International Organization and Management

A few megacompanies with broad international presence will be supported by a host of small companies that are scientifically and technically highly specialized. It is argued that this scenario will develop at the expense of the national and international companies with only limited representation in the major markets and with only limited access to scientific excellence.

–Jurgen Drews. From On International Development.

The primary question in global drug development is not whether or not a multinational pharmaceutical company should develop drugs internationally, but on what scale it should be done and how it may best be done. Virtually every major multinational company has moved into the era of developing drugs on an international scale. If the company intends to market its drugs worldwide, then it will develop drugs on a “global” basis. However, if it wishes to focus on a number of countries or areas, then its drug development is better described as “international.” This sharp distinction is not always made in this book. The issues discussed focus mainly on technical details and strategies that enable companies to develop drugs most effectively. Strategies are developed that reflect the company, its organizational structures, disease areas of interest, and the geographical areas targeted for marketing.

The major goal of global drug development is to have a drug reach the market as soon as possible in all targeted countries. Other goals include achieving a financially stronger company, better staff morale, and more efficient drug development.

MODELS OF INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AND COORDINATION BETWEEN TWO DRUG DEVELOPMENT SITES WITHIN A MULTINATIONAL COMPANY

International cooperation in drug development between two or more sites may exist on multiple levels. Three models are described. The first model is loose cooperation with a sharing of results and

information on the status of each site’s activities. Nonetheless, each site pursues drug development in a generally independent manner. The second model involves all relevant sites pursuing work jointly on drug development, after a drug reaches a certain point in the development process. This point may be at the initiation of Phase 1 or 2 trials or after drug efficacy is demonstrated by one of the sites. This model keeps drug ownership at the site where work was initiated. The third model involves all relevant sites jointly developing a drug from the time when a project is initiated. This leads to joint ownership of all drug projects. It may be desirable for a company to initiate work on only those projects that receive international agreement at the outset. The particular model of drug development chosen should be the one that is believed to be best able to achieve the company’s goals. Two or more models may be used by a single company, with the choice dependent on the nature of the drug or its intended markets. Chapter 18 discusses this topic in much greater detail.

information on the status of each site’s activities. Nonetheless, each site pursues drug development in a generally independent manner. The second model involves all relevant sites pursuing work jointly on drug development, after a drug reaches a certain point in the development process. This point may be at the initiation of Phase 1 or 2 trials or after drug efficacy is demonstrated by one of the sites. This model keeps drug ownership at the site where work was initiated. The third model involves all relevant sites jointly developing a drug from the time when a project is initiated. This leads to joint ownership of all drug projects. It may be desirable for a company to initiate work on only those projects that receive international agreement at the outset. The particular model of drug development chosen should be the one that is believed to be best able to achieve the company’s goals. Two or more models may be used by a single company, with the choice dependent on the nature of the drug or its intended markets. Chapter 18 discusses this topic in much greater detail.

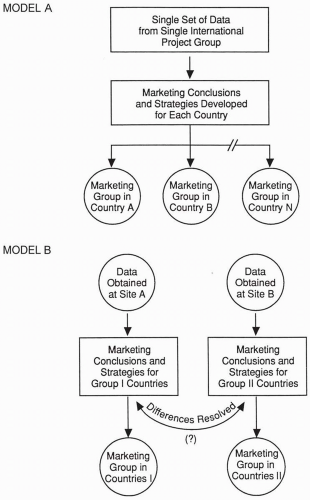

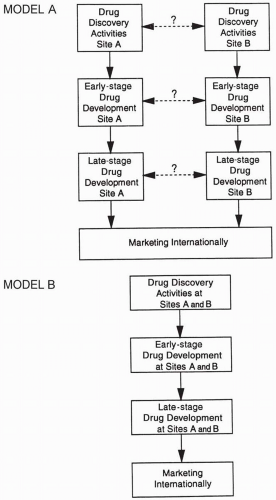

A certain number of clinical trials function as the core of most, if not all, regulatory submissions. Implementing and running a global drug development system vary greatly from company to company, depending on a firm’s experience, goals, and traditions and the number, nature, and location of subsidiaries. Some companies with centralized organizations have relatively complete international drug development systems and a single clinical plan for international use. A global tracking system is used to monitor numbers of patients enrolled at each site and to track whether target dates are being met for each of the trial’s milestones (e.g., initiation, completion, report writing) or for various regulatory activities. Models presented in Figs. 47.1 and 47.2 illustrate that the methods used to obtain data may influence a product’s marketing.

PLANNING AN INTERNATIONAL CLINICAL PROGRAM

Planning an international clinical program for a single drug requires from several months to a full year from project initiation to ensure that important points are not missed. This period should be taking place while preclinical and technical studies are underway. This clinical plan cannot be rushed, or the resultant program may create problems and questions that may lead the entire drug’s development into serious difficulties.

It is important to review the clinical program with more than a single consultant in each country. These experts in academia, industry, and/or relevant government agencies should be consulted as to the feasibility of implementing the plan. The experts should be asked whether the proposed clinical program is appropriately tailored to the needs and nature of the medical practice of their country and is possible to carry out successfully in the proposed time frame. Situations will arise where a special program must be created within one or more countries that must opt out of the global development scheme. Traditionally, Japan has been viewed as a country that requires special considerations.

IN WHICH COUNTRIES SHOULD CLINICAL TRIALS BE CONDUCTED?

Although many factors enter this discussion, only a few will be mentioned. It is usually easiest to evaluate initially a drug in the United States if its preclinical development took place there. Although regulatory requirements to initiate human tests are generally more involved in the United States than in most other countries, this distinction is gradually disappearing in regard to Europe. This is resulting from Europeans adopting more standard requirements to initiate a “first in man” study. Moreover, a company usually achieves reliable data in the United States and avoids what is often a time-consuming effort in exporting the drugs. Investors also like to know that the company has been able to obtain an Investigational New Drug Application in the United States. Drugs developed in other countries, however, are seldom sent to the United States for their initial testing, but this appears to be a growing trend, or at least there is a trend to obtain a US Investigational New Drug Application even if the first trial is conducted outside the United States (usually for economic reasons). Testing new compounds in underdeveloped countries is not usually a good idea because of the (usual) lack of high-quality facilities, investigators, and background experience of the staff. Data that result from such studies are usually not reliable and also are not generally accepted by regulatory agencies as valid. Poor information is much worse than having no information because it can easily send the company on a wild goose chase trying to answer questions that did not need to be raised. This effort may last several years and cost many millions of dollars, pounds, or euros.

Later in drug development, foreign locations are frequently used (a) to complete core trials in countries where data will then be acceptable to their regulatory authorities, (b) to adhere to various countries’ regulatory requirements, (c) for promotional studies, (d) to enlist help from local opinion leaders, or for other reasons. In choosing the countries in which to conduct trials, it may be relevant to consider whether there is a national death registry to assist in long-term patient follow-up and also to determine the stability of the patient population remaining at or near the sites of the study.

Local clinical trials are often requested (or even required) by some regulatory authorities, rather than approving a drug based entirely on foreign data. There are various reasons for this request. For example, most patients in the country may differ from those in whom the trials were conducted in terms of diet, weight, and ethnic factors. Medical practice may differ in the ways that patients are treated. If so, then at least one trial should be conducted under the conditions in which the drug will be sold. The regulatory authority may not be readily able to audit the investigator’s sites if they are in a different country. Finally, there is what may be the major reason in many cases—chauvinism. In fact, the author was told by the head of a nontropical Asian country’s Food and Drug Administration (FDA) that they insisted on trials being done in their country as “bridging” trials because the climate was different from that in Europe and the United States.

DIFFERENT METHODS TO ASSIGN PATIENT QUOTAS AMONG COUNTRIES

When a multinational study is being designed, there are several factors relating to the number of patients to enroll in each of the countries that is included in the trial. A few considerations include cultural differences, practice of medicine, resources, availability of patients and investigators, availability of adequate facilities, and ability to obtain a minimal number of patients so that the

data are not statistically biased in favor of one country. As a result, there are often patient quotas assigned to each country that participates in a multinational trial.

data are not statistically biased in favor of one country. As a result, there are often patient quotas assigned to each country that participates in a multinational trial.

Figure 47.1 Two models for marketing groups to consider in obtaining the data they need to market their drugs. Various hybrids and variations are possible. |

One approach to enrolling patients in three (or more) countries (assuming one site per country) is to enter patients as rapidly as possible at all sites until the total quota for the entire trial is achieved. A different approach is to assign a certain quota for each site based on predetermined statistical and practical considerations. In this approach, each site continues to enroll patients until it achieves its own specific goal. The potential problem with the latter approach is that one or more sites may complete enrollment much earlier than other sites and not be allowed to enroll additional patients. This could lead to a marked delay in completing the overall trial and in registering the drug. The best

solution is to establish a minimum number of patients for each site (determined by the trial statisticians) to enroll and then to allow sites to enroll a larger number if it is possible for them to do so. An upper limit may also be determined for each site.

solution is to establish a minimum number of patients for each site (determined by the trial statisticians) to enroll and then to allow sites to enroll a larger number if it is possible for them to do so. An upper limit may also be determined for each site.

Figure 47.2 Two models of drug discovery and development that provide data needed by marketing. The question marks and dotted lines in Model A indicate that interactions between the groups shown are possible but not required.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|