EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If the patient has acute leg pain and a history of trauma, quickly take his vital signs and determine the leg’s neurovascular status. Observe the patient’s leg position and check for swelling, gross deformities, or abnormal rotation. Also, be sure to check distal pulses and note skin color and temperature. A pale, cool, and pulseless leg may indicate impaired circulation, which may require emergency surgery.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient’s condition permits, ask him when the pain began and have him describe its intensity, character, and pattern. Is the pain worse in the morning, at night, or with movement? If it doesn’t prevent him from walking, must he rely on a crutch or other assistive device? Also ask him about the presence of other signs and symptoms.

Find out if the patient has a history of leg injury or surgery and if he or a family member has a history of joint, vascular, or back problems. Also ask which medications he’s taking and whether they have helped to relieve his leg pain.

Begin the physical examination by watching the patient walk, if his condition permits. Observe how he holds his leg while standing and sitting. Palpate the legs, buttocks, and lower back to determine the extent of pain and tenderness. If a fracture has been ruled out, test the patient’s range of motion (ROM) in the hip and knee. Also, check reflexes with the patient’s leg straightened and raised, noting action that causes pain. Then compare both legs for symmetry, movement, and active ROM. Additionally, assess sensation and strength. If the patient wears a leg cast, splint, or restrictive dressing, carefully check distal circulation, sensation, and mobility, and stretch his toes to elicit associated pain.

Medical Causes

- Bone cancer. Continuous deep or boring pain, commonly worse at night, may be the first symptom of bone cancer. Later, swelling, increased pain with activity, and a palpable lump or mass may occur. The patient may also complain of impaired mobility to the affected limb.

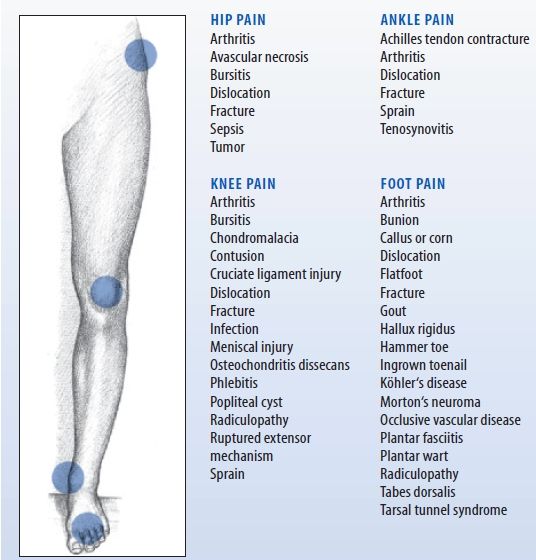

Highlighting Causes of Local Leg Pain

Various disorders cause hip, knee, ankle, or foot pain, which may radiate to surrounding tissues and be reported as leg pain. Local pain is commonly accompanied by tenderness, swelling, and deformity in the affected area.

- Compartment syndrome. Progressive, intense lower leg pain that increases with passive muscle stretching is a cardinal sign of compartment syndrome, a limb-threatening disorder. Restrictive dressings or traction may aggravate the pain, which typically worsens despite analgesic administration. Other findings include muscle weakness and paresthesia but apparently normal distal circulation. With irreversible muscle ischemia, paralysis and an absent pulse also occur.

- Fracture. Severe, acute pain accompanies swelling and ecchymosis in the affected leg. Movement produces extreme pain, and the leg may be unable to bear weight. Neurovascular status distal to the fracture may be impaired, causing paresthesia, an absent pulse, mottled cyanosis, and cool skin. Deformity, muscle spasms, and bony crepitation may also occur.

- Infection. Local leg pain, erythema, swelling, streaking, and warmth characterize soft tissue and bone infections. A fever and tachycardia may be present with other systemic signs.

- Occlusive vascular disease. Continuous cramping pain in the legs and feet may worsen with walking, inducing claudication. The patient may report increased pain at night, cold feet, cold intolerance, numbness, and tingling. Examination may reveal ankle and lower leg edema, decreased or absent pulses, and increased capillary refill time. (Normal time is less than 3 seconds.)

- Sciatica. Pain, described as shooting, aching, or tingling, radiates down the back of the leg along the sciatic nerve. Typically, activity exacerbates the pain and rest relieves it. The patient may limp to avoid exacerbating the pain and may have difficulty moving from a sitting to a standing position.

- Strain or sprain. Acute strain causes sharp, transient pain and rapid swelling, followed by leg tenderness and ecchymosis. Chronic strain produces stiffness, soreness, and generalized leg tenderness several hours after the injury; active and passive motion may be painful or impossible. A sprain causes local pain, especially during joint movement; ecchymosis and, possibly, local swelling and loss of mobility develop.

- Thrombophlebitis. Discomfort may range from calf tenderness to severe pain accompanied by swelling, warmth, and a feeling of heaviness in the affected leg. The patient may also develop a fever, chills, malaise, muscle cramps, and a positive Homans’ sign. Assessment may reveal superficial veins that are visibly engorged; palpable, hard, thready, and cordlike; and sensitive to pressure.

- Varicose veins. Mild to severe leg symptoms may develop, including nocturnal cramping; a feeling of heaviness; diffuse, dull aching after prolonged standing or walking; and aching during menses. Assessment may reveal palpable nodules, orthostatic edema, and stasis pigmentation of the calves and ankles.

GENDER CUE

GENDER CUE

Primary varicose veins originate in the superficial system and are more common in women.

- Venous stasis ulcer. Localized pain and bleeding arise from infected ulcerations on the lower extremities. Mottled, bluish pigmentation is characteristic, and local edema may occur.

Special Considerations

If the patient has acute leg pain, closely monitor his neurovascular status by frequently checking distal pulses and evaluating the legs for temperature, color, and sensation. Also monitor his thigh and calf circumference to evaluate bleeding into tissues from a possible fracture site. Prepare the patient for X-rays. Use sandbags to immobilize his leg; apply ice and, if needed, skeletal traction. If a fracture isn’t suspected, prepare the patient for laboratory tests to detect an infectious agent or for venography, Doppler ultrasonography, plethysmography, or angiography to determine vascular competency. Withhold food and fluids until the need for surgery has been ruled out, and withhold analgesics until a preliminary diagnosis is made. Administer an anticoagulant and antibiotic as needed.

Patient Counseling

Explain the use of anti-inflammatory drugs, ROM exercises, and assistive devices. Discuss the need for physical therapy, as appropriate, and lifestyle changes the patient should make.

Pediatric Pointers

Common pediatric causes of leg pain include a fracture, osteomyelitis, and bone cancer. If parents fail to give an adequate explanation for a leg fracture, consider the possibility of child abuse.

REFERENCES

Konstantinou, K., Hider, S. L., Jordan, J. L., Lewis, M., Dunn, K. M., & Hay, E. M. (2013). The impact of low back-related leg pain on outcomes as compared with low back pain alone: A systematic review of the literature. Clinical Journal of Pain, 29(7), 644–654.

Schafer, A., Hall, T., & Briffa, K. (2009). Classification of low back-related leg pain—A proposed patho-mechanism-based approach. Manual Therapy, 14(2), 222–230.

Level of Consciousness, Decreased

A decrease in the level of consciousness (LOC), from lethargy to stupor to coma, usually results from a neurologic disorder and may signal a life-threatening complication, such as hemorrhage, trauma, or cerebral edema. However, this sign can also result from a metabolic, GI, musculoskeletal, urologic, or cardiopulmonary disorder; severe nutritional deficiency; the effects of toxins; or drug use. LOC can deteriorate suddenly or gradually and can remain altered temporarily or permanently.

Consciousness is affected by the reticular activating system (RAS), an intricate network of neurons with axons extending from the brain stem, thalamus, and hypothalamus to the cerebral cortex. A disturbance in any part of this integrated system prevents the intercommunication that makes consciousness possible. Loss of consciousness can result from a bilateral cerebral disturbance, an RAS disturbance, or both. Cerebral dysfunction characteristically produces the least dramatic decrease in a patient’s LOC. In contrast, dysfunction of the RAS produces the most dramatic decrease in LOC — coma.

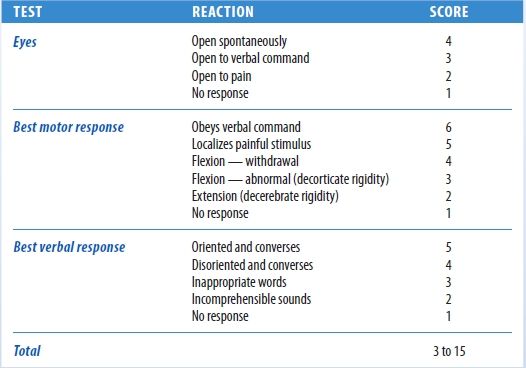

The most sensitive indicator of a decreased LOC is a change in the patient’s mental status. The Glasgow Coma Scale, which measures a patient’s ability to respond to verbal, sensory, and motor stimulation, can be used to quickly evaluate a patient’s LOC.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

After evaluating the patient’s airway, breathing, and circulation, use the Glasgow Coma Scale to quickly determine his LOC and to obtain baseline data. (See Glasgow Coma Scale.) If the patient’s score is 13 or less, emergency surgery may be necessary. Insert an artificial airway, elevate the head of the bed 30 degrees and, if spinal cord injury has been ruled out, turn the patient’s head to the side. Prepare to suction the patient if necessary. You may need to hyperventilate him to reduce carbon dioxide levels and decrease intracranial pressure (ICP). Then determine the rate, rhythm, and depth of spontaneous respirations. Support his breathing with a handheld resuscitation bag, if necessary. If the patient’s Glasgow Coma Scale score is 7 or less, intubation and resuscitation may be necessary.

Continue to monitor the patient’s vital signs, being alert for signs of increasing ICP, such as bradycardia and a widening pulse pressure. When his airway, breathing, and circulation are stabilized, perform a neurologic examination.

Glasgow Coma Scale

You‘ve probably heard such terms as lethargic, obtunded, and stuporous used to describe a progressive decrease in a patient‘s level of consciousness (LOC). However, the Glasgow Coma Scale provides a more accurate, less subjective method of recording such changes, grading consciousness in relation to eye opening and motor and verbal responses.

To use the Glasgow Coma Scale, test the patient‘s ability to respond to verbal, motor, and sensory stimulation. The scoring system doesn‘t determine the exact LOC, but it does provide an easy way to describe the patient‘s basic status and helps to detect and interpret changes from baseline findings. A decreased reaction score in one or more categories may signal an impending neurologic crisis. A score of 7 or less indicates severe neurologic damage.

History and Physical Examination

Try to obtain history information from the patient, if he’s lucid, and from his family. Did the patient complain of a headache, dizziness, nausea, vision or hearing disturbances, weakness, fatigue, or other problems before his LOC decreased? Has his family noticed changes in the patient’s behavior, personality, memory, or temperament? Also ask about a history of neurologic disease, cancer, or recent trauma or infections; prescribed medications; drug and alcohol use; and the development of other signs and symptoms.

Because a decreased LOC can result from a disorder affecting virtually any body system, tailor the remainder of your evaluation according to the patient’s associated symptoms.

Medical Causes

- Adrenal crisis. A decreased LOC, ranging from lethargy to coma, may develop within 8 to 12 hours of its onset. Early associated findings include progressive weakness, irritability, anorexia, a headache, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and a fever. Later signs and symptoms include hypotension; a rapid, thready pulse; oliguria; cool, clammy skin; and flaccid extremities. The patient with chronic adrenocortical hypofunction may have hyperpigmented skin and mucous membranes.

- Brain abscess. A decreased LOC varies from drowsiness to deep stupor, depending on the abscess size and site. Early signs and symptoms — a constant intractable headache, nausea, vomiting, and seizures — reflect increasing ICP. Typical later features include ocular disturbances (nystagmus, vision loss, and pupillary inequality) and signs of infection such as a fever. Other findings may include personality changes, confusion, abnormal behavior, dizziness, facial weakness, aphasia, ataxia, tremor, and hemiparesis.

- Brain tumor. The patient’s LOC decreases slowly, from lethargy to coma. He may also experience apathy, behavior changes, memory loss, a decreased attention span, a morning headache, dizziness, vision loss, ataxia, and sensorimotor disturbances. Aphasia and seizures are possible, along with signs of hormonal imbalance, such as fluid retention or amenorrhea. Signs and symptoms vary according to the location and size of the tumor. In later stages, papilledema, vomiting, bradycardia, and a widening pulse pressure also appear. In the final stages, the patient may exhibit decorticate or decerebrate posture.

- Cerebral aneurysm (ruptured). Somnolence, confusion and, at times, stupor characterize a moderate bleed; deep coma occurs with severe bleeding, which can be fatal. The onset is usually abrupt, with a sudden, severe headache and nausea and vomiting. Nuchal rigidity, back and leg pain, a fever, restlessness, irritability, occasional seizures, and blurred vision point to meningeal irritation. The type and severity of other findings vary with the site and severity of the hemorrhage and may include hemiparesis, hemisensory defects, dysphagia, and visual defects.

- Diabetic ketoacidosis. Diabetic ketoacidosis produces a rapid decrease in the patient’s LOC, ranging from lethargy to coma, commonly preceded by polydipsia, polyphagia, and polyuria. The patient may complain of weakness, anorexia, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. He may also exhibit orthostatic hypotension; a fruity breath odor; Kussmaul’s respirations; warm, dry skin; and a rapid, thready pulse. Untreated, this condition invariably leads to coma and death.

- Encephalitis. Within 24 to 48 hours after onset, the patient may develop changes in his LOC ranging from lethargy to coma. Other possible findings include an abrupt onset of a fever, a headache, nuchal rigidity, nausea, vomiting, irritability, personality changes, seizures, aphasia, ataxia, hemiparesis, nystagmus, photophobia, myoclonus, and cranial nerve palsies.

- Encephalomyelitis (postvaccinal). Postvaccinal encephalomyelitis is a life-threatening disorder that produces rapid deterioration in the patient’s LOC, from drowsiness to coma. He also experiences a rapid onset of a fever, a headache, nuchal rigidity, back pain, vomiting, and seizures.

- Encephalopathy. With hepatic encephalopathy, signs and symptoms develop in four stages: in the prodromal stage, slight personality changes (disorientation, forgetfulness, slurred speech) and slight tremor; in the impending stage, tremor progressing to asterixis (the hallmark of hepatic encephalopathy), lethargy, aberrant behavior, and apraxia; in the stuporous stage, stupor and hyperventilation, with the patient noisy and abusive when aroused; in the comatose stage, coma with decerebrate posture, hyperactive reflexes, a positive Babinski’s reflex, and fetor hepaticus.

With life-threatening hypertensive encephalopathy, the LOC progressively decreases from lethargy to stupor to coma. Besides markedly elevated blood pressure, the patient may experience a severe headache, vomiting, seizures, vision disturbances, transient paralysis and, eventually, Cheyne-Stokes respirations.

With hypoglycemic encephalopathy, the patient’s LOC rapidly deteriorates from lethargy to coma. Early signs and symptoms include nervousness, restlessness, agitation, and confusion; hunger; alternate flushing and cold sweats; and a headache, trembling, and palpitations. Blurred vision progresses to motor weakness, hemiplegia, dilated pupils, pallor, a decreased pulse rate, shallow respirations, and seizures. Flaccidity and decerebrate posture appear late.

Depending on its severity, hypoxic encephalopathy produces a sudden or gradual decrease in the LOC, leading to coma and brain death. Early on, the patient appears confused and restless, with cyanosis and increased heart and respiratory rates and blood pressure. Later, his respiratory pattern becomes abnormal, and assessment reveals a decreased pulse, blood pressure, and deep tendon reflexes (DTRs); a positive Babinski’s reflex; an absent doll’s eye sign; and fixed pupils.

With uremic encephalopathy, the LOC decreases gradually from lethargy to coma. Early on, the patient may appear apathetic, inattentive, confused, and irritable and may complain of a headache, nausea, fatigue, and anorexia. Other findings include vomiting, tremors, edema, papilledema, hypertension, cardiac arrhythmias, dyspnea, crackles, oliguria, and Kussmaul’s and Cheyne-Stokes respirations.

- Heatstroke. As body temperature increases, the patient’s LOC gradually decreases from lethargy to coma. Early signs and symptoms include malaise, tachycardia, tachypnea, orthostatic hypotension, muscle cramps, rigidity, and syncope. The patient may be irritable, anxious, and dizzy and may report a severe headache. At the onset of heatstroke, the patient’s skin is hot, flushed, and diaphoretic with blotchy cyanosis; later, when his fever exceeds 105°F (40.5°C), his skin becomes hot, flushed, and anhidrotic. Pulse and respiratory rate increase markedly, and blood pressure drops precipitously. Other findings include vomiting, diarrhea, dilated pupils, and Cheyne-Stokes respirations.

- Hypernatremia. Hypernatremia, life threatening if acute, causes the patient’s LOC to deteriorate from lethargy to coma. He is irritable and exhibits twitches progressing to seizures. Other associated signs and symptoms include a weak, thready pulse; nausea; malaise; a fever; thirst; flushed skin; and dry mucous membranes.

- Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic nonketotic syndrome. LOC decreases rapidly from lethargy to coma. Early findings include polyuria, polydipsia, weight loss, and weakness. Later, the patient may develop hypotension, poor skin turgor, dry skin and mucous membranes, tachycardia, tachypnea, oliguria, and seizures.

- Hypokalemia. LOC gradually decreases to lethargy; coma is rare. Other findings include confusion, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and polyuria; weakness, decreased reflexes, and malaise; and dizziness, hypotension, arrhythmias, and abnormal electrocardiogram results.

- Hyponatremia. Hyponatremia, life threatening if acute, produces a decreased LOC in late stages. Early nausea and malaise may progress to behavior changes, confusion, lethargy, incoordination and, eventually, seizures and coma.

- Hypothermia. With severe hypothermia (temperature below 90°F [32.2°C]), the patient’s LOC decreases from lethargy to coma. DTRs disappear, and ventricular fibrillation occurs, possibly followed by cardiopulmonary arrest. With mild to moderate hypothermia, the patient may experience memory loss and slurred speech as well as shivering, weakness, fatigue, and apathy. Other early signs and symptoms include ataxia, muscle stiffness, and hyperactive DTRs; diuresis; tachycardia and decreased respiratory rate and blood pressure; and cold, pale skin. Later, muscle rigidity and decreased reflexes may develop, along with peripheral cyanosis, bradycardia, arrhythmias, severe hypotension, a decreased respiratory rate with shallow respirations, and oliguria.

- Intracerebral hemorrhage. Intracerebral hemorrhage is a life-threatening disorder that produces a rapid, steady loss of consciousness within hours, commonly accompanied by a severe headache, dizziness, nausea, and vomiting. Associated signs and symptoms vary and may include increased blood pressure, irregular respirations, a positive Babinski’s reflex, seizures, aphasia, decreased sensations, hemiplegia, decorticate or decerebrate posture, and dilated pupils.

- Listeriosis. If listeriosis spreads to the nervous system and causes meningitis, signs and symptoms include a decreased LOC, a fever, a headache, and nuchal rigidity. Early signs and symptoms of listeriosis include a fever, myalgia, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

GENDER CUE

GENDER CUE

Infections during pregnancy may lead to premature delivery, infection of the neonate, or stillbirth.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree