Classification

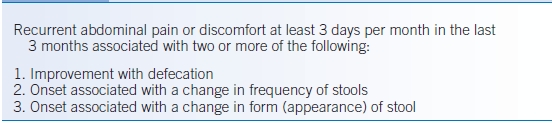

- Several historical diagnostic criteria for IBS exist, with the Rome III criteria (Table 32-2) representing the most recent and encompassing criteria.1 It should be noted that these criteria were devised primarily as a tool for devising clinical studies in the area. However, when applied to clinical practice, they have a high positive predictive value (>95%).

TABLE 32-2 The Rome III Irritable Bowel Syndrome Criteria

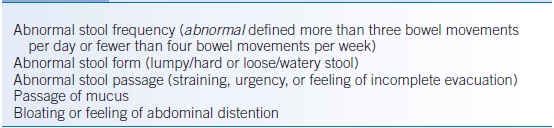

- Although they are not necessary for IBS diagnosis, several supporting symptoms (Table 32-3) help to solidify the diagnosis and further characterize the disorder into IBS with constipation (IBS-C), IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D), mixed IBS (IBS-M), or unsubtyped IBS (IBS-U).

TABLE 32-3 Supportive Symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Epidemiology

- IBS is frequently seen in both primary care and specialty care settings and is one of the most common diagnoses seen by gastroenterologists.3

- Estimates place the prevalence of IBS anywhere from 1% to 20% worldwide.

- Systematic reviews suggest that 10% to 15% of the adult US population are affected with IBS.4

- Population surveys of adults have shown IBS to be more prevalent in women than in men with a ratio of 3 to 4:1.

- Symptom onset tends to occur between the ages of 20 and 40 but can occur at any age. When considering a new diagnosis of IBS in older individuals, exclusion of other mimicking conditions is requisite (e.g., celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth [SIBO]).

- Estimates place the prevalence of IBS anywhere from 1% to 20% worldwide.

- Surveys from both the United States and United Kingdom report an average disease duration of 11 years, although about one-third of patients have symptoms for even longer periods.

- As few as one in three individuals affected with IBS in the United States actually seek medical attention, and the vast majority of these are managed by their primary care physician. Still, the cost to society is considerable, accounting for approximately 3.6 million physician visits and $1.6 billion in direct medical costs each year.

- The burden on the patient is also considerable with health-related quality-of-life (HRQOL) scores similar to patients with diabetes and worse than patients with chronic kidney disease and gastroesophageal reflux disease.5

Pathophysiology

- No single pathophysiologic abnormality has been found that adequately explains the manifestations of IBS. Given the symptomatic basis on which the diagnosis is made, more than one pathophysiologic mechanism likely plays a role. Multiple factors, including abnormalities of intestinal motility, visceral hypersensitivity, GI tract inflammatory processes, disturbances along the brain-gut axis, and psychological factors, have been examined as potentially causative in IBS.6

- A portion of patients with IBS will exhibit exaggerated motility and sensory responses to stressors, meals, and balloon inflation in the GI tract; however, these are neither uniformly identifiable in IBS patients nor consistently reproducible in the same individual.

- IBS may result from sensitization of afferent neural pathways from the gut such that normal intestinal stimuli induce pain.

- Intestinal inflammation also has been hypothesized as playing a role in the development of IBS, particularly as it relates to persistent neuroimmune interactions following infectious gastroenteritis (so-called postinfectious IBS); approximately one-third of patients with IBS report symptom onset after an episode of acute gastroenteritis.

- The role of SIBO or lower levels of bacterial colonization (intestinal dysbiosis) in the development of IBS has been a focus of recent investigations, but its role remains to be fully understood.7

- The central nervous system (and its interpretation of peripheral enteric nerve signals) is receiving increasing attention in investigational settings because of the potential mechanistic significance in IBS.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

- IBS is a symptom-based diagnosis. Patients should report abdominal discomfort and a temporal association with alterations in stool pattern, improvement with bowel movement, or both.

- IBS diagnosis requires an element of chronicity (per Rome criteria, ≥3 days per month over the preceding 3 months), with symptom onset at least 6 months prior to diagnosis.

- The diagnosis of IBS should be made after organic or structural causes have been considered, necessitating a careful search for alarm symptoms before establishing a diagnosis of IBS.

- Important alarm symptoms include unintentional weight loss of ≥10 pounds, recurrent fever, persistent diarrhea, hematochezia, age >50 years at onset of symptoms, male sex, and family history of GI malignancy, inflammatory bowel disease, or celiac sprue.

- A brief history of rapidly progressive symptoms suggests organic disease. The presence of any alarm features warrants a more detailed investigation before diagnosing as IBS.

- Important alarm symptoms include unintentional weight loss of ≥10 pounds, recurrent fever, persistent diarrhea, hematochezia, age >50 years at onset of symptoms, male sex, and family history of GI malignancy, inflammatory bowel disease, or celiac sprue.

- Likewise, the physical examination should be focused to exclude organic disease.

- Diffuse abdominal tenderness is commonly present because of the heightened visceral sensitivity noted in this population.

- Physical examination alarm signs include the presence of thyroid abnormalities, organomegaly, abdominal masses, lymphadenopathy, perianal disease, or heme-positive stool.

- Diffuse abdominal tenderness is commonly present because of the heightened visceral sensitivity noted in this population.

Diagnostic Testing

- Laboratory and invasive testing should be kept to a minimum in the absence of alarm symptoms, because extensive or repetitive investigations may be costly and serve only to reinforce illness behavior.

- Initial laboratory testing should include a complete blood count (CBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), and fecal occult blood test (FOBT).

- Testing for celiac sprue should be considered in all IBS patients (particularly in IBS-D and IBS-M) with IgA anti–tissue transglutaminase test (anti-tTG IgA).

- Complete metabolic profile and stool for culture and Clostridium difficile toxin or PCR testing can be ordered if the pretest probability is high enough, but are likely low yield for the majority of IBS patients.

- Colonoscopy and EGD typically are unnecessary in young patients presenting with classic features of IBS without any alarm symptoms.

- Colonoscopy should be performed in all patients >50 or those with positive FOBT.

- In cases of IBS-D or IBS-M, random colonoscopic biopsies should be performed to exclude microscopic colitis.

- Colonoscopy should be performed in all patients >50 or those with positive FOBT.

TREATMENT

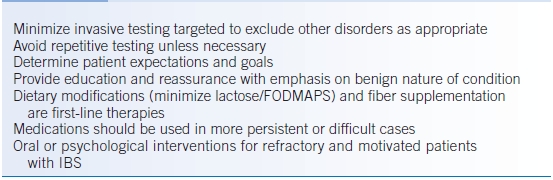

- The approach to therapy in IBS is multifaceted and should be tailored to the patient given the individual’s constellation and severity of symptoms.

- Two key factors determine therapy: dominant symptoms (diarrhea, constipation, pain, others) and symptom severity (intensity, effects on quality of life).

- Current management approaches include behavioral modification, dietary changes, peripherally acting agents, centrally acting agents, and psychological-behavioral therapy.

Medications

- Cases with mild or intermittent symptoms can be managed with symptomatic treatment using peripherally acting agents administered on an as-needed basis.

- Patients with moderate symptoms (as designated by intermittent interference with daily activities) may benefit from regular use of peripheral agents as an initial approach, with the option of introducing centrally acting agents if this approach fails.

- Patients with severe symptoms (regular interference with daily activities, and concurrent affective, personality, and psychosomatic disorders) benefit from combinations of peripheral and central agents but may also need contemporary pharmaceutical agents and psychological approaches to manage their overlapping affective, personality, and psychosomatic disorders.

- Although medical therapy is available and new drugs are currently in development, IBS is a long-term condition with exacerbations and remissions, and medications should be minimized to the extent possible.

- Opioids have no role in the management of IBS. The use of opioids actually may worsen IBS symptoms and provoke so-called narcotic bowel syndrome.8

- Given the lack of identifiable biomarkers, trials of medications are frequently part of the IBS diagnostic process. These trials should be pursued for at least 4 weeks (and ideally 12 weeks) before moving on to different therapy.

- If failure to respond to a single agent in a drug class is experienced, response to a different drug in the same class may still be observed.

- It is important to recognize the substantial (up to 50%) placebo response rates present in this patient population.

- Patient education and reassurance while establishing a therapeutic relationship are cornerstones in the management of this condition. The strength of the physician-patient relationship translates into higher rates of patient satisfaction and fewer return visits.

- Table 32-4 summarizes general management principles for patients with IBS or other functional bowel disorders.

TABLE 32-4 General Approach to Irritable Bowel Syndrome and the Functional Bowel Disorders

FODMAPS, fermentable, oligo-, di-, and monosaccharides and polyols.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree