CHAPTER 12 INTRODUCTION TO WELLNESS

WHAT IS ‘WELLNESS’?

In 1961, wellness pioneer Halbert Dunn defined wellness, in his book High-level wellness, as ‘an integrated method of functioning which is oriented toward maximizing the potential of which the individual is capable’ (Dunn 1961, p 4). He acknowledges that wellness is dependent on the relationship between individuals and their environment, stating that wellness ‘requires that the individual maintain a continuum of balance and purposeful direction within the environment where he is functioning’. He also stated that ‘wellness is a direction in progress toward an ever-higher potential of functioning’ (Dunn 1961, p 6).

More recently the [US] President’s Council on Physical Fitness and Sports proposed a uniform definition of wellness as ‘a multidimensional state of being describing the existence of positive health in an individual as exemplified by quality of life and a sense of well-being’ (Corbin & Pangrazi 2001). Yet another definition suggests that wellness is an ‘active process of becoming aware of and making choices toward a more successful existence’ (US National Wellness Institute 2009). Another proposed definition is:

Wellness is the multidimensional state of being ‘well’, where inner and outer worlds are in harmony: a heightened state of consciousness enabling you to be fully present in the moment and respond authentically to any situation from the ‘deep inner well of your being’. Wellness is dynamic and results in a continuous awakening and evolution of consciousness and is the state where you look, feel, perform, and stay ‘well’ and, therefore, experience the greatest fulfilment and enjoyment from life and achieve the greatest longevity. (Cohen 2008a, p 8)

This definition implies that the state of wellness allows the greatest flexibility to respond to situations and therefore provides the greatest resilience to stress and disease. Wellness in this context can be seen as the best preventative medicine. In this definition wellness is also seen as a state of consciousness that guides the quality of our relationships with the world and therefore cannot be viewed separately from the environment in which it occurs. Thus, if ‘health’ is ‘wholeness’, then wellness is the experience of an ever-expanding realisation of what it means to be whole (Cohen 2008a).

Travis and Ryan suggest that wellness is never a static state but rather a way of life, and that wellness and illness exist along a continuum: just as there are degrees of illness, there are also degrees of wellness. Travis and Ryan further see wellness as a choice, a process, a balanced channelling of energy, the integration of body, mind and spirit, and the loving acceptance of self (Travis & Ryan 2004).

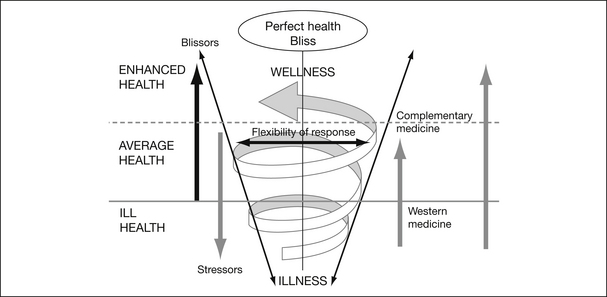

If health and disease are considered to be at opposite ends of a spectrum, then it is possible to classify health into three broad areas: ill health (illness), average health and enhanced health (wellness) (Fig 12.1). The divide between ill health and average health is generally defined in Western medical terms, which classify diseases based on symptom patterns or other diagnostic parameters. Western medicine uses a bottom-up approach that aims to define and understand illness, and develop interventions such as drugs and surgery to treat or prevent the disease and control factors that reduce wellbeing (‘stressors’).

The divide between average health and enhanced health is less distinct. Enhanced health is more than just being disease-free:it assumes high levels of physical strength, stamina and mental clarity, as well as physical beauty and maximal enjoyment and fulfilment from life. This requires the holistic integration of multiple factors that determine physical, psychological, emotional, social, economic, environmental and spiritual health. In many Eastern philosophies, the idea of enhanced health can be extended to the concept of ‘perfect health’ or ‘enlightenment’, whereby a person is ‘at one with the universe’ and hence in a state of perfect bliss or ‘nirvana’ (Cohen 2003).

Bliss, or ‘ananda’ in Sanskrit, is considered by Vedic scholars to be the innermost level of the individual self, as well as the nature of the whole universe. It is the goal of the path to enlightenment and is found in the deepest experience of meditation and the innermost level of our being (Maharishi 1957–64). Bliss is also the ultimate aim of Eastern healing and spiritual practices, which adopt a top-down approach by attempting to elicit bliss through meditation and other practices that enhance wellbeing (‘blissors’) (Cohen 2008a).

The state of bliss can also be considered as the ultimate in achieving human potential. As the late anthropologist Joseph Campbell states:

I think that most people are looking for an experience that connects them to the ecstasy of what it could feel like to be totally alive. To know the unburdened state of total aliveness is the pinnacle of the human potential. (Campbell 1988)

This ‘state of total aliveness’ is what many people may consider to be ‘wellness’.

THE WORLD IN CRISIS

It seems that all people at some time have tried to tackle the question of how to live well in the world. This single question has driven many different areas of human endeavour and has led to innovations that have created new technologies and ways of living that have allowed human populations to expand exponentially (Meadows et al 1976).

The disproportionate focus on illness has allowed unhealthy lifestyle practices to remain largely unchecked, thereby allowing them to expand across the globe to the point where they now represent the greatest threat to human health and survival. A 2005 report by the World Health Organization entitled Preventing chronic disease: A vital investment estimates that of the 58 million deaths in the world in 2005, 35 million (60%) were caused by chronic diseases such as heart disease, stroke, cancer, chronic respiratory diseases and diabetes. The report goes on to suggest that 80% of premature heart disease, stroke and type 2 diabetes and 40% of all cancers are preventable, concluding that the main modifiable risk factors for these diseases are lifestyle-related and include unhealthy diets, physical inactivity and tobacco use (WHO 2005).

It has been predicted that, as a result of unhealthy lifestyles, for the first time in history the lifespan of the next generation in the United States could be shorter than that of their parents (Olshansky et al 2005). In a PriceWaterhouseCoopers (PWC) report on the future of healthcare entitled HealthCast 2020: Creating a sustainable future (PWC 2005), it is suggested that ‘There is growing evidence that the current health systems of nations around the world will be unsustainable if unchanged over the next 15 years’ (PWC 2005, p 2), while ‘preventive care and disease management programs have untapped potential to enhance health status and reduce costs’ (PWC 2005, p 4).

IN SEARCH OF WELLNESS

The search for wellness is a common goal for all people. It can be understood as a conscious extension of the basic animal instinct to avoid pain that has its origins at the dawn of humanity when consciousness first became self-reflective (Cohen 2000). This search has influenced the evolution of medicine, which has seen the elaboration of two distinct yet complementary approaches: Eastern medicine, which is based on holistic thinking that maintains a cosmological and systems perspective outlining a philosophy of life; and Western medicine, which is based on a reductionist approach, emphasising controlled scientific experimentation and mathematical analysis (Cohen 2002).

The different health paradigms that aim to improve health and wellness have attempted to address the same issues in different ways. The principle of consilience suggests that there is an underlying unity of knowledge whereby a small number of natural laws may underpin seemingly different conceptual frameworks (Wilson 1999). Indeed there are general concepts and principles that seem to recur as themes across different healthcare paradigms.

THE THERMODYNAMICS OF WELLNESS

The concept of energy is described in different traditions as ‘life energy’, ‘vital force’, ‘prana’, ‘chi’ (or ‘Qi’), and is said to flow along defined pathways and support the functioning of living systems. Traditional Chinese medicine has developed a sophisticated framework for conceptualising this energy: it is seen to encompass the concept of ‘flow’ and to move according to the dynamic interplay of the opposite yet complementary forces of ‘yin’ and ‘yang’, which guide the process of transformation whereby non-living things become animate. In this view, pain and disease are said to result when the energetic flow is disrupted, and healing is aimed at restoring the natural balance and flow (Cohen 2002).

As science does not recognise a form of energy specific to living systems, many concepts underlying Eastern medicine have been criticised as unscientific. There are parallels, however, between Eastern and Western concepts, which can be seen to be linked through the concept of information. Information can be measured in terms of energy or ‘joules/degree Kelvin’ (Tribus & McIrvine 1971), and there is a congruence between the concepts of ‘Qi’ in Eastern medicine and ‘information’ in thermodynamics.

Thus the Eastern concept of disease arising from a blockage of ‘Qi’ can be seen to parallel the second law of thermodynamics, which describes a tendency towards disorder or entropy in an isolated system. Disease and the adverse effects of ageing, which include progressive degeneration of tissues together with loss of function, can therefore be related to an increase in entropy as a consequence of blockages or isolation of different systems. In contrast, the ability of living systems to grow, evolve and learn appears to defy the second law and can be related to an open exchange between organisms and the environment. This can be extended to the concept of ‘nirvana’, or perfect bliss, whereby a person is ‘at one with the universe’ and there is no distinction between self and non-self, thus creating an open system that is no longer prone to the increase in entropy that occurs in isolated systems (Cohen 2002).

WELLNESS AND FLOW

While it may be true that life depends on energy, living systems must remain ‘open’, as it is the flow of energy through them that maintains their integrity. The concept of ‘flow’ is a powerful one that provides a bridge between Eastern and Western thought. The concept of flow applies to both thermodynamic processes and systems theory, as well as to the cyclic thinking of Eastern medicine. The concept of flow has also been applied to subjective psychological states that involve the integrated functioning of mind and body. This concept has been developed by Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi who describes flow as ‘a joyous, self-forgetful involvement through concentration, which in turn is made possible by a discipline of the body’ (Csikszentmihalyi 1992).

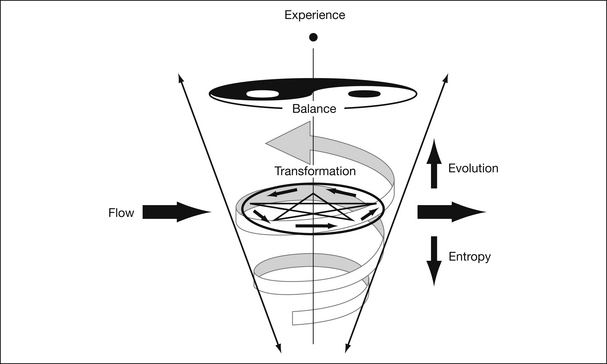

The idea that positive psychological states and wellbeing require ‘open systems’ is recognised in everyday common language in the phrases ‘having an open heart’ or ‘open mind’. The concept of flow sustaining life is also a basic tenet of Chinese and other traditional medicine philosophies. A thermodynamic model that includes the concept of energy and flow can also be seen to include many parallels between Eastern and Western concepts and thus provide links between different conceptual systems (Fig 12.2).

FIGURE 12.2 Pictorial conceptualisation of wellness concepts from traditional Chinese medicine (Cohen 2008a)

For example, the process of flow leading to transformation and the maintenance of living systems parallels the concept of the five elements or phases of transformation that is common to Chinese medicine, Ayurvedic medicine and ancient Greek medicine (which considered quintessence as a fifth element in addition to air, water, fire and earth). The result of this transformation is represented by the concept of ‘yin’ and ‘yang’, which refers to interdependent yet mutually exclusive opposites and can be compared to the concept of ‘complementarity’ in quantum physics or the concept of homeostatic balance in physiology. The result of this balance leads to an increase or decrease in order as described by entropy or evolution, while the infinite nature of direct experience can be compared to the concept of ‘Tao’ or the mathematical concept of ‘absolute infinity’, both of which are defined as being inherently incomprehensible (Cohen 2002).

WELLNESS METRICS

Wellness is holistic and multidimensional, and involves content and context. As such it is both subjective and objective, and is difficult to quantify. As yet there are no agreed upon metrics by which wellness can be reliably measured, despite the existence of many potential indicators and proxy measures that may be applied to populations as well as individuals. Thus it is now possible to measure subjective states such as ‘quality of life’, ‘happiness’ and ‘wellbeing’ through instruments such as the Australian Quality of Life Index (Cummins et al 2008), as well as to use more objective and physiological measures such as anthropometric and biometric data. Objective indicators of wellness can also be obtained from tissue sampling and measuring biochemical, hormonal, genetic, haematological and toxological data, as well as by testing functional capacity and performance. Further indicators for wellness can be obtained from demographic, socioeconomic and epidemiological data, which can be used to appraise access to food, shelter, education, employment, healthcare and consumer goods, as well as to rate health risks, ecological footprint, morbidity, mortality and life expectancy (Cohen 2008a).

The multidimensional nature of wellness makes any single measure inadequate, and so attempts have been made to combine measures from the different domains. For example, the BankWest Quality of Life Index tracks Australian living standards across municipalities based on key indicators of the labour market, the housing market, the environment, education and health (Bankwest 2008).

In attempting to measure ‘full spectrum wellness’, Travis and Ryan adopt the concept of a ‘wellness energy system’, which implies a thermodynamic model and measures wellness in terms of inputs and outputs. They acknowledge that ‘we are all energy transformers, connected with the whole universe’, and that ‘all our life processes, including illness, depend on how we manage energy’ (Travis & Ryan 2004). These authors further describe 12 aspects of wellness, which include inputs provided by breathing, eating, and sensing, and outputs described as self-responsibility and love, transcending, finding meaning, intimacy, communicating, playing and working, thinking, feeling and moving. These 12 aspects of wellness are the basis for the wellness inventory: evolved from health-risk appraisal techniques to become the first computerised wellness assessment tool, this inventory aims to provide a measure of wellness across the 12 dimensions through a self-reported questionnaire.

Perhaps the most comprehensive attempt to create a metric for wellbeing is the ‘Happy Planet Index’, which uses both subjective and objective data in an attempt to measure the ecological efficiency with which countries achieve long and happy lives for their citizens. The Happy Planet Index is a composite measure that is calculated by multiplying life satisfaction by life expectancy and then dividing by ecological footprint. It therefore takes a thermodynamic approach to the wellness of populations by dividing outputs (the length and happiness of human life) by inputs (natural resources) (Marks et al 2009). The finding that the average scores across nations are low, that all nations could do better and that no country does well on all three indicators or achieves an overall high score on the index has led the Happy Planet Index to be considered currently as the (Un)Happy Planet Index (Marks et al 2009).