CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION TO COMPLEMENTARY MEDICINE

WHAT IS COMPLEMENTARY MEDICINE?

The division of therapies into unorthodox or mainstream based on scientific merit is a little simplistic and open to subjective interpretation. For example, there are many practices that can be considered mainstream but are not necessarily scientifically proven, and many practices that can be considered ‘unorthodox’ but have scientific support. Furthermore, scientific evidence for a therapy may exist for only a specific clinical condition, or a therapy may be considered orthodox in one context, such as the use of vitamin supplements for treating a deficiency syndrome, but unorthodox in another, such as the use of vitamins in megadoses.

Overall, it is generally accepted that there are two broad classes of medicine, and terms such as ‘conventional’, ‘mainstream’, ‘orthodox’, ‘biomedicine’ and ‘scientific medicine’ are often contrasted with ‘unconventional’, ‘complementary’, ‘alternative’, ‘unorthodox’ and ‘fringe medicine’. Perhaps the most common distinction is between ‘conventional’ and ‘complementary’ therapies, yet these terms seem to defy precise definition. Even so, complementary medicine generally refers to the use of interventions that complement the use of drugs and surgery. The range of such therapies is vast and includes treatments based on traditional philosophies, manual techniques, medicinal systems, mind–body techniques and bioenergetic principles (Table 1.1). These techniques vary widely with respect to levels of efficacy, cost, safety and scientific validation, yet they often share common principles, including the concept of supporting the body’s homeostatic systems, as well as acknowledging the role of lifestyle practices, personal creativity, group sharing, the mind–body connection and the role of spiritual practice in health.

TABLE 1.1 The Range of Complementary Therapies

| Philosophical systems | Medicinal | Bioenergetic |

| Mind–body | Manual | |

COMPLEMENTARY MEDICINE IN AUSTRALIA

The practice of complementary medicine is flourishing in Australia. In 2000 it was estimated that about 50% of the Australian population took a ‘natural supplement’, about 20% formally saw a complementary medicine practitioner, and public spending on complementary medicines (A$2.3 billion in 2000) was more than four times patients’ contributions for all pharmaceutical medications (MacLennan 2002). A follow-up survey performed in 2004 found that although spending on complementary medicines had decreased to A$1.8 billion, there was a slight increase in the number of people taking natural supplements and visits to complementary medicine practitioners rose to 26.5% (MacLennan et al 2006). More recent statistics reveal that up to 70% of the Australian population has used complementary medicine in a number of different forms (Xue et al 2007). Data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics indicates that in the 10 years leading up to 2006, the number of people visiting CM practitioners within a 2 week period rose from approximately 500,000 to 750,000 and over the same period there was an 80% increase in the number of people employed as a CM practitioner. The most commonly consulted CM practitioners were chiropractors, naturopaths and acupuncturists (Censuses of Population and Housing and from the ABS 2004-05 National Health Survey).

These figures are comparable to those from the USA, which further suggest that the use of CAM is increasing. Between 1990 and 1997 expenditure on these therapies in the USA increased by 45.2%, with the total of more than US$21 billion exceeding out-of-pocket expenditures for all US hospitalisations. Furthermore, visits to CAM practitioners exceeded total visits to all US primary-care physicians (Eisenberg 1998).

Similarly, use of complementary therapies by general practitioners seems to be increasing. Recent surveys have estimated that 30–40% of Australian GPs practise a complementary therapy and more than 75% formally refer their patients for such therapies (Cohen et al 2005, Hall 2000, Pirotta 2000). It is also estimated that more than 80% of GPs think it appropriate to practise therapies such as hypnosis, meditation and acupuncture and that most GPs desire further training in various complementary therapies (Cohen et al 2005, Pirotta 2000).

Interestingly a recent survey of Australian GPs found that, based on their opinions, complementary therapies could be classified as follows: non-medicinal and non-manipulative therapies such as acupuncture, massage, meditation, yoga and hypnosis, which GPs considered to be highly effective and safe; medicinal and manipulative therapies, including chiropractic, Chinese herbal medicine, osteopathy, herbal medicine, vitamin and mineral therapy, naturopathy and homeopathy, which more GPs considered potentially harmful than potentially effective; and esoteric therapies such as spiritual healing, aromatherapy and reflexology, which were seen to be relatively safe yet also relatively ineffective. Furthermore, according to GPs the risks of complementary therapies were seen to arise mainly from incorrect, inadequate or delayed diagnoses and interactions between complementary medications and pharmaceuticals, rather than the specific risks of the therapies themselves (Cohen et al 2005).

Despite moves to support complementary therapies, in practice it seems that there are two distinct healthcare systems operating in parallel, and interaction is still in its infancy. It is estimated that, of the patients who go to complementary practitioners, more than 57% do not inform their doctor they are doing so (MacLennan et al 2006). This lack of communication is potentially hazardous, as it raises the possibility of treatment interactions; this is even more significant when it is considered that in the USA more than 80% of people seeking complementary treatment for ‘serious medical conditions’ were found to be receiving treatment from a medical doctor for the same condition (Eisenberg 1993).

COMPLEMENTARY MEDICINE IN NEW ZEALAND

Complementary medicine has been practised in New Zealand since the 19th century (Duke 2005). In 1908, the Quackery Prevention Act was enacted to prevent the sale of dubious medicines or medical devices and represents an early attempt to regulate the practice of CAM. At the time, what is now termed CAM had achieved a level of acceptance among the medical profession; however, a division began to emerge between medical and complementary practices because of the Act.

Over the past decade, studies indicate that conventional medical practitioners in New Zealand practise some form of complementary therapy or refer their patients to complementary medicine practitioners (Duke 2005). One study of 226 GPs in Wellington suggested that they saw their role as ranging from comprehensive provider of both conventional and complementary medicine to selective practitioner of some options (Hadley 1988). Of these GPs, 24% had received complementary medicine training, 54% wanted further training in a complementary therapy, and 27% currently practised at least one therapy. The study also found that acupuncture, hypnosis and chiropractic were the most popular therapies among this group.

THE MEDICAL SPECTRUM

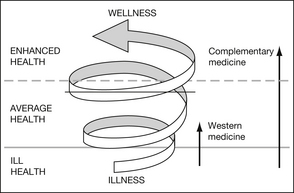

Health and disease can also be considered to inhabit opposite ends of an illness–wellness spectrum, with health being classified into three broad areas — ill-health, average health and enhanced health (Figure 1.1) (see also Chapter 12). In the past, Western medicine has focused on helping people move from ill-health to average health and has viewed the absence of disease as an ideal goal. In relatively recent times, preventative treatment has also been incorporated into medical management, in an attempt to reduce the incidence or exacerbation of disease states. In comparison, CAM has always maintained a focus on preventative approaches and moving people from average health to a state of enhanced health. In Eastern medicine there is a concept of a ‘perfect health’ state, in which a person is totally balanced and ‘at one with the universe’, and hence in a state of perpetual bliss or ‘nirvana’.

INTEGRATIVE AND HOLISTIC MEDICINE

When complementary and conventional approaches to medicine are combined, their practice is often called holistic or integrative medicine (see Chapter 6). This combined approach aims to achieve a balance between art and science, theory and practice, mind and body, and prevention and cure. The practice of integrative medicine is highly individualised and focuses on how medicine is practised rather than the use of any particular modalities. It embraces a philosophy that adheres to certain principles, such as the BEECH principles:

| B | Balance between complementary aspects |

| E | Empowerment and self-healing |

| E | Evidence-based care supporting the concept ‘First, do no harm’ |

| C | Collaboration between practitioner and patient, and between different practitioners |

| H | Holism and the recognition that health is multidimensional. |

| S | Stress management |

| E | Exercise |

| N | Nutrition |

| S | Social and spiritual interaction |

| E | Education |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree