Laparoscopic Nissen Fundoplication

Elizabeth A. Warner

Brant K. Oelschlager

DEFINITION

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), as defined by the Montreal Consensus Group in 2006, is caused by gastric reflux, causing troublesome symptoms and/or complications to the patient that adversely affect their well-being.1 Symptoms can include heartburn, acid brash, regurgitation, dysphagia, noncardiac chest pain, and pulmonary symptoms such as cough and hoarseness. Complications include esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, esophageal stricture, and aspiration pneumonia.

GERD results from incompetency or dysfunction of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). Important factors for adequate LES function include esophageal contraction, gastric cardia sling fibers, diaphragmatic crus, and intraabdominal position of the LES complex. Hiatal hernias efface the natural valve anatomy, allowing the GE junction to be displaced into the chest, exposing the LES to negative intrathoracic pressure and increased gastroesophageal reflux. A certain amount of gastroesophageal reflux is physiologic and not pathologic. However, once symptoms become troublesome to the patient, a diagnosis of GERD can be made.

GERD can also be due to inadequate esophageal motility resulting in poor clearance of physiologic reflux. Similarly, delayed gastric emptying can lead to GERD due to the increased volume and duration of gastric contents that can potentially reflux into the esophagus.

A fundoplication is the use of the gastric fundus to recreate the LES valve function. Various fundoplication configurations exist (e.g., Nissen, Dor, Toupet) and differ by the number of degrees that encircle the esophagus, the location of the wrap, and the approach used to create the fundoplication.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Peptic ulcer disease

Esophageal motility disorder (e.g., achalasia)

Malignancy (e.g., esophageal or gastric) Anatomic abnormality (e.g., hiatal hernia)

Eosinophilic esophagitis

Coronary artery disease

Biliary colic

Pancreatitis

Functional heartburn

Hypersensitive esophagus

Functional dyspepsia

Other functional bowel diseases (i.e., inflammatory bowel syndrome [IBS])

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The most common gastroesophageal reflux symptoms reported are heartburn, acid regurgitation, and dysphagia. There is a growing awareness of more atypical presentations, most of which are related to laryngeal or pulmonary manifestations such as cough, chest pain, hoarseness, wheezing, globus sensation, and aspiration.2

It is important to ask the patient to explain the sensations they are having when they use the term “heartburn.” Heartburn, as related to GERD, is a retrosternal burning or caustic sensation. Some patients incorrectly use the term heartburn to describe epigastric pain (associated with peptic ulcer disease, gastritis, and functional dyspepsia), right upper quadrant pain (from cholelithiasis or other hepatobiliary diseases), or chest pain (from coronary artery disease). It is helpful to ask patients to point on their body as to where they have discomfort when they note that they have heartburn. Classic heartburn does not radiate to the back nor is it usually described as a pressure sensation.

Regurgitation symptoms can include gastric fluid regurgitation, known as water brash, and/or partially digested food. Regurgitation of food particles can also be associated with esophageal clearance problems such as an esophageal diverticulum or achalasia.

Dysphagia from a reflux-associated stricture is usually worse with solids than liquids. If both are equally bothersome, a neuromuscular disorder must also be considered.

Airway-related symptoms (e.g., cough, wheezing, voice changes) can be present alone or in conjunction with esophageal symptoms.

Disease states that are sometimes related to GERD are idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, asthma, and recurrent pneumonia.

Patients presenting to a surgeon to discuss GERD treatment have often already trialed antacid medications. It is important to query the patient’s response to these medications. If the patient does not have at least symptomatic improvement to antacid therapy, alternative diagnoses should be considered. Heartburn will almost always improve with antacid therapy, at least partially, within days to a few weeks. Similarly, they will notice worsening of heartburn symptoms with cessation of antacid therapy. Airway symptoms may take longer (2 to 3 months) and may not respond at all (even when GERD is the etiology).

Physical examination findings are often limited in a patient with GERD. In all patients with gastroesophageal complaints, it is important to query about weight loss and hematemesis and to examine for lymphadenopathy, as these could represent an underlying malignancy.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Diagnostic testing to confirm objective evidence of abnormal gastroesophageal reflux is imperative before considering surgical management for GERD. A recent study revealed that 42% of patients referred for antireflux surgery had a normal pH study when tested objectively.3 The following studies are

essential to confirm the diagnosis of GERD, the underlying functionality of the LES and esophagus, and investigate any anatomic considerations necessary for successful operative outcomes:

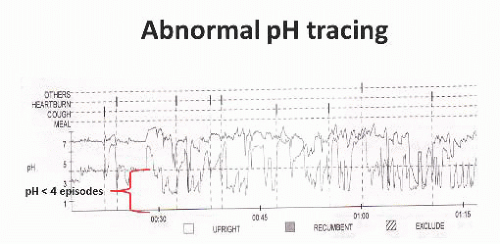

FIG 1 • Sample of 24-hour pH tracing demonstrating significant acid reflux with good symptom correlation.

pH monitoring (FIG 1) assesses distal esophageal pH over a period of time (routinely 24 to 48 hours) and a composite DeMeester score is calculated. An abnormal DeMeester score is greater than 14.7.4 Factors contributing to this score include percent total time pH less than 4, percent upright time pH less than 4, percent supine time pH less than 4, number of reflux episodes, number of reflux episodes more than 5 minutes, and longest reflux episode.

Upper endoscopy evaluates for esophageal injury and Barrett’s esophagus secondary to GERD while excluding malignant pathology with biopsies as necessary. Endoscopy allows the surgeon to evaluate for the presence of a hiatal hernia as well as to visually inspect the LES.

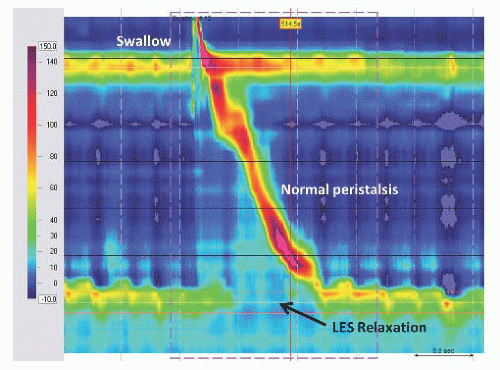

Esophageal manometry (FIG 2) assesses LES pressure and relaxation as well as esophageal motility. Patients with esophageal motility disorders can easily be mislabeled as having GERD based on symptoms. Understanding a patient’s esophageal motility is necessary to plan successful antireflux surgery.

Esophagogram evaluates gastroesophageal anatomy and abnormalities such as hernia, stricture, diverticula, motility, or tumors.

Ancillary tests that may also be useful include laryngoscopy, gastric emptying scintigraphy, and impedance testing.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

There is rarely an absolute indication for antireflux surgery in a patient with GERD. Medical management, including acid suppression therapy and lifestyle modifications (e.g., dietary changes, weight loss), is usually sufficient to manage most patients’ GERD symptoms. Many factors must be considered in making the decision to proceed with antireflux surgery. These include symptom severity, symptom control with medical therapy, complications of GERD (e.g., severe esophagitis, esophageal stricture, Barrett’s esophagus, chronic respiratory complaints), and the generalized health of the patient.

Patients best suited for an antireflux procedure are those with documented and confirmed GERD for whom medical and lifestyle changes are not providing adequate quality-of-life improvement. When the quality-of-life impairment justifies accepting the risk of surgery, antireflux surgery is indicated.

Preoperative Planning

Positioning

Patient can be positioned in either modified lithotomy position or supine depending on surgeon preference. Lithotomy position requires more time and equipment and has more risks of nerve injury. However, lithotomy position provides superior ergonomics for the surgeon. Both arms should be tucked to not interfere with instrumentation and the patient should be adequately stabilized on the bed to safely accommodate steep reverse Trendelenburg (which allows organs to naturally fall away from the hiatus and left upper quadrant).

Standard trocar placement includes three working trocars, a fourth trocar for the camera, and a fifth for liver retraction. FIG 3 illustrates standard trocar placement, surgeon, and assistant positioning.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree