Laparoscopic Biliopancreatic Diversion with Duodenal Switch

Alfons Pomp

Gregory Dakin

Introduction

Bariatric surgery is considered the most effective treatment for morbid obesity. Most of the operations currently performed, such as gastric bypass, adjustable gastric banding, or the relatively new sleeve gastrectomy, utilize caloric restriction as the primary means to achieve weight loss. However, long-term data has shown that for many patients, particularly those that start with a BMI > 50 kg/m2, such restrictive operations have a high rate of failure, with regard to both, percentage of excess weight loss (% EWL) achieved and to subsequent weight regain. The biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD-DS) is an operation that combines a restrictive component (sleeve gastrectomy) with a significant malabsorptive intestinal rearrangement. Literature demonstrates that the BPD-DS (or its predecessor BPD) is the most effective weight loss operation, inducing the greatest weight loss and resolution of comorbidities such as diabetes. This has been shown to be durable out to 15 years follow-up.

Table 1 Bariatric Procedures Performed Worldwide | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Despite the success of the operation, the BPD-DS constitutes only 5% of procedures performed (see Table 1). This is likely due to several reasons, including the perceived high rate of metabolic complications such as protein-calorie malnutrition, vitamin and mineral deficiencies, and the technical difficulty of the procedure when compared to other more common operations. While there is no doubt that it is the most technically demanding of bariatric procedures, with proper patient selection and careful follow-up, the BPD-DS can be performed safely with a long-term complication profile similar to that of

gastric bypass. It is a particularly good option for the super-obese patient and for those patients who have failed other operations, and should be a weapon in every bariatric surgeon’s armamentarium.

gastric bypass. It is a particularly good option for the super-obese patient and for those patients who have failed other operations, and should be a weapon in every bariatric surgeon’s armamentarium.

History of the Procedure

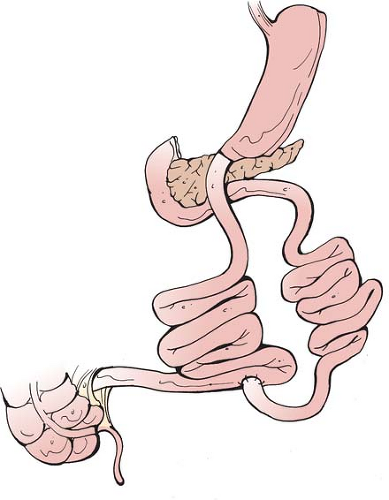

Malabsorptive operations for morbid obesity date back to the 1950s, when the first reports of the jejunal-ileal bypass (JIB) were published. The most widely accepted version of the operation used a 35-cm segment of proximal jejunum anastomosed to the distal 10 cm of terminal ileum (see Fig. 1). Although this operation was successful in inducing weight loss, there were high rates of significant long-term complications, including bacterial overgrowth, vitamin deficiency, renal failure, and ultimately hepatic failure. These problems led to the development of other bariatric procedures, notably the gastric bypass by Edward Mason, in the 1960s, and the JIB was largely abandoned.

Nicola Scopinaro is credited with the first description of the biliopancreatic diversion (BPD) for morbid obesity when he published his first human series of 18 patients followed for a year. His procedure was developed to maintain the malabsorptive component of the JIB while eliminating the long blind limb believed to contribute to many of the long-term problems. He performed a distal gastrectomy and anastomosed a 250-cm distal Roux limb to the proximal stomach, with the long biliopancreatic limb anastomosed to this limb 50 cm from the ileocecal valve to create a short common channel. Weight loss with the BPD is excellent and sustainable out to 15 years.

In 1993, Marceau described the first duodenal switch operation for morbid obesity. He modified Scopinaro’s BPD by creating a vertical (or sleeve) gastrectomy rather than a distal gastrectomy and then anastomosed the Roux limb to the stapled (nondivided) proximal duodenum. While this minimized problems with dumping and marginal ulcers seen with the BPD, staple-line breakdown in the duodenum led to later weight regain. The Marceau duodenal switch was further modified by Hess and Hess in 1998 with the division of the duodenum, leading to the modern-day BPD-DS.

The current BPD-DS consists of a sleeve gastrectomy with an alimentary limb of approximately 150 to 200 cm anastomosed to the proximal duodenum, and a 50 to 100 cm common channel (see Fig. 2). The operation can be performed laparoscopically, first described by Gagner in 2000.

Perhaps more so than any other bariatric operation, patient selection for the BPD-DS is of utmost importance. Owing to its malabsorptive component, the BPD-DS can result in significant malnutrition if a patient is not meticulous about their dietary behavior as well as surgical follow-up. We often invoke a rule of thumb that a patient should be at “the head of their class” for consideration of BPD-DS. While there is no specific weight criterion, we favor the BPD-DS in patients with a BMI > 50 kg/m2, provided the patient can demonstrate appropriate understanding of the nutritional demands of the operation as well as ability to follow-up appropriately. For those patients with a BMI > 60 kg/m2, we favor a staged approach in which the patient first undergoes laparoscopic sleeve

gastrectomy and after significant weight loss over a period of 12 to 18 months returns to the operating room for a second-stage duodenal switch.

gastrectomy and after significant weight loss over a period of 12 to 18 months returns to the operating room for a second-stage duodenal switch.

All patients undergo an intensive multidisciplinary evaluation. The initial office visit includes a detailed history and physical exam, with particular attention to previous dietary efforts, medical comorbidities, surgical history, and previous thromboembolic event. Patients considered at high risk for deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolisms, such as those with a prior event or extreme BMI, are referred for evaluation of preoperative vena caval filter placement. While there are several predictors of poor outcomes from bariatric surgery, we generally do not offer surgery to nonambulatory patients. Additional components of the standard evaluation include psychology/psychiatry to ensure understanding of the procedure, appropriate rational for undergoing surgery, and absence of any untreated eating disorder. A thorough gastroenterologic evaluation is performed including upper endoscopy and biopsy for Helicobacter pylori, which is eradicated if present. Additional medical evaluation (cardiac, pulmonary, and endocrine) are obtained as necessary.

All patients undergo intensive nutritional counseling with specialized bariatric nutritionists experienced in managing patients after BPD-DS. It is critical that the nutritionists be closely involved with the bariatric practice such that communication between surgeon and nutritionist is facile. All patients demonstrate knowledge of the procedure by completing a questionnaire detailing the inherent risks and benefits of the operation. Finally, patients are extensively counseled that the BPD-DS, as with all bariatric procedures, is simply a tool to aid behavior modification, and is by no means a foolproof ticket to easy weight loss.

Laparoscopic Bpd-Ds Operative Technique

Before undertaking the operation, we feel that it is essential to have a dedicated operating room team that is adept with advanced laparoscopic bariatric procedures and the BPD-DS in particular. The operation is complex and the value of a team of anesthesiologists and nurses familiar with the set-up and instrumentation cannot be stressed enough.

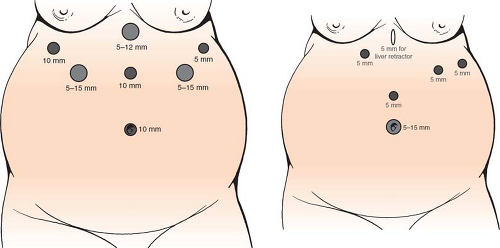

After induction of general anesthesia, a urinary catheter is placed, DVT prophylaxis is given (compression stockings and subcutaneous heparin injection), and appropriate broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage administered. It is our preference to position patients in the supine, split-leg position for all bariatric operations. We use a standard open entry technique into the abdomen at the umbilicus to establish pneumoperitoneum. We conduct a visual inspection of the abdomen, looking at the size of the liver and of the abdominal domain, as well as any necessary lysis of adhesions before proceeding with trocar placement to ensure that we will be able to complete the full operation. If there are anatomic concerns due to extreme body habitus, large liver or bulky omentum that will create an unfavorable operating environment, we will opt to perform only the sleeve gastrectomy as a “first-stage” procedure. When performing only sleeve gastrectomy, our trocar arrangement and bougie are different than when doing the entire BPD-DS (see Fig. 3).

Once the trocars are placed, we proceed with the sleeve gastrectomy by first dividing the gastrocolic omentum off the greater curvature of the stomach with the ultrasonic scalpel. This dissection is carried from the proximal 2 cm of duodenum all the way up to the Angle of His. Any posterior attachments to the stomach are divided such that the stomach is freely mobile, thereby facilitating its manipulation into the staplers during transection. As well, it is essential that the entire posterior fundus be released off the left crus of the diaphragm to ensure the sleeve be of uniform size.

The stomach transection begins on the greater curvature at the level of the crow’s foot just distal to an imaginary vertical line created from the incisura (Fig. 4). We utilize 60-mm length staplers for the entire resection. The staple-firings for the thick antral tissue should be 4.5 mm in height (usually the first two to three firings) and thereafter can change to 3.5-mm height. We typically use one of several commercially available reinforcing strips to buttress the staple line and reduce bleeding

(note however, that we omit this buttress on the first firing as that portion of the antrum is typically too thick to allow proper staple closure with the addition of the buttress). After the first two firings, a 40 to 50 F bougie is placed and guided toward the pylorus to aid in the resection. The bougie should be held in place the entire time by the anesthesiologist to avoid accidental movement and/or transection of the bougie. The right upper quadrant, umbilical, and left upper quadrant trocars can all be used for the transection. The staple line is inspected for hemostasis and proper staple closure. Any bleeding points are oversewn with 2-0 Vicryl suture. The stomach specimen is removed using an endobag via the umbilical port (note: if the stomach is placed in the bag such that the corner of the first staple line is left outside, that corner can be easily grasped once the bag is delivered through the wound. This will orient the stomach longitudinally and it can then be extracted with only minimal dilation of the trocar site.)

(note however, that we omit this buttress on the first firing as that portion of the antrum is typically too thick to allow proper staple closure with the addition of the buttress). After the first two firings, a 40 to 50 F bougie is placed and guided toward the pylorus to aid in the resection. The bougie should be held in place the entire time by the anesthesiologist to avoid accidental movement and/or transection of the bougie. The right upper quadrant, umbilical, and left upper quadrant trocars can all be used for the transection. The staple line is inspected for hemostasis and proper staple closure. Any bleeding points are oversewn with 2-0 Vicryl suture. The stomach specimen is removed using an endobag via the umbilical port (note: if the stomach is placed in the bag such that the corner of the first staple line is left outside, that corner can be easily grasped once the bag is delivered through the wound. This will orient the stomach longitudinally and it can then be extracted with only minimal dilation of the trocar site.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree