CHAPTER 6 Investigation and classification of anemia

Definition and causes of anemia

Anemia is defined as a reduction in the concentration of hemoglobin in the peripheral blood below the reference range for the age and gender of an individual (see Table 1.3 for reference ranges). It may be inherited or acquired and results from an imbalance between red cell production and red cell loss (Table 6.1). In general terms the causes of anemia are:

Table 6.1 Mechanisms of anemia

| Mechanism | Pathogenesis |

|---|---|

| Reduced or ineffective erythropoiesis | Decreased marrow erythropoiesis |

| Inadequately increased total erythropoiesis | |

| Increased ineffective erythropoiesis | |

| Increased red cell loss or reduced red cell life span | Acute or chronic blood loss |

| Increased red cell destruction | |

| Splenic pooling and sequestration | |

| Dilutional anemia | Plasma volume expansion |

Clinical features of anemia

A detailed clinical history is critical in determining the cause of anemia. Table 6.2 lists some of the important personal, dietary, drug and family history issues to be explored. The symptoms and signs of anemia result from decreased tissue oxygenation leading to organ dysfunction as well as from adaptive changes, particularly in the cardiovascular system.1,2 The nature and severity of symptoms is influenced by:

Table 6.2 Clinical history in the investigation of anemia

| History | Mechanism | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Current illness | Acute hemorrhage | Epistaxis, menorrhagia, hematemesis, melaena |

| Chronic blood loss | Menorrhagia, melaena | |

| Infection | Parvovirus | |

| Hemolysis | Jaundice | |

| Past medical history | Anemia of chronic disease | Chronic infection Liver disease Renal impairment Hypothyroidism Malignancy |

| Malabsorption | Gastrectomy Gastric bypass Celiac disease Ileal surgery | |

| Travel history | Intra-erythrocytic parasites | Malaria |

| Dietary history | Vegetarian or veganism | Vitamin B12 deficiency |

| Iron intake | Iron deficiency | |

| Excess alcohol | Liver disease | |

| Drugs | Antiplatelet agents | Aspirin, clopidogrel |

| Anticoagulants | Warfarin | |

| Oxidant drugs | Salazopyrin, dapsone | |

| Myelosuppressive agents | Methotrexate Cytotoxic chemotherapy | |

| Exposure to toxins | Toxins or chemicals that interfere with erythropoiesis | Lead, aluminum |

| Family history | Inherited red cell abnormality | Hereditary spherocytosis G6PD deficiency Thalassemia Other hemoglobinopathy |

| Autoimmune disorders | Pernicious anemia Rheumatoid arthritis | |

| Bleeding disorders | Hemophilia von Willebrand disease |

A moderate degree of chronic anemia is usually associated with only mild symptoms accompanied by slight increases in cardiac output at rest and slight decreases in mixed venous PO2. This is because there is a substantial shift of the oxygen dissociation curve to the right (see Chapter 1), mainly due to an adaptive increase in the levels of red cell 2,3-diphosphoglycerate. When the hemoglobin falls below 7–8 g/dl symptoms usually become more marked. The intra-erythrocytic adaptation cannot by itself maintain adequate oxygen delivery to the tissues and other compensatory mechanisms come into effect. These include:

The blood count and red cell indices in anemia

The mean cell volume (MCV) is the most useful red cell parameter for the assessment of the underlying cause of anemia. By using the MCV, anemias can be categorized by red cell size as microcytic (MCV <80 fl), normocytic (normal MCV) or macrocytic (MCV >100 fl). This provides a practical and rapid way of assessing possible causes and guiding further investigations (see below and Table 6.3). The mean cell hemoglobin (MCH) and mean cell hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) are generally of less value than the MCV in the assessment of anemia. The red cell distribution width (RDW), a quantitative measure of the degree of variation in red cell size, can be useful in the assessment of some types of anemia. Usually erythrocytes are of a standard size (6–8 µm) and the RDW is 12–14%. A high RDW indicates that there is variation in erythrocyte size and gives a quantitative measure of anisocytosis. For example, in microcytic anemias, a normal RDW is generally seen in thalassemias whereas in iron deficiency it is mildly elevated. The graphical depiction of red cell features on blood count histograms, such as red cell number versus MCV, may also give an indication of anisocytosis, or the presence of dimorphic populations of erythrocytes.

Table 6.3 Practical classification of anemia based on mean cell volume

| Types | Mean cell volume | Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Microcytic | <80 fl | Iron deficiency Anemia of chronic disease Hemoglobinopathies Hereditary sideroblastic anemia |

| Normocytic | Within reference range (80–100 fl) | Blood loss Hemolysis Failure of erythropoiesis |

| Macrocytic | >80 fl | Deficiency of folate or vitamin B12 Myelodysplasia Liver disease Hypothyroidism |

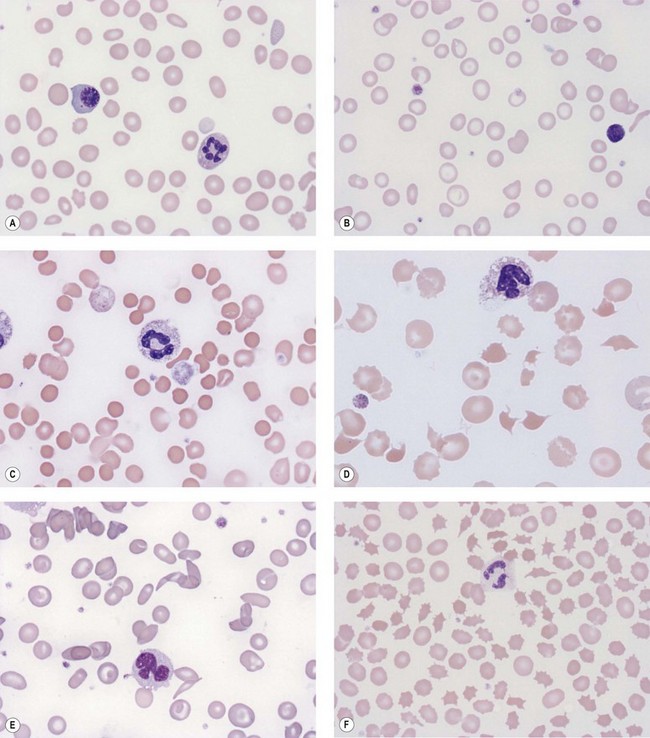

Red cell morphology in anemia

Blood film examination to review red cell morphology has a critical role in the investigation and diagnosis of anemia. The identification of red cell morphological abnormalities may lead to a definitive or differential diagnosis and guide further investigations (Fig. 6.1A–F). The film should be prepared from a freshly collected blood sample, well-stained and coverslipped. Blood stored for >6 hours in anticoagulant prior to the preparation of the film can result in artifacts (e.g. red cell crenation) that can interfere with interpretation of the true red cell morphology. Morphological artifacts can also result from the blood being stored at incorrect temperatures (hot or cold) prior to preparation of the blood film. The film should be examined in an area where only occasional red cells overlap. In such an area normal red cells are primarily round and show a central area of pallor which occupies less than a third of the diameter of the cell. The film should be assessed systematically for:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree