Introduction to Basic Pharmacology and Other Common Therapies

Learning Objectives

After studying this chapter, the student is expected to:

1. Define common terms used in pharmacology.

2. Differentiate the types of adverse reactions.

3. Explain the factors that determine blood levels of a drug.

4. Compare the methods of drug administration.

5. Describe the role of receptor sites in drug action.

6. Differentiate a generic name from a trade name.

8. Describe the roles of specified members of the health care team, traditional and alternative.

Key Terms

acupoints

antagonism

compliance

holistic

idiosyncratic

meridians

parenteral

placebo

potentiation

synergism

synthesized

Pharmacology

Health professionals are required to record and maintain medical profiles for each patient including all medications, including over-the-counter drugs. An example of a general/simple medical history can be found in Ready Reference 6 at the back of the book. This chapter provides a brief overview of the basic principles of pharmacology and therapeutics.

Basic Principles

Pharmacology is an integrated medical science involving chemistry, biochemistry, anatomy, physiology, microbiology, and others. Pharmacology is the study of drugs, their actions, dosage, therapeutic uses (indications), and adverse effects. Drug therapy is directly linked to the pathophysiology of a particular disease. It is helpful for students to understand the common terminology and concepts used in drug therapy to enable them to look up and comprehend information on a specific drug. Medications frequently have an impact on patient care and have a part in emergency situations/care. It is important to recognize the difference between expected manifestations of a disease and the effects of a drug.

Drugs may come from natural sources such as plants, animals, and microorganisms such as fungi, or they may be synthesized. Many manufactured drugs originated as plant or animal substances. In time the active ingredient was isolated and refined in a laboratory and finally mass produced as a specific synthesized chemical or biologic compound.

A drug is a substance that alters biologic activity in a person. Drugs may be prescribed for many reasons, some of which are:

• To promote healing (e.g., an anti-inflammatory glucocorticoid)

• To cure disease (e.g., an antibacterial drug)

• To control or slow progress of a disease (e.g., cancer chemotherapy)

• To prevent disease (e.g., a vaccine)

• To decrease the risk of complications (e.g., an anticoagulant)

• To increase comfort levels (e.g., an analgesic for pain)

• As replacement therapy (e.g., insulin)

• To reduce excessive activity in the body (e.g., a sedative or antianxiety drug)

Pharmacology is organized into separate disciplines that deal with actions of drugs.

• Drug-induced responses of physiologic and biochemical systems in health and disease

• Drug amounts at different sites after administration

• Choice and drug application for disease prevention, treatment, or diagnosis

• Pharmacy

• The preparation, compounding, dispensing, and record keeping of therapeutic drugs

Drug Effects

A drug may exert its therapeutic or desired action by stimulating or inhibiting cell function. Some drugs, such as antihistamines, block the effects of biochemical agents (like histamine) in the tissues. Other drugs have a physical or mechanical action; for example, some laxatives that provide bulk and increase movement through the gut. Drugs are classified or grouped by their primary pharmacologic action and effect, such as antimicrobial or anti-inflammatory. The indications listed for a specific drug in a drug manual provide the approved uses or diseases for which the drug has been proved effective. Off-label uses are those for which the drug has shown some effectiveness, but not the use for which the drug was approved by regulatory bodies. Listed contraindications are circumstances under which the drug usually should not be taken.

Generally drugs possess more than one effect on the body, some of which are undesirable, even at recommended doses. If these unwanted actions are mild, they are termed side effects. For example, antihistamines frequently lead to a dry mouth and drowsiness, but these effects are tolerated because the drug reduces the allergic response. On occasion, a side effect is used as the primary goal; for example, promethazine (Phenergan) has been used as an antiemetic or a sedative as well as an antihistamine. When the additional effects are dangerous, cause tissue damage, or are life threatening (e.g., excessive bleeding), they are called adverse or toxic effects. In such cases, the drug is discontinued or a lower dose ordered. In some cases, such as cancer chemotherapy, a choice about the benefits compared with the risks of the recommended treatment is necessary. Unfortunately, a long period of time may elapse before sufficient reports of toxic effects are compiled to warrant warnings about a specific drug, and in some cases its withdrawal from the marketplace. It is important to realize that undesirable and toxic effects can occur with over-the-counter (OTC) items as well as prescription drugs. For example, megadoses of some vitamins are very toxic, and excessive amounts of acetaminophen can cause kidney and liver damage. In late 2000, some cough and cold preparations as well as appetite suppressants containing phenylpropanolamine (PPA) were removed from the market because of a risk of hemorrhagic strokes in young women. Research continues into the development of “ideal” drugs with improved or more selective therapeutic effect, fewer (or no) side effects, and no toxic effects.

Several specific forms of adverse effects should be noted:

• Teratogenic or harmful effects on the fetus, leading to developmental defects, have been associated with some drugs. Fetal cells are particularly vulnerable in the first 3 months (see discussion of congenital defects in Chapter 21). This is an area in which research cannot be totally effective in screening drugs. It is recommended that pregnant women or those planning pregnancy avoid all medications.

The effect of the combination may be increased much more than expected (synergism) or greatly decreased (antagonism). Synergistic action can be life threatening; for example, causing hemorrhage or coma. It has been documented that the majority of drug overdose cases and fatalities in hospital emergency departments result from drug-drug or drug-alcohol combinations.

Alternatively, when synergism is established, it may be used beneficially to reduce the dose of each drug to achieve the same or more beneficial effects with reduced side effects. For example, this is an intentional advantageous action when combining drugs to treat pain.

The presence of an antagonist prevents the patient from receiving the beneficial action of a drug. In a patient with heart disease or a serious infection, this would be hazardous. On the other hand, antagonistic action is effectively used when an antidote is required for an accidental poisoning or overdose.

One other form of interaction involves potentiation, whereby one drug enhances the effect of a second drug. For example, the inclusion of epinephrine with local anesthetics is intended to prolong the effects of the local anesthetic, without increasing the dose. It causes vasoconstriction in the area, which decreases blood flow and thereby helps keep the anesthetic in the area longer because it will not be absorbed as quickly.

Administration and Distribution of Drugs

The first consideration with administration is the dosage of the medication. The dose of a drug is the amount of drug required to produce the specific desired effect in an adult, usually expressed by a weight or measure and a time factor such as twice a day. A child’s dose is best calculated using the child’s weight, not age. A proper measuring device should be used when giving medication because general household spoons and cups vary considerably in size.

In some circumstances, a larger dose may be administered initially, or the first dose may be given by injection, to achieve effective drug levels quickly. This “loading dose” principle is frequently applied to antimicrobial drugs, in which case it is desirable to have sufficient drug in the body to begin destruction of the infecting microbes as soon as possible. It is equally important not to increase the prescribed dose over a period of time (the “if one tablet is good, two or three are better” concept), nor to increase the frequency, because these changes could result in toxic blood levels of the drug.

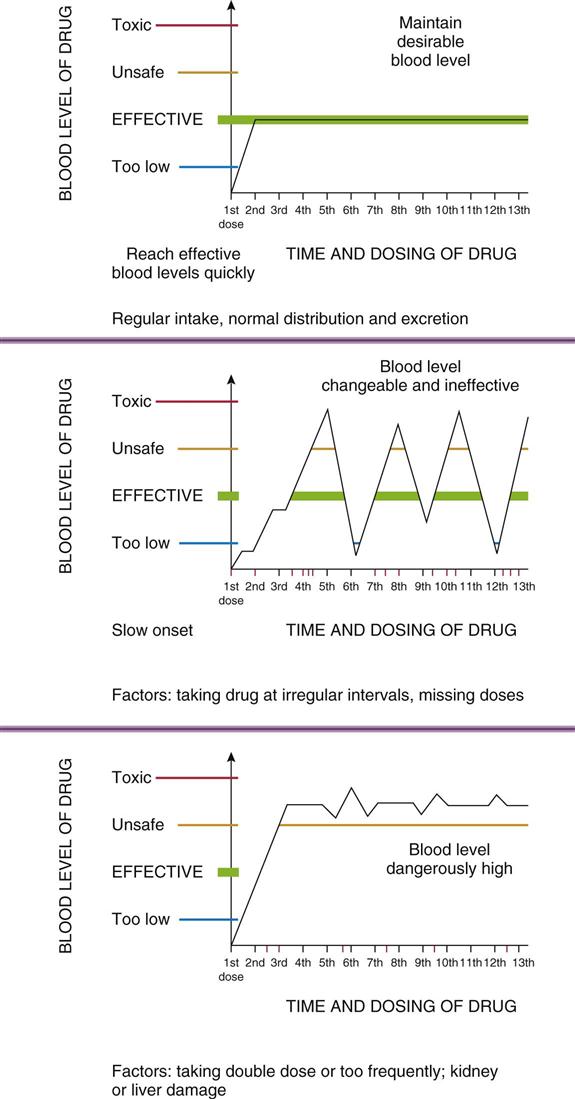

The frequency of dosing is important in maintaining effective blood levels of the drug without toxicity, and directions regarding timing should be carefully followed (Fig. 3-1). Optimum dosing schedules are established for each drug based on factors such as absorption, transport in the blood, half-life of the particular drug, and biotransformation. Drugs usually should be taken at regular intervals over the 24-hour day, such as every 6 hours. Directions regarding timing related to meals or other daily events are intentional and should be observed. For example, insulin intake must match food intake. Sometimes the drug is intended to assist with food intake and digestion and hence should be taken before meals. In other cases, food may inactivate some of the drug or interfere with absorption, reducing the amount reaching the blood; therefore the drug must be taken well before a meal or certain foods must be avoided. Alternatively, it may be best to take the drug with or after the meal to prevent gastric irritation. A sleep-inducing drug is more effective if taken a half-hour before going to bed, rather than when getting into bed with the expectation that one will fall asleep immediately.

Actual blood levels of a drug are also dependent on such factors as the individual’s:

• Circulation and cardiovascular function

• Age

• Body weight and proportion of fatty tissue

• Ability to absorb, metabolize, and excrete drugs (liver and kidney function)

Therefore drug dosage and administration may have to be modified for some individuals, particularly young children and elderly people. It is sometimes difficult to determine exactly how much drug actually is effective at the site. A laboratory analysis can determine actual blood levels for many drugs. This may be requested if toxicity is suspected.

A drug enters the body by a chosen route, travels in the blood around the body, and eventually arrives at the site of action (e.g., the heart), exerts its effect, and then is metabolized and excreted from the body. For example, a drug taken orally is broken down and absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract into the blood (rather like ingesting food and drink!). Sometimes a drug is administered directly into an organ or tissue where it is expected to act. Another exception is the application of creams on skin lesions, where minimal absorption is expected.

Drugs can be administered for acting locally or having a systemic action:

The major routes for administration of drugs are oral and parenteral (injection). Table 3-1 provides a comparison of some common routes, with regard to convenience, approximate time required to reach the blood and the site of action, and the amount of drug lost. The common abbreviations for various routes may be found in Ready Reference 4. Drugs may also be administered by inhalation into the lungs (either for local effect, e.g., a bronchodilator, or for absorption into blood, e.g., an anesthetic), topical application through the skin or mucous membranes, and rectally, using a suppository for local effect or absorption into the blood. The transdermal (patch) method provides for long-term continuous absorption of drugs such as nicotine, hormones, or nitroglycerin through the skin into the blood. Variations on these methods are possible, particularly for oral medications. Time-release or long-acting forms are available (e.g., for cough and cold medications), which may contain three doses to be released over a 12-hour period. Less frequent administration may be more efficient and increase patient compliance (adherence to directions) because of the convenience. Enteric-coated tablets (a special coating that prevents breakdown until the tablet is in the intestine) are prepared for drugs such as aspirin to prevent gastric ulcers or bleeding in persons who take large doses of this anti-inflammatory drug over prolonged periods of time.

TABLE 3-1

Various Routes for Drug Administration

| Route | Characteristics | Time to Onset and Drug Loss | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Oral tablet, capsule, liquid ingested | Simple administration, easily portable | Long time to onset, e.g., 30-60 min More loss in digestive system | Tablets stable, cost varies, safe | Taste and swallowing problems; gastric irritation; uncertain absorption |

| Sublingual (e.g., nitroglycerin) | Very simple to use, portable | Immediate, directly into blood, little loss of drug | Convenient, rapid action | Tablets soft and unstable |

| Subcutaneous Injection (e.g., insulin) | Requires syringe, self-administer, portable | Slow absorption into blood Some loss of drug | Simplest injection Only small doses can be given | Requires asepsis and equipment Can be irritating |

| Intramuscular Injection (e.g., penicillin) | Requires syringe and technique (deltoid or gluteal muscle) | Good absorption into blood Some time lag and drug loss until absorption | Use when patient unconscious or nauseated Rapid, prolonged effect | Requires asepsis and equipment Short shelf-life Discomfort, especially for elderly |

| Intravenous Injection | Requires equipment and technique (directly into vein) | Immediate onset and no drug loss | Immediate effect, predictable drug level Use when patient unconscious | Costly, skill required No recovery of drug Irritation at site |

| Inhalation (into respiratory tract) | Portable inhaler (puffer) or machine and technique required | Rapid onset, little loss of drug. | Local effect or absorb into alveolar capillaries Rapid effect Good for anesthesia | Requires effective technique |

| Topical (skin or mucous membranes) gel, cream, ointment, patch, spray, liquid, or suppository | Local application, portable Also eye, ear, vaginal, rectal application | Onset rapid Some loss Absorption varies | Easy to apply Few systemic effects Useful local anesthetic | Can be messy Sometimes difficult application, e.g., eye |

| Intraperitoneal pump | Requires surgery | Excellent control of blood glucose levels | Immediate onset | Costly and may become infected |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree