INTRODUCTION

Sarcomas of bone and soft tissue are extremely diverse. To date, there are almost 100 different types of soft tissue neoplasms that have been described and incorporated into the World Health Organization (WHO) scheme of tumor classification. Many of these lesions represent exceedingly rare entities that have only been recently described or documented, often by large referral centers. Alternatively, many of these lesions are so common (lipomas, superficial fibromatoses) as to be easily overlooked or dismissed as lesions of no consequence.

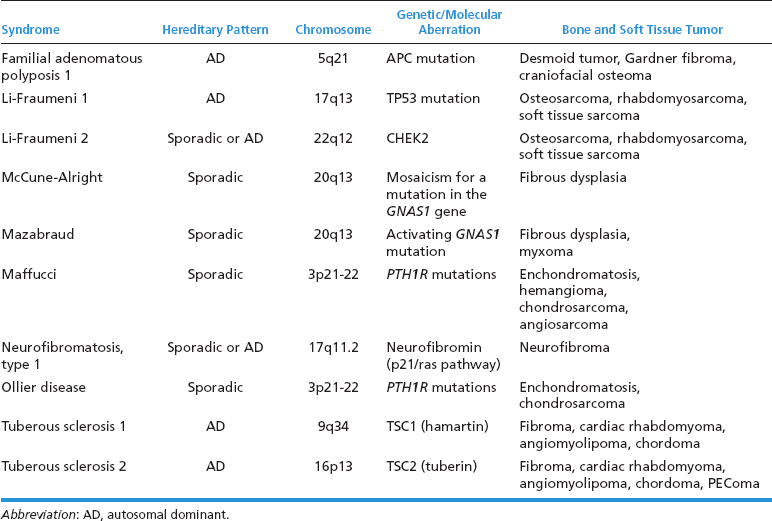

The etiology of sarcoma is unknown. There are clearly some features that place an individual at an increased risk of developing sarcoma. These include radiation exposure as well as some specific oncogenic viral infections and immunodeficient states. In addition, there are some particularly vulnerable individuals, those with either inherited or acquired genetic defects (Table 1.1.1).

CLASSIFICATION AND NOMENCLATURE

The systemic classification of sarcomas into diagnostically recognizable different subtypes began in the early part of the 20th century. The original classification schemes were based on the presumed tissue of origin of the sarcoma or the type of histologic differentiation. Hence the use of the terms ‘liposarcoma” for lesions of adipocytic origin and the terms “leiomyosarcoma” and “rhabdomyosarcoma” to signify origin from smooth and striated muscle, respectively. Minor alterations to the classification paradigm were made with the widespread adoption of immunohistochemical techniques. In addition, there have been some changes in classification based on current molecular and cytogenetic information. No doubt, the “traditional” scheme will continue to evolve as more information becomes available. The current iteration of the traditional classification scheme is outlined in Table 1.1.2.

The traditional classification system remains largely intact and persists as the primary means of identifying and subclassifying lesions of soft tissue and bone. Although this system remains the acknowledged standard, it is not without some shortcomings. For instance, there are a large number of entities for which origin is still unclear at this point. The latter would include an assortment of neoplasms such as clear cell sarcoma, alveolar soft part sarcoma, and angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma. Under the current scheme, these diverse neoplasms are simply lumped into an “other” category. In addition, many of the high-grade pleomorphic sarcomas (pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma, liposarcomas, etc.) resemble each other more than their namesake tissues of origin. And it goes without saying that there are still many true misnomers that have unfortunately been codified into the current classification and nomenclature scheme. One of the most obvious of these is synovial sarcoma.

As diagnosis of mesenchymal tumors has moved from an open biopsy to a smaller biopsy type (either cutting needle core or fine needle biopsy), there has been a parallel evolution of an alternative classification scheme. The so-called “pattern-based” approach was first largely used by aspiration cytopathologists in attempts to classify neoplasms based on the most prevalent morphologic feature. As such, categories such as “spindle cell” or “myxoid” or “epithelioid” terms emerged. This type of classification system represented a practical attempt to define the tumor type on the most minimal of characteristics. Early proponents of the cytologic descriptions and characterization of bone and soft tissue neoplasms were quick to broaden the pattern recognition approach and legitimize its use in the diagnostic setting. Current defined categories for lesions of soft tissue include tumors with adipose stroma, myxoid lesions, spindle cell lesions, small round blue cell tumors, pleomorphic tumors, and others (Figures 1.1.1–1.1.6). Similar categories exist for a “pattern-based” approach to the diagnosis of bone tumors, but these categories tend to be based on the predominant stromal feature (osteoid vs. cartilage) and as such, extensively overlap the traditional classification scheme (Figures 1.1.7–1.1.12). This approach has also been adopted by surgical pathologists who find that when working with small core biopsies, this type of alternative classification model can be extremely useful.

The pattern-based approach, although very practical, is not without problems either. Many neoplasms, again synovial sarcoma is just one, do not fit neatly into any given pattern as they often are both “spindled” and “epithelioid” at the same time. Likewise, many lesions, plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumors, for instance, have architectural features that define the lesion, but do not fit easily into any one of the simplistic categories. And lastly, categorization of lesions by a pattern-based approach will break up many classes of related tumors that may be best compared to one another. The different subtypes of liposarcoma, for example, all have recognizable lipogenic differentiation, but will be subcategorized into “spindled” or “myxoid” or “pleomorphic” categories under a pure pattern recognition approach.

Recognizing the relative merits and faults of each of these two major classification strategies, the authors of this atlas have elected not to be purists, but to present this material in a “hybrid” format with an emphasis on pattern recognition (Table 1.1.3). Thus, adipocytic, osseous, and cartilaginous tumors remain largely intact as groups instead of split into various categories. But the broad categories of “myxoid,” “small round blue cell tumors,” and “spindled tumors” are presented under a pattern-based approach.

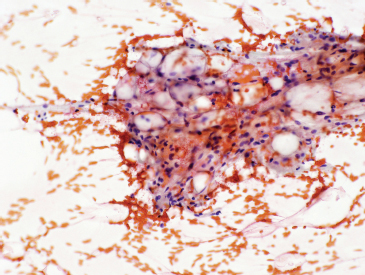

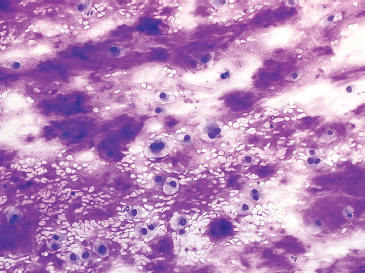

FIGURE 1.1.1 Adipose tissue is easily recognized in aspirates and small biopsy specimens.

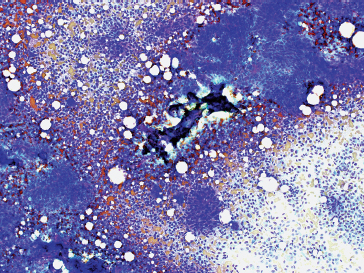

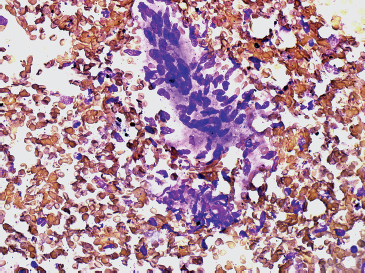

FIGURE 1.1.2 Extracellular matrix material is a unifying characteristic of a large group of soft tissue lesions.

FIGURE 1.1.3 Spindle cell lesions are another major category of soft tissue tumors in a pattern-based paradigm.

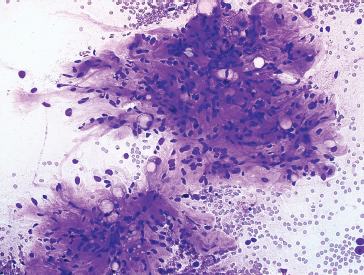

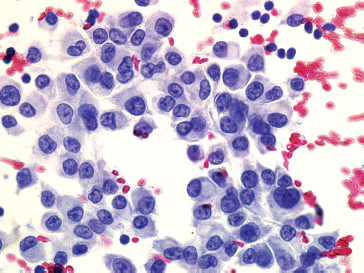

FIGURE 1.1.4 There are numerous epithelioid soft tissue lesions that can mimic both melanoma and poorly differentiated carcinoma.

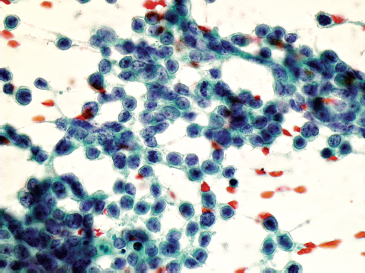

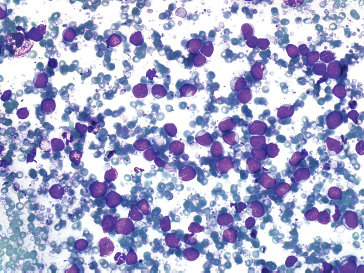

FIGURE 1.1.5 Small round blue cell tumors are a diagnostic challenge on both traditional biopsy samples and needle aspiration.

FIGURE 1.1.6 Pleomorphic forms of sarcoma are characterized by marked diversity in cell size and shape.

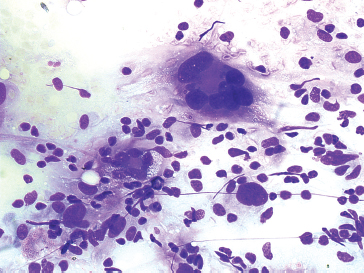

FIGURE 1.1.7 A fragment of osteoid in an aspiration of an osteosarcoma.

FIGURE 1.1.8 Cartilaginous lesions are characterized by abundant extracellular matrix material.

FIGURE 1.1.9 Small round blue cell tumors are also a major diagnostic category for osseous-based lesions.

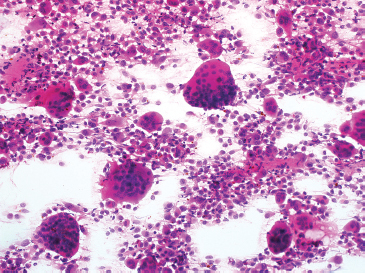

FIGURE 1.1.10 Giant cell-rich lesions of bone are often immediately recognizable because of the number of giant cells.

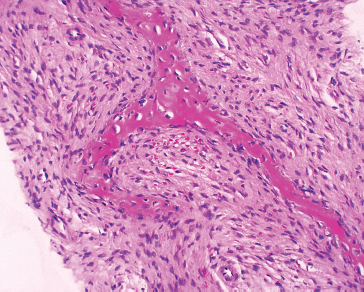

FIGURE 1.1.11 Spindle cell lesions of bone can be diagnostically challenging. This example of fibrous dysplasia was identified on a core needle biopsy.

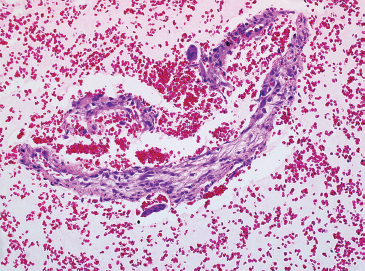

FIGURE 1.1.12 Cystic lesions of bone are often difficult to diagnose by small biopsy specimens. In this example, a cell block prepared from an aspirate of an aneurysmal bone cyst contained fragments of the cyst wall.

TABLE 1.1.2 Traditional Classification of Tumors of Primary Soft Tissue and Bone Lesions

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree