted by segments 5 to 8. Segment 1, the caudate lobe, which is distinct from both the left and right lobes.

The boundary between the right and left lobes of the liver is an imaginary line, known as Cantlie’s line, which runs from the gallbladder anteriorly to the inferior vena cava (IVC) posteriorly.

Left hepatic lobectomy is considered a major anatomic liver resection and is defined by the removal of the liver segments that constitute the left hepatic lobe (2 to 4).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Indications for left hepatic lobectomy include both benign and malignant etiologies, neoplastic and nonneoplastic processes, and conditions that are either primary or secondary to the liver itself.

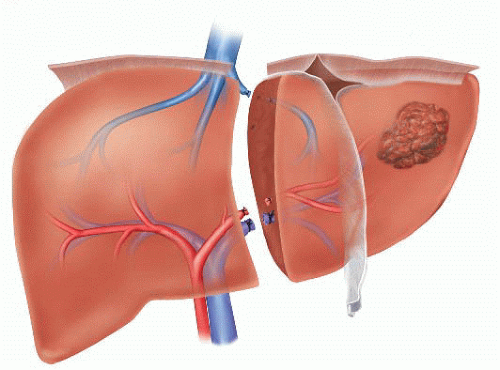

Generally, left hepatic lobectomy will need to be performed when the condition that is being treated requires division of any (or all) of the major inflow (portal vein, hepatic artery) and/or outflow (left or middle hepatic vein, left hepatic duct) structures to the left lobe of the liver (FIG 2).

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The single biggest preoperative factor to account for when considering patients for major anatomic liver resection, including left hepatic lobectomy, is the health of the native background liver.

In a patient with a healthy background liver, anatomic trisegmentectomy can be performed and tolerated; however, in patients with chronic liver disease of any kind, the extent of resection needs to be carefully weighed against the possibility of postoperative liver insufficiency and/or failure.

Among others, historical factors that may indicate the presence of underlying chronic liver disease include accurate quantification of alcohol use (current and past); identification of risk factors for viral hepatitis exposure (intravenous [IV] drug abuse, tattoos, promiscuous sexual behavior, history of blood transfusions); comorbidities that predispose to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NALFD) such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and high cholesterol; prior chemotherapy exposure(s) in cases of patients who are being considered for liver resection for oncologic purposes, the type and duration of which can predispose to chemotherapy-associated steatohepatitis (CASH); and past history suggestive of liver decompensation including prior episodes of jaundice, gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, ascites production, and so forth.

Findings on physical examination of the stigmata of cirrhosis are indicative of advanced chronic liver disease and are generally considered as contraindications for major liver resection (Table 1).

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Standard blood work including a complete blood count, complete metabolic panel, and coagulation panel are required prior to proceeding with any major liver surgery.

When the history and/or physical examination points to a chronic, underlying liver disease, additional serologic testing for any of the viral hepatitides as well as other obscure causes of cirrhosis (hemochromatosis, Wilson’s disease, etc.) may be advisable. In cases of liver tumors, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), α-fetoprotein (AFP), and/or carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) levels occasionally can provide diagnostic clarity and therefore should routinely be obtained.

Table 1: Clinical History and Physical Examination Findings Associated with Cirrhosis

History

Fatigue or weight loss

Jaundice (icterus; skin, urine, and stool color)

Anorexia, cachexia

Abdominal pain

Edema

Ascites

GI bleeding, hemorrhoids

Loss of libido or menstrual cycle

Encephalopathy

Physical Examination

Malnutrition

Fetor hepaticus

Jaundice, scleral icterus

Spider angiomata

Clubbing, palmar erythema

Gynecomastia, testicular atrophy

Ascites

Abdominal hernia

Caput medusa

Hepatosplenomegaly

Asterixis

GI, gastrointestinal.

Ultrasonography can identify cirrhotic liver morphology by providing information on the size, contour, and echotexture of the liver. While this modality has the advantage of being noninvasive, it is also highly operator dependent.

When planning major liver surgery, high-quality crosssectional imaging is a prerequisite. Either computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used. Contrast enhancement, which should include both an early hepatic arterial phase as well as a delayed portal venous phase (so-called liver protocol scan), is the best manner in which to obtain detailed images of the liver as well as the relationship of tumor(s) to the major intra- and extrahepatic structures.

Additionally, liver protocol scans can, in some instances, obviate the need for invasive biopsy and the risks associated therein due to the fact that certain liver tumors including simple cysts, hemangioma, focal nodular hyperplasia, and hepatocellular carcinoma have radiographic appearances that can be diagnostic in the appropriate clinical setting.

MRI/magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) may be preferred in cases in which bile duct resection/reconstruction is a possibility, as this modality provides superior anatomic definition of the biliary anatomy in comparison to CT scan alone.

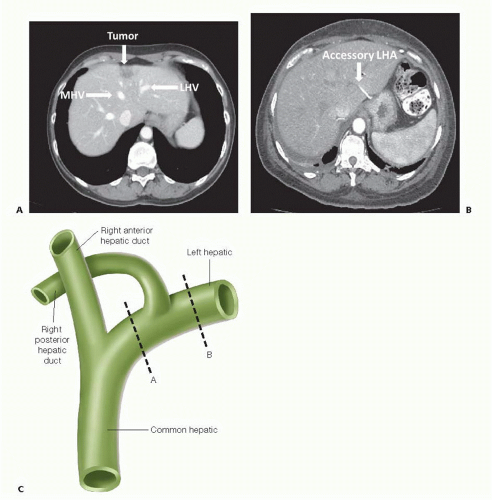

Specifically, in regard to left hepatic lobectomy, careful attention should be paid to the relationship of any tumor(s) within the left lobe to the left hilar structures as well as the left hepatic vein and/or common trunk (FIG 3A). Welldescribed anatomic variants, such as a replaced or accessory left hepatic artery (FIG 3B) or a right posterior hepatic duct arising from the main left hepatic duct (FIG 3C), should be carefully evaluated for as their presence may alter the conduct of the operation.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

The most important step prior to performing any major liver operation is thorough and careful review of the available preoperative imaging studies. Understanding the relationship of tumor to major intra- and extrahepatic structures allows the surgeon to anticipate and plan strategies for dealing with point(s) during the parenchymal transection that may be challenging or where close margins may be anticipated.

Adequate preparation for major liver surgery involves having blood available (two to four units of crossmatched packed red blood cells [PRBCs]) in the event of intraoperative hemorrhage.

Preoperative discussion with the anesthesiologist is advisable with important points of consideration to include possible epidural or paravertebral nerve block placement for perioperative analgesia as well as choosing which invasive monitoring devices will be required. For left hepatic lobectomy, it is recommended that a central venous catheter be placed so that low central venous pressure (CVP) (5 mmHg or less) can be maintained up until the point that the parenchymal transection is complete. Additionally, arterial line placement is warranted. A nasogastric tube (NGT) for gastric decompression is recommended.

Positioning

For left hepatic lobectomy, patients should be positioned supine with the arms out on arm boards at 60 degrees. The area to be prepped and draped starts cranially at the nipple line, extends caudally to the symphysis pubis, and laterally carries down to the table on both sides. A Foley catheter is required, and both lower and upper body forced air heated blankets should be applied to maintain normothermia.

FIG 3 CT scan showing the relationship of a metastatic colorectal cancer tumor deposit to the middle hepatic vein (MHV) and left hepatic vein (LHV), respectively. B. CT scan showing an accessory left hepatic artery (LHA) coming off of the left gastric artery and coursing through the gastrohepatic ligament. C. Drawing showing the right posterior (RP) sectoral duct arising from the left hepatic (LH) duct. When this anatomic variant exists during a left hepatic lobectomy if the LH duct is transected in plane A, the RP segments (6 and 7) will be disconnected from the biliary tree. If the LH duct is transected in plane B, the RP ducts will remain connected to the main biliary tree and be able to drain.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|