Hepatic cancer (primary liver cancer or another cancer that has metastasized to the liver) may cause jaundice by causing obstruction of the bile duct. Even advanced cancer causes nonspecific signs and symptoms, such as right upper quadrant discomfort and tenderness, nausea, weight loss, and a slight fever. Examination may reveal irregular, nodular, firm hepatomegaly; ascites; peripheral edema; a bruit heard over the liver; and a right upper quadrant mass.

With pancreatic cancer, progressive jaundice — possibly with pruritus — may be the only sign. Related early findings are nonspecific, such as weight loss and back or abdominal pain. Other signs and symptoms include anorexia, nausea and vomiting, a fever, steatorrhea, fatigue, weakness, diarrhea, pruritus, and skin lesions (usually on the legs).

Jaundice: Impaired Bilirubin Metabolism

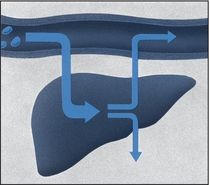

Jaundice occurs in three forms: prehepatic, hepatic, and posthepatic. In all three, bilirubin levels in the blood increase due to impaired metabolism.

With prehepatic jaundice, certain conditions and disorders, such as transfusion reactions and sickle cell anemia, cause massive hemolysis. Red blood cells rupture faster than the liver can conjugate bilirubin, so large amounts of unconjugated bilirubin pass into the blood, causing increased intestinal conversion of this bilirubin to water-soluble urobilinogen for excretion in urine and stools. (Unconjugated bilirubin is insoluble in water, so it can’t be directly excreted in urine.)

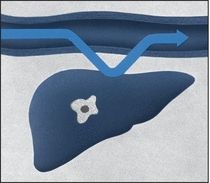

Hepatic jaundice results from the liver’s inability to conjugate or excrete bilirubin, leading to increased blood levels of conjugated and unconjugated bilirubin. This occurs with such disorders as hepatitis, cirrhosis, and metastatic cancer and during the prolonged use of drugs metabolized by the liver.

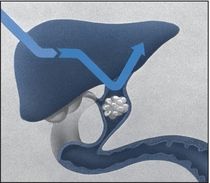

With posthepatic jaundice, which occurs in patients with a biliary or pancreatic disorder, bilirubin forms at its normal rate, but inflammation, scar tissue, a tumor, or gallstones block the flow of bile into the intestine. This causes an accumulation of conjugated bilirubin in the blood. Water-soluble, conjugated bilirubin is excreted in urine.

- Cholangitis. Obstruction and infection in the common bile duct cause Charcot’s triad: jaundice, right upper quadrant pain, and a high fever with chills.

- Cholecystitis. Cholecystitis produces nonobstructive jaundice in about 25% of patients. Biliary colic typically peaks abruptly, persisting for 2 to 4 hours. The pain then localizes to the right upper quadrant and becomes constant. Local inflammation or passage of stones to the common bile duct causes jaundice. Other findings include nausea, vomiting (usually indicating the presence of a stone), a fever, profuse diaphoresis, chills, tenderness on palpation, a positive Murphy’s sign and, possibly, abdominal distention and rigidity.

- Cholelithiasis. Cholelithiasis commonly causes jaundice and biliary colic. It’s characterized by severe, steady pain in the right upper quadrant or epigastrium that radiates to the right scapula or shoulder and intensifies over several hours. Accompanying signs and symptoms include nausea and vomiting, tachycardia, and restlessness. Occlusion of the common bile duct causes a fever, chills, jaundice, clay-colored stools, and abdominal tenderness. After consuming a fatty meal, the patient may experience vague epigastric fullness and dyspepsia.

- Cirrhosis. With Laënnec’s cirrhosis, mild to moderate jaundice with pruritus usually signals hepatocellular necrosis or progressive hepatic insufficiency. Common early findings include ascites, weakness, leg edema, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea or constipation, anorexia, weight loss, and right upper quadrant pain. Massive hematemesis and other bleeding tendencies may also occur. Other findings include an enlarged liver and parotid gland, clubbed fingers, Dupuytren’s contracture, mental changes, asterixis, fetor hepaticus, spider angiomas, and palmar erythema. Males may exhibit gynecomastia, scanty chest and axillary hair, and testicular atrophy; females may experience menstrual irregularities.

With primary biliary cirrhosis, fluctuating jaundice may appear years after the onset of other signs and symptoms, such as pruritus that worsens at bedtime (commonly the first sign), weakness, fatigue, weight loss, and vague abdominal pain. Itching may lead to skin excoriation. Associated findings include hyperpigmentation; indications of malabsorption, such as nocturnal diarrhea, steatorrhea, purpura, and osteomalacia; hematemesis from esophageal varices; ascites; edema; xanthelasmas; xanthomas on the palms, soles, and elbows; and hepatomegaly.

- Dubin-Johnson syndrome. With Dubin-Johnson syndrome, which is a rare, chronic inherited syndrome, fluctuating jaundice that increases with stress is the major sign, appearing as late as age 40. Related findings include slight hepatic enlargement and tenderness, upper abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting.

- Heart failure. Jaundice due to liver dysfunction occurs in patients with severe right-sided heart failure. Other effects include jugular vein distention, cyanosis, dependent edema of the legs and sacrum, steady weight gain, confusion, hepatomegaly, nausea and vomiting, abdominal discomfort, and anorexia due to visceral edema. Ascites are a late sign. Oliguria, marked weakness, and anxiety may also occur. If left-sided heart failure develops first, other findings may include fatigue, dyspnea, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, tachypnea, arrhythmias, and tachycardia.

- Hepatic abscess. Multiple abscesses may cause jaundice, but the primary effects are a persistent fever with chills and sweating. Other findings include steady, severe pain in the right upper quadrant or midepigastrium that may be referred to the shoulder; nausea and vomiting; anorexia; hepatomegaly; an elevated right hemidiaphragm; and ascites.

- Hepatitis. Dark urine and clay-colored stools usually develop before jaundice in the late stages of acute viral hepatitis. Early systemic signs and symptoms vary and include fatigue, nausea, vomiting, malaise, arthralgia, myalgia, a headache, anorexia, photophobia, pharyngitis, a cough, diarrhea or constipation, and a low-grade fever associated with liver and lymph node enlargement. During the icteric phase (which subsides within 2 to 3 weeks unless complications occur), systemic signs subside, but an enlarged, palpable liver may be present along with weight loss, anorexia, and right upper quadrant pain and tenderness.

- Pancreatitis (acute). Edema of the head of the pancreas and obstruction of the common bile duct can cause jaundice; however, the primary symptom of acute pancreatitis is usually severe epigastric pain that commonly radiates to the back. Lying with the knees flexed on the chest or sitting up and leaning forward brings relief. Early associated signs and symptoms include nausea, persistent vomiting, abdominal distention, and Turner’s or Cullen’s sign. Other findings include a fever, tachycardia, abdominal rigidity and tenderness, hypoactive bowel sounds, and crackles.

Severe pancreatitis produces extreme restlessness; mottled skin; cold, diaphoretic extremities; paresthesia; and tetany — the last two being symptoms of hypocalcemia. Fulminant pancreatitis causes massive hemorrhage.

- Sickle cell anemia. Hemolysis produces jaundice in the patient with sickle cell anemia. Other findings include impaired growth and development, increased susceptibility to infection, life-threatening thrombotic complications, and, commonly, leg ulcers, swollen (painful) joints, a fever, and chills. Bone aches and chest pain may also occur. Severe hemolysis may cause hematuria and pallor, chronic fatigue, weakness, dyspnea (or dyspnea on exertion), and tachycardia. The patient may also have splenomegaly. During a sickle cell crisis, the patient may have severe bone, abdominal, thoracic, and muscular pain; a low-grade fever; and increased weakness, jaundice, and dyspnea.

Other Causes

- Drugs. Many drugs may cause hepatic injury and resultant jaundice. Examples include acetaminophen, phenylbutazone, I.V. tetracycline, isoniazid, hormonal contraceptives, sulfonamides, mercaptopurine, erythromycin estolate, niacin, troleandomycin, androgenic steroids, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl reductase inhibitors, phenothiazines, ethanol, methyldopa, rifampin, and Dilantin.

- Treatments. Upper abdominal surgery may cause postoperative jaundice, which occurs secondary to hepatocellular damage from the manipulation of organs, leading to edema and obstructed bile flow; from the administration of halothane; or from prolonged surgery resulting in shock, blood loss, or blood transfusion.

A surgical shunt used to reduce portal hypertension (such as a portacaval shunt) may also produce jaundice.

Special Considerations

To help decrease pruritus, frequently bathe the patient; apply an antipruritic lotion, such as calamine; and administer diphenhydramine or hydroxyzine. Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests to evaluate biliary and hepatic function. Laboratory studies include urine and fecal urobilinogen, serum bilirubin, liver enzyme, and cholesterol levels; prothrombin time; and a complete blood count. Other tests include ultrasonography, cholangiography, liver biopsy, and exploratory laparotomy.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient appropriate dietary changes he can make, and discuss ways to reduce pruritus.

Pediatric Pointers

Physiologic jaundice is common in neonates, developing 3 to 5 days after birth. In infants, obstructive jaundice usually results from congenital biliary atresia. A choledochal cyst — a congenital cystic dilation of the common bile duct — may also cause jaundice in children, particularly those of Japanese descent.

The list of other causes of jaundice is extensive and includes, but isn’t limited to, Crigler-Najjar syndrome, Gilbert’s disease, Rotor’s syndrome, thalassemia major, hereditary spherocytosis, erythroblastosis fetalis, Hodgkin’s disease, infectious mononucleosis, Wilson’s disease, amyloidosis, and Reye’s syndrome.

Geriatric Pointers

In patients older than age 60, jaundice is usually caused by cholestasis resulting from extrahepatic obstruction.

REFERENCES

Liebel, F., Kaur, S., Ruvolo, E., Kollias, N., & Southall, M. D. (2012). Irradiation of skin with visible light induces reactive oxygen species and matrix-degrading enzymes. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 132, 1901–1907.

Stokowski, L. A. (2011). Fundamentals of phototherapy for neonatal jaundice. Advances in Neonatal Care, 11, 10–21.

Jaw Pain

Jaw pain may arise from either of the two bones that hold the teeth in the jaw — the maxilla (upper jaw) and the mandible (lower jaw). Jaw pain also includes pain in the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), where the mandible meets the temporal bone.

Jaw pain may develop gradually or abruptly and may range from barely noticeable to excruciating, depending on its cause. It usually results from disorders of the teeth, soft tissue, or glands of the mouth or throat or from local trauma or infection. Systemic causes include musculoskeletal, neurologic, cardiovascular, endocrine, immunologic, metabolic, and infectious disorders. Life-threatening disorders, such as a myocardial infarction (MI) and tetany, also produce jaw pain as well as certain drugs (especially phenothiazines) and dental or surgical procedures.

Jaw pain is seldom a primary indicator of any one disorder; however, some causes are medical emergencies.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

Ask the patient when the jaw pain began. Did it arise suddenly or gradually? Is it more severe or frequent now than when it first occurred? Sudden severe jaw pain, especially when associated with chest pain, shortness of breath, or arm pain, requires prompt evaluation because it may herald a life-threatening myocardial infarction. Perform an electrocardiogram and obtain blood samples for cardiac enzyme levels. Administer oxygen, morphine sulfate, and a vasodilator as indicated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree