Laparoscopic Mesh Hiatal Hernia Repair

Ellen H. Morrow

Brant K. Oelschlager

DEFINITION

A hiatal hernia is an enlarged diaphragmatic hiatus, allowing for passage of the stomach or other organs into the chest.

Hiatal hernia is traditionally divided into several types; the principle difference is sliding versus paraesophageal. The sliding type is much more common. This is type I.

Paraesophageal is type II. This involves herniation of the stomach above the gastroesophageal (GE) junction, which remains in the abdomen.

Type III is a combination of types I and II, with the GE junction in the chest, but with stomach herniating above it. This is also referred to as a paraesophageal hernia (PEH) and is much more common than a type II.

A type IV PEH involves herniation of additional organs other than stomach such as the transverse colon.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The type of hiatal hernia should be discerned as described under definition and differentiated from other nonhiatal diaphragmatic hernias.

This is a diagnosis that is often made with imaging prior to surgical referral. If imaging has not yet been performed, there are other entities that could have similar clinical presentation.

These include gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, chronic mesenteric ischemia, angina, myocardial infarction, or aortic dissection.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Like type I hernias, these patients may present with GERD symptoms (e.g., heartburn, regurgitation, symptoms related to aspiration, etc.); however, at least half of patients will not complain of significant GERD. Patients will often present with a history of postprandial abdominal or chest pain, early satiety, dysphagia, and regurgitation. Symptoms are frequently related to the volume of food they have consumed. They may have associated weight loss.

PEHs can also present with respiratory symptoms such as dyspnea or cough. Anemia is a common presenting symptom of a large hiatal hernia and is often the only finding in a gastrointestinal (GI) workup.

Rarely, PEHs can present with acute obstruction.

This is often caused by gastric volvulus.

This will present with increased severity of symptoms; complete intolerance to oral intake; severe pain; and occasionally, even systemic inflammatory response or sepsis if the stomach becomes ischemic.

There are not generally physical findings specific to this condition.

The patient can be examined for changes associated with GERD in the oropharynx.

Abdominal exam may reveal some epigastric tenderness.

There may be signs of weight loss or overall frailty.

There may be diminished breath sounds.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

The workup for hiatal hernia is similar to the GERD workup.

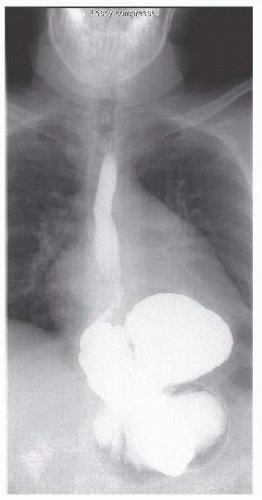

An esophagram is often the most valuable study; this provides images of the hernia in a dynamic fashion using fluoroscopy (FIG 1). This is the best study for getting an overall size and position of the stomach within the hernia.

Hernias are frequently diagnosed on computed tomography (CT) for abdominal pain, although this is not the initial test to obtain if you are most suspicious of hiatal hernia. It will, however, usually make the diagnosis and can rule in or out other things.

Upper endoscopy can be helpful for visualizing the size of the hernia and more for examining the mucosa for associated conditions.

Cameron’s erosions are linear erosions that can be found in the stomach related to constriction by the diaphragm.

Changes related to associated GERD can also be seen in the esophagus such as erosive esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus.

Any neoplastic lesion should be ruled out prior to operative repair.

Manometry is valuable in planning the antireflux procedure that will be performed in conjunction with repair of the hernia. Normal motility will allow for creation of a full wrap, as opposed to partial.

pH testing is not generally required, unless the patient is presenting primarily with GERD symptoms. In this case, it may be useful as a baseline.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

Indications for repair of hiatal hernias:

Sliding hiatal hernias (type I) should not be repaired unless the indication is associated GERD, in which case, they should be repaired at the time of planned fundoplication.

PEHs (types II to IV) should generally be repaired if symptomatic. In younger (<60 years of age) and healthier patients, repair of even relatively asymptomatic hernias is indicated given the risk of incarceration, although this risk is smaller than once thought.

Mesh hiatal hernia repairs generally need to be considered only in patients with PEHs (larger hernias).

Many patients with hiatal hernias are elderly, and they may have serious comorbidities or frailty. In these patients, a thorough medical evaluation should be completed prior to any elective hernia repair.

Some of them may be too frail or high risk for a full hiatal hernia repair with fundoplication but are very symptomatic and need intervention. In these patients, it may be more prudent to plan for a shorter procedure without full dissection of the hernia sac; hernia reduction with gastrostomy tube gastropexy may be more appropriate in these patients.

Positioning

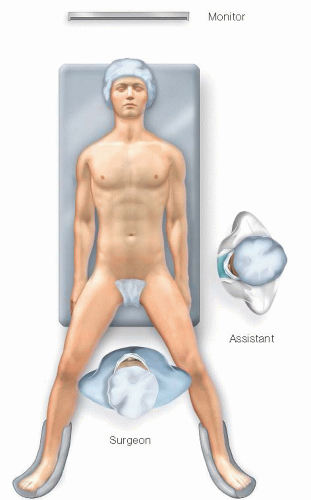

As for other foregut procedures, patients should be in low lithotomy with a beanbag support and both arms tucked (FIG 2).

The patient will be in steep reverse Trendelenburg for most of the case.

The surgeon can operate from the foot of the table, with the assistant on the patient’s left.

FIG 2 • Patient positioning for hiatal hernia repair; low lithotomy. The surgeon stands between the patient’s legs with the assistant on the patient’s left. |

TECHNIQUES

SETUP AND PORT PLACEMENT

After sterile prep, the upper abdomen is draped. Equipment for laparoscopy is passed off and secured.

The peritoneal cavity is accessed using a Veress needle, and pneumoperitoneum is obtained.

An 11-mm cutting optical trocar is inserted in the left subcostal position.

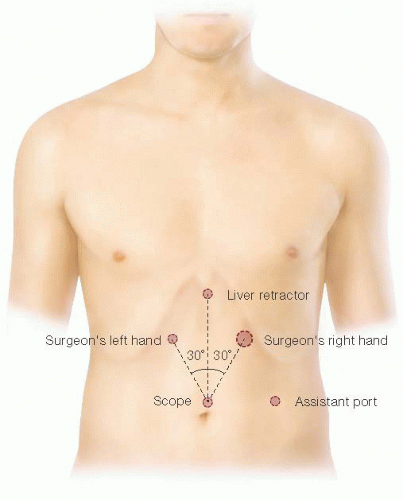

Additional ports are placed under direct vision as follows (FIG 3):

Camera port (11 mm) in epigastric position; a 5-mm port can also be placed here depending on surgeon preference for scope size.

Assistant (5 mm) port in left lateral position

Surgeon’s left hand port (5 mm) in right upper quadrant

A Nathanson liver retractor is then placed in the upper midline for retraction of the left lobe.

FIG 3 • Port placement for hiatal hernia repair.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|