Laparoscopic Antireflux Surgery

Nathaniel J. Soper

Eric S. Hungness

Introduction

Laparoscopic antireflux surgery continues to play a major role in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). The development of minimally invasive surgical techniques for the treatment of GERD lowered the threshold for surgical treatment of this disease and renewed interest in the pathophysiologic features and treatment outcomes. Most operations for GERD involve plicating the gastric fundus 90 to 360 degrees around the distal esophagus. The most commonly performed fundoplication is the Nissen 360-degree fundoplication, which results in >90% long-term control of reflux symptoms. Other fundoplications (e.g., Hill, Belsey, Toupet, Dor, Guarner, Lind) have been developed, applied, and reported, but modifications of the Nissen fundoplication currently are the most widely used operations for GERD.

A randomized trial comparing transabdominal open Nissen fundoplication with medical therapy in patients with complicated GERD proved surgical therapy to be more effective. Despite these findings, many patients and physicians opted instead for lifelong medication and significant lifestyle limitations until 1991, when Dallemagne and Geagea reported the first laparoscopic Nissen fundoplications (LNF). Although LNF follows the same surgical principles as the open operation, randomized trials showed that the laparoscopic approach reduces postoperative pain and shortens both hospitalization and recuperation with outcomes (symptomatic and functional) similar to that of the open operation. Hence, there was a rapid increase in surgical treatment of GERD, with LNF gaining acceptance as an efficacious therapy for GERD.

Over the past decade, however, the number of antireflux operations being performed has decreased as “better” medications have been developed, resulting in increased resistance from the medical community to refer patients for surgical evaluation. Recent reports and FDA warnings of potential complications with long-term PPI use, however, has caused increased discussion in the medical community of the role of surgery in the treatment of GERD.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

Demographics and Clinical Presentation

An estimated 61 million Americans complain of heartburn and indigestion, with approximately 40% of the total US population experiencing reflux on a monthly basis, 20% on a weekly basis, and 7% on a daily basis. Patients with GERD may exhibit typical or atypical symptoms (Table 1). GERD usually presents as heartburn and regurgitation and can progress to dysphagia, odynophagia, and chest pain. Although typical of GERD, these symptoms may also be caused by other entities that must be included in the differential diagnosis, including cardiopulmonary disease, other foregut problems, gallbladder disease, and functional disturbances.

Table 1 Symptoms of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Anatomy

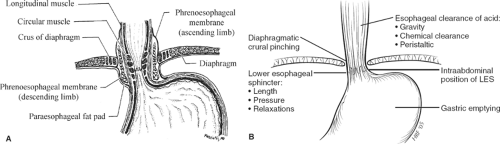

Barriers to gastroesophageal reflux (GER) include the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), the presence of an intra-abdominal segment of esophagus, the diaphragmatic crura, the phrenoesophageal membrane, the angle of His, and esophageal clearance of acid. The LES and hiatal crura appear to be the major barriers (Fig. 1A, B). The LES separates two adjacent lower-pressure zones and normally remains tonically contracted except during swallowing, when it relaxes in advance of the peristaltic wave. LES contraction receives important amplification during inspiration and conditions in which the abdominal pressure is increased by contraction of the crural diaphragm. Reflux events in healthy individuals normally result from the phenomenon known as transient relaxation of the LES complex, in which spontaneous (non-swallow initiated) events permit GER by obliterating the high-pressure zone through a vagally mediated mechanism that is usually stimulated by gastric or pharyngeal stimulation.

Pathophysiology

GER occurs physiologically in all healthy individuals to a limited degree. Patients with GERD experience reflux more frequently and for longer periods of time than healthy persons. Reflux events may occur by three primary mechanisms: (i) spontaneously, accompanying transient LES relaxations; (ii) stress reflux associated with a weakened LES, the pressure of which does not exceed that of the elevated intra-abdominal pressure; and (iii) in individuals with severe reflux, essentially a nonexistent LES that cannot maintain competency at any point, resulting in spontaneous GER. Patients with long-standing and/or severe GERD may ultimately develop Barrett esophagus, columns of metaplastic esophageal mucosa associated with an increased risk of adenocarcinoma.

Some authors have proposed that transient LES relaxations lead to initial damage to the esophageal mucosa. This is exacerbated by stress reflux usually caused by gastric distention, most commonly from overeating. The progressive mucosal inflammation leads to LES dysfunction, which leads to further reflux. This vicious cycle eventually leads to an incompetent LES. These events may also lead to esophageal dysmotility that may prevent normal esophageal clearance of acid.

Savary et al. established a grading system for the endoscopic appearance of reflux-induced damage to the esophageal mucosa as follows: grade I (mild erythema), grade II (isolated ulcerations), grade III (confluent severe ulcerations), and grade IV (secondary complications including Barrett esophagus and stricture). The Los Angeles Classification System, the most commonly used system by gastroenterologists, grades esophagitis according to breaks in the esophageal mucosa: grade A (≤5 mm in length), grade B (>5 mm in length), grade C (continuous between two mucosal folds), and grade D (≥75% of esophageal circumference). However, up to 60% of patients with clinical GERD will have normal-appearing esophageal mucosa at endoscopy. Barrett esophagus is estimated to occur in approximately 10% of patients with GERD. Studies demonstrate that patients with GERD and Barrett esophagus have an estimated 0.4% per patient-year risk of developing adenocarcinoma, compared with a 0.07% per patient-year risk for patients with GERD but without Barrett esophagus.

Diagnosis

Factors other than mechanical barrier deficits at the LES may lead to GERD, and GERD-like symptoms can be reported in the absence of GERD. The esophageal body plays an important role in clearing acid present within its lumen, a function that is aided by the presence of gravity and saliva. Esophageal peristaltic dysfunction is directly related to the degree of mucosal disease, and most patients with Barrett esophagus exhibit abnormalities of esophageal motor function. Abnormalities of the gastric reservoir, including gastric dilatation and delayed gastric emptying, may also predispose to GER. Antireflux operations are designed solely to correct a functionally defective reflux barrier; therefore, tests that measure the function not only of the LES itself but also of the esophagus and stomach may be appropriate in patients with GERD-related symptoms.

Preoperative Testing

Many diagnostic modalities are available for studying patients suspected of having GERD (Table 2). A history of recurrent heartburn alone is usually adequate to establish the

clinical diagnosis of GERD and initiate empiric medical therapy. However, investigations should be performed in those patients with persistent symptoms, symptoms and signs indicating significant tissue injury (e.g., dysphagia, anemia, or guaiac positive stools), and any patient in whom the diagnosis is uncertain. Individuals who are being considered for antireflux surgery require additional tests of the anatomic and physiologic features of the stomach and esophagus.

clinical diagnosis of GERD and initiate empiric medical therapy. However, investigations should be performed in those patients with persistent symptoms, symptoms and signs indicating significant tissue injury (e.g., dysphagia, anemia, or guaiac positive stools), and any patient in whom the diagnosis is uncertain. Individuals who are being considered for antireflux surgery require additional tests of the anatomic and physiologic features of the stomach and esophagus.

Table 2 Diagnostic Tests for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease | ||

|---|---|---|

|

In patients with typical symptoms of GERD, the minimal diagnostic evaluation is esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). Esophageal manometry should be performed preoperatively to assess the adequacy of esophageal peristalsis. High-resolution manometry is now available and offers a more detailed look at esophageal anatomy and function. Twenty-four-hour pH testing may be helpful, but is not mandatory in patients with typical symptoms if esophagitis is present. However, patients without esophagitis and those who have atypical symptoms of GERD or other functional gut disorders, such as irritable bowel syndrome, and those patients with an atypical response to medical therapy require more detailed preoperative investigation, generally including a pH test to prove the presence of GERD.

Anatomic Delineation

EGD is an essential part of the evaluation of patients being considered for antireflux surgery. Barrett esophagus usually appears as salmon-colored mucosal extensions up into the distal esophagus and is confirmed by biopsy that shows intestinal metaplasia. Given the increasing incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma and the association between long-standing heartburn and adenocarcinoma, the gastroesophageal mucosa should probably be assessed endoscopically at least once in all patients with persistent or severe symptoms of GERD. If Barrett esophagus with severe dysplasia is discovered on biopsy, the patient should be considered for esophageal resection rather than antireflux surgery because up to 50% of these patients will harbor unsuspected adenocarcinoma.

Contrast radiographs of the upper gastrointestinal tract may be helpful in assessing the size of any associated hiatal hernia, to localize precisely the gastroesophageal junction in relation to the esophageal hiatus, and to qualitatively assess the adequacy of esophageal peristalsis and gastric emptying.

Physiologic Examinations

The “gold standard” to confirm the presence of GER is a 24-hour esophageal pH assessment, quantifying the number and duration of episodes of acid reflux into the esophagus. Furthermore, this test correlates subjective symptoms with reflux events and differentiates between upright and supine GER. The sensitivity of prolonged pH monitoring in identifying pathologic GER ranges from 50% to 100% (mean, 85%), and the specificity is somewhat higher. This test requires cessation of H2-blockers for 3 days and proton pump inhibitors for 7 days prior to testing. The recent development of an indwelling wireless esophageal probe has made this outpatient test more tolerable than when nasoesophageal probes were used; and although it is still relatively expensive, it also allows for capture of data up to 48 hours. False-negative tests may result from patients refraining from normal dietary and physical activities during the time the pH probe is in place.

Recently, intraluminal impedance monitoring has been added to the arsenal of diagnostic tests for GERD. Diagnosing GERD by pH monitoring alone depends on acid reflux, and may not detect low-acid or nonacid reflux. The precise role of impedance monitoring in the workup of patients with GERD still needs to be defined, but should be considered especially in patients with atypical and refractory symptoms.

Esophageal manometry, high resolution if possible, should be performed in all patients before antireflux surgery is considered. With this test, the length, location, and pressure of the LES are assessed along with the ability of the LES to relax during swallowing. Additionally, and more importantly, both the amplitude and efficacy of swallowing-induced peristalsis of the esophageal body is measured. Esophageal manometry identifies the rare individual with a primary motility abnormality (such as achalasia or scleroderma) with symptoms of GER. The degree of peristaltic failure caused by the GERD can also be assessed. The surgeon may, thereby, gauge whether a full 360-degree fundoplication will likely result in significant dysphagia, which may result in a tailoring of the antireflux operation. Furthermore, if dysphagia develops postoperatively, a baseline study is of value in determining subsequent treatment.

In patients whose symptoms include significant nausea and vomiting, and in those patients with severe insulin-dependent diabetes, a scintigraphic gastric emptying test should probably be performed to exclude a significant gastric-emptying abnormality. If a marked delay in gastric emptying is diagnosed, a pyloroplasty or pyloromyotomy should be considered at the time of antireflux surgery. Recent studies have demonstrated significant improvement in both symptoms and gastric emptying scintigraphy for reflux patients with severe gastroparesis (T½ >150 min) undergoing combined LNF and pyloroplasty.

Table 3 Lifestyle Modifications for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease | |

|---|---|

|

Treatment

Medical

Virtually, all patients should receive a short-term (2-month) trial of intensive medical therapy before considering an antireflux operation. Modern medical treatment of reflux disease is aimed at decreasing gastric acidity and reducing esophageal exposure to gastric contents with the goal of healing the injured esophageal mucosa, eliminating symptoms, and preventing or treating the complications of GERD. Most patients with GERD have relatively mild symptoms and may be managed empirically without further testing unless accompanied by signs indicative of significant tissue injury (e.g., dysphagia or gastrointestinal blood loss). The primary tenets of GERD management include lifestyle modifications (Table 3) and medical therapy. Unfortunately, recommendations for significant lifestyle modifications are usually ignored. Although most patients with GERD can be managed adequately with proton pump inhibitors, many eventually require escalating doses over time, relapse quickly when medication is stopped, or desire to be free of medications and their significant expense. It is this group of patients who may benefit greatly from LARS.

Endoluminal

Over the past 10 to 15 years, many commercially available endoluminal treatments for GERD have been developed by industry, all but one of which to date have failed either clinically or financially. The recent advent of natural orifice surgery and a better design has resulted in the development of the EsophyX device by endogastric solutions. This device uses permanent fasteners to create a “surgical” full-thickness partial fundoplication, as opposed to the previous mucosal approximating devices that failed. Patient selection is important as a hiatal hernia >2 cm or the presence of Barrett esophagus is a contraindication. Short-term results have been encouraging with over 80% of patients off PPIs at 1 year, despite only 40% normalization of pH; the treatment awaits validation by a multicenter randomized trial.

Surgical

Indications for Surgical Therapy

Conditions that require a surgical approach to GERD remain controversial. Foremost, the diagnosis of GERD must be clearly established. For a patient with typical symptoms (heartburn or regurgitation), at least one piece of objective evidence of reflux must be present. For patients with atypical symptoms, two pieces of corroborative evidence of GERD should be demonstrated. In addition to objective evidence of GERD, the most common indications for performing antireflux surgery can be summarized as follows: (a) complications of GERD not responding to medical therapy (e.g., esophagitis, stricture, recurrent aspiration or pneumonia, Barrett esophagus); (b) GERD symptoms interfering with lifestyle, despite medical therapy; (c) GERD associated with paraesophageal hernia; (d) chronic GERD requiring continuous drug therapy in a patient desiring discontinuation of medical therapy (e.g., financial burden, noncompliance, lifestyle choice, young age); and (e) intolerance to proton pump inhibitor therapy (Table 4).

Some features of preoperative physiologic testing predict a poor response to long-term acid suppression therapy and should be considered as rationale for referral to surgical therapy earlier in the course. These features include diminished contractility of the esophageal body, markedly hypotensive LES, severe erosive esophagitis that is poorly responsive to antacid therapy, and Barrett esophagus.

Whether the mere presence of Barrett esophagus should be an indication for antireflux surgery remains controversial. The development of Barrett esophagus generally occurs after long-term, severe GERD, and is therefore a marker for patients unlikely to respond to medical therapy. In addition, recent studies suggest that antireflux surgery results in regression of intestinal metaplasia in up to 35% of patients and regression of low-grade dysplasia in up to 75%. Likewise, surgery has been shown to reduce progression of intestinal metaplasia to dysplasia versus medical therapy. However, no prospective randomized trial has answered the question whether medical or surgical therapy prevents the progression of Barrett esophagus to adenocarcinoma. Two recent meta-analyses give conflicting results on this question. Based on these studies, we believe that patients with Barrett esophagus and severe symptoms of GERD should be offered surgical therapy. More data will be required before definitive recommendations can be made regarding the need for operative therapy in patients who have Barrett esophagus but few symptoms.

Recently, radiofrequency ablation has emerged as a potential therapy for the eradication of Barrett esophagus. Short-term results have been promising with up to 100% endoscopic and histological removal of Barrett esophagus and low-grade dysplasia. The use of this modality in conjunction with Nissen fundoplication has been described.

Contraindications to Surgical Therapy

Most, if not all, patients with GERD can be managed effectively for short periods of time with intensive medical therapy. A poor response to aggressive medical therapy may therefore portend a poor prognosis after antireflux surgery. There are few absolute contraindications to LARS. These include the inability to tolerate a general anesthetic or laparoscopy and an uncorrectable coagulopathy. Numerous conditions, however, render LARS more difficult and should be considered relative contraindications (Table 5). These factors include previous upper abdominal surgery, particularly operations around the diaphragm or esophageal hiatus, and severe obesity. In obese patients, access to the abdominal cavity is not generally a problem, but the omentum and gastrosplenic ligament may be bulky and difficult to retract adequately, and fatty infiltration of the left lateral segment of the liver may make exposure of the esophageal hiatus problematic. These patients should be considered for bariatric surgery, as this usually eliminates GERD. Chronic reflux can cause stricture and shortening of the esophagus and prevent the creation of a tension-free intra-abdominal gastric wrap, causing wrap disruption or intra-thoracic displacement. The propulsive force of the esophagus must also be sufficient to propel food across a reconstructed valve. If peristalsis is diminished, a partial wrap may be preferable. Patients having the factors listed in Table 5 should probably not be managed by surgeons during their initial learning curve of LARS.

Table 4 Indications for Laparoscopic Antireflux Surgery | |

|---|---|

|

Table 5 Relative Contraindications for Laparoscopic Antireflux Surgery | |

|---|---|

|

Basic Tenets of Antireflux Surgery

The basic tenets of LARS include restoration of an effective LES and creation of a gastroesophageal valve. These concepts are based on a variety of considerations that have been touted in the literature, such as the role of an intra-abdominal segment of esophagus, the function of the gastric muscularis used to wrap around the esophagus, and the physiologic implications of the law of Laplace. Almost all antireflux operations involve plicating the lower esophagus with gastric smooth muscle, usually the gastric fundus. The notable exception to performing fundoplication is the Hill esophagogastropexy as described elsewhere in this text.

Fundoplication requires wrapping the fundus itself, not the body of the stomach, around the esophagus, rather than around

the proximal body of the stomach. The fundus, unlike the remainder of the stomach, exhibits a physiologic phenomenon known as receptive relaxation that causes decreased tone of the gastric fundic smooth muscle in association with swallowing-induced relaxation of the LES. If the fundoplication is performed around the stomach rather than the esophagus, periodic contractions of the gastric smooth muscle within the wrap are insufficient to allow free passage of intraluminal contents, and therefore results in dysphagia.

the proximal body of the stomach. The fundus, unlike the remainder of the stomach, exhibits a physiologic phenomenon known as receptive relaxation that causes decreased tone of the gastric fundic smooth muscle in association with swallowing-induced relaxation of the LES. If the fundoplication is performed around the stomach rather than the esophagus, periodic contractions of the gastric smooth muscle within the wrap are insufficient to allow free passage of intraluminal contents, and therefore results in dysphagia.

The fundoplication should reside within the abdomen without tension, and the crura should be closed adequately to prevent migration of the stomach or the fundoplication into the chest. If this occurs, an iatrogenic paraesophageal hernia has been created.

In general, complete (360 degree) fundoplications such as the Nissen fundoplication create more resistance to flow (both prograde, which may result in an increased incidence of dysphagia, and retrograde, as desired to lessen the risk of postoperative reflux) and may be more durable over the long term than partial fundoplications. In contrast, partial fundoplications have less resistance to flow, both prograde and retrograde, and are associated with less postoperative dysphagia but have a greater risk of recurrent reflux or disruption of the wrap.

Choice of Approach

The precise mechanism whereby antireflux surgery exerts its effects remains incompletely understood, and each operation works in a slightly different fashion. Currently, most patients are thought to be best suited to a transabdominal fundoplication, usually an LNF (Table 6). Atypical patients, however, may warrant an alternative approach. Those patients with a short esophagus will require an esophageal-lengthening procedure, either in the form of a laparoscopic Collis gastroplasty or a transthoracic Collis operation. Effort should be made to avoid a lengthening procedure by maximizing the laparoscopic dissection; however, if obtaining 3 cm of intra-abdominal esophagus is not possible, a Collis procedure is necessary. Due to potential acid secretion in the neo-esophagus and the risk of peptic stricture/esophagitis, these patients should be given postoperative PPI therapy. Patients who have undergone previous subdiaphragmatic surgery or have a hostile abdomen from multiple prior operations may also be best served by a transthoracic approach. Individuals who have previously undergone partial gastrectomy may not have adequate fundus to perform a true fundoplication and may require an alternative operation, such as the Hill esophagogastropexy. Patients with morbid obesity and a large left lateral hepatic segment may be impossible to approach laparoscopically because of the inability to expose the esophageal hiatus under the enlarged liver.

Table 6 Choice of Operation for Antireflux Surgery | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Transthoracic

The primary transthoracic operation used for the control of GER has been the Belsey Mark IV (Chapter 64). In this operation, the distal esophagus is mobilized, and the proximal stomach is delivered through the esophageal hiatus. An anterior 270-degree plication of the fundus is performed up onto the esophagus, buttressed by the diaphragmatic crura. The usual mode of access for the Belsey repair has been a left thoracotomy. McKernan and Champion reported early follow-up on a small series of thoracoscopic-modified Belsey fundoplications with excellent results; however, a recent 5-year follow-up demonstrated high morbidity and recurrence.

Transabdominal

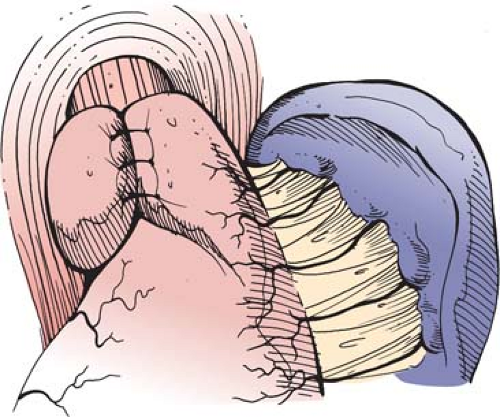

In the total or complete fundoplications, the fundus of the stomach is wrapped circumferentially around the lower esophagus. First described in 1956, the Nissen fundoplication, with various modifications from the original description, has long been the preferred surgical alternative to medical therapy for the treatment of refractory GERD. The fundoplication is accomplished by circumferentially dissecting the distal esophagus, mobilizing the gastric fundus, and plicating the fundus around the lower esophagus, creating a high-pressure zone. This increases the resting tone of the sphincter mechanism and improves its response to elevated intragastric pressure. Nissen’s original description of the operation involved mobilizing the abdominal esophagus and lesser curvature of the proximal stomach and wrapping the posterior wall of the fundus around to join the anterior aspect of the fundus. The newly created fundoplication varied from 3 to 6 cm in length and included the esophageal wall in the fundoplication. Nissen did not describe division of the short gastric vessels using his technique. Two surgeons working with Nissen modified the technique, again without division of the short gastric vessels, to wrap the anterior portion of the fundus around the esophagus such that even less mobilization of the upper stomach was required. This is the Rossetti or Rossetti-Hill modification of the Nissen fundoplication as described in Chapter 66 of this text (Fig. 2).

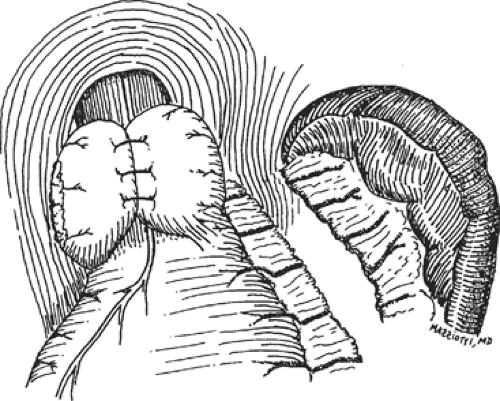

However, most surgeons in the United States today perform a short, floppy Nissen fundoplication. In this modification of the Nissen

fundoplication, the short gastric vessels are divided with full fundic mobilization. The lateral border of the fundus is wrapped around the esophagus and sutured to the anterior edge of the medial fundus, creating a short (<2.5 cm) fundoplication that is usually fashioned over a No. 50 to 60 French esophageal dilator (Fig. 3).

fundoplication, the short gastric vessels are divided with full fundic mobilization. The lateral border of the fundus is wrapped around the esophagus and sutured to the anterior edge of the medial fundus, creating a short (<2.5 cm) fundoplication that is usually fashioned over a No. 50 to 60 French esophageal dilator (Fig. 3).

In the prospective randomized multicenter trial performed by the Veterans Hospital Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Study Group, DeMeester et al. attempted to standardize and improve outcomes by advocating the following technical principles of a Nissen fundoplication:

The right vagus nerve is identified.

The left vagus nerve is identified.

The hepatic branch of the vagus is preserved.

The cardioesophageal fat pad is removed.

The gastric fundus is mobilized by dividing the short gastric vessels.

The crura are closed.

The wrap is placed between the right vagus and esophagus.

Teflon pledgets are used.

A bougie is used to calibrate the wrap diameter.

The length of the wrap is ≤2 cm.

Partial Fundoplications

Partial fundoplications have been used because of concerns that the complete fundoplication may be hypercontinent, leading to some of the well-described postoperative sequelae of the Nissen fundoplication, such as dysphagia, inability to belch, and the gas-bloat syndrome. Partial fundoplications attempt to provide effective reflux prevention with minimal esophageal outflow resistance. In general terms, partial fundoplications are more difficult to conceptualize and perform for the novice surgeon, limiting their widespread application. There are also concerns that the long-term durability of such repairs will not be as good as that for the Nissen fundoplication. Some surgeons use partial fundoplications for all patients who are undergoing antireflux surgery, whereas other surgeons use partial fundoplications in specific situations. Possible indications for selective use of partial fundoplications are listed in Table 7. These include diminished esophageal motility, either primary or secondary, severe aerophagia, reoperative situations, or anatomic conditions that preclude a tension-free complete fundoplication.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree