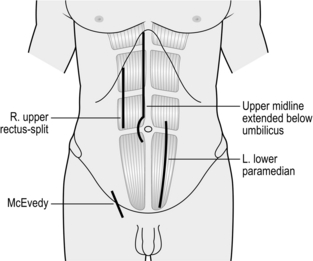

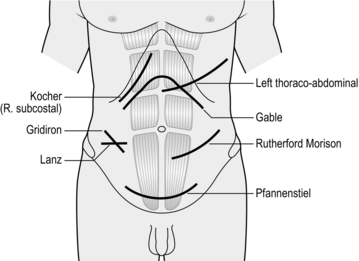

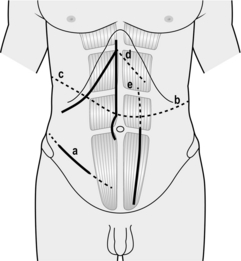

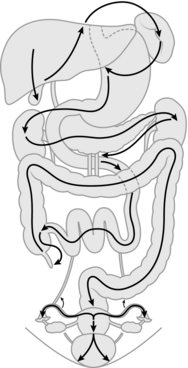

4 Laparotomy (from the Greek laparos = soft, referring to the abdomen) is a skill every surgeon caring for general surgical patients should possess and master to a level which makes him or her confident to perform whenever called upon. The approach to a patient with abdominal pathology has undergone significant changes due to advances in both diagnostic techniques and treatment options. Rapid progress in endoscopic and imaging techniques has led to better preoperative assessment of the abdomen, thereby enabling surgeons to make a more confident decision on the necessity and timing of laparotomy. Minimal access surgery (laparoscopy) has added to the repertoire, aiding both in diagnosis of the acute abdomen1 and in therapeutic procedures. As a result of these changes diagnostic laparotomy is now a rarity. Better understanding of many disease processes, such as peptic ulcer and pancreatitis, and improvements in their pharmacotherapy have led to a significant decrease in patients undergoing laparotomy for these conditions. Surgical approaches to the abdomen are undergoing continuous change and procedures such as single incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS)2 and natural orifice endoscopic surgery (NOTES),3 whilst still in their infancy, are gaining popularity. 1. Ideally, see the patient in the ward before their arrival in the operating theatre. Explain the procedure along with the options available and associated risks. Clearly explain any possibility of additional procedures to ensure informed consent. Review the case notes and arrange to display relevant imaging in the operating room. 2. The WHO surgical safety checklist4 is now universally employed in the UK and in many other countries. Follow it meticulously in every case to prevent mishaps arising from human error. 3. Give prophylactic antibiotics at this stage (if not already started), according to hospital guidelines.5 4. Palpate the patient’s abdomen after induction of general anaesthesia. Previously impalpable or indistinct masses may be more evident, such as an appendix mass or empyema of the gall bladder, or less evident, for example an incisional hernia that has spontaneously reduced following muscle relaxation. 5. Consider the patient’s position on the operating table before commencing the procedure. If a lateral tilt is required, secure the patient adequately. Employ a Lloyd-Davies position for all procedures likely to involve the pelvic organs or left colon, to allow access to the rectum. 6. Prepare the skin with an antiseptic solution such as 10% povidone-iodine, 1:5000 chlorhexidine or 1% cetrimide, provided there is no known allergy to any of these agents, using a swab on a sponge holder.5 For a laparotomy, prepare the skin from the nipples to the mid thigh. Alcohol-based antiseptics give superior bactericidal results, but remove any excess (which often pools around the flanks) if diathermy is to be used on the skin or subcutaneous tissues to prevent burns. 7. Drape the patient with sterile drapes, adequately exposing the area of interest. An adhesive plastic drape, such as Opsite™ or Steridrape™ may be used on the exposed skin after the drapes are placed. Make the skin incision through this adhesive drape. 1. Principles influencing the choice of incision are adequate exposure, minimal damage to deeper structures, ability to extend the incision if required, sound closure and, as far as possible, a cosmetically acceptable scar. Placement of stomas and the need to access the abdomen quickly may also dictate the choice of incision: thus for abdominal trauma and major haemorrhage always use a midline incision. 2. Placement of the incision depends on the planned procedure: a roof top incision is ideal for surgery on the liver, a left subcostal incision for an elective splenectomy and McBurney’s incision for appendicectomy. Cosmesis is important, but not at the cost of adequate, safe exposure of the relevant structures. Consider achieving a sound repair at the end of the procedure at this stage. There is no conclusive evidence that transverse incisions heal better than vertical incisions but reports support a non-statistical advantage for the former.6 3. Midline laparotomy (Fig. 4.1) is the default incision for most procedures on the abdomen: the extent will vary according to the exposure required. The incision traverses a relatively avascular field (the linea alba). As the peritoneum is exposed, the falciform ligament comes into view in the upper abdomen. This can be ligated and divided or avoided by deepening the incision to one or other side of the ligament. Curve the incision around the umbilical cicatrix to avoid dividing it. Close the midline incision by a single layer mass closure technique using No.1 nylon, polypropylene or PDS. In the lower one-third of the abdomen the posterior rectus sheath is deficient: ensure adequate bites of tissue when closing this part of the incision. 4. Paramedian incision (Fig. 4.1). This gives comparable exposure to the midline incision but is time-consuming to create and close, gives an inferior cosmetic result and carries a greater risk of postoperative dehiscence, therefore use a midline incision wherever possible. Make the skin incision 2–3 cms lateral to the midline and incise the anterior rectus sheath along the skin incision. Retract the rectus muscle laterally and incise the posterior rectus sheath and peritoneum in the midline. Close the abdomen in layers: close the peritoneum and the posterior rectus sheath either with Vicryl, PDS, polypropylene or nylon. Allow the rectus muscle to fall back in place and close the anterior rectus sheath. Perform skin closure as usual. 5. Oblique subcostal incisions (Fig. 4.2) are used to access the upper abdomen, for example the liver and gall bladder on the right (Kocher’s incision, after the Nobel prize winner Theodore Kocher, 1841–1917) and the spleen on the left. They may be extended across the midline as a roof top incision if required, for example, in surgery of the liver and pancreas. Make the incision over the area of interest, about two finger breadths below the subcostal margin and towards the xiphisternum. Deepen the incision to expose the external oblique and the anterior rectus sheath. Divide these layers and the rectus muscle and incise the internal oblique muscles with diathermy. It is helpful to insert a long artery forceps such as Robert’s or Kelly’s under the muscle belly to facilitate this. Divide the posterior rectus sheath and transversus abdominis aponeurosis to expose the pre-peritoneal fat and open the peritoneum in line with the incision. Take care to spare the ninth costal nerve, which is visible at this stage. A midline superior extension through the linea alba to form a ‘Mercedes Benz’ incision provides further access if required. 6. The Rutherford Morrison (1853–1939) incision (Fig 4.2) starts about 2 cm above the anterior superior iliac spine and extends obliquely down and medially through the skin, subcutaneous tissues and external oblique along its fibres, cutting the underlying internal oblique and transversus abdominis and the peritoneum along the line of the skin incision. Use an extra-peritoneal approach to place a transplanted kidney in the iliac fossa or to expose the iliac artery during vascular operations. Use a shorter incision, centred over McBurney’s point and splitting the external oblique, internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles along the direction of the fibres (the grid iron incision) in conventional appendicectomy. This incision can be extended laterally and medially if required to convert into a Rutherford Morrison incision. 7. Transverse incisions (Fig. 4.2) provide the best cosmetic scars. They can be used above or below the umbilicus depending on requirements. Ramstedt’s pyloromyotomy and transverse colostomy are performed via incisions above the umbilicus. Lanz incision (Otto Lanz, 1865–1935) is used for appendicectomy and the Pfannenstiel incision (Hermann Johannes Pfannenstiel, 1862–1909) is used for operations on the uterus, urinary bladder and the prostate. The Pfannenstiel incision is a slightly curved horizontal incision about 2–3 cm above the pubic symphysis. Incise the anterior rectus sheath along the skin incision and retract the rectus and the pyramidalis muscles laterally. Incise the peritoneum vertically. Close the peritoneum in the midline using polyglycolic acid sutures and close the rectus sheath with polypropylene, PDS or nylon. The Lanz incision starts 2 cm below and medial to the right anterior superior iliac spine and extends medially for 5–7 cm. The rest of the exposure is similar to the grid iron incision.7 8. Thoraco-abdominal incisions usually follow the line of a rib and extend obliquely into the upper abdomen, dividing the cartilaginous cage protecting the upper abdominal viscera. Alternatively, you may convert a vertical upper abdominal incision into a thoraco-abdominal approach by extending it in the line of a rib across the costal margin. Radial incision of the diaphragm towards the oesophageal hiatus (left) or vena cava (right) converts the abdomen and thorax into one cavity and provides unparalleled access for oesophago-gastrectomy and right hepatic lobectomy. Thoraco-laparotomy may also be indicated for removal of a massive tumour of the kidney, adrenal or spleen. 9. Posterolateral incisions for approach to the kidney, adrenal and upper ureter are described in the relevant chapters. 1. Make the incision with the belly of a no. 20/22 scalpel, holding the knife as you would a table knife and using controlled movements. Once you have cut the skin pass the knife back to the scrub nurse in a kidney dish. 2. Alternatively, use a cutting diathermy spatula. Despite early concerns that the use of diathermy to incise skin and subcutaneous tissue might affect wound healing, it provides superior haemostasis and does not appear to adversely influence wound infection or cosmesis. 3. Deepen the incision using either a scalpel or cutting diathermy spatula. Control any ensuing bleeding from subcutaneous or intramuscular vessels with forceps and diathermy or suture. Use a unipolar or bipolar diathermy forceps, taking care not to burn the adjacent skin. Ligate vessels larger than 2 mm with an absorbable suture. 4. Apply wound towels to the wound edges and clip the tails of these towels with a Dunhill clip so that they are not lost. Change these towels if they become contaminated with infected abdominal contents. 5. Cut, split or retract the muscles of the abdominal wall as required and dictated by the incision that you use. Pick up the peritoneum with Dunhill or Fraser-Kelly artery forceps and tent it up to ensure no bowel is caught. Incise the tented peritoneum to enter the abdominal cavity. In patients with intestinal obstruction, bowel may lie close to the peritoneal incision or, in case of a previous laparotomy, may be adherent to it. Take the utmost care to avoid making an enterotomy which, even if noticed and repaired, may result in subsequent complications. 1. If the previous incision coincides with the site chosen for present access, use it. If not, use a new incision. 2. A longer incision may be required than was necessary for the initial operation. 1. If the old scar is acceptable make your incision through this without any attempt to excise it. If the scar is ugly or stretched, excise it by making an incision on either side of the scar. 2. For a paramedian scar the dissection is deepened in the line of the skin incision without any attempt to dissect the rectus sheath. 3. Open the peritoneum with great care as adhesions are common and bowel is often adherent to the old scar. It is wise to approach a virgin area first (hence a longer incision than before), then proceed towards the scarred area. Another alternative is to open the peritoneum to one side of the previous scarring and then dissect the scarred area under direct vision. Time spent here is amply justified. 4. Plan a secure closure at the time of the incision, as in a first-time laparotomy. Make sure that adequate abdominal wall and peritoneum remain and are free of adherent viscera. 1. Adhesions occur in 90–95% of patients undergoing an invasive procedure on the abdomen, irrespective of the operative approach.8,9 They are a cause of much morbidity: 35% of patients with a prior laparotomy will be re-admitted to hospital an average of two times with adhesion-related complications.10 In 1992, a UK survey reported 12 000 to 14 400 cases of adhesive small-bowel obstruction annually; in the USA in 1988, 950 000 days of inpatient care were required for adhesiolysis at a cost of 1.18 billion dollars.11 2. Intra-abdominal trauma or invasion of the peritoneal cavity, infection, bleeding and foreign material (glove powder, fibre from surgical swabs, suture materials, etc.) and intra-peritoneal chemotherapeutic agents are all thought to be responsible for increased formation of adhesions. 3. The most frequent sites are omentum (68%), small-bowel (67%), abdominal wall (45%) and colon (41%). 1. Meticulous haemostasis, prevention of intra-peritoneal spillage of intestinal contents, minimal handling of bowel, use of powder-free gloves, glove cleansing using a 10% solution of povidone-iodine in a non-toxic detergent base and not closing the peritoneum have all been advocated to prevent adhesion formation. 2. Seprafilm™ (hyaluronate-carboxymethyl cellulose membrane, Genzyme) has been reported to reduce the incidence of adhesions and the number of patients requiring surgery for small-bowel obstruction. However, the incidence of intra-abdominal abscesses and anastomotic leaks was higher in the Seprafilm group compared to controls. Adept™ (icodextrin 4% solution) has been shown to be safe and effective in reducing adhesions during laparoscopy. Interceed™ (oxidized regenerated cellulose, Johnson & Johnson) is another anti-adhesion barrier that has gained popularity among gynaecological surgeons. None, however, have found widespread acceptance, due in part to their cost. A cheaper alternative is liberal irrigation with Ringer lactate solution, which has been reported to decrease adhesions in experimental animal models. 1. It is futile to divide every single adhesion as, once divided, they are likely to form again, so divide adhesions only if they are causing a problem. Patients with recurrent adhesive small-bowel obstruction benefit from adhesiolysis and restoration of the bowel anatomy. However, it may be safer to leave the adhesions alone when they are dense but still allow intestinal contents to pass freely. 2. If in the process of releasing the adhesions the bowel is injured, perform a meticulous repair. Minimize contamination of the abdominal cavity by liberal suctioning and lavage. 3. The aims of the operation should be: 1. Exploration of the abdomen was used extensively and routinely in the past. Each time an abdomen was opened, the surgeon meticulously and methodically examined every organ to ascertain the cause of the patient’s symptoms. Improvements in diagnostic and imaging methods (in particular endoscopy and computed tomography) have made this unnecessary in most cases. However, exploration is still important in emergencies affecting the abdomen where a clear diagnosis may not be available due to the emergent nature and need to operate without thorough investigation. Knowledge of exploratory laparotomy is, therefore, still important, particularly for surgeons in training. 2. The advent of intra-operative ultrasound, endoscopic ultrasound and in some centres even on-table CT scan and angiography are welcome additions to the surgeon’s armamentarium and may improve the assessment of deeper organs and intraluminal pathology. However, these modalities are not widely accessible and even if the technology is available, the expertise may not be. 3. Despite advances in investigative technology, exploration of the abdomen is still occasionally carried out as an elective ‘final’ diagnostic procedure in patients with inexplicable, distressing or sinister symptoms. However, such instances are becoming increasingly rare: one such example is small-bowel tumours, which were traditionally confirmed at laparotomy but can now be diagnosed on capsule endoscopy. Diagnostic laparoscopy has largely replaced laparotomy in these difficult cases. 4. Symptoms arising from the abdominal wall may confuse the diagnosis. A careful examination performed with the abdomen relaxed and a trial of local anaesthetic may help. Beware of referred pain from the spine and Herpes Zoster infection. 5. In patients with suspected mesenteric ischaemia and possible intra-abdominal sepsis, make an early decision on operative intervention. Diagnostic laparoscopy in the former and a CT scan in the latter may be helpful. 1. The principles governing incisions were addressed at the beginning of this chapter and will be re-addressed in chapters dedicated to the relevant organs. When the diagnosis is in doubt select a midline incision, which is quick, versatile and allows access to the whole abdomen, which affords the luxury of almost unlimited extension from thoracic cavity to pelvis. Other incisions mentioned earlier may be used in specific conditions (Table 4.1). Table 4.1 Rutherford Morrison incisions to expose abdominal viscera 2. In patients with a previous laparotomy scar, favour the same scar to enter the abdomen, but not at the cost of urgency, exposure or safe closure. Try to avoid an area where a stoma will need to be sited. 3. When the findings on entering the abdomen are different from those suspected preoperatively, the incision may have to be extended or even closed and another incision made. For example, if a duodenal perforation is discovered at appendicectomy, the Lanz incision may have to be closed and a midline incision performed to facilitate appropriate surgery and adequate lavage of the abdomen. 4. Figure 4.3 displays the different techniques to extend incisions in order to deal with unexpected findings or intra-operative difficulties. 5. A wide range of retractors is available. The Goligher, Bookwalter and the Omni-tract retractors greatly facilitate access during a difficult laparotomy and should be kept available. Make sure they can be fixed to the operating table. Proper and liberal use of retractors frees an assistant to be used in other crucial steps. 6. Adjust the patient’s position when required to improve exposure to an organ or area. Tilt the patient away from the area of interest so that bowel falls away, giving a better exposure. This is particularly important in laparoscopic surgery where a tilt of about 20 degrees can make a great difference. 1. Have the theatre nurse clear all unnecessary instruments from the operative field. Transfer sharp instruments in a kidney dish and not directly, to avoid injuries. 2. Carry out a systematic examination of the abdomen and its contents by feel and visually after ensuring that lighting is optimal. It is recommended that a set sequence is followed in examining the abdominal viscera so that no structure is missed (Fig. 4.4): 3. Record the findings of this exploration in detail at the end of the operation. You may be able to dictate the findings to an observer for direct entry into the operation notes. 4. In the presence of a tumour it is usual to adopt a no touch or minimal touch technique, although there is no firm evidence that this improves survival.12 5. In emergency laparotomy immediate action may be required, for example to stop bleeding or close a perforation. Thereafter, perform a methodical examination of the other viscera unless the patient’s general condition precludes it. Note the nature and amount of any free fluid, collecting some for chemical, cytological and microbiological examination. 1. Make a decision on any definitive procedure: consider the preoperative diagnosis, operative findings and the patient’s condition. In elderly or sick patients control of the emergency condition takes precedence over the complete eradication of disease. Inform the anaesthetist as soon as you decide a course of action. 2. Incidental findings such as gallstones, diverticula, fibroids or ovarian cysts do not automatically call for action unless they pose an immediate threat to health or offer a better explanation for the patient’s symptoms than the original diagnosis. Similarly, during a laparotomy for another condition, do not perform an appendicectomy without an indication. The patient’s prior consent is unlikely to have been obtained, so any adverse outcome may be more difficult to defend. By contrast, ordinarily remove an unsuspected neoplasm, if necessary through a separate incision, provided the patient’s condition allows. Whatever course you adopt, meticulously record the findings in the operation notes. 3. The contents of the distal small-bowel and the entire large-bowel are unsterile. Visceral contents that are normally sterile such as bile, urine and gastric juice may also become infected as a result of inflammation and obstruction. Before opening the bowel or other potentially contaminated viscera, isolate the area from contact with the wound and other organs by using moist abdominal swabs. Apply non-crushing clamps to occlude the lumen and ensure that an efficient suction apparatus is available to remove any contents that spill. Following closure of the viscus discard all instruments and swabs used on opened bowel and change gloves. 4. The risk of infection depends on the degree of contamination. Healthy tissues can normally cope with a small number of organisms but are overwhelmed by heavy contamination or re-infection. Logically, reducing bacterial contamination reduces infection. 5. Patients with impaired local host defences, such as those on immuno-suppressants, steroids and diabetic patients, are susceptible to a wide range of organisms including fungi, particularly if they have previously had antibiotics. When there is gross infection (peritonitis) or spillage into the peritoneal cavity, liberally irrigate with warm saline or diluted povidone-iodine to reduce the bacterial load. 6. With the increased use of intestinal staplers, bowel clamps are infrequently used in some centres. It is, however, useful to know the types of bowel clamp and when they should be used. Intestinal clamps are of two types: crushing and non-crushing: 7. We are all familiar with stories of instruments and swabs left inside the abdomen and this represents one of the surgeon’s worst nightmares. There is no single routine that entirely guards against this mishap. Use the minimum number of instruments and the largest swabs, which should remain attached to large clips lying outside the abdominal wound. Avoid using small swabs deeply within the abdomen. If possible, use long-handled instruments on tissues and structures when prolonged use is anticipated. Although the primary responsibility of leaving a swab or an instrument in the abdomen rests with you as the operating surgeon, encourage the entire team to take an active role in preventing it. The scrub nurse counts the instruments and swabs before the procedure and before closure of the operative wound. He or she also counts any extra instruments, needles or swabs used during the procedure. If the scrub nurse reports a missing swab or instrument while closing the abdomen, carry out a thorough search of the abdomen and vicinity. If all else fails, perform an abdominal X-ray before waking the patient from the anaesthetic.

Laparotomy

elective and emergency

INTRODUCTION

OPENING THE ABDOMEN

Preparation

Incisions

Making the incision

RE-OPENING THE ABDOMEN

Appraise

Access through the old incision

ABDOMINAL ADHESIONS

Prevention of adhesions

Division of adhesions

EXPLORATORY LAPAROTOMY

Access

Midline

Upper

Hiatus, oesophagus, stomach, duodenum, spleen, liver, pancreas, biliary tract

Central

Small-bowel, colon

Lower

Sigmoid, rectum, ovary/tube/uterus, bladder and prostate (extraperitoneal)

Throughout

Aorta

Paramedian (incl. rectus split)

Upper

Biliary tract (right), spleen (left), etc.

Central

Small-bowel, colon

Lower

Pelvic viscera, lower ureter (extraperitoneal)

Oblique

Subcostal

Liver and biliary tract (right), spleen (left)

Gable (bilateral subcostal)

Pancreas, liver, adrenals

Gridiron

Caecum–appendix (right)

Rutherford Morison

Caecum–appendix (right), sigmoid (left), ureter and external iliac vessels (extraperitoneal)

Posterolateral

Kidney and adrenal (extraperitoneal)

Transverse

Right upper quadrant

Gallbladder, infant pylorus, colostomy

Mid-abdominal

Small-bowel, colon, kidney, lumbar sympathetic chain, vena cava (right)

Lanz

Caecum–appendix (right)

Pfannenstiel

Ovary/tube/uterus, prostate (extraperitoneal)

Thoraco-abdominal

Right

Liver and portal vein

Left

Gastro-oesophageal junction, enormous spleen

Assess

Right lobe of liver, gallbladder, left lobe of liver, spleen

Right lobe of liver, gallbladder, left lobe of liver, spleen

Diaphragmatic hiatus, abdominal oesophagus and stomach: cardia, body, lesser curve, antrum, pylorus and then duodenal bulb

Diaphragmatic hiatus, abdominal oesophagus and stomach: cardia, body, lesser curve, antrum, pylorus and then duodenal bulb

Bile ducts, right kidney, duodenal loop, head of pancreas; the transverse colon is drawn out of the wound towards the patient’s head

Bile ducts, right kidney, duodenal loop, head of pancreas; the transverse colon is drawn out of the wound towards the patient’s head

Body and tail of pancreas, left kidney

Body and tail of pancreas, left kidney

Root of mesentery, superior mesenteric and middle colic vessels, aorta, inferior mesenteric artery and vein, small-bowel and mesentery from ligament of Treitz to ileocaecal valve

Root of mesentery, superior mesenteric and middle colic vessels, aorta, inferior mesenteric artery and vein, small-bowel and mesentery from ligament of Treitz to ileocaecal valve

Appendix, caecum, colon, rectum

Appendix, caecum, colon, rectum

Pelvic peritoneum, uterus, tubes and ovaries in the female, bladder

Pelvic peritoneum, uterus, tubes and ovaries in the female, bladder

Hernial orifices and main iliac vessels on each side: the ureters can sometimes be seen in thin patients, or if they are dilated.

Hernial orifices and main iliac vessels on each side: the ureters can sometimes be seen in thin patients, or if they are dilated.

Action

Crushing clamps are applied to seal the bowel when it is cut. Payr’s powerful double-action clamps are most frequently used, but Lang Stevenson devised a similar clamp with narrow blades. Cope’s triple clamps allow the middle clamp to be removed, so that the bowel can be divided through the crushed area, leaving its ends sealed. These clamps are useful in partial gastrectomy.

Crushing clamps are applied to seal the bowel when it is cut. Payr’s powerful double-action clamps are most frequently used, but Lang Stevenson devised a similar clamp with narrow blades. Cope’s triple clamps allow the middle clamp to be removed, so that the bowel can be divided through the crushed area, leaving its ends sealed. These clamps are useful in partial gastrectomy.

Non-crushing clamps have longitudinal ridges and control the leakage of bowel contents without causing irreversible damage to the gut. Lane’s twin clamps, which can be locked together, allow two segments of intestine to be occluded and held in apposition for anastomosis. Pringle’s clamps hold cut ends of bowel securely, and the lightly crushed segment is so narrow that it can safely be incorporated in the anastomosis.

Non-crushing clamps have longitudinal ridges and control the leakage of bowel contents without causing irreversible damage to the gut. Lane’s twin clamps, which can be locked together, allow two segments of intestine to be occluded and held in apposition for anastomosis. Pringle’s clamps hold cut ends of bowel securely, and the lightly crushed segment is so narrow that it can safely be incorporated in the anastomosis.