Chapter 31 Learning the language of clinical reasoning

In this chapter we argue the case for a discursive view of clinical reasoning. We contend that becoming proficient at clinical reasoning is in large part a process of mastering, in particular, the language of a health profession and more broadly the language of healthcare systems. In learning to become competent in clinical reasoning, new practitioners must master a number of aspects of language; these include terminology, category systems, metaphors, heuristics, rituals, narrative, rhetoric and hermeneutics (Loftus 2006, Loftus & Higgs 2006). This interpretive view of clinical reasoning is in contrast to the current and more widespread view that clinical reasoning is, or should be, regarded as a phenomenon of computational logic and symbolic processing, combined with probability mathematics and statistics. The latter view is based within a more empirico-analytical paradigm and, we argue, is less useful as a conceptual model of clinical reasoning and how people come to learn this specialized skill. We draw both on the literature and on recent research (Loftus 2006) that utilized hermeneutic phenomenology to explore the nature of clinical decision making and how it is learned.

THE CENTRALITY OF LANGUAGE

Perhaps the most distinguishing feature of human beings is their use of language. A major problem with discussing language and its role in clinical reasoning is that for too many people language is mistakenly viewed as nothing more than a passive conduit by which meaning is transferred from the mind of one person to another. This is open to challenge. It can be argued that it is language that makes us human (Gadamer 1989). Language is central to human nature and to being human. Being immersed in a world of language allows us to construct meaning intersubjectively through the dialogue and interaction we have with others (Bakhtin 1986). The implication is that to understand reasoning of any kind, including clinical reasoning, we need to study the ways in which practitioners employ language and interaction to address clinical problems, rather than assuming that practitioners use objective mathematical methods to cope with tasks such as diagnosis.

In arguing for exclusively mathematical methods, Descartes (trans. Clarke 1999) made the error of rejecting Aristotle’s notion that different fields of knowledge require different methods and different means of proof. Aristotle (trans. Lawson-Tancred 1991) asserted that mathematical proofs normally have no place in a speech meant to persuade others. It can be argued that clinical reasoning is largely a matter of persuading oneself and others that a particular diagnosis and management plan is correct. Clinical reasoning is therefore a discursive construction of meaning, negotiated with patients, their carers, other health professionals, but above all with oneself. To become proficient at clinical reasoning, health professionals must therefore become proficient in the language skills required to persuade people.

LANGUAGE SKILLS OF CLINICAL REASONING

In recent doctoral research Loftus (Loftus 2006, Loftus & Higgs 2006) sought to gain a deeper understanding of the place of language in clinical reasoning. He studied settings where health professionals and medical students engaged in clinical decision making in groups, including problem-based learning (PBL) tutorials and a multidisciplinary clinic.

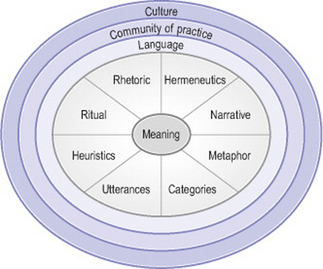

The research showed that clinical reasoning can be visualized as a quest for meaning, using the language tools that are part of the interpretive repertoire provided by the community of practice called a health profession. That is, communities of practice provide both the interpretive frames of reference and the language tools for meaning-making by their members. When working in these communities, health professionals need to learn a range of language skills to be used for clinical reasoning. These are represented in Figure 31.1. The skills include knowledge of, and ability to use, appropriate terminology, categories and category systems, metaphors, heuristics and mnemonics, ritual, narrative, rhetoric and hermeneutics. All these skills need to be coordinated, both in constructing a diagnosis and management plan and in communicating clinical decisions to other people, in a manner that can be judged intelligible, legitimate, persuasive, and as carrying the moral authority for subsequent action.

TERMINOLOGY/KEY WORDS

Mastering the terminology of a health profession is a basic skill in clinical reasoning, which forms the foundation for the other skills required. This is a matter not just of knowing particular words and phrases, but more importantly, of knowing how and when to use them appropriately. For example, one medical student spoke of acquiring basic skills in psychiatry:

it [psychiatry] has its own little language for speaking to itself and you don’t pick up on that unless you’re using it every day in a group talking to someone … we’d see patients together and we’d discuss the patients and run through it using our little list of jargon terms. … So you got used to using the language and when it came time to sit your exam you felt quite comfortable. (Loftus 2006, p. 140)

CATEGORIES

Many student participants in Loftus’s (2006) study found that a practice-based method of learning such as PBL gave them familiarity with a clinico-pathological category system that lent itself naturally to clinical practice. As one student observed, ‘This year I’ve realized how helpful they [PBL tutorials] are because it gives you that approach to thinking about things in categories’ (p. 143).

Many novice health professionals begin their clinical education already having learned the category systems of the basic medical sciences, and they find that these scientific categories can be quite different from the more practical categories of the real world of health professional practice. One student spoke of having to reorganize his knowledge in a case-based manner so that it was more fitting for the practice of medicine: ‘I’ve gone through my old notes and progressively thrown them out as I’ve rewritten them into a different format … now I approach learning the diseases in the same way that I would … a patient’ (Loftus 2006, p. 145). In other words, his biomedical knowledge was being reframed around patient narratives he had come across in clinical practice. The category systems used in clinical reasoning need to be appropriate for the practice situation. For example, typical diagnostic categories used by a doctor in chronic pain management were described thus: ‘I think in three components. One is nociceptive … and a neuropathic component … [and thirdly] … psychosocial contributors’ (p. 146). A clinical psychologist, working in the same setting, spoke of three different categories: thought, feelings and behaviour. Categories provide a foundation for metaphors used in clinical reasoning.

METAPHOR

Lakoff & Johnson (1980) argued that thought and language are fundamentally metaphorical. Metaphor is not simply an embellishment of language exploited by writers and poets. It can be argued that language and thought are intensely and inherently metaphorical and, because of this, metaphor use goes largely unnoticed as it is so completely natural to us (Ortony 1993). In recent years there has been a growing recognition of the extent to which metaphor underlies scientific and medical practice and shapes the ways in which both health professionals and their patients conceptualize their health problems and what can be done about them (e.g. Draaisma 2001, Reisfield & Wilson 2004).

A key metaphor underlying the biomedical model is ‘The body is a machine’. This is also the underlying metaphor through which patients in Western societies tend to conceptualize their bodily problems (Hodgkin 1985). The implication of this metaphor is that we can always, in principle at least, repair a broken machine. In acute care this metaphor could be appropriate. However, the metaphor frequently falls down in the chronic situation where repeated attempts at repair fail, resulting in frustration and disappointment for both patients and health professionals. Often such patients are ‘discarded’ by the system as ‘failed’ patients (Alder 2003).

In the Loftus (2006) study the ways in which the staff of the multidisciplinary pain centre described their work indicated that the metaphors at work were more in keeping with caring for chronic patients. For example, one metaphor that suggested itself repeatedly was ‘Life is a journey’. Rather than trying to cure patients, the staff provided interventions, from dorsal column stimulators to cognitive behavioural therapy, to help patients adjust their lives so that they could continue living a relatively normal life despite pain.

HEURISTICS/MNEMONICS

Heuristics and mnemonics are language tools that enable health professionals to manage an enormously complex and growing body of knowledge in ways that best suit the clinical reasoning required when dealing with patients in the real world. Student participants in the Loftus (2006) study who made maximum use of mnenonic and heuristic tools claimed that assessing complex cases became relatively straightforward. Typical mnemonics include the well-known VITAMIN D memory aid used to assist novices in remembering the various disease categories. This particular mnemonic stands for Vascular, Infectious, Traumatic, Autoimmune, Metabolic, Inflammatory/Idiopathic, Neoplastic and Drug-related. Another mnemonic is Dressed In A Surgeon’s Gown, Most Physicians Invent Diagnoses. This translates to: definition, incidence, aetiology, sex, geography, macroscopic/microscopic changes, presentation, investigation, drug treatment. For students, the PBL format itself can provide a heuristic for assessing patients. Medical students in the programme studied reported that by the third year they were entirely familiar with the PBL format. Most reported using the PBL format when assessing real patients, as they believed it was both a rigorous and a comprehensive approach to clinical reasoning. One student reflected: ‘I think it’s a really good idea. It’s how you think clinically’, and she was also persuaded of its normative nature: ‘it’s how you should think clinically’ (p. 166).

Health professionals assessing complex chronic pain cases certainly found that they needed some format to guide assessment. As one physiotherapist said about teaching students: ‘I encourage them [the students] to have a format to start with, because you can get lost with these patients because they can go off on many tangents’ (Loftus 2006, p. 170). Heuristics and mnemonics also tend to be used in a ritualistic manner.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree