■ Hernias are frequently diagnosed on computed tomography (CT) for abdominal pain, although this is not the initial test to obtain if you are most suspicious of hiatal hernia. It will, however, usually make the diagnosis and can rule in or out other things.

■ Upper endoscopy can be helpful for visualizing the size of the hernia and more for examining the mucosa for associated conditions.

■ Cameron’s erosions are linear erosions that can be found in the stomach related to constriction by the diaphragm.

■ Changes related to associated GERD can also be seen in the esophagus such as erosive esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus.

■ Any neoplastic lesion should be ruled out prior to operative repair.

■ Manometry is valuable in planning the antireflux procedure that will be performed in conjunction with repair of the hernia. Normal motility will allow for creation of a full wrap, as opposed to partial.

■ pH testing is not generally required, unless the patient is presenting primarily with GERD symptoms. In this case, it may be useful as a baseline.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

■ Indications for repair of hiatal hernias:

■ Sliding hiatal hernias (type I) should not be repaired unless the indication is associated GERD, in which case, they should be repaired at the time of planned fundoplication.

■ PEHs (types II to IV) should generally be repaired if symptomatic. In younger (<60 years of age) and healthier patients, repair of even relatively asymptomatic hernias is indicated given the risk of incarceration, although this risk is smaller than once thought.

■ Mesh hiatal hernia repairs generally need to be considered only in patients with PEHs (larger hernias).

■ Many patients with hiatal hernias are elderly, and they may have serious comorbidities or frailty. In these patients, a thorough medical evaluation should be completed prior to any elective hernia repair.

■ Some of them may be too frail or high risk for a full hiatal hernia repair with fundoplication but are very symptomatic and need intervention. In these patients, it may be more prudent to plan for a shorter procedure without full dissection of the hernia sac; hernia reduction with gastrostomy tube gastropexy may be more appropriate in these patients.

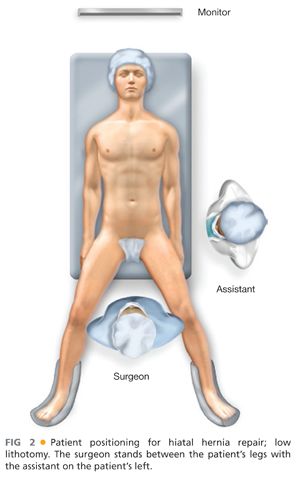

Positioning

■ As for other foregut procedures, patients should be in low lithotomy with a beanbag support and both arms tucked (FIG 2).

■ The patient will be in steep reverse Trendelenburg for most of the case.

■ The surgeon can operate from the foot of the table, with the assistant on the patient’s left.

TECHNIQUES

SETUP AND PORT PLACEMENT

■ After sterile prep, the upper abdomen is draped. Equipment for laparoscopy is passed off and secured.

■ The peritoneal cavity is accessed using a Veress needle, and pneumoperitoneum is obtained.

■ An 11-mm cutting optical trocar is inserted in the left subcostal position.

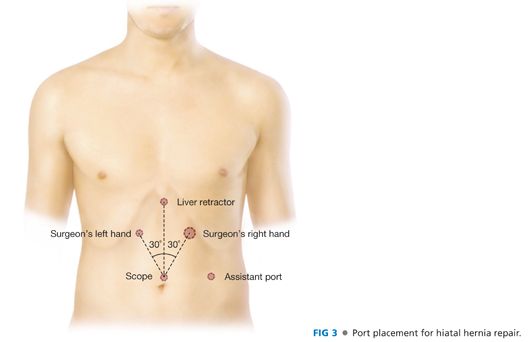

■ Additional ports are placed under direct vision as follows (FIG 3):

■ Camera port (11 mm) in epigastric position; a 5-mm port can also be placed here depending on surgeon preference for scope size.

■ Assistant (5 mm) port in left lateral position

■ Surgeon’s left hand port (5 mm) in right upper quadrant

■ A Nathanson liver retractor is then placed in the upper midline for retraction of the left lobe.

REDUCTION

■ The stomach and any other hernia contents are reduced into the abdominal cavity as possible; with a PEH, the stomach will almost never fully reduce and the surgeon should not attempt to do so. Just reduce the stomach that is free and not attached within the mediastinum.

MOBILIZATION

■ The short gastric vessels are ligated with an electrical or ultrasonic sealing device in order to mobilize the fundus fully. Begin ligation near the inferior border of the spleen (see FIG 3).

■ Care must be taken to also divide any attachments or vessels between the fundus and the retroperitoneum as adhesions are common.

DISSECTION OF HIATUS AND HERNIA SAC

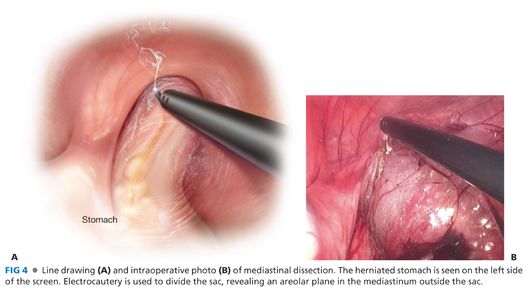

■ The phrenoesophageal membrane and hernia sac are divided at the muscular edge of the crus.

■ Once the crus is visualized, the surgeon can be assured that all layers of the sac have been divided. In this way, the surgeon begins to develop a plane outside of the hernia sac and not within it.

■ The attachment of the sac to the hiatus is divided until it is freed circumferentially. After this is complete, the sac is released from the mediastinum, with care to avoid the pleura (FIGS 4 and 5). This is facilitated with the use of gentle traction and the diffusion of carbon dioxide (CO2) from the pneumoperitoneum.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree