Patient Story

A 64-year-old black woman presents to the office with itching keloids on her chest (Figure 204-1). The horizontal keloid started during childhood when she was scratched by a branch of a tree. The vertical keloid is the result of bypass surgery 1 year ago. The lower portion of this area could be called a hypertrophic scar as it does not advance beyond the borders of the original surgery. The patient was happy to receive intralesional steroids to decrease her symptoms. Intralesional triamcinolone did, in fact, decrease the itching and flatten the vertical keloid.

Introduction

Epidemiology

- Individuals with darker pigmentation are more likely to develop keloids. Sixteen percent of black persons reported having keloids in a random sampling.1

- Men and women are generally affected equally except that keloids are more common in young adult women—probably secondary to a higher rate of piercing the ears (Figure 204-2).2

- Highest incidence is in individuals ages 10 to 20 years.2,3

Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Keloids are dermal fibrotic lesions that are a variation of the normal wound-healing process in the spectrum of fibroproliferative disorders.

- Keloids are more likely to develop in areas of the body that are subjected to high skin tension such as over the sternum (Figure 204-1).

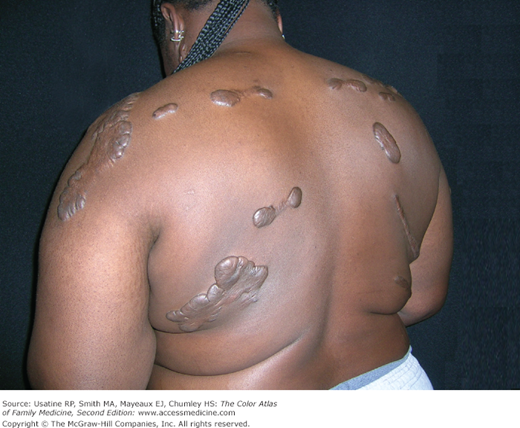

- These can occur even up to a year after the injury and will enlarge beyond the scar margin. Burns and other injuries can heal with a keloid in just one portion of the area injured (Figure 204-3).

- Wounds subjected to prolonged inflammation (acne cysts) are more likely to develop keloids.

Risk Factors

- Darker skin pigmentation (African, Hispanic, or Asian ethnicity).

- A family history of keloids.

- Wound healing by secondary intention.

- Wounds subjected to prolonged inflammation.

- Sites of repeated trauma.

- Pregnancy.

- Body piercings (Figure 204-4).

Diagnosis

- Some keloids present with pruritic pain or a burning sensation around the scar.

- Initially manifest as erythematous lesions devoid of hair follicles or other glandular tissue.

- Papules to nodules to large tuberous lesions (Figure 204-5).

- Range in consistency from soft and doughy to rubbery and hard. Most often, the lesions are the color of normal skin but can become brownish red or bluish and then pale as they age.4

- May extend in a claw-like fashion far beyond any slight injury.

- Lesions on neck, ears, and abdomen tend to become pedunculated.

- Anterior chest, shoulders, flexor surfaces of extremities, anterior neck, earlobes, and wounds that cross skin tension lines.

Differential Diagnosis

- Hypertrophic scars can appear similar to keloids but are confined to the site of original injury.

- Acne keloidalis nuchae is an inflammatory disorder around hair follicles of the posterior neck that results in keloidal scarring (Figure 204-6). Although the scarring is similar to keloids the location and pathophysiology are unique. This process can also cause alopecia (Chapter 114, Pseudofolliculitis and Acne Keloidalis Nuchae).

- Dermatofibromas are common button-like dermal nodules usually found on the legs or arms. They may umbilicate when the surrounding skin is pinched. These often have a hyperpigmented halo around them and are less elevated than keloids (Chapter 160, Dermatofibroma).

- Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a malignant version of the dermatofibroma. It usually presents as an atrophic, scar-like lesion developing into an enlarging firm and irregular nodular mass. If this is suspected, a biopsy is needed (Chapter 160, Dermatofibroma).